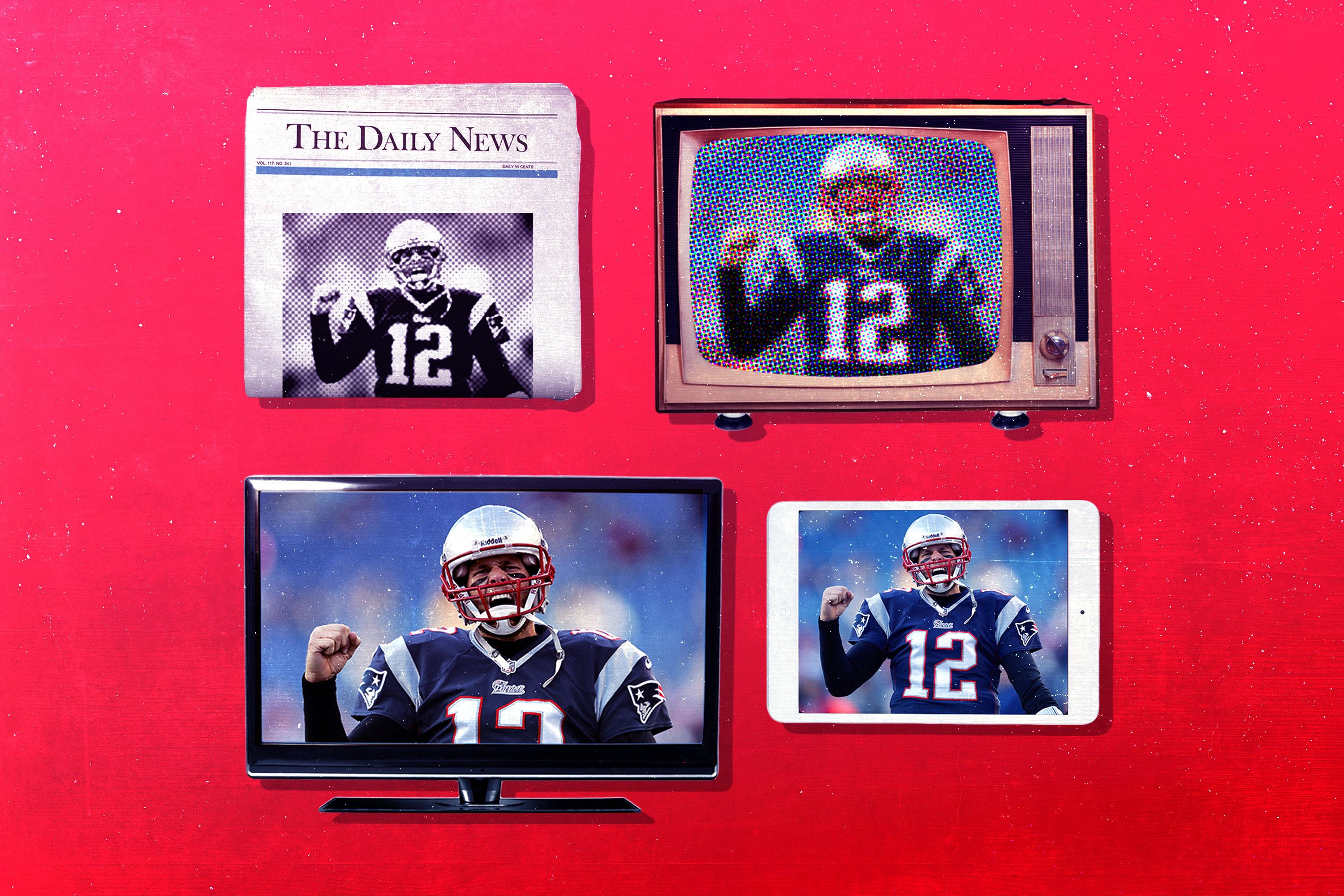

Editor’s note: Tom Brady officially announced his retirement from the NFL on Tuesday. As the football world remembers his colossal legacy, we’re recirculating this piece.

When Tom Brady decided to sign with Tampa Bay, it was a blow to one of history’s greatest dynasties. Not the Patriots—their press corps. For the last 20 years, writing about the Patriots has been the most efficient way to get a great job in the sports media. You’d have to go back to the old Yankee Stadium press box to find a group that has enriched itself more thoroughly with national jobs, book deals, and general career enhancement. There have been choice beats before. Which one of them could bless the careers of both Dave Portnoy and David Halberstam?

Bill Belichick’s sportswriting tree has fared way better than his coaching tree. Writers whose careers were improved and/or made by writing about the Pats include Ian Rapoport, Michael Smith, Albert Breer, Tom E. Curran, Mike Reiss, Greg Bedard, Michael Holley, Ben Volin, and—let’s not forget—Bill Simmons.

The Patriots added volumes to the bookshelves of Halberstam, Ian O’Connor, Charles P. Pierce, and New York Times Magazine political writer Mark Leibovich. They added to the oeuvre of filmmakers like Tom vs. Time’s Gotham Chopra, and Geno McDermott, director of the Aaron Hernandez Netflix series.

Patriots scandals and palace intrigues have been grist for writers like Seth Wickersham and Don Van Natta Jr., The Athletic’s Bob Kravitz, and Jeff Darlington, who insisted for months that Brady was prepared to leave New England. Rodney Harrison (former Pats safety) and Field Yates (former Pats intern) have roosted in TV jobs alongside many of their colleagues. Plus, daily Pats news feeds Globe columnists, local sports radio hosts, and the Sarlacc pit of Barstool.

“You want to want to remain as objective as you can when you’re writing about it,” said Curran, the Patriots insider at NBC Sports Boston. “In my estimation, you still have to have in the back of your mind, You’re so fucking lucky. You’re so lucky you just happened to be in the right place at the right time.”

Curran’s career arc is instructive. As he’s fond of saying, he didn’t “make his age” in journalism until he was 35 years old and covering the Patriots for the MetroWest Daily News in Framingham, Massachusetts.

“At that point, I’d been in the business 11 years with three boys all under 3,” he said. “I didn’t know if I could keep doing the work anymore because I wasn’t making enough money. … I was actually talking to people about selling field turf.”

In 2002, while Curran was covering the Patriots’ first Super Bowl win, in New Orleans, a writer tapped him on the shoulder and told him he was going to be hired by the Providence Journal. Four years later, Curran moved to NBC. By then, Patriots writing was a growth industry. Curran went from thinking about leaving journalism to writing Julian Edelman’s memoirs.

“You didn’t have to go to Slippery Rock and work in TV,” he said. “You didn’t have to go to Anchorage and work at a paper. You could just stay right where the fuck you were and have this happen around you.”

Sportswriters would like to think their work will get attention whether they’re covering the Patriots or the Jaguars. But the clearest path to career advancement is to cover a dynasty. That’s why national outlets’ rosters are filled with talking heads who covered the Warriors, the ’90s and ’00s Yankees, and the ’90s Cowboys.

Hiring a writer off the Patriots beat is a bonus for a national outlet. It offers the outlet a chance to compete on the stories that were going to dominate their headlines anyway. On Tuesday, when the NFL Network’s Rapoport reported that Brady had a contract with Tampa Bay that would pay him as much as $30 million per year, he was completing the life cycle of a former Patriots beat writer.

When a reporter covers a normal sports dynasty, he might get five years to earn promotions and a book deal. The Patriots’ dynasty has lasted nearly four times that long. The team won its first Super Bowl a few months after the September 11 attacks and waved goodbye to Brady as the coronavirus spread across America. In terms of longevity, Curran noted, he has covered the rough equivalent of Bill Walsh and Vince Lombardi’s careers combined.

You didn’t have to go to Anchorage and work at a paper. You could just stay right where the fuck you were and have this happen around you.NBC Sports Boston reporter Tom E. Curran

You can see generational change on the Pats beat. Michael Smith, who later became a host at ESPN, was just 22 years old when he became the Globe’s backup beat writer in 2001. The Patriots dynasty also spans an epoch of media time, before sportswriting was fully nationalized.

“How were people going to get news on the Patriots in ’01, ’03, ’04 on a day-to-day basis?” said Curran. “They weren’t going to have their national reporters there, they weren’t going to have ESPN there on a daily basis. … They had to get it from us.” That, in turn, led to more promotions.

Beyond piling up titles, the Patriots proved to be a rich subject for writers. The troika of Brady, Belichick, and Robert Kraft didn’t have nearly the comic potential of Reggie Jackson, Billy Martin, and George Steinbrenner. But they had their upsides.

Kraft is an ideal owner to cover because he’s incredibly needy. (On Tuesday, he was telling reporters of Brady, “I love him like a son.”) Brady can be purposefully bland, but the scandals he has been involved in—or, as he tells it, have been thrust upon him—give him a kind of texture.

“The villain is always far more compelling than the guy who is Mr. Perfect,” said Leibovich, who interviewed Brady for his book Big Game. “That’s why, in a weird, paradoxical way, Brady made such a great villain.”

Belichick may stiff-arm beat writers and even the league’s cherished TV partners. But his remoteness has created its own alternate content stream. I can’t think of another NFL coach whose leisure photos would be a thing, maybe outside of Andy Reid.

The ’90s Cowboys used to be the record holder for extracurricular activities, real and alleged, which produced mountains of journalism. The Patriots took the lead with Spygate, Deflategate, Kraft’s solicitation charges, and the Aaron Hernandez murder trial. For another franchise, Belichick’s endorsement of Donald Trump would have been a nuclear event. With the Pats, it almost gets lost.

Thanks partly to such quagmires, Patriots coverage came to mimic, or maybe anticipate, the contours of political coverage. You’re pro-Pats. Or—the pro-Pats people say—you’re anti-Pats. This creates yet another meta layer of content, as Darlington, Chris Mortensen, Sports Illustrated’s Charlotte Wilder, and anyone who has been lit up on a Boston sports radio show can attest.

There’s an irony to the Patriots beat being a career-maker. Teams like the Warriors and Cowboys laid out the welcome mat for reporters. Covering the Patriots is more of a chore, as if enduring those “on to Cincinnati” answers is the price of fame. “Social distancing is basically the Patriot Way placed onto society,” said Leibovich.

Even with Brady gone, it’s not like the Patriots beat will fade into obscurity. “Was Brady or Belichick the Real Genius?” will be an ESPN chyron into the next presidential administration, provided debate shows are still being produced. Belichick powering an Andy Dalton–led team into the Super Bowl could produce another coverage boomlet.

But in the meantime, the Patriots press corps will have to share its good fortune with some star-crossed counterparts. If there’s any life left in Brady’s 42-year-old arm, you can go ahead and congratulate Rick Stroud on his book deal right now.