“See that kid over there? That’s my 12-year-old nephew from Staten Island. You couldn’t get more white and suburban than him. But Dre’s record is all the kid listens to. When you sell this many albums, they are not all going to the South Bronx.” —Jimmy Iovine, Rolling Stone, 1993

Do you remember the first album you bought?

As a 10-year-old living in North Providence, Rhode Island, in the pre-file-sharing, pre-streaming days of the early ’90s, I would tape songs off the radio onto blank cassettes, trying to hit record at the right moment and stop just before DJ banter ruined a perfect compilation. I distinctly remember having a 120-minute Memorex that had Dr. Dre’s “Dre Day” on the A-side no fewer than a half-dozen times.

But at some point in the summer of 1993, six or so months after The Chronic came out, I decided I was sick of these self-recorded cassettes—I wanted the real thing. I begged my mother to take me to the nearby Strawberries, a local record store chain that reportedly had mob ties, and used the money I’d earned from (poorly) mowing the lawn to make my first album purchase. But I had to wait to listen. That night, we had dinner with my aunt, who said I could put my new tape in her deck—so long as there wouldn’t be too much cursing. I assured her there wouldn’t be; I had listened to a handful of these obscenity-free songs on the radio literally hundreds of times. So I ripped off the packaging, quickly admired that new-cassette smell, and hit Play.

Of course, these were the first words we heard:

It would seem no one told me that “Dre Day” becomes “Fuck Wit Dre Day” when you don’t have to worry about FCC violations.

The Chronic, which is finally available on all major music streaming platforms as of Monday (4/20, of course), was the rap album that conquered the suburbs and codified the dominant sound of an entire coast. It made the former N.W.A producer a household name and a larger-than-life myth while launching the stratospheric career of a lanky, unknown MC named Snoop Dogg. The Chronic also sparked debates over misogyny and homophobia in rap music and served as the first step in Dre’s attempts to rewrite a troubling personal history that includes several high-profile incidents of violence against women. But at the time, I didn’t know any of that. I just knew that I was hearing something unlike anything I had heard before.

“I needed a record to come out. I was broke. I didn’t receive one fuckin’ quarter in the year of ’92, because Ruthless spent the year trying to figure out ways not to pay me so that I’d come back on my hands and knees. If I had to go back home living with my mom, that wasn’t going to happen.” —Dr. Dre, Rolling Stone, 1993

Born Andre Romelle Young in Compton, California, Dr. Dre found himself at a crossroads in 1992. Seven of the eight albums he’d produced for Ruthless Records between 1983 and 1991 had gone platinum, including his group N.W.A’s most recent opus, Efil4zaggin, which hit no. 1 on Billboard. But he wanted out, badly: His royalty payouts were too low, and he felt N.W.A founder Eazy-E and manager Jerry Heller were taking advantage of him. (Heller, who died in 2016, disputed these claims.) Desperately wanting to start a new label, he enlisted the help of Suge Knight, a former UNLV defensive end and the bodyguard of Dre’s confidant the D.O.C. Knight, who had famously hung rapper Vanilla Ice over a balcony to get him to sign over the rights to his hit song “Ice Ice Baby,” demanded Eazy-E release Dre, D.O.C., and several others from their Ruthless contracts. When he threatened to hurt Eazy’s mother and Heller if that didn’t happen, the diminutive rapper reluctantly signed the papers.

Dre was free of his contractual obligations, but legal problems still loomed. The most high profile of those was the civil suit brought by Dee Barnes, host of the Fox hip-hop show Pump It Up, who said that Dre brutally assaulted her in 1991 because of the way a segment on the show involving N.W.A and departed group member Ice Cube had been edited. After confronting her at an industry party, Dre “began slamming her head and the right side of her body repeatedly against a wall near the stairway,” kicked her in the ribs and stepped on her hands, and followed her into a bathroom to continue the assault after she tried to escape, Barnes said at the time. Dre, who pleaded no contest to misdemeanor battery charges stemming from the incident in August 1991, would eventually settle the suit out of court.

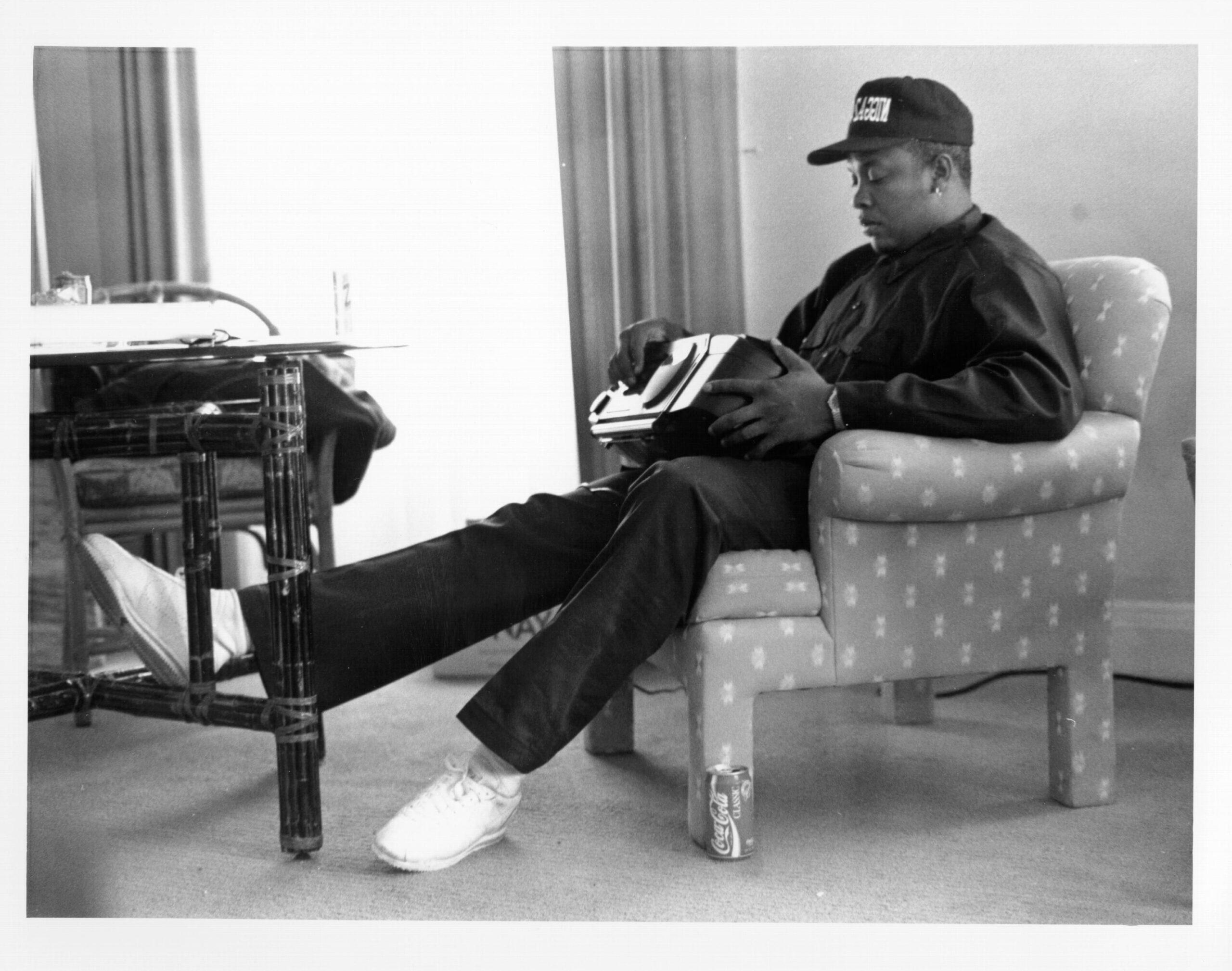

Against this backdrop, Knight, the D.O.C., record producer Dick Griffey, and a 27-year-old Dre founded Death Row Records with the help of seed money from Michael Harris, a businessman who was serving a sentence for drug charges and attempted murder. Soon, Dre and a horde of collaborators began working on what would become the label’s first release, which would double as Dre’s first solo album and a showcase for Death Row. The sessions for the project, which took place at the newly christened Death Row Studios in Hollywood and Dre’s Calabasas home, quickly became smoke-filled affairs—quite the change for someone who rapped four years earlier that he “don’t smoke weed or sess / ’Cause it’s known to give a brother brain damage.” Through that haze, a title emerged: The Chronic.

With the new studio, new freedom, and new botanical muse, Dre began crafting a sound that would redefine rap, both for his coast and the genre at large. It started with the spirit of George Clinton: “At the same time [Dre and I] were like, ‘We need to do some P-Funk–sounding shit,’” Dre’s Chronic cowriter, multi-instrumentalist Colin Wolfe, told Wax Poetics in 2014. “We wanted to make a real Parliament-Funkadelic album.” The influence is apparent on “Let Me Ride,” which samples “Swing Down, Sweet Chariot” on its hook, and especially on “The Roach,” a Mothership homage bordering on parody updated for 1992 Los Angeles. But Parliament had been sampled plenty of times before—the flower children in De La Soul scored their biggest hit with a flip of “(Not Just) Knee Deep” three years earlier, and Dre himself had mined George Clinton records for N.W.A’s albums.

What changed in The Chronic sessions was Dre’s approach. Hip-hop music at the time was largely beholden to production techniques created by its East Coast practitioners: jazzy samples from dusty records that sounded analog even as they were pumped through digital mixers. While Dre later said The Chronic was inspired in part by A Tribe Called Quest’s 1991 classic The Low End Theory, he would largely forgo direct sampling on his solo debut, instead asking musicians to replay melodies and bass lines. This came at a time when live instrumentation in hip-hop was seen as a gimmick at best and a faux pas at worst. But the undeniably thumping grooves gave the naysayers little ammo; “Nuthin but a ‘G’ Thang” doesn’t get its full-bodied sound by Dre simply running a Leon Hayward record through an S900.

Crucially, Dre added one signature element to many of the tracks: a high-pitched Moog synth line, à la the Ohio Players’ “Funky Worm.” Dre had previously attempted something similar on songs like N.W.A’s “Alwayz Into Somethin’,” and while Cold 187um—the producer from Ruthless Records group Above the Law—has repeatedly said he invented the sound, it took on addictive properties on The Chronic. Beats like the one on “Deeez Nuuuts” were meticulous blends of melody, bass, and pounding drums; they could blow out subwoofers while also worming themselves into a listener’s ears. Others sounded as suspenseful as any horror movie score, but the underlying groove drew the audience in. It’s not that the music on The Chronic was pop—it was undeniable.

The sound also had a name—G-funk—and suddenly, the man who desperately needed 1992 to break his way professionally had an aesthetic that would become the platonic ideal of West Coast rap for the rest of the decade.

“Everybody who walks has something he or she can do in the studio. Every person walking has some kind of talent that they can get on tape. I can take anybody who reads this magazine and make a hit record on him. You don’t have to rap. You can do anything. You can go into the studio and talk. I can take a fuckin’ three-year-old and make a hit record on him. God has blessed me with this gift.” —Dr. Dre, Rolling Stone, 1993

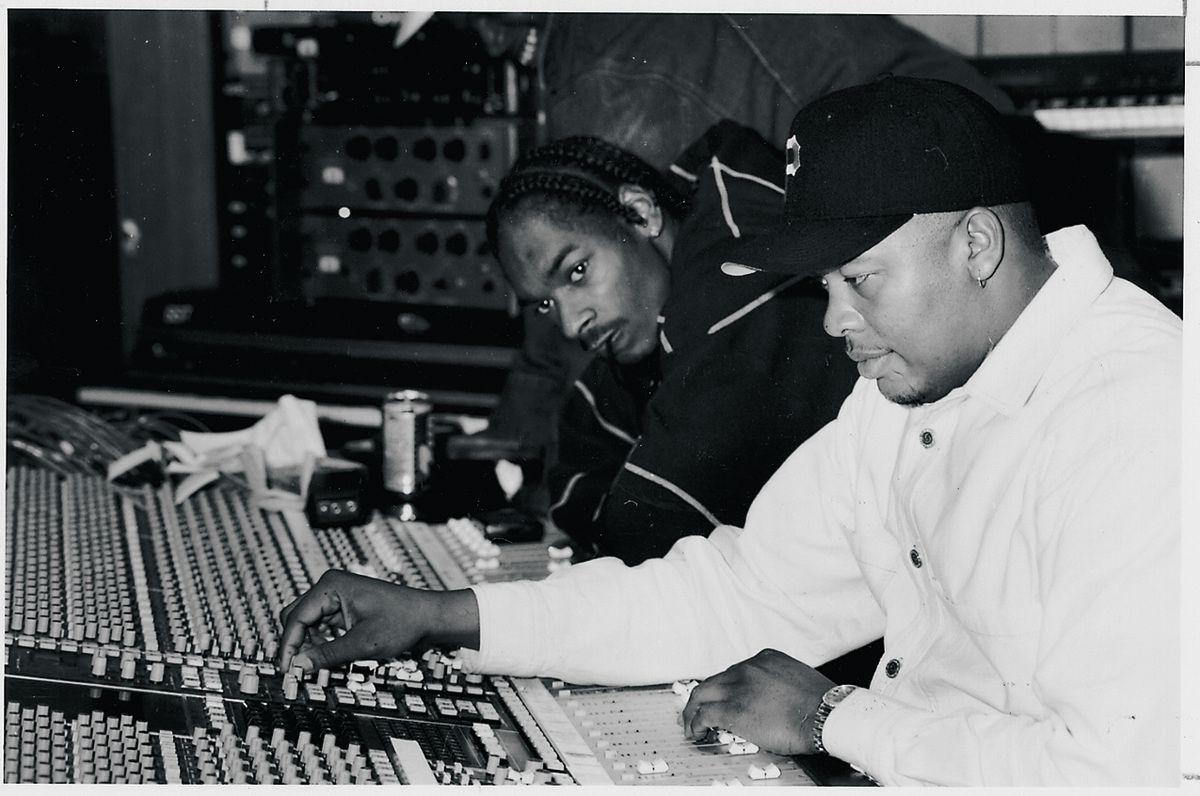

It’s easy to forget now after his nearly 30 smoke-filled years in the spotlight, but Snoop Dogg was an unknown quantity in 1992. Before then, the rapper born Calvin Broadus was part of a group named 213 with Dre’s stepbrother Warren G and street crooner Nate Dogg (who in 1994 would break out on their own with “Regulate”). Snoop had been reluctant to let Warren play Dre his rhymes until he thought they were good enough—this was, after all, the man behind N.W.A. “When he finally got a chance to hear me, I was ready,” Snoop said years later. Quickly, the producer invited the 20-year-old Long Beach MC to work with him. First, they recorded the title track for the 1992 Laurence Fishburne movie Deep Cover. By the time that became a minor hit, Snoop was firmly entrenched in the Death Row stable, riding shotgun in Dre’s 6-4.

There are a lot of voices on The Chronic that aren’t Dr. Dre’s—in fact, he has only one true solo song on the album (“A Nigga Witta Gun”) and there are several that he cedes entirely to his supporting cast. The other rappers all fill different roles: RBX sounds like a maniacal villain, future Dogg Pound member Daz comes off like the bridge between West Coast hip-hop’s past and then-present, Lady of Rage raps like the toughest of them all—with all the misogyny in her cohort’s lyrics, she’d have to. And at times, the repetitive nature of the content can be overbearing: The Chronic alternates between raucous partying and vague threats, while sometimes capturing both at once. But Snoop cut through all of the noise, his flow both ferocious and laid-back, his presence both menacing and inviting. One need not look any further than his star-making turn on “Nuthin but a ‘G’ Thang” to see why Suge and Dre saw him as someone they could build an empire around.

It’s likely the album flops, or at least fails to reach such lofty heights, without Snoop to ground it. Dre has always been better served as a director than a leading man, and while his rhymes aren’t quite as stilted as some contemporary reviews made them out to be, he’s missing a certain charisma. (“Let Me Ride,” one of the few songs on the album that Dre lyrically anchors, was The Chronic’s lowest-charting single.) It also didn’t help matters that he didn’t write many of his own lyrics—when he shouted-out D.O.C. by saying “no one could do it better” on “‘G’ Thang,” he was actually reciting lines his buddy penned for him.

The contrast between Dre and his deputy is clearest on “Lil’ Ghetto Boy,” a Donny Hathaway–sampling song that opens with clips from Birth of a Nation 4-29-92, a low-budget documentary that captured the Los Angeles Riots that occurred seven months before The Chronic’s release. As Dre clumsily recounts a fictional botched robbery, Snoop offers a plaintive meditation on the cyclical nature of violence and consequence, culminating in the lines: “And we expose ways for the youth to survive / Some think it’s wrong but we tend to think it’s right.” Amid all the garish violence, Snoop’s verses are the closest The Chronic has to a message.

But elsewhere, Snoop puts a smooth voice to some of the uglier moments on the record: the homophobic “Dre Day” disses aimed at Eazy-E, “Fuck Compton” rapper Tim Dog, and 2 Live Crew’s Uncle Luke, for some reason; the comically regressive posse cut “Bitches Ain’t Shit,” where Snoop debates killing his cheating girlfriend. The Chronic is sometimes cited as the first major album to make gangsta rap fun, and while it’s impossible not to get swept up in its more fantastic elements, it’d be tougher to swallow with Dre as its only leading voice, especially given his history with Barnes and other women who said that he assaulted them. And unlike our present day, when discussions over an artist’s actions play out in real time on social media, The Chronic was created in a world before mass internet access. If you weren’t reading Rolling Stone or paying attention to Kurt Loder’s MTV News updates, you likely didn’t know about Dre’s history of violence.

The controversy over the lyrical content, however, ultimately became a selling point. The early ’90s were something of a heyday for moral panics over rap music, a time when a soon-to-be president could score political points by repudiating Sister Souljah, when a metal band fronted by Ice-T was the most dangerous group in America, and when Rev. Calvin Butts steamrolled albums he deemed to be of questionable moral standing. C. DeLores Tucker, a former civil rights activist, took aim directly at the genre’s treatment of women: “I am here to put the nation on notice that violence perpetuated against women in the music industry in the form of gangsta rap and misogynist lyrics will not be tolerated any longer,” she said in 1993. “Principle must come before profit.”

What the likes of Tucker and Butts underestimated is that musicians in general, and rappers specifically, had long courted that type of attention. Dre specifically had seen the positive effect of controversies a few years earlier: N.W.A drew attention from the FBI and Secret Service with their single “Fuck tha Police,” which caused their sales to skyrocket. At a time when rap albums weren’t worth a damn without a parental advisory sticker, Dr. Dre had something that no parent wanted their kid to have—and that every kid wanted.

“It’s my business to know these things, and there’s no difference between the people that are going out and buying the Dre album and people that are buying Guns n’ Roses.” —Interscope promotions director Marc Benesch, Rolling Stone, 1993

Years before The Chronic was released, Public Enemy’s Chuck D dubbed rap music the “Black CNN”: It shed light on what was happening within the community, giving white America a glimpse of things it would otherwise miss. Conversely, Dr. Dre made a career out of turning that idea inside out. “You shouldn’t take it too seriously,” he told The New York Times in 1999. “It’s not like you’re going to go see a play or a movie or something and want to come out to be Rambo.’’ There’s a reason Dre opened his second solo album with the THX sound—it was all a summer blockbuster to him.

If nothing else, The Chronic sold that escapist fantasy to a group of people who had never experienced anything similar to the life it described. For suburban kids, the streets of Compton, California, felt like a different world—simultaneously a never-ending party and a place far more dangerous than where they called home. They wanted to be like Snoop. They wanted to wear a White Sox hat like Dre. They wanted in, without having to actually leave the comfort of their existing lives. The album debuted at no. 3 on the Billboard charts, was certified three times platinum, and has sold close to 6 million copies. At the time, it became the best-selling gangsta rap album ever, and record execs quickly realized they could make a killing by pushing more violent rap to this new audience. Just look at the Billboard charts: In the years before The Chronic, rap sales were dominated by gimmicky, pop-friendly MCs like Tone Loc, MC Hammer, Vanilla Ice, and Kris Kross. After Dre’s debut and Snoop’s 1993 debut, Doggystyle, changed things, more street-oriented artists like Tupac, the Notorious B.I.G., and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony became some of the most bankable stars in the business. Even Coolio, a former volunteer firefighter and LAX security officer, scored big by adopting some hardcore posturing on “Gangsta’s Paradise.” Gritty realism started to drive the rap market, even if it was all entertainment to Dre.

The album’s influence on mainstream rap began to sound a lot like the G-funk Dre brought to the masses. Soon, every rapper from Inglewood to Vallejo in search of a hit seemed to be combining trunk-rattling bass with high-pitch synths. None did it quite as well as the Doctor, though some came close—most notably Eazy-E, who expertly adopted the sound in his rebuttal to Dre. But Dre’s influence wouldn’t end there, even as he jumped ship to start his new label, Aftermath. In 1999, he’d unleash Eminem onto an unsuspecting listening public, offering a different kind of escapist fantasy for suburban kids. At the very end of the millennium, his 2001 would show just how cinematic an album could be. Four years after that, he helped build 50 Cent into a rap superhero with chiseled abs and an unforgettable origin story. These were popcorn movies committed to wax—big-budget productions that the public kept coming back to, even if they knew the plot lines weren’t entirely works of nonfiction.

With the myth of Dr. Dre largely debunked in 2020, the smoke around The Chronic has largely settled. He’s lived another full lifetime since he released his debut solo album. He’s also apologized publicly—though clumsily—for his violence against women. The label he built in the early ’90s crumbled, acquired by a toy manufacturer in a bankruptcy selloff and ultimately shuttered. Suge Knight is in prison for manslaughter; Dre made an ungodly amount of money off of headphones; Snoop Dogg is best friends with Martha Stewart. Essentially every bit of The Chronic’s facade has been shattered, and all we’re left with is the music. That’s the only thing that still feels transcendent: the bass as thick as ever, the drums just as hard as you remember them, and Snoop as casually great as you need him to be. There’s a reason Kanye West said that it’s the one album all hip-hop should be measured against. But while it’s a megalithic, canonical album that’s now in the Library of Congress archives, it remains a deeply personal listen.

In the past few years, if I’ve wanted to listen to the album, I’ve had to fish around for a pirated copy—which basically feels as dated as a Memorex tape at this point. But today, as the album hits all major streaming services, I look forward to legally firing up the album on my phone, even if the idea of The Chronic is no longer spellbinding. I’ll probably start at the intro and let it ride into “Dre Day”—I’ll let the bass go and feel some pangs of nostalgia, even though an iPhone smells nothing like a new cassette. But this time, I’ll also know what I’m getting myself into.