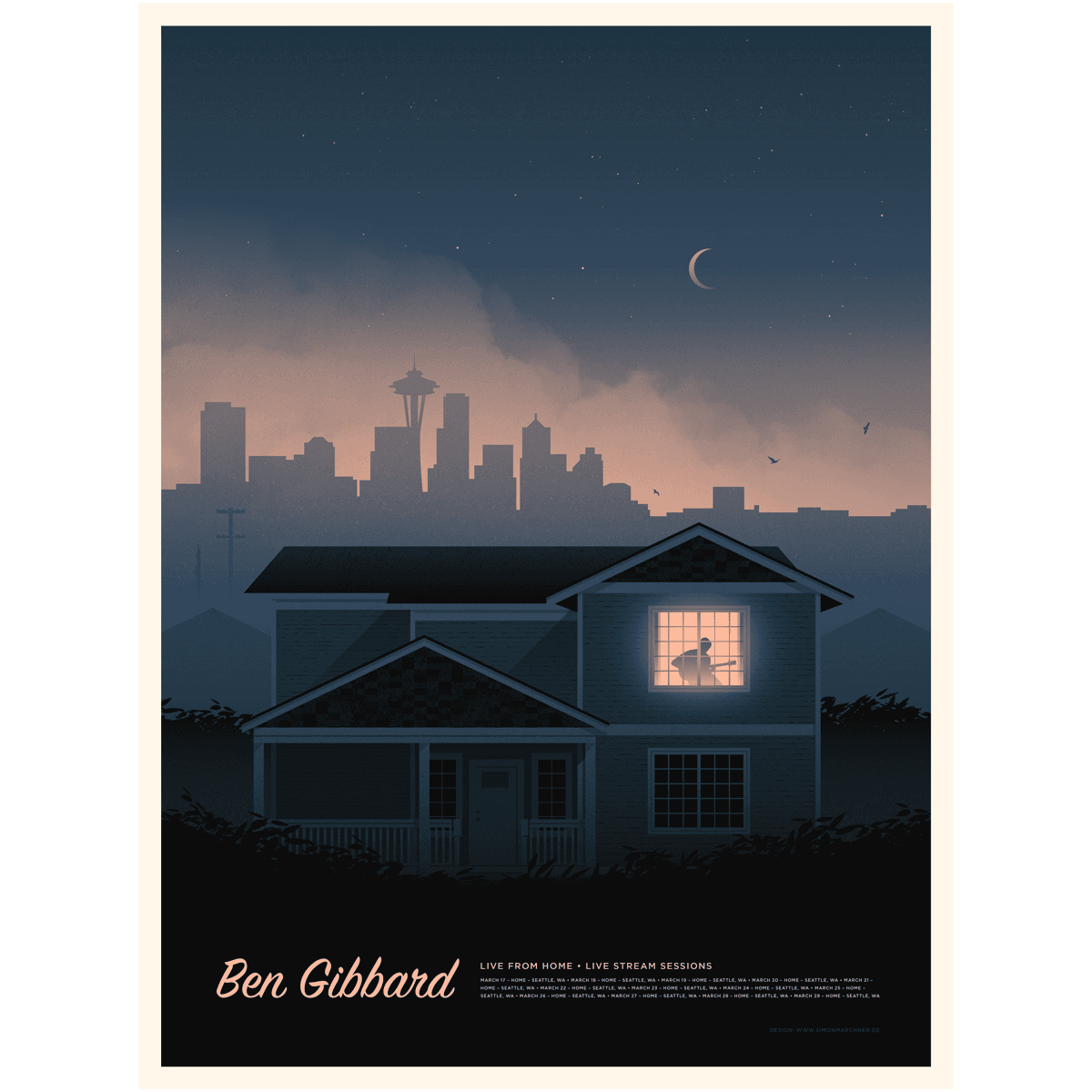

One month ago today, before most of the country started to self-isolate, Death Cab for Cutie founder and frontman Ben Gibbard stood on stage with his band at Innings Festival in Tempe, Arizona. Four songs into his set, he was forced to cut the concert short because of an illness that had first laid him low in late February. Gibbard hasn’t performed in person since then, but he’s been busy since he holed up in his home in Seattle last month. Rather than concede that this place is a prison, he became one of the first major musicians to start livestreaming concerts for charity via YouTube, Facebook, and (later) Twitch. Last week, he also released a topical tune, “Life in Quarantine.” Net proceeds from the sale of the song and the poster that commemorates his streaming series will be donated to Seattle-area relief organizations.

Gibbard, who famously collaborated long distance with his partners in The Postal Service, started his first “Live From Home” stream on March 17 with the Postal Service song “We Will Become Silhouettes,” which begins with a pandemic-appropriate verse: “I’ve got a cupboard with cans of food / Filtered water and pictures of you / And I’m not coming out until this is all over.” He reappeared at 4:00 p.m. PT on each of the next 12 days to perform for 45 minutes to an hour, taking questions and requests from viewers and working his way through his Death Cab, Postal Service, and solo songbooks. He also played a couple of all-covers concerts, in which he put his spin on the songs of musical legends like John Lennon (“Isolation”) and Tim Robinson (“Bones” from I Think You Should Leave).

Gibbard’s streak of consecutive concerts came to a close on Sunday, but he’ll still be streaming weekly on Thursdays at 6:00 p.m. PT for as long as we’re all getting no sunlight and trying to laugh indoors. We called him this week to ask how livestreaming compares to performing in person, concerts as quarantine therapy, whether streaming could replace or supplement touring in a post-quarantine world, revisiting the Death Cab catalog, and his feelings about bidets.

It’s actually only been about a month since you were last on stage, albeit briefly. I’m guessing it feels a lot longer than that.

It really does. This hasn’t been going on that long, all things considered. But it feels almost like a lifetime ago that things were normal. Maybe that’s just a testament to how great we had it. Even the things we complain about on a daily basis with politics and stupid internet shit that doesn’t matter and weird feuds between celebrities and stuff that people felt were important.

You got sick at the end of February. How long did it linger to the point that you were kind of incapacitated?

Maybe at some point, when there is a viable test for antibodies, I will know if I had coronavirus or not. I made a little post about it and pulled it down pretty much immediately because I felt it was unfair to speculate about it. But I had a dry cough and then for four days I had rolling fevers upwards of 101, 102. And by the fourth day, I was having anxiety attacks and was convinced I was dying. It was really scary. The show that I attempted to play, I got back to the hotel and my fever spiked and I had to have Nick, our bass player, and our tour manager come in and literally ice my body down because my temperature was continuing to go up.

That’s the first time I’ve ever had to have that done, and that felt really scary. And I didn’t have any of the acute respiratory distress that people have been talking about with this. But my understanding is there are different tiers of COVID-19, and I have a friend who is a really strong ultra runner who got the full-meal-deal COVID-19 in mid-February, with the shortness of breath and not being able to walk a half mile. And this is a guy who runs a 16-hour 100-miler, which is very fast, and is a very fit 35-year-old. So I think that this has been in the country a lot longer than we think it has been. I’ve read other accounts of people who tested positive who had very similar symptoms and timeline to me. But there’s no way of knowing until there’s a test for the antibodies. So at this point I’m going to treat it like I haven’t had it and not get cavalier with my activities and proximity to other human beings.

Did you have any misgivings about doing the live shows while you were still dealing with a cough? Just because everyone was seemingly so worried about you every time you would talk.

Yeah. It was also exacerbated because I have this compression on the microphone, so what sounds like a terrible cough on a compressed u87 does not sound as bad in the room. But I had health care professionals contacting me. I had a couple of doctors who are friends of my parents being like, “He really needs to get the test. He definitely has it.” And I’m like, “Guys, I’m not running a fever.” Like, if I had a fever and this, I would be looking to get tested in some capacity. But even if I had wanted to get tested, it’s not like the tests were available. And if I came down with something tomorrow, God forbid, I certainly wouldn’t run right to the emergency room like so many people are doing, which is exacerbating the problem and overloading the health care system for people who are falling into acute respiratory distress as a result of this thing.

Had you done any previous livestreaming?

I’d never done it before. Obviously we have shows that are broadcast live on the internet, because that’s a part of living in the 21st century. But I have never done anything like this before, and I have to admit, I was maybe a little bit reticent to do it. Just because I think for people of my generation who didn’t come of age in front of a screen, didn’t come of age with social media and creating YouTube channels from high school on, it felt rather intimidating, and I didn’t particularly know how people were going to react to me. And having people commenting in real time felt like a terrifying prospect. But because people were so grateful for any respite from the news and being anxious and terrified—I don’t think people would be cruel if this had not been the case, but in this particular case, people are just very grateful for any break from being worried all the time.

The Postal Service was sort of social distancing decades ago. I guess that experience prepared you for making music remotely.

Yeah. In this era, there are so many acts and bands that do not live in the same city and make music just via Dropbox and WeTransfer. It’s an incredibly easy way of doing things now. And I suppose in 2001, 2002, when we were making Give Up, the technology was technically there that we could have sent some things back and forth, but it certainly wasn’t in the place where it got to even five years later. So Jimmy [Tamborello] would call me or email me and tell me he was sending a CD-R of some new instrumentals. And then I would get it in the mail and then put it into my computer and work from there.

The last time I saw you perform, it was a big production with the full band and a fancy light show and coordinated outfits—quite a contrast to you sitting by yourself in a small room. But streaming seemed like a different kind of communal experience. When you’re streaming, you don’t get to see the audience the way you would at a live show, but you get reactions and questions in real time, and you interact more than you would with standard stage banter. Did it feel interactive in a way that a live show doesn’t?

It really did. The first couple of shows I referenced my friend Dave Bazan, who will in the middle of a show ask if anybody has any questions, and it’s one of his signature moves at his shows. So I was calling it the Dave Bazan honorary Q&A or something like that. And when you’re at a show and people are yelling questions at you in tuning breaks or yelling requests, I usually choose to not interact with that because then it becomes an avalanche. If one person sees it work, then everybody else thinks it’s going to work too, and then the show can go off the rails.

But in this particular format, it was really nice to say, “OK, I’m going to take questions after the next song,” and then all these questions come in and I’m able to choose the question that I want to answer rather than having somebody yell out, “Do you still talk to Zooey?” or something like that. It’s easy to manage the tone of the questions. I think the largest crowd I’ve ever pulled on my own at a solo show might be the Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco, which I think was 1,800 or 1,900 people. But certainly on the first show, because it was the first one, we had I think almost 20,000 people watching, and we were averaging between 8-10,000 people a day watching the show.

And so to think of what that number of people would look like—I mean, that would be like a scaled-down arena every night. Which of course the band can’t do, let alone me doing a solo. So once I thought about it in those terms, it became its own stand-alone experience that’s obviously very different from playing a show with a live audience. But I think one thing I really liked about it is that it offers an intimate experience for a very large number of viewers. It doesn’t come with any of the impersonal elements that naturally come when you play to a larger audience.

Did you get any of the pre-show jitters or adrenaline rush that you would with an in-person appearance?

Oh, 100 percent. The first show, I was pacing down in our kitchen, and Rachel, my wife, said, “Oh yeah, you’re pacing like you’re going on stage.” And I’m like, “Well, I guess I kind of am going on stage.” Especially on the first show, I felt nervous in the same way I felt right before I went on stage at Thalia Hall in Chicago in January. And over the course of the last couple of weeks, having this show at an atypical time for me to be playing in front of an audience—playing at 4:00 p.m. as opposed to 9:00 p.m., which is usually when I play—that was a strange element of it as well. Because I’d finish a show and I’d be amped up from having performed and having had to be on in front of people, and then it’s like, “Oh, what are we making for dinner?” It’s a very strange readjustment of my purpose from being an entertainer to helping my wife pick the cilantro for dinner.

How much prep time did you put in for each 50-ish-minute show, factoring in the song selection and rehearsing and whatever private soundcheck you did before you went live?

I would say probably about an hour and a half. The cover shows took a little bit longer because I wanted to get the songs in before Saturday so I could spend some time practicing them. And I had cheat sheets up on the computer. I would have the lyrics and some chord changes for songs I didn’t know as well as others. At the bare minimum I would be in my studio at 3:00 rehearsing and just getting the set together, making sure I had people’s Instagram handles alongside the songs that people chose, and made sure the charitable component was all worked out.

But there was a day last week where I had a musical project I needed to work on up to about a half hour before I went on, and it was very jarring to go from being there recording and working on this other thing to getting into show mode within a half hour. It would be the same as if I was on tour and we were in a recording studio until 8:00 p.m. and then we had to go over to play the gig. It’s one of the reasons that I’m not particularly creative—I don’t write hardly at all—on tour, because the show is the focus of the day and I need to make sure that I’m preserving the mental energy and that I can draw on that focus to be in front of an audience. And I found it very similar even doing the shows at home.

Based on the number of views on the YouTube videos, it seems like more people have watched the shows after you finished than were watching live.

Yeah. And it was cool to see this small little community form around the show. I started to see a lot of the same handles every day, and people talking with each other. Before the show I’d open up the broadcast window, and I would see people in there talking, like “Oh man, what’s he going to play today?” Or “How was your day today? Where are you again?” Which obviously is a part of every message board and every online community ever. But I had never seen that coalesce directly around something I was doing in real time, which was very cool.

Did you hear from anyone for whom the show became a therapeutic thing?

I got a lot of messages in the last couple of days especially, people who were very grateful for the shows occurring, and people had individual stories. To try to pull one out would kind of sound like a preacher telling a story at the pulpit to prove a point, you know? I recognize and I’m very grateful that people turn to these shows for a break from the craziness and for solace and to have something else to think about for a while. And to join a community around something that they enjoyed.

This is also really therapeutic for me. I certainly set out with the purpose of having this altruistic component to it. But this is also really valuable to me to have a focus of my day every day, where I was accomplishing something by performing. And my life is kind of split into two halves with my music. There’s the being at home trying to write stuff, sometimes successfully but more times than not unsuccessfully. And that comes without a schedule. It comes without expectations. It’s sometimes very fruitful; other times, it’s completely not. And I go weeks being very frustrated with my ability to accomplish what I’m trying to accomplish.

But when it comes to doing shows or being on tour, I have to be on stage at this time, and I have to play for this long, and I need to be in a good mood, because people are either paying for this or they are investing an hour of their life into this and they deserve a break from worrying about dying, so they deserve that. And you have entered a social contract with them that you will provide that for them. So the show gave me an unbelievable sense of purpose, especially in the early days of this lockdown, when there was all this talk of quarantines on a level that we have yet to see—you know, the ferries are going to stop running, the National Guard’s coming in and holding everybody in their houses, all of these rumors. And people were starting to send those texts that I’m sure you got as well, which are like, “Hey, I’ve got a friend who has a cousin in the CIA.” And it’s like, “Yeah, they say that they’re going to start taking every couple’s firstborn child. Starting at 6:00 a.m. they’re coming in your house.” That kind of crazy rumor stuff. And so I committed to this run of shows at that point as much because I felt I needed something in my life that would ground me.

At what point did you decide that you were going to keep it going weekly beyond the initial run of shows?

I realized that doing it every day was going to be unsustainable at some point, if only because I do have other things I need to accomplish right now. I have not only a record to write, but I also have a couple of other musical projects that are in the gestation phase that I need to dedicate some time to. And also just doing these shows at a particular time every day—I think the last time I did 12 shows in a row was in 1999 or something. I mean, it was back in the van days where it was either play or starve. So I never do more than three, maybe four shows in a row with the band, just because my voice can’t handle it. Of course we’re playing longer, and it’s a more energetic show.

But I decided that I wanted to continue to do at least one show a week throughout the period of quarantine—as I said, as much for myself, because I enjoy doing it and it grounds me in a particular way. But also because this is something that people who are fans of mine and of the band and of the Postal Service—it was very clear that some people were very sad this was not going to be a part of their day anymore. And that’s an odd thing for me to say out loud. But I felt I had signed a particular social contract that I couldn’t just be a part of everybody’s life every day and then just disappear into the ether until we’re promoting another record or something. So it felt like the right thing to do. It’s like, let’s do one a week. That way we can focus the charitable component a little bit better. We can have a little time to set it up.

I think I got into a good rhythm in the second week of these, but it would have been incredibly difficult to continue to do interesting and unique sets, because I was starting to run out of songs. I had a couple of days, maybe, that I could have pulled out some more stuff. But I didn’t repeat myself that often, and that was by design. But I also didn’t want to just keep doing these things until nobody was watching. The band, we’ve had this joke idea for years that we should just set up at a club and we’ll do a residency until nobody shows up. So we will play every day until nobody shows up. And I didn’t quite want to subject myself to that either, where it’s just 50 superfans who were asking me to play more and more obscure tunes because they’ve heard everything.

You mentioned on the streams that you gained a greater appreciation for some songs you played that have fallen out of your setlists lately. How much will that affect your future song selection?

It’s been quite eye-opening to re-interface with some of these songs that I had not thought about in 15 years. We have so many songs at this point—and this is a good problem to have—but we have at least 10 to 15 songs that if we do not play them, people are going to be angry. And because I consider myself first and foremost an entertainer when we’re on tour, I feel an obligation to play the hits every night, unless the show has been billed otherwise. We’ve all gone to shows where you go to see your favorite band, you’ve had the tickets tacked up on the fridge, or now, probably, you’ve got it in your phone or wherever. And you’re looking at it, you’re excited. And then they act like they are above the songs that they made that got you in the door in the first place. I just find that to be incredibly insulting to an audience. I’ve been in the audience at those shows before.

So I have found that there are songs throughout the catalog that I liked, but because so much of our fan base, just by the numbers, came on with Transatlanticism and Plans and Narrow Stairs—that was obviously our high-water mark as far as our cultural zeitgeist moment, the style of music we were playing and other bands that were like us. So people know that stuff really well. But it’s been amazing to see, not just one person, but dozens of people asking for some songs that I hadn’t thought about in forever.

And it’s been nice to realize, as I went through the different eras of the band and did those sets, to see that, “OK, well, maybe a lot of these deep cuts, people are actually listening to these records more than I thought they were listening to them.” Maybe because in a streaming economy now you just assume people listen to the songs they like and they don’t dig as deep into albums as maybe we did when we were younger, because we bought them and then we had to get our money’s worth of enjoyment out of the album. I just assumed that a lot of these deeper cuts were falling by the wayside. So it was interesting to see people asking for those, and then when I did play them, seeing people just really freaking out that I was playing some of these tunes that I didn’t think anybody cared about.

If you can stay where you are and work the way you want to work and still find an audience this way, is streaming something you could envision doing instead of a tour when the world hopefully returns to normal? Or is this just a weird pandemic-specific experiment?

I think it’s probably the latter. I still really value being in front of actual people. Well, I guess there are actual people watching the stream, but being in the physical presence of other human beings. Only time will tell, but I have to believe for the sake of my career, honestly—because live music is really one of the last reliable or somewhat reliable revenue streams for bands these days—that nothing will ever compare with being at a show with other people. But I guess we’ll see how good virtual reality technology gets. If you’re wearing a suit that makes it feel like you’re crunched up with other people and something’s pumping in the smell of stale beer and cigarette smoke, maybe we don’t have to go anywhere.

At this particular juncture, I would find it rather gauche to charge for this, which would be the way I would do it. If you were not going to go on tour, you’d have to figure out a way to say, “OK, it’s $5, and you PayPal and then you get a code.” But I would hope that when the world gets back to as much of a normal as we can get back to, people are going to want to be out with other human beings. Nothing will compare with being in a room with your favorite band playing loud, with the lights going, and smoking a doob with your friends and just having a great time. And going off into the night and going to a diner afterwards and talking about the show, or going to a bar. And I don’t think you’re going to see a surge of people charging for virtual concerts. I think that people doing this kind of thing at this moment, this is kind of a musical triage. This is just a way to provide any connection with other humans in a situation as it is today, where we are all stuck in our homes. I mean, I have a weekly FaceTime with my entire family. We normally would get dinner together, and we’re just, “Oh, it’s 7:30 on Sunday.” We all open up the computer and talk to each other, and yes, it’s nice to see a real face. But I’d much rather be at my parents’ house.

Was “Life in Quarantine” a tune you had hanging around already and decided to adapt, or was it something you wrote fresh?

I wrote it fresh. I wrote it—I’m losing track of time, but in the first week that we were home. And as I tend to do, I will exaggerate for dramatic effect, but with the exception of the National Guard, everything in that song has occurred today, and we might see the National Guard at some point. I had friends who were trying to get home at airports, and it was just people telling me stories about people getting in screaming matches with gate agents about why they needed to be on the plane or why isn’t the plane taking off, or it’s just people starting to lose their minds a bit.

I would say probably before we got into official “stay inside” directives and before the bars were closed and the restaurants were closed, I was joking with somebody about like, “Oh man, this is like old Seattle. I mean, I got from Queen Anne to Capitol Hill in 10 minutes at 5:00 p.m. on a Friday, this is great.” And joking about that kind of stuff became very insensitive and not cool pretty quickly. And I think that everybody that I know, if it didn’t happen that week, certainly in the last two weeks, everybody I know has had a moment of “Holy shit, this is very real. I cannot cheat the system. I thought A, B, and C didn’t really apply to me.” Everybody that I know has had that realization like “Yeah, no, this is very real, and this 100 percent applies to me, and I’m just going to fall in line and do what I’ve got to do.”

And how did you decide to cover “Bones”? Popular request, or personal favorite?

A personal fave. I’ve watched that series a gajillion times at this point. But it was also a much-referenced joke on the DCFC tour. I might be talking about a song I’m working on, and a crew or band member would chime in with “What about something that goes like … ‘The bones are their MONEY …’”

I guess it would be impossible to tell precisely, but do you have any sense of how much was raised for the causes you supported?

I can’t give a number, but one story I can tell that’s been really heartening is there’s an organization called Aurora Commons that Rachel and I have been supporters of for a long time, and we’re friends with the people who run it. And it’s ostensibly a safe space for people who are temporarily experiencing homelessness on Aurora Avenue here in Seattle, which is kind of a rough area of town—a lot of sex workers, IV drug addicts, and the like—and it’s a place where people can just go in and make food, or do the laundry, or my friend Lisa will take them to their STD test or their job interview or wherever it might be. And because so many of the shelters on the North End have been closed because of COVID-19, and all the hotels are full, and there are no allowable camping areas on the North End, a lot of these people are literally left with nowhere to go. So while it’s not a great solution, there was a call out to collect as many tents and sleeping bags as people could give for the purpose of handing them out to people who were going to have to spend the night in the street.

And after I made the plea on The Stranger and we did the episode where we discussed it, we literally gave them Lisa’s address and just said, ‘Drop this stuff off on the front porch. You don’t have to go inside, just drop it off on the front porch and knock and then just walk away.’ And they filled three pickup trucks full of tents and sleeping bags that people who had either seen my thing on The Stranger or who were watching the livestream had gone and dropped off. There was a food bank in White Center that saw $2,000 in donations come in within 24 hours from people who were watching the stream.

It’s been my belief, certainly in the early stage of this, that we are in a very sweet spot right now where people are wanting to be altruistic and they recognize that people are suffering and they want to do something to help their fellow human beings out. And if people do not have money to give, they might have a tent or extra can of beans or something that they could drop off at a food bank as “payment” for the show I just played. But what I’m fearful of is, the longer this goes on, I think, human beings have a tendency to batten down the hatches and create a smaller circle. Eventually they are less willing to help people they don’t know. So this is, I think, an incredibly important time for people who are doing this kind of work. This is the time where they can really accrue resources, be they material things or financial donations, because people are willing to do that right now. They understand the need.

Streaming seems to have been a virtuous circle.

Yeah, I was imagining at some point doing these shows that somewhere out in the world—and this tends to be a demographic breakdown of some of our fans, maybe the woman in the relationship is a big fan but the guy really doesn’t like our music at all. Over the years I’ve gotten a lot of “Oh yeah, my girlfriend loves you guys,” or “Yeah, my wife loves you guys,” and I’ve seen a lot of women really enjoying the set next to somebody who had their arms crossed and was like, “I have to be here. I don’t want to be here. I hate this band.” And I was just imagining there’s probably a number of couples who are quarantined together right now, and one of them is insisting on watching this show every day to the great lament of their partner. And I just thought that’s really funny to me, because I’ve seen that at our shows, but that’s like two hours once. This is an hour every day for 12 days. And then maybe once a week as well, if they can negotiate that.

Lastly, in this time of toilet-paper shortages, will you join me in publicly endorsing the bidet?

I can unequivocally endorse the bidet. Rachel got one for me—well, technically us—this past Christmas, and it has been a game changer. Needless to say, we are not worried about running out of TP over here.