In late August 2018, the second-place Oakland Athletics visited Houston for a potentially pivotal three-game series against the first-place Astros. The A’s entered the series boasting baseball’s best record over the previous two and a half months (45-19 since June 13), and they trailed the Astros by only 1.5 games in the AL West. The previous week, the two teams had actually spent a few days tied atop the division, although the A’s had never pulled ahead. If Oakland swept this series, the reigning world champions would be looking up at the A’s.

The A’s dropped the first game of the series 11-4, but the next two contests would each be decided by one run. Journeyman Edwin Jackson, pitching for the 13th of his record 14 franchises, took the mound for Oakland in Game 2. He also took his time. The A’s and the Astros wouldn’t face each other again during the regular season, and given their proximity in the standings and the closeness of the score, each pitch was too critical to rush. But there was one other factor extending Jackson’s pauses between pitches: The A’s were aware that the Astros might be stealing their signs.

“I knew about that two years ago, that it was going on,” Jonathan Lucroy, who caught Jackson in that August game, told ESPN last week. “I know it just recently came out. Everyone in baseball [knew], especially in that division that played against them. But we were all aware of the Astros doing those things and it was up to us to outsmart them.”

Lucroy hadn’t heard Houston’s banging when he went to Minute Maid Park in 2017, but 2017 Astro Mike Fiers had told him and his teammates about the Astros’ illicit sign-stealing strategies when he joined the A’s in early August 2018. The A’s complained to MLB about the Astros’ behavior in 2018, but MLB didn’t launch a large-scale investigation until Fiers went public last November. The league’s inactivity put the onus on the Astros’ opponents to conceal their signs.

“It was a mental workout,” Lucroy recalled, specifically citing Jackson’s start. Working with a veteran, Lucroy felt free to deploy an advanced defense against the dark arts. “We were switching signs every pitch—every single pitch—because you had to,” the catcher continued. “If you didn’t, they were going to get it and go up there and take advantage of it.”

Here’s what that effort looked like in action—or from fans’ perspective, inaction. Behold, the roughly 50-second span between pitches following a foul by Carlos Correa with two outs in the fourth inning:

Approximately 10 of those seconds came from Lucroy’s complex sign sequence alone.

Another 40 seconds elapsed before the very next pitch:

This time, Lucroy’s sign sequence lasted even longer.

Both times, Correa stepped out before the pitch was delivered, either resetting himself or attempting to disrupt Oakland’s pitcher-catcher code talking. Keep in mind that the bases were empty during this plate appearance, which means that Jackson didn’t have to feign a pickoff attempt or hold the ball for a few extra beats to disrupt a runner’s timing. According to Baseball Prospectus, the average time between pitches with the bases clear was 6.6 seconds shorter in 2018 than it was with runners on, but in this case, the waits were excruciating even without any bags being occupied. The A’s may have thought those waits were worth it: Jackson lasted only 4 2/3 innings, surrendering three runs (two earned), but Oakland beat the Astros 4-3. Beginning with their 5-4 victory in Game 3, though, the Astros went on an AL-best 22-8 run to finish in first by six games.

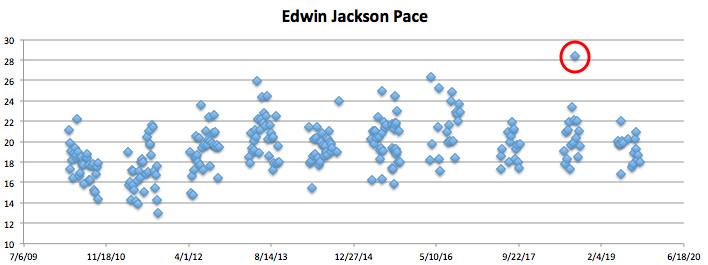

Granted, Jackson is a habitually slow worker: Per BP, he averaged 23.8 seconds between pitches in 2018, which led all pitchers who threw at least 750 pitches. (FanGraphs, which also shows Jackson leading the league, reports an even longer average time between pitches, but BP’s method discards any delays longer than one minute, presuming that a pickoff attempt, an injury, a mound visit, or something else out of the ordinary must have occurred.) Only two of his 17 starts in 2018—one of which was in Oakland—came against the Astros, so relative to most pitchers, he dawdled on other days, too. But that game at Minute Maid was an outlier even by Jackson’s standards. The righty’s 28.1-second average time between pitches with the bases empty was the longest he’s inflicted on fans in any outing dating back to 2010.

The irony is that Correa may not have had Oakland’s signs in that situation even if the A’s hadn’t taken extra precautions. MLB’s investigation into the Astros’ sign stealing found no evidence that the team utilized the trash-can-based banging scheme in 2018 (and once one knows about the banging scheme, it’s hard to hide). Commissioner Rob Manfred’s report noted that “the Astros’ replay review room staff continued, at least for part of the 2018 season, to decode signs using the live center field camera feed, and to transmit the signs to the dugout through in-person communication.” However, the commissioner concluded that the Astros ceased even that more limited method of sign stealing at some point during the 2018 regular season. What’s more, the replay-room method relied on a runner on second relaying the signs to the batter, and in his fourth-inning plate appearance, Correa wouldn’t have had that helping hand.

Of course, it’s possible that the Astros were still stealing signs in late 2018 via some pervasive, hitherto-undocumented method (insert buzzer-based conspiracy here). But by that time, at least some Astros opponents were paranoid enough to act under the assumption that the Astros were cheating, regardless of whether they still were. Jackson and Lucroy weren’t the only battery to slow down against the ’Stros; Angels starter Andrew Heaney, who recently said he hopes the Astros feel like shit, worked with catcher Francisco Arcia in two late-2018 starts in Houston and showed a similar spike in bases-empty time between pitches.

According to Lucroy, those slow-motion starts were part of a pattern in games against the Astros. “The guys were calling time and stepping out of the box as you take time to put your sign sequence down, and it was making games long and leaving guys out there,” he said. “Their system, not only did it work with them having the signs and being able to see them, but it made our guys sit out there longer. … I’m glad it’s been taken care of. It was out of hand and it affected the games in a lot of different ways.”

Lucroy’s recollection about Jackson’s start stands up to scrutiny, and other pace-based evidence supports the catcher’s contention that the Fiers-informed A’s weren’t the only rival club clued into the Astros’ rule-breaking behavior. If we treat time between pitches as a proxy for sign-stealing suspicions, it seems clear that the league as a whole had caught on by 2018.

That’s important for three reasons. First, it helps explain why the Astros may have abandoned their sign-stealing efforts when they did (according to the commissioner). Second, it illuminates a hidden cost of illegal sign stealing—longer times between pitches—that may be minor compared to concerns about competitive integrity but still seems significant amid ever-present worries about baseball’s slowing pace and lengthening games. And third, it lends credence to the idea that the Astros’ misdeeds were well known within the game long before MLB took steps to punish them, which would indicate that the league’s response was, if not necessarily too little, then at least too late.

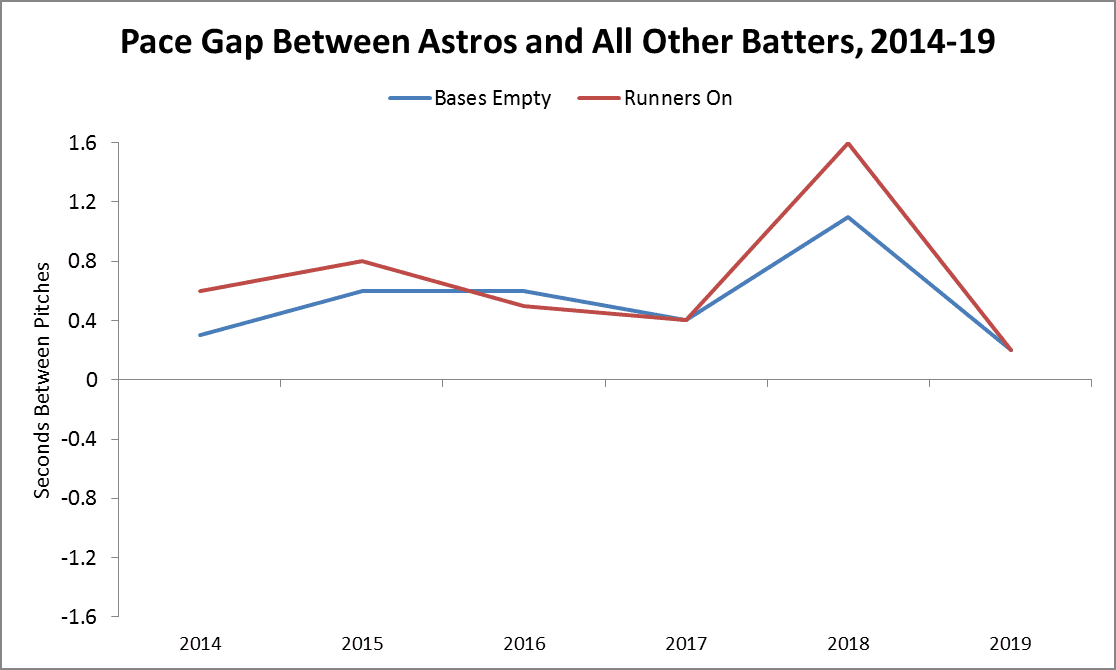

Let’s examine what BP’s pace stats suggest about the timeline of other teams trying to counter the Astros’ sign-stealing efforts. The graph below shows the annual difference between the average time between pitches against Astros batters and the average time between pitches against all other teams’ batters with the bases empty and occupied. Let’s call this the pace gap.

The Astros’ pace gap didn’t climb between 2016 and 2017, which indicates that teams didn’t immediately adjust their between-pitches routines in response to the banging scheme. That makes some sense, because the Astros didn’t fully embrace the banging until they were approaching the midpoint of the 2017 season, and it would have taken time for suspicions to circulate around the league and for teams to formulate and implement plans to combat the Astros’ bad behavior. Houston’s pace gap peaked in 2018, when the time between pitches to Astros batters was 1.6 seconds longer than it was against all other batters with runners on and 1.1 seconds longer than it was against all other batters with the bases empty. It then decreased again in 2019, whether because the Astros had stopped stealing signs illegally, because the stricter regulations and monitoring MLB had put in place that spring had assuaged some sign-stealing concerns, or because teams had also started cycling through signs against additional, non-Astros opponents.

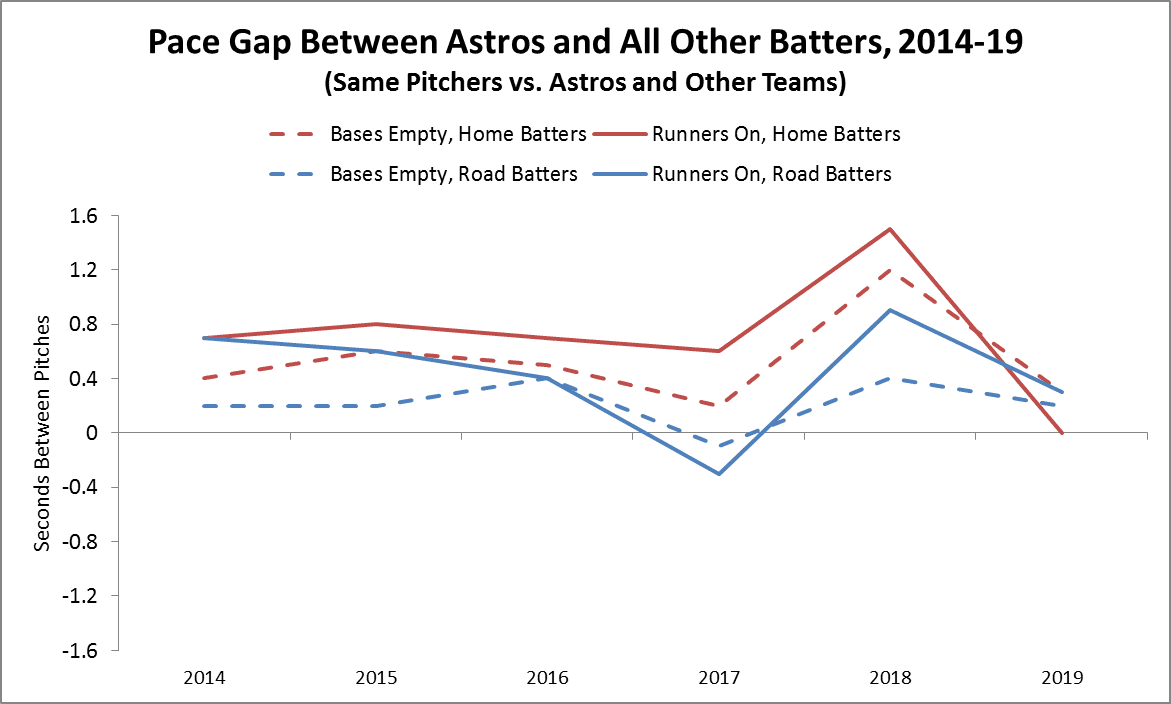

Granted, this method doesn’t account for pitcher pace tendencies. Pitchers exert more control over the time between pitches than batters do, and it’s possible that the 2018 Astros happened to face a slower-working collection of pitchers than other teams. We can account for that, though, by limiting our sample to pitchers who faced the Astros and then comparing the average pace of only those pitchers in their games against the Astros and their games against other opponents, weighted by their playing time against the Astros. When we do that, we get results so similar that I’ll spare you a second graph. Instead, I’ll show you what that data looks like when we break it down based on whether the batters were at home or on the road:

The Astros’ pace gap was significantly larger at home than it was on the road, which is what we would expect to see if their opponents were worried about a special scheme in operation at Minute Maid Park. Also of note is that no other team in 2018 had a home pace gap as large as the Astros did: Opposing pitchers slowed down more in Minute Maid than they did at any other park.

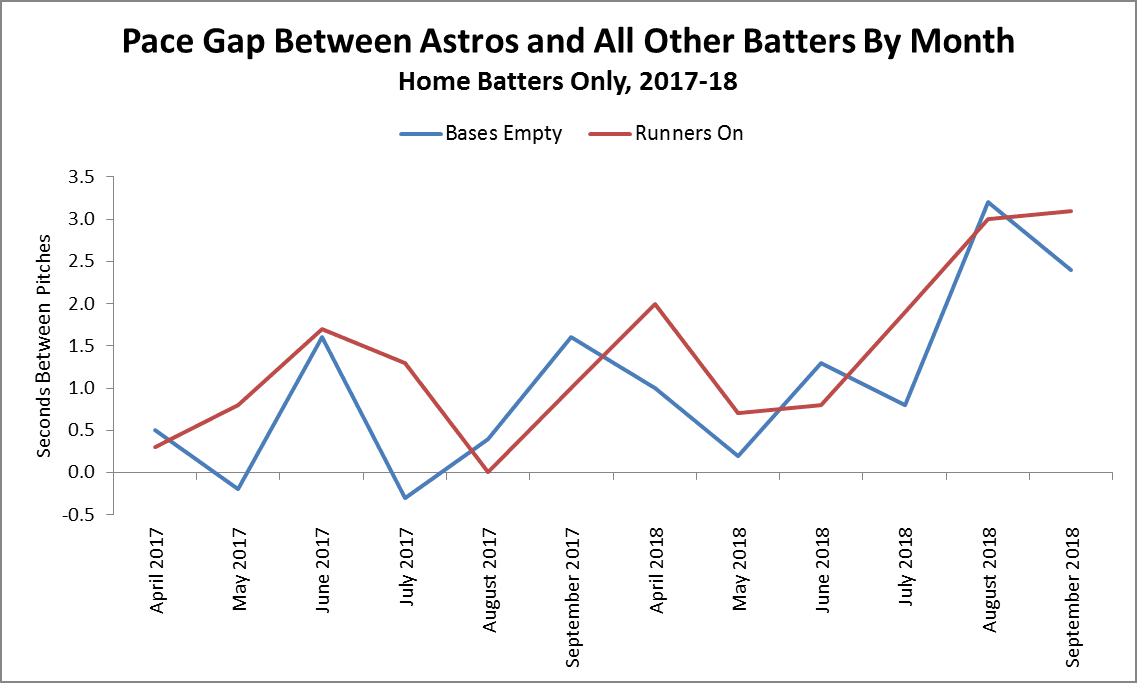

If we examine that trend by month, we find that the Astros’ pace gap soared in the last two months of the 2018 regular season.

Those last two months encompass the period when Jackson and Heaney made their extra-slow starts at Minute Maid. The A’s and the Angels were two of the four teams whose pitchers slowed the most at Minute Maid in 2018 relative to their typical pace; the other two were the Diamondbacks and the Twins, who played their only 2018 games in Houston in September. (The Astros’ other AL West rivals, the Mariners and the Rangers, don’t appear to have switched up their signs as assiduously as the A’s and the Angels, based on pace.) The commissioner’s report concluded that “the Astros stopped using the replay review room to decode signs because the players no longer believed it was effective.” If that’s true, their minds may have changed because so many teams had started defending against the Astros’ sign stealing by late 2018.

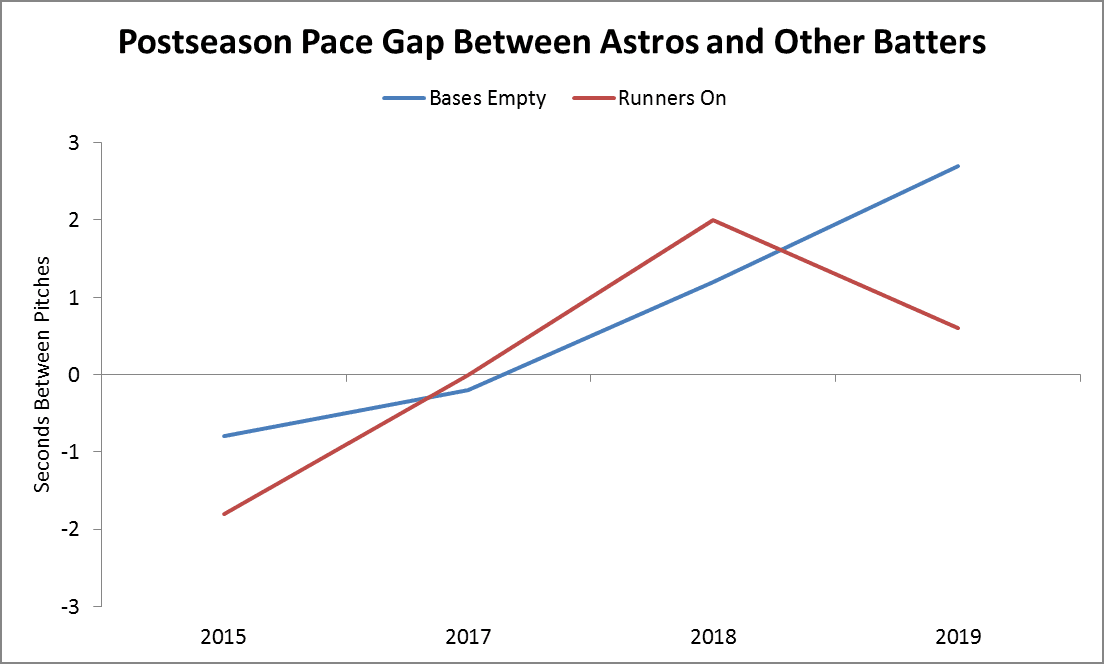

There’s one more way we can check for increasing leaguewide awareness of the Astros’ unsavory activities: by studying postseason pace. The graph below shows the postseason pace gap between the Astros and other playoff qualifiers in each of the past four postseasons in which the Astros have appeared.

The Astros played only six postseason games in 2015, and eight in 2018, so some of these samples are small, but the trend is pretty apparent. In the 2015 and 2017 postseasons, pitchers didn’t take more time between pitches against Astros batters than they did against other clubs’ batters. That may seem surprising, considering that some sign-stealing rumors had already started to swirl by 2017, when MLB censured the Red Sox for relaying signs via Apple Watch. Teams devote more time and attention to advance scouting opponents when October rolls around, and the heightened postseason stakes justify the inconvenience of going to greater lengths to disguise signs.

But perhaps players were complacent and resisted altering their routines until it was too late. Last week, the Dodgers’ erstwhile ace Clayton Kershaw told Tom Verducci that he didn’t switch up his signs against Houston in the 2017 World Series. “If you don’t change your signs up every few pitches with a guy on second base, it’s on you,” Kershaw said. “I just don’t want to have multiple signs with a guy on first base, you know? That slows the game down. Slows the rhythm down. And I didn’t do that in Houston. I used one sign. And I should have known.”

By October 2018, when an Astros employee was caught pointing a cellphone at Cleveland’s dugout during the ALDS, teams did know, and they acted accordingly. Postseason pitchers worked two to three seconds slower in some situations against the Astros than they did against other teams in the 2018 and 2019 postseasons, although by 2019 teams had deployed anti-sign-stealing measures against other playoff opponents.

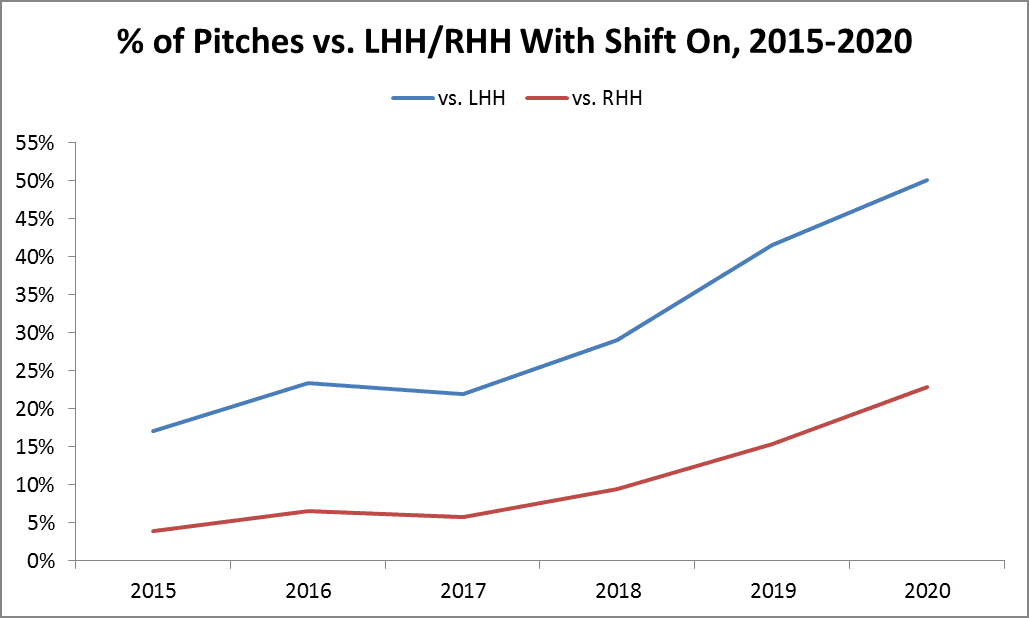

Whether or not sign stealing significantly helps hitters, it does seem to add extra time to games, which is reason enough to restrict access to in-game video (as MLB plans to do in 2020) or use technology to send signals in a more secure way. Admittedly, it’s not a ton of extra time; the average game features roughly 300 pitches combined across both teams, so even if we were to assume that sign stealing tacked on 1.5 seconds, on average, between pitches to Astros batters in 2018, the increase in the length of Astros games would have been only about four minutes. However, most of those extra seconds add no entertainment value to the game, and if unfettered access to real-time video had persisted, teams might have had to take Lucroy-like measures against every team, which would have deepened the impact on pace and time of game. The average regular-season game time reached a record 3:10 in 2019, and while the latest climb had more to do with increases in scoring, pitching changes, and pitches per plate appearance than pitcher pace, precautions against postseason sign stealing helped inflate the time between pitches with runners on base in each of the past two Octobers to an unpleasant 28 seconds.

“I think we were slow to appreciate the risk on this topic,” Manfred acknowledged last week, adding, “I hate where we are right now.” But, the commissioner continued, “By 2018, we were on the corrective action. When I say we were slow, we were slow by a few months. Look, I don’t think that that’s the worst reaction time of all time. Do I wish we would have got there a little sooner? Yeah, I do.” There’s some truth to Manfred’s defense; the league began monitoring replay rooms with on-site personnel in the 2018 postseason, and the pace stats suggest that most teams started trying to counter the Astros in earnest not too long before that.

However, MLB failed to foresee the nefarious effects its replay rooms would have or come down hard on offenders until Fiers forced its hand. As Paul Dickson, author of The Hidden Language of Baseball, told me on Effectively Wild this week, “It was like MLB brought the snake into the Garden of Eden and then wondered why Adam bit the apple.” The league’s laissez-faire approach put pressure on the players to protect themselves. Not every combination of catcher and pitcher was as vigilant as Lucroy and Jackson. But it seems like a lot of them were more vigilant than the league.

An earlier version of this piece misstated how many games the A’s needed to win to take first place from the Astros. It also misstated when Mike Fiers joined the A’s; it was in August 2018, not during spring training that year.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.