The Last Dance, ESPN’s 10-part documentary on the Chicago Bulls’ run to the 1997-98 NBA championship and the dissolution of one of the greatest sports dynasties ever, was supposed to premiere in June, just before the start of the 2020 NBA Finals. Then the entire world plunged into the depths of a pandemic, with the rampant spread of COVID-19 prompting global quarantines, casting significant doubt as to whether there ever will be a 2020 NBA Finals, and all but erasing the programming slates for sports networks (and, for that matter, sports websites) for the foreseeable future. To try to fill the gap—and after no small amount of public pleading from sports fans desperate for something new to watch—ESPN bumped the documentary’s air date up by nearly two months, slating the first installment for Sunday, April 19.

More than two decades removed from the final ride for Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Phil Jackson, Dennis Rodman, and Co., filmmaker Jason Hehir—who made the 30 for 30 on Michigan’s Fab Five in 2011, and Andre the Giant in 2018—combines archival footage from an NBA Entertainment film crew that followed the Bulls throughout the 1997-98 season with a ton of present-day interviews. The intended result: the most detailed look to date at not only what life was like at the end of the line for the most famous, celebrated, and historic team in American sports, but also at how all parties involved got there—how Michael Jordan got to be Michael Jordan, how the Bulls were built and became champions, how Jordan and the team turned into an international cultural phenomenon .... and, ultimately, how it all fell apart.

That’s a lot to get your arms around, even in 10 hour-long episodes. Here are some things we’re hoping to see under the microscope over the course of The Last Dance’s monthlong rollout.

The Aura and Spectacle of Prime Michael Jordan

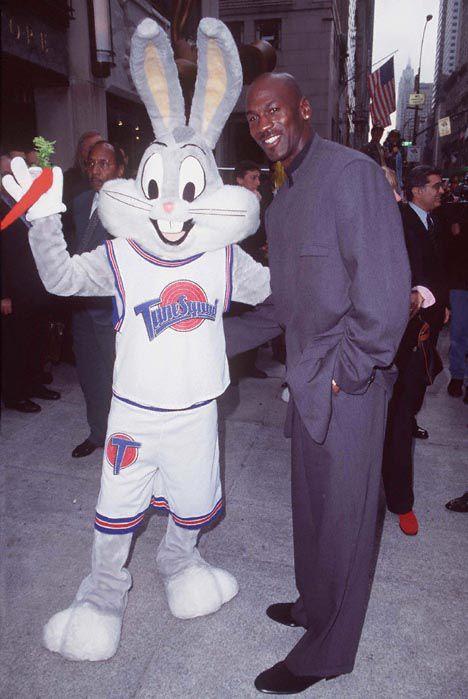

I had just turned 15 years old when the 1997-98 NBA season began, and it felt impossible to conceive of an athlete more famous, more iconic, and more omnipresent than Jordan. He’d come back from his interregnum in Birmingham and reclaimed his throne, winning the scoring title, regular-season MVP, Finals MVP, and the NBA championship in each of the previous two seasons. He was also less than a year removed from starring in Space Jam, which grossed more than $230 million worldwide thanks as much to the power of Jordan’s brand as to that of the Looney Tunes.

Jordan was on every magazine cover and every third commercial on television, or at least it felt that way. He was synonymous with sports, with winning, and with the cultural currency of coolness. As David Halberstam wrote in 1999’s Playing for Keeps, Jordan was “arguably the most famous American in the world, more famous in many distant parts of the globe than the president of the United States or any movie or rock star. American journalists and diplomats on assignment to the most rural parts of Asia and Africa were often stunned when they visited small villages to find young children wearing tattered replicas of Michael Jordan’s Bulls jersey.”

When the Bulls traveled to Paris in October 1997 for the McDonald’s Championship—a “growing the game” international tournament underwritten by one of Jordan’s most famous sponsors and spearheaded by NBA Commissioner David Stern—the Parisian newspaper France-Soir ran a full-page photo of Jordan on its front page under a headline that translated to, “The Idol of Young People Is in Paris.” The lede of that cover story: “Michael Jordan is in Paris. That’s better than the Pope. It’s God in person.” (The late-’90s French didn’t have the exclusive on theological Jordan comps; a decade earlier, they’d come from French Lick.)

Jordan sat down with Hehir for the documentary, granting the kind of access and interview that he’s rarely allowed in recent years. (The last time he participated in a big retrospective piece was with Wright Thompson for ESPN the Magazine in 2013.) One of the many things it’d be interesting to hear Jordan discuss, with the benefit of distance and perspective, is what it was like to be viewed that way—to be seen as “God in person,” to know that every eyeball is always on you in every room you ever walk into, to feel the weight of unparalleled fame on your shoulders with each step. He always made it look, publicly at least, like he wore it lightly, but could that possibly have been true? And, on a related note, how did the immensity of Jordan’s cult of personality impact everybody around him—his family, his friends, and his teammates?

Speaking of which ...

Jordan’s Famed Ruthlessness With Teammates

It’s been well-documented how brutal Jordan could be to his teammates; it was a through line of Sam Smith’s seminal 1991 book, The Jordan Rules. There are countless stories about how Jordan always viewed the rest of the Bulls as his “supporting cast” rather than his colleagues, about how he showed up and verbally berated them—“He has practically ruined Rodney McCray for us,” a team source told Sports Illustrated in 1993, by routinely getting in the reserve forward’s face during scrimmages and screaming at him, “You’re a loser! You’ve always been a loser!”—and about how his relentlessness sometimes spilled over into physicality. When a TV reporter asked Bulls center Luc Longley at the time for a one-word description of Jordan, he answered, “Predator.”

Jordan’s caustic nature stemmed from his unbridled competitive fire—not only how badly he wanted to win, but how unwilling he was to even countenance the concept of defeat. “It’s an addiction,” Jordan told Thompson in 2013. “You ask for this special power to achieve these heights, and now you got it and you want to give it back, but you can’t. If I could, then I could breathe.” Maybe his teammates could’ve breathed a little easier, too.

In Playing for Keeps, Halberstam writes that post-baseball Jordan was “a dramatically easier person to play with,” that the “almost gratuitous, punitive quality of his tongue had softened,” and that the man who entered the ’97-’98 season was more mature and better equipped for leading his lessers than previous models. In an as-told-to series that Jackson did with Rick Telander for ESPN the Magazine, though, the Zen Master recounts a story that still sounds fairly cutting: “The other day, I stopped the film after watching Luc Longley screw up again, and I just said, ‘Everybody makes mistakes. And I made one coming back here with this team this year.’ I meant it in sort of a lighthearted way. But then Michael says, ‘Me too.’ So it weighed pretty heavy on everyone.”

How did Jordan relate to teammates throughout what was, by all accounts, a grueling campaign due to the obscene pressure? Might the never-before-seen, behind-the-scenes footage lay out prime Jordan’s capacity for internecine viciousness in living color?

This question contains within it the broader matter of just how naked and unvarnished The Last Dance will be. According to Jim O’Donnell of the Daily Herald, “Jordan and [his] advisers [with Jump 23, which gets an ‘in association with’ credit on the documentary in ESPN’s press release] reportedly retain complete final editorial approval” of the project. We know Hehir’s got the footage; we know he’s got the interviews; we know he’s got the time to tell the story. It’ll be interesting to see how that story’s shaped, and in which (and whose) directions.

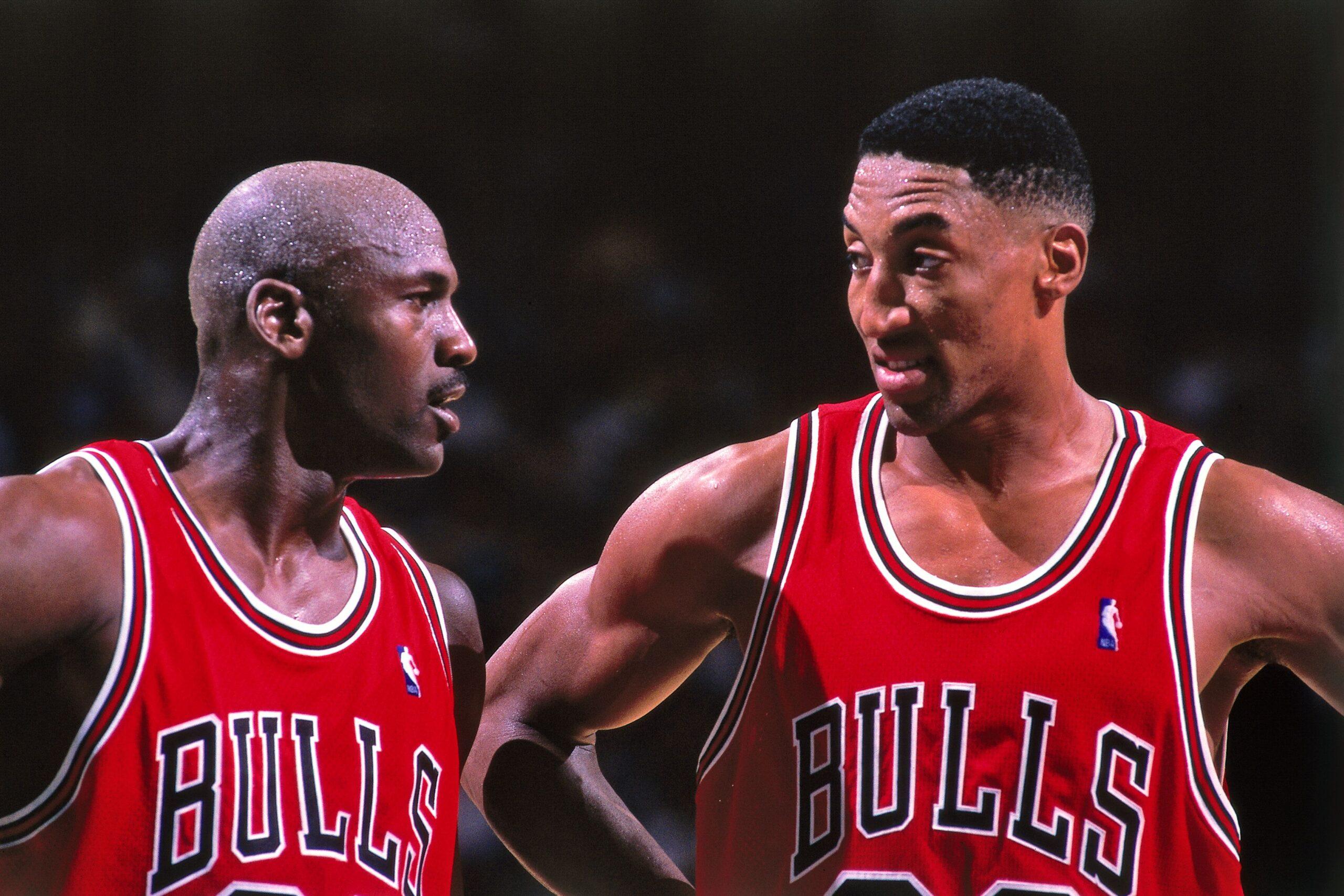

How Bad Things Got With Scottie Pippen

After missing just 19 games over the previous eight seasons, and developing into a perennial All-Star as Jordan’s second-in-command and later Chicago’s interim leader, Pippen missed the first 35 games of the 1997-98 season following left foot surgery. Without Pippen—the team’s primary ball handler, leading facilitator, secondary scorer, and best perimeter defender—the Bulls stumbled out of the starting block, struggling to score and get past younger, more energetic teams in his absence. (Well, relatively: After an 8-7 start, Chicago stood at 24-11, first in the East, by the time Pippen came back.)

Jordan reportedly seethed at Pippen for waiting until training camp to get that surgery—a choice born out of Pippen’s towering frustration with the Bulls and their medical staff—and at how it forced him to carry an even-greater-than-normal load early in the season. Jordan also reportedly didn’t appreciate that Pippen had left him with full responsibility for managing the mercurial Rodman, who didn’t sign his new contract with the team until just before the start of the season; Jordan Rules author and Bulls beat man Sam Smith insisted this contributed to the burnout that led Jordan to retire again after the season.

Pippen insisted in Basketball: A Love Story that “Michael never went after me,” but Jordan’s references to headaches and migraines tell a slightly different story. How did the dynamic between the two Hall of Famers play out in real time? What kind of look will The Last Dance give us at the relationship between Jordan and Pippen—one of the greatest one-two punches in league history, but also one of its most fraught?

For all his excellence, Pippen sometimes had a tendency to sulk; it made regrettable headlines when he sat out the final 1.8 seconds of Game 3 of the 1994 Eastern Conference semifinals after Jackson drew up the final play of the game for Toni Kukoc rather than him. He’d long been bitter about being underpaid for his contributions after agreeing to a long-term extension following Chicago’s first title, famously ranking 122nd on the league’s salary list in 1997-98 and as just the sixth-highest-paid player on his own team, making less than half of what Jackson made to coach. But he’d also been the topic of a ton of trade rumors over the years. Pippen for the draft rights to Grant Hill or Antonio McDyess. Pippen to Seattle for Shawn Kemp, Ricky Pierce, and a first-round draft pick. Pippen to Sacramento for Mitch Richmond and a first-rounder. Pippen to Miami for Glen Rice and a first. Pippen to the Lakers for Eddie Jones, though Bulls GM Jerry Krause was rumored to have asked for a young Kobe Bryant, too. (This reportedly made Jordan laugh.)

Pippen had grown increasingly frustrated with Krause dangling him, calling Chicago’s GM a “compulsive liar,” and saying on multiple occasions that he wanted the Bulls to just trade him and be done with it. Nothing ever happened, though—just a streak of unrealized rumors that continued ahead of the ’97 draft, when Krause reportedly looked to move Pippen to Boston for high lottery picks (that evidently might have been used to draft Tracy McGrady) and cap space, and during the season, when Pippen again asked to be dealt only to stay put. So Pippen spent the season hurt, emotionally and physically, as he and everyone else waited for what seemed like the inevitable. After the season, and the subsequent 1998 lockout, Pippen left the Bulls for the Rockets in a sign-and-trade; he finally got his payday, but he had to leave Chicago to get it.

How much did all that drama contribute to the heavy atmosphere surrounding the team? And two decades later, how do Pippen and the other principals involved view the shake he got in Chicago—the rare case of a top-50 all-time player who was still overshadowed for literally the entirety of his career? (I love the way J.A. Adande put it in 2010: “Put it this way: Kobe Bryant has come a lot closer to replicating Jordan than anyone has come to duplicating Pippen.”)

Toni Kukoc’s Polarizing Role

Krause loved Kukoc, a star for his domestic club in the EuroLeague and for the Yugoslavian national team, and used the second pick in the second round of the 1990 draft to snap up his rights. (For a good look at Kukoc’s generation of Yugoslavian stars, including Drazen Petrovic and Vlade Divac, I’d highly recommend the 30 for 30 documentary Once Brothers.) The scout-turned-GM invested years, and a rich contract, in convincing Kukoc—at that point regarded by many as the best player in Europe—to make the trip across the Atlantic.

That rubbed several Bulls the wrong way—especially Pippen, whose contract Krause reportedly balked at extending to ensure Chicago had the money to bring Kukoc over, and who teamed with Jordan to give Kukoc an awfully rude welcome when their paths finally crossed at the 1992 Olympics. In Dream Team, Jack McCallum’s fantastic book on the 1992 U.S. Olympic squad, former NBA public relations chief Brian McIntyre says, “I distinctly remember Scottie talking about it, and I can still hear him saying, ‘I don’t want Kukoc taking my money. That’s my money.’”

That treatment continued once Kukoc finally joined the Bulls. “I know it is always hard for the stars on a team to accept someone new, but I didn’t expect him to make it that bad,” Kukoc said in 1995. “I never had a problem with him; it was always something he felt.” (Perhaps Pippen wondered whether Krause’s affinity for Kukoc, who’d played a similar point forward role overseas, might have played a part in all those trade talks.)

But despite the rough road he encountered upon his introduction to Chicago, and the challenges he faced in adjusting to the physicality and defensive responsibilities of the NBA, Kukoc found his way, becoming a valuable sixth man. With Pippen injured to start the season, that value only grew, as he slid into the starting lineup and averaged about 14 points, four rebounds, and five assists per game, teaming with Ron Harper to fill the playmaking gap on the wing until Pippen could get back.

Kukoc never ascended to the sort of stardom in the NBA he’d enjoyed in Europe, but he earned respect, winning Sixth Man of the Year honors in ’95-96; he even eventually appeared to win over Pippen, whom Jackson described as “cheer[ing] wildly” for Kukoc from the bench. (Pippen even argued last year that Kukoc should be in the Hall of Fame, despite coming over “as one of the enemies.”) That doesn’t mean everything behind the scenes was smooth, though.

In the as-told-to diaries for ESPN the Magazine, Jackson wrote of Kukoc, “Toni has started 13 or 14 games, but he’s not happy either. He’s been bitchy and whiny. The guys tell me he hasn’t been in a good mood. I just keep asking him to get his mind where ours is. He wants to start, so I can’t figure out why he’s unhappy. Harper diminishes his game for the good of the group, but Toni is sort of a maverick.” (Which maybe helps explain why they tangled; it takes one to know one, after all.) It’d be cool to get a clearer view of how a talented, curious, and often overlooked player fit into the larger Bulls puzzle.

Did the Bulls Ever Really Sweat?

In Jordan’s first two full seasons after baseball, the Bulls went 22-3 in the Eastern Conference playoffs, dropping only a single game each to the Knicks, Hawks, and Heat. The stiffest in-conference test of the second three-peat, by far, came in the 1998 East finals. In Larry Bird’s first season as a head coach, Indiana won 58 games, ranking sixth in the league in offensive efficiency behind the sharpshooting of Reggie Miller and Chris Mullin, and the steady playmaking of Mark Jackson. They also finished fifth on the other end, thanks to the bruising work of Dale Davis and Antonio Davis, and the hulking frame of 7-foot-4 Rik Smits in the middle.

That Pacers team was damn good—Jackson called winning Game 1 against them “escaping”—and came back from deficits twice in the series. Indy pushed the Bulls to the limit, forcing Jordan to a Game 7 for the first time since 1992; the Pacers raced out to a 20-7 lead in Chicago in Game 7, and led with just under six minutes to go. So: How tight did things get? Did anyone’s palms get sweaty in those final six minutes?

What about against Utah in the Finals, when virtually the entire non-Jordan portion of the team was hobbled or dragging? That Jazz team was awesome, owners of the no. 1 offense in the league behind the vaunted Stockton-to-Malone pick-and-roll. Utah had won more than 60 games in back-to-back seasons, and went a torrid 31-5 after the All-Star break to take the no. 1 seed in a conference that featured three 60-win teams.

The Jazz came back from down 2-1 to the Olajuwon-Barkley-Drexler Rockets to win in Round 1, then smoked the Duncan-Robinson Spurs in five, and swept Shaq’s Lakers to set up a championship rematch with the Bulls. Three of the four games Utah lost in the Finals were by two or fewer possessions. (The other one was an all-time 42-point ass-kicking, though, which might have assuaged any concerns.)

We’ve heard so much about the heart of a champion, the focus, the determination, and so on. But that can’t have just been a static constant, right? Did the greatest NBA dynasty of our lifetimes ever wobble as it approached the finish line? Maybe not—Jackson wrote after the Finals that Jordan “was calm during this Jazz series, and really enjoyed it.” Will the reality match the myths?

As “the Worm” Turns

Let’s not forget: Dennis Rodman was on this team.

Rodman needed some time to get revved up after signing his contract just a week before the season. Even at age 36, though, he was still a do-it-all-but-score monster, leading the league in rebounding for the seventh straight season and playing more minutes than anyone on the team save Jordan. Getting him focused, though, evidently remained something of a lift: At the time, according to Smith, Jordan said that “when he had to talk to Rodman he’d grab him by the temples, plead for Rodman to look him in the eye, and then tell Rodman what to do. Jordan said it was how he talked to his 8-year-old.”

In fairness, Rodman did have some other stuff going on. For one thing:

After Game 3 of the Finals, Rodman flew the next day to Auburn Hills to be on WCW Monday Nitro, rejoining Hulk Hogan and the New World Order (with whom he’d wrestled the previous year) in an effort to start a feud with Diamond Dallas Page and Karl Malone (who he was actually playing against in the Finals!) that would culminate at a pay-per-view event in July. Rodman reportedly got permission from Krause and Co. to leave, but it’d be interesting to hear about how Rodman’s departure went over while everyone else was focused on finishing off a three-peat. I eagerly await Bill Wennington’s comments on how the nWo turned into wrestlecrap.

The wrestling angle might not be the half of it, though. From Jackson’s as-told-to with Telander: “The point is Dennis has to get his motor going himself. What is helping now is this relationship he’s started with Carmen Electra, whoever she is. Is she on TV? [Editor’s note: Yep! On Baywatch. She also worked in print, so to speak, making several appearances in Playboy.] And she is his inspiration. He goes out and plays for her. But God forbid he has a bad game, because then it’s impotence time.”

Electra was on the list of interviewees for the doc. I’m guessing we’re going to hear more about, um, all of that.

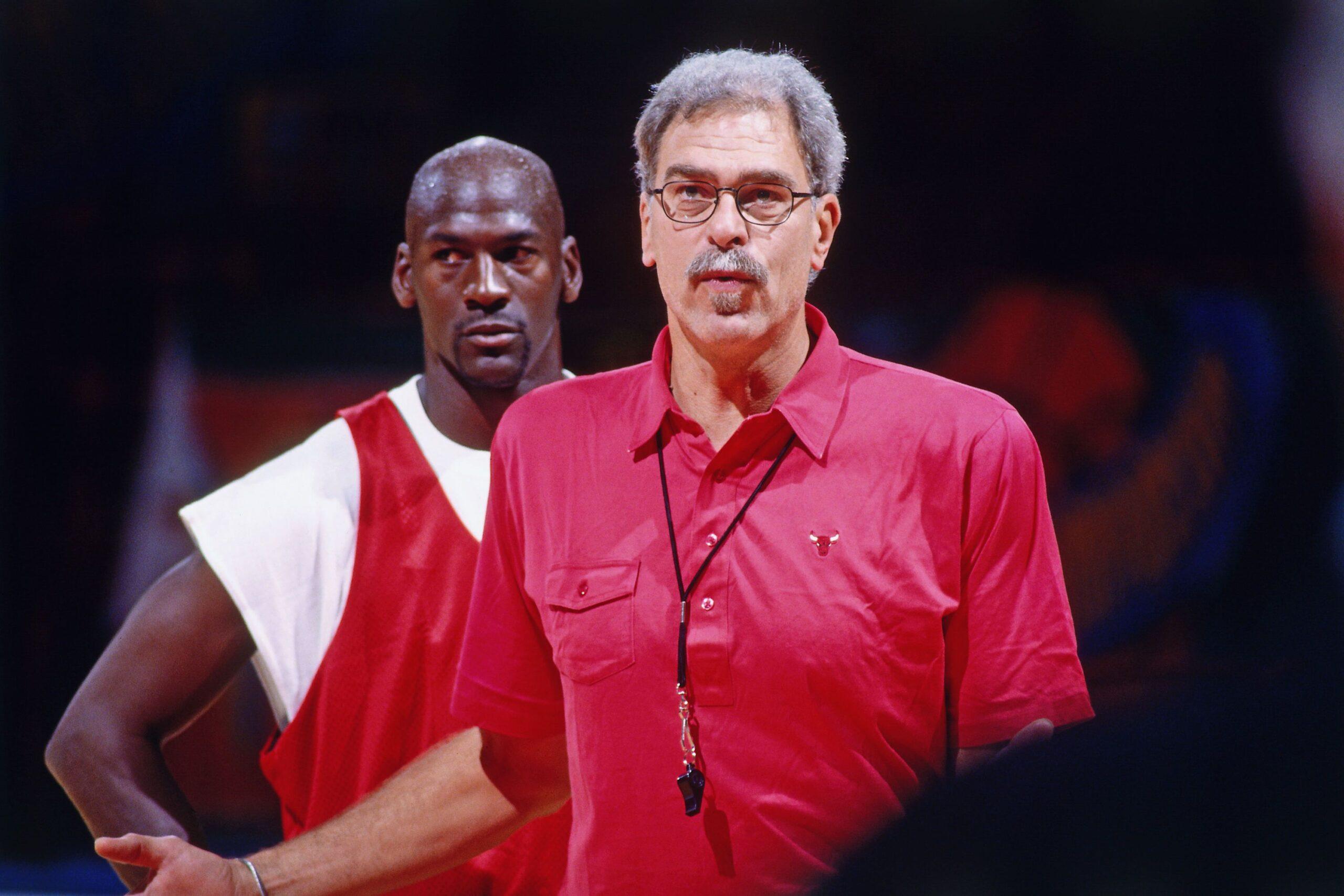

How Did an Out-the-Door Phil Jackson Impact Everyone Else?

After a contentious negotiation, Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf and Jackson’s agent agreed to terms on a one-year deal that would pay Jackson $6 million to coach the 1997-98 Bulls. And only the 1997-98 Bulls. “Phil only wanted to coach one more year, and we only wanted Phil to coach one more year,” Krause said, according to Selena Roberts of The New York Times.

That was the way it came out in The Gray Lady, anyway. Jackson said before the start of the season that it would be his last, and that “wild horses couldn’t drag [him] back” to Chicago to work for Krause, who seemed to resent how much credit Phil got for Chicago’s run of glory (and, by contrast, how little he received himself). And in Playing for Keeps, Halberstam quotes Krause as exploding at Jackson, “I don’t care if it’s eighty-two-and-oh this year, you’re fucking gone.” The vibes, it seems, were not great.

That wasn’t solely due to the toxic nature of the Krause-Jackson relationship. Jackson had in the past spoken about coaches having a shelf life: “We felt seven years of intensity of coaching an NBA club is really up to a limit. Then you’ve got to stop and evaluate where you are as a coach and where you are in your personal life.” Past that, he felt, the players stopped listening to you anyway. Jackson had been the boss in Chicago for nine years at that point, past his expected expiration date, though the turnover in the team brought about by Jordan’s sabbatical had helped keep things fresh. And besides: Jordan had made it clear that he’d only play for Jackson. So, for the time being, Phil stuck around.

Even so: Everybody knew that Jackson was gone come season’s end, and with him went Jordan, and probably Pippen, and probably Rodman. The entire project was finite, and it seemed like everyone blamed someone else for it; even during the Eastern Conference finals, Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf put all of the “last dance” talk and turmoil squarely on Phil, and said management/ownership had made no statements or indications that they wouldn’t bring everybody back if they wanted to be there. Whether or not that was true, and while Jackson insisted he wasn’t looking to go anywhere and coach right away, he did cop to a wandering eye: In his series with Telander, Jackson wrote about starting to watch the Lakers late in the season, and fantasizing about the challenge of getting Shaquille O’Neal—the kind of monster low-post threat he’d never had in Chicago—to submit to the precepts of his preferred triangle offense.

When every player in the locker room knows the team’s getting blown up at the end of the season, how much does that influence the way everyone feels, behaves, and plays in the meantime? How did Jackson manage to keep it all together all the way through the Finals? Does he have second thoughts about the way things shook out? We know Phil’s not shy about sharing his opinions; here’s hoping he gets plenty of room to do so.

What Do We Make of Jerry Krause?

There’s no way to tell the story of the Bulls without Krause, who ran basketball operations for the franchise from 1985 through 2002, who plucked Jackson out of the Continental Basketball Association in 1987, and who acquired every player on the rosters of the Bulls’ six championship teams ... except for Jordan, who was drafted in 1984.

That is, of course, a fairly gigantic exception. It sat at the heart of a yearslong battle for control, credit, and commemoration behind the scenes in Chicago—one that Jordan laid bare in his infamous Hall of Fame induction speech in 2009.

“I don’t know who invited him—I didn’t,” Jordan said. “He was a very competitive person, I was a very competitive person. He said, ‘Organizations win championships.’ I said, ‘I didn’t see organizations playing with the flu in Utah. I didn’t see organizations playing with a bad ankle.’”

Krause insisted the quote Jordan seized on wasn’t quite right; in his telling, it was “players and coaches alone don’t win championships, organizations win championships.” But the point stood, and it incensed Jordan, who’d butted heads with Krause for years, ever since the executive kept Jordan from returning to the court after breaking his foot in 1986, in part to protect against reinjury, and in part to improve Chicago’s draft position.

“He said, ‘You’re Bulls property now, and we tell you what to do,’” Jordan told Sports Illustrated in 1993. “I was a young, enthusiastic kid, and that just made me realize this was a business, not a game. We never hit it off after that.”

Jordan raged against Krause’s personnel decisions—drafting Brad Sellers over Johnny Dawkins, trading Charles Oakley for Bill Cartwright—and took to insulting Krause about his weight. He mooed when the exec got on the team bus. He called Krause “Crumbs,” a dig at his love of donuts.

Jordan wasn’t alone in his feelings toward Krause; the GM’s protracted conflict with Pippen was the stuff of legend. He clashed often with Jackson, who suspected (correctly) that Krause planned to replace him at the earliest opportunity with Iowa State head coach Tim Floyd (woof), and who once omitted Krause from his famed practice of giving everyone a book to read because “I couldn’t find it in myself to give him something of value.”

Many of those relationship breakdowns reportedly stemmed from Krause’s lack of interpersonal skill; it’s not for nothing that the Chicago Reader’s 1990 cover story on Krause ran under the headline, “Nobody Cheers for Jerry Krause.” As Halberstam wrote in Playing for Keeps, he was “exceptionally maladroit in almost all dealings with all kinds of people, his own emotional vulnerability so manifest that he had trouble handling a position of power with anything near the requisite grace needed in so charged an atmosphere.” That contrasted mightily with the likes of Jordan, Jackson, and Pippen, who tended to exude grace on and off the court.

And yet: Krause was an excellent lifelong scout (in one telling, he “discovered” Earl Monroe) who spotted and drafted Oakley, and Pippen (when, it should be noted, Jordan wanted Joe Wolf or Kenny Smith), and Horace Grant, and Kukoc. He was the exec who snagged rotation pieces like John Paxson, Steve Kerr, and Bill Wennington on bargain deals, and who pounced on opportunities to import a distressed asset like Rodman. There would’ve been no dynasty without Jordan, obviously, and as much as Krause yearned for the chance to build one without Michael, his “Baby Bulls” never came close to restoring the franchise to prominence. But would another exec—one who focused more on keeping crumbs off his shirt than on looking anywhere and everywhere for the right talent—have found the pieces to round out the championship puzzle as well as Krause did?

The truth about how much credit Krause—who died in March 2017, only posthumously receiving enshrinement in the Hall of Fame—deserves for the Bulls’ run, and how much blame he deserves for its demise, probably lies somewhere in the middle. (In a statement after Krause’s death, Jordan called him “a key figure in the Chicago Bulls’ dynasty of the 1990s [who] meant so much to the Bulls, the White Sox, and the entire city of Chicago”—the kind of roses it would’ve seemed unthinkable he’d throw two decades earlier.) How much got caught on camera, and how carefully it’s presented, could go a long way toward clarifying matters.

Will The Last Dance Change the Way We See Jordan?

The last time Jordan sat down for something substantial, he didn’t come off as particularly remorseful or reflective; Thompson’s 2013 feature told the story of a man struggling to come to grips with what once was, but is no longer, and never will be again. Learning to live with that reality, he said, “is a process.” Has he moved along over the years? Will revisiting those glory days in such great detail help, or hurt? Have the hard edges that became infamous back then—the barbs for teammates, the vicious competitive streak—finally begun to round off? Does the greatest of all time have any regrets? If he does, would he dare share them—and if he does, how might it alter the way we’ve come to view the most uncompromising and singular force in basketball history?

The more I think about those questions, though, the more I think about all the people who weren’t 15 or older when the Bulls set out for ring no. 6. Millions of young basketball fans—the ones who call LeBron or Steph or someone else the GOAT, and will brook no argument from us graybeards—have no real frame of reference for what an absolute five-tool killer Michael Jordan was on the court. YouTube highlights can detail only so much. You have to pull back to see it all—the precision of the footwork, the depth of the bag, the unbelievable athleticism, the preternatural instincts, the unbridled intensity.

A whole lot of people are about to be introduced to the facts of the case. It’s enough to make you wonder whether, by the closing credits of The Last Dance, the biggest takeaway we have isn’t how close LeBron and Co. are to catching the ghost, but how far away they really are.

Why It All Ended

The answer, I’m guessing, will amount to something like “all of the above,” with a side order of “five of the top seven players on the team were between 32 and 37, and completely out of gas or near it.” But how we get there—how the footage and interviews tell the tale—matters, as does the prospect that Hehir can unearth new things to say about one of the most covered and discussed players and teams in modern sports history. That’s an awfully tall task. But it’s not like we’ve got anything else to watch.