On March 28, President Donald Trump conducted a conference call with commissioners and executives from 13 North American sports leagues, ranging from century-old institutions like the NFL, MLB, and NHL to 1990s creations like MLS, UFC, and the WNBA. Trump reportedly told the league representatives that he hopes fans can return to live sporting events by August or September. At a White House briefing later that day, Trump proclaimed, “I want fans back in the arenas,” adding, “They want to see basketball and baseball and football and hockey. They want to see their sports.”

Although the president extended invitations to organizations that rely on figurative horsepower (NASCAR and IndyCar), literal horsepower (the Breeders’ Cup), and even prewritten scripts (the WWE), Pete Vlastelica was not invited to join the call. Vlastelica is the commissioner of the Overwatch League and the president and CEO of Activision Blizzard Esports, which operates both the OWL and the Call of Duty League (CDL). Perhaps he didn’t get a dial-in number because the president is as much a stranger to esports as he is to email. In a sense, though, the OWL head honcho didn’t have to participate, because Vlastelica’s league had already resumed operations. On the day of the conference call, the OWL returned from a two-week coronavirus-caused break to deliver a standard slate of five matches between teams based in China, South Korea, Canada, and the U.S. (The CDL will follow suit this Friday.) The difference between the OWL and the leagues represented on the conference call is that the OWL’s action can take place entirely online.

Sources familiar with the conference call told ESPN that NBA commissioner Adam Silver said American sports leagues were leaders in suspending operations as the health crisis worsened nationally and that they “would love to lead the way in restarting the economy once there is an ‘all clear’ from public health officials.” The problem with the leagues leading any post-pandemic economic awakening is that for safety’s sake, well-attended sporting events should probably be among the last cultural touchstones to return. Although the president has been prone to false optimism and misleading statements about how quickly the country can overcome COVID-19, the leagues are well aware of the obstacles to getting back to business as usual, which is why many of them have discussed sequestering players and playing in empty arenas to avoid canceling their seasons.

The OWL, which debuted in 2018, staged most matches throughout its first two seasons at the Blizzard Arena in Burbank, California, which has a capacity crowd of 450 fans. Season 3 marked the league’s transition to a traditional-sports structure in which each of the league’s 20 teams—which are located across Asia, North America, and Europe—would host home stands in its local market. Only a handful of those live events took place as planned. The spread of the coronavirus forced the league to call off events region by region—in China in late January, in South Korea in late February, and everywhere else on March 11. Yet the OWL never seriously discussed scrapping its season, which started on February 8 and was originally scheduled to end in early August. (The revised season length and end date have yet to be finalized.) “We always knew that we had this option to move online,” Vlastelica says, adding, “We all felt that so long as we could get that working quickly, which we did after just a two-week hiatus, there would be no need to cancel the season.”

The esports world hasn’t weathered the pandemic without disruptions of its own. Many events have been canceled or postponed. Some proceeded sans live audiences. And others, like the LCS and LEC League of Legends leagues, the ESL’s Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Dota 2 pro circuits, and the OWL and CDL—a 12-team league that launched this year and has 10 owners in common with the OWL—have pivoted to an online-only model (although some have persisted in producing streams in studio). The OWL became the first geolocated league of any kind (electronic or traditional) to resume play, albeit without the planned in-person component.

“This is the first time in the history of the Overwatch League that we’ve played official league matches online,” says Overwatch Esports VP Jon Spector. “But if you go and you look at the broader history for Blizzard Entertainment and the esports industry more broadly, even with the rest of our Overwatch Esports programs, we’ve played matches online and run events purely online many, many, many times.”

Traditional sports leagues have little choice but to contemplate problematic and potentially implausible plans as they wait for the crisis to subside. In esports, though, the games can go on by going online. That’s good news for existing fans of competitive gaming, but it may also represent an opportunity for esports to break through to a sports-starved audience that wouldn’t typically pay attention to online games.

“If we can play a role in bringing people into esports for the first time because they just miss competition at the highest level and we’re bringing this … competitive entertainment product to people who otherwise don’t have live options, then that’s great,” Vlastelica says. But it may take more than a temporary pause in traditional sports to make converts of consumers who’ve heretofore stuck to ball, bat, and stick sports.

For many Americans, coronavirus-related isolation has meant more screen time. Although streaming TV networks have seen their audiences swell, much of that time spent staring at flickering light is devoted to video games, both by regular gamers who’ve increased their activity and by lapsed gamers who’ve returned to the fold.

A mid-March report by investment bank Cowen Inc. provided a positive outlook for gaming relative to other industries. “In the near-term at least, we would expect containment measures to be (if anything) a positive for engagement across the industry,” the report said. Citing gaming’s “very high value-to-price proposition” and strong performance in prior recessions, Cowen concluded, “we believe that demand is likely to remain quite robust.” Peter Vahle, a forecasting analyst for market research company eMarketer, says that “In-home entertainment, such as streaming services and gaming consoles, is one of the few categories people are willing to spend more money on during the pandemic, alongside essential products like food and household goods.” Humans don’t want to be hungry, and they also don’t want to be bored.

The day after Cowen’s report was published, Verizon disclosed that gaming traffic during peak hours was up 75 percent since widespread self-isolation went into effect (compared to a 20 percent uptick in overall web traffic), even amid more frequent network outages. Both Steam and Twitch have recently set records for concurrent users; Twitch and its livestreaming competitors have experienced upticks in hours watched from February to March, and this week, Riot Games’ new shooter Valorant nearly wrested the Twitch viewership record away from Fortnite. Esports audiences are notoriously tricky to measure, but it’s not surprising that gaming and streaming would skyrocket as people spend more of the day indoors.

None of those numbers necessarily suggests that esports leagues are attracting fresh fans as opposed to tightening their hold on existing spectators. In 2015, the webcomic Loading Artist published a strip that highlighted the common ground between fans of esports and fans of traditional sports. Both enjoy watching high-level professional performers compete in activities that they’ve likely pursued themselves on a more casual level. They just don’t often find the same activities entertaining. As the strip points out, they may even dismiss each other’s pastimes as unworthy of attention, in spite of the similarities between them.

The absence of traditional sports sets up the possibility of a different final panel. Without the option to tune into soccer, would the black-and-white blob in the red shirt give the game the black-and-white blob in the green shirt is watching a chance? Or would the traditional-sports fan still scoff at the video-game viewer and start streaming Tiger King instead? And if they did attempt a cultural exchange, would they gain a greater appreciation for their respective sports of choice, as Penny Arcade once envisioned?

Or would sitting side by side only make them double down on their differences, à la PvP?

“It’s really hard to say whether or not traditional sports fans are going to move over to watching esports because of this specifically,” Vahle says. What we can say is that for many fans of older-school sports, switching to esports would require overcoming a deeply ingrained indifference, if not aversion or outright enmity.

From March 20 to 22, Morning Consult polled 2,200 American adults on what they wanted to watch as alternatives to long-established live sports. Only 25 percent of self-identified fans of traditional sports described themselves as avid or casual esports fans. (Men, millennials, and members of Gen Z were more likely than women or older respondents to include themselves in one of those categories, and avid fans of traditional sports were more likely to be avid or casual esports fans than casual sports fans or non-sports fans were.) Only 19.6 percent of self-identified sports fans indicated that they were somewhat or very interested in watching an esports competition as an alternative to live sports—a figure almost identical to the 19.1 percent of all adults who described themselves as esports fans. In other words, existing esports fans want to watch esports, but very few others can see themselves starting now. (Admittedly, an additional 16.9 percent of sports fans reported being “not very interested” in watching esports—so they’re saying there’s a chance.)

According to the poll results, sports fans are less likely to turn to esports in the absence of traditional sports than they are to watch sports documentaries, classic games, sports talk shows, or what Morning Consult called “obscure sports.” Essentially, traditional sports fans would rather watch reruns, people talking about postponed sports, or whatever’s on ESPN8: The Ocho (marble runs, cherry pit spitting, sign spinning, cup stacking, etc.) than give esports an audition. On the subject of esports, most traditional-sports fans sound like Vanessa Kensington rejecting Austin Powers: They wouldn’t watch esports even if it were the last sport on earth—which, for now, it almost is.

Vanessa and Austin eventually got together (although the honeymoon didn’t last long). Maybe mainstream sports fans just think they wouldn’t like esports because they haven’t tried it. It’s true, though, that depending on the league, the transition from traditional sports to esports may not be an easy one. Many esports are as dramatically different from each other as MLB and the Breeders’ Cup, and a 2017 study found that 70 percent of esports spectators watch only one game. According to Vlastelica, even Overwatch and Call of Duty have a “single-digit-percentage overlap between the two competitive scenes,” with the more realistic-looking Call of Duty hewing closer to typical traditional-sports demographics and the more fantasy-oriented Overwatch skewing slightly younger and more female. As Penny Arcade once observed (using another online Blizzard title as an example), competitive gaming can be complicated even for experienced gamers. (Then again, football can be complicated even for football fans.)

When I asked members of the Facebook group for my FanGraphs baseball podcast, Effectively Wild, whether any of them had explored esports as a traditional-sports substitute, most said no, even though the demographics of the group are similar to those of the esports audience. Many cited an intimidating learning curve as a dissuading factor. Group member Cody Brock says he started streaming PUBG for the first time because baseball wasn’t on and he “ran out of Netflix,” but Brock was already a PUBG player, which made streaming more enjoyable. “You don’t need to be an athlete of any kind to see [LeBron James] jump and just know that it’s absurd,” he says. “When you’re watching a game like [PUBG], everybody runs the same speed, jumps the same height. So it requires a bit more involvement from the viewer to understand what’s making the difference.”

If unfamiliar content is the biggest barrier to entry, digital versions of traditional sports could become a gateway to esports for fans who are seeking out simulacra of the sports they know and love. Many old-school sport franchises have invested in esports, and many non-esports athletes (who fall squarely into the esports age group sweet spot) stream semiseriously. Minnesota Twins pitcher Trevor May, who streams for Luminosity Gaming and cofounded an Overwatch stat platform, is one of the most active non-esport athletes in the esports world. May has more than 160,000 followers on Twitch, where he’s spent much of his unscheduled break from baseball streaming a variety of titles. As someone who spans both sports worlds, May can testify to the disconnect between the two camps.

“I do think there is some crossover, a lot more so for NBA/NFL fans, but not quite as much as you’d think yet,” May says. “The macho elements of sport I think overpower it a bit, especially in sports fans older than 30 that didn’t have a ton of video game options growing up. I do think esports could satisfy that need a bit, though, especially when there’s an underdog or titan-falling-type story in play. It’s all about the stories that are being told.”

Last month, May participated in a players tournament in MLB: The Show, and some MLB broadcasters have practiced for the postponed season by calling simulated contests in The Show. NBA and Premier League teams have presented simulated, video game versions of canceled contests, and players from the NBA and La Liga have held tournaments in NBA 2K and FIFA, respectively. On Sunday, ESPN2 aired Madden, F1 Esports Virtual Grand Prix, and NBA 2K events as part of a 12-hour “Esports Day” programming package that also featured footage from Rocket League and Apex Legends. In the short term, traditional-sports fans may have a harder time avoiding esports even if they try: On Wednesday, ESPN announced a partnership with Riot to broadcast the League of Legends LCS spring playoffs, and the Overwatch League, which streams on YouTube Gaming, is also reportedly in talks to return to linear TV.

Another member of the Effectively Wild Facebook group, Jacob McArthur Mooney, says he’s “never really been a video game guy,” but since his preferred sports disappeared, he’s been following simulated Madden and MLB: The Show franchises and rooting as he would for his real-life teams. “I really like it,” Mooney says. “I would suggest maybe it’s filling two holes I’ve lost in The Current Circumstances, one being chatting with friends in a casual way around a piece of work and the other being watching the physical experience of athletes being athletes. Also, I think the simulated outdoors might help.” Mooney stresses that the connection to sports he’s followed for years is still the hook for him. “I don’t think I’d watch someone play Fortnite,” he says, but “one can never be certain how desperate one will get.”

For non-esports fans looking to make the online leap, digital motorsports offers the easiest sell. NASCAR’s iRacing series, which pits real racers against each other on realistic-looking courses via sophisticated simulation rigs, dates back more than a decade, but its appearances on Fox Sports 1 and NBC Sports since the suspension of physical races have catapulted it to greater prominence (and, in contrast to the 2K tournament, esports-record ratings). On a Monday conference call with media members, NBC Sports executive producer Sam Flood touted iRacing’s singular appeal among physical sports’ online analogues. “The drivers are actually manipulating the machines in iRacing, and someone manipulating a player on a court is very different, and a different skill set, than driving the car,” Flood said. “So I think it’s tougher with other sports.”

On the same call, pro racers including Dale Earnhardt Jr. and Parker Kligerman praised iRacing’s veracity, with Earnhardt sounding almost ready to take his hands off the real wheel for good. “I’ve been a sim racer for two decades and love it,” Earnhardt said. “I can’t get enough. I just needed an excuse to do it more, so this has been fitting right into my plans of being at home and racing on a simulator.” Earnhardt eventually admitted that because iRacing lacks the at-track engagement of an in-person race, it’s “not as good as the real thing,” but he concluded, “It’s really the only thing we’ve got going.” Small wonder, then, that on Sunday, pro racer Bubba Wallace followed in the footsteps of frustrated gamers everywhere when he ragequit during a race. (His race sponsor subsequently dropped him.) As Earnhardt remarked when asked about Wallace’s nationally televised tantrum, “I’ve seen a lot of friendships get lost either playing Madden or racing online.”

Facebook group member Patrick Garza is a racing fan who hadn’t dabbled in racing esports until “real” races went away. “I’d been aware of F1 drivers having Twitch channels but hadn’t really sat down and watched their streams, or the official F1 esports races, until the pandemic,” Garza says. He’s found the spectator experience to be similar so far, and he plans to keep watching after physical races resume. “I don’t think I’ll watch week to week as I am now, but on weekends where there are no races, I’ll most likely try to catch something.”

If a resemblance to familiar sports isn’t enough to entice bereft traditional-sports fans to try esports, the lure of money might. According to Pat Morrow, head oddsmaker for online sportsbook Bovada, the amount of money wagered on esports at the site was up almost 60 percent in the first two weeks of March and almost 90 percent in the last two weeks of March, compared to the same periods last year. The suite of esports available has also expanded. Last March, Bovada accepted action on 68 esports leagues. By this March, that total had climbed to 116, with 31—from Rainbow Six Siege’s Russian Major League and Dota 2’s China Development League to pro competitions in FIFA and Pro Evolution Soccer—added since most non-esports stopped. Oscar Brenes, head oddsmaker at online sportsbook BetCris, says his site has seen a 700 percent increase in betting volume for CS:GO leagues, a 600 percent increase in betting volume for Dota 2 leagues, and a 350 percent increase in betting volume for League of Legends leagues relative to this time in 2019.

Chris Power, a Facebook group member and dedicated daily fantasy player, is one of the recreational gamblers who’s recently trained his attention on esports. “Anything I bet on I try to watch,” Power says, adding that the exposure has imparted a newfound respect for competitive gaming. “I knew it had grown larger over the past few years,” Power says. “But watching streams and seeing a level of play I can’t do, seeing the websites and detail that’s gone into it, has definitely changed my perspective.”

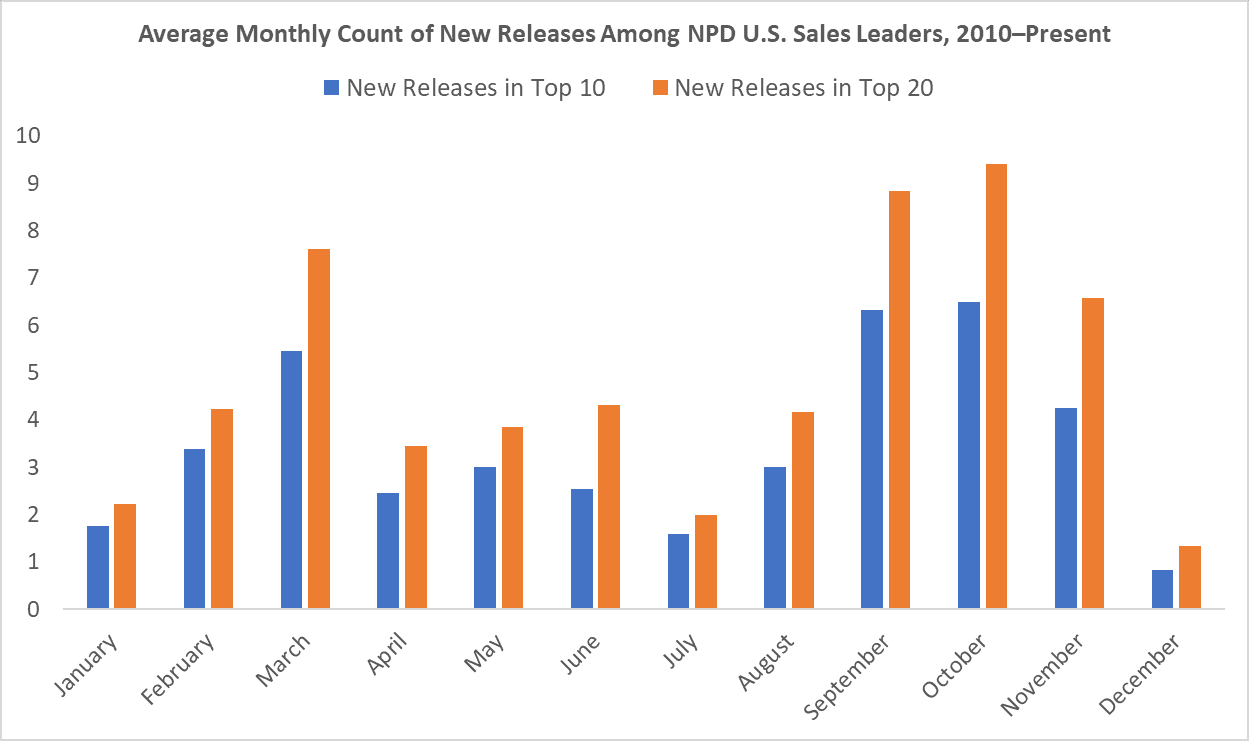

When the OWL’s Dallas Fuel kicked off their season in front of a capacity crowd at Esports Stadium Arlington in February, they played on a stage that looked like this …

… and gazed at a vista that looked like this.

When the Fuel resumed play last month, support player Jonathan “HarryHook” Tejedor Rua’s setup exemplified the league’s much more modest mid-pandemic surroundings.

That shift has been jarring in more than one way, although leagues like the OWL are better positioned to swallow the loss of ticket sales than traditional-sports leagues that have always racked up that revenue. “As most sponsorship deals and media buys occurred before the outbreak, we do not expect a tangible impact on revenues from sponsorship and media rights,” says Remer Rietkerk, head of esports for games and esports analytics company Newzoo. “Still, we anticipate a reduction in both merchandise and ticketing revenue streams, due to fewer events taking place, a general concern around attending public events, and complications regarding rescheduling.”

Vlastelica confirms that the format change has hurt teams’ bottom lines, explaining, “The teams do depend on ticketing revenue and the related revenue around those events in order to build their local businesses,” but he concedes that the impact “is a little bit less than it might be for a traditional sport.” (The Fuel had already lowered ticket prices before their remaining home stands were wiped away.) As Spector points out, though, “Running different shows around the world with the entire broadcast team working from their own homes instead of being able to come into a production facility, and the players themselves competing, in many cases, from their own homes, those were all challenges.” OWL streams matches in several languages, and its pro players are scattered across three continents.

Spector says the OWL has helped its players protect themselves by retaining the services of a group of doctors who have advised other U.S.–based pro sports leagues. Those doctors are available to OWL personnel on a confidential basis. Thus far, only Paris Eternal tank Eoghan “Smex” O’Neill—who was away from the team amid other health issues—has publicly acknowledged contracting COVID-19.

To help clear the technical hurdles inherent in a remote operation, the league has shipped webcams to players who needed them, installed software to troubleshoot remotely, tested players’ internet speeds extensively, and added strategically located cloud servers to minimize lag. It’s also rearranged the schedule to minimize head-to-head battles between distant teams. “You won’t see a team that’s based in L.A. playing a team that’s based in Shanghai, because from a connection perspective and a latency perspective, we don’t think that that’s a quality matchup,” Spector says.

Just as the cancelation of classes and concerts has inspired experimental uses of streaming—including Twitch lectures, remote record releases, and livestreamed sets—the OWL’s broadcasts have adapted their tone to the times. Although the first remote broadcasts had hiccups, fans seemed to respond to a less flashy look. “When we’re restricted in what we can do, we’re starting to think of quality a little differently,” Vlastelica says. “It’s not so much about what’s the resolution of the camera. It’s about how good is the idea and how strong is the personality and how good is the storytelling, and how resonant is our approach with the audience.”

OWL commentator Matt “Mr. X” Morello is still adjusting to a lower-energy atmosphere and a sense of separation from his fellow casters and the crowd. “Crowd interaction at the home stands was amazing, and I don’t exactly have that in my second bedroom,” he says. But he likes the looser, laid-back vibe, despite the potential for interruptions. “I also have to now worry about my dog barking during a show, which is something I never thought I’d need to consider,” he says.

As millions of Americans have learned while working from home, dog and cat cameos are often welcome on work calls. On the OWL’s first weekend back, Blizzard broadcaster Salome “Soe” Gschwind tasked her cat, Nori, with handling the hero ban phase of the broadcast, and to fans’ delight, Nori obliged by banning divisive hero Mei. “Everyone understood that somebody was at home with their cat, and so why not take advantage?” Vlastelica says. “Why not make that an element of the program as opposed to trying to pretend it’s not the reality right now?”

The OWL still plans to play in person next season, and Vlastelica and his colleagues are too attached to traditional sports to hope that esports’ time in the spotlight lasts long. Prior to joining Activision Blizzard, Vlastelica worked on mainstream sports content at FOX Sports and Yardbarker. Spector and CDL commissioner Johanna Faries are veterans of the NBA and NFL offices, respectively. “I love sports,” Vlastelica says. “I miss sports. I wish no league had to cancel any events or matches. And so it doesn’t feel great that we’re the only one that’s still going. But it does feel great to know that we can bring our fans this entertainment now, in particular, when they need it.” If traditional sports are missing much longer, those leagues’ loyalists could discover that they need esports too. They just might not have known it till now.