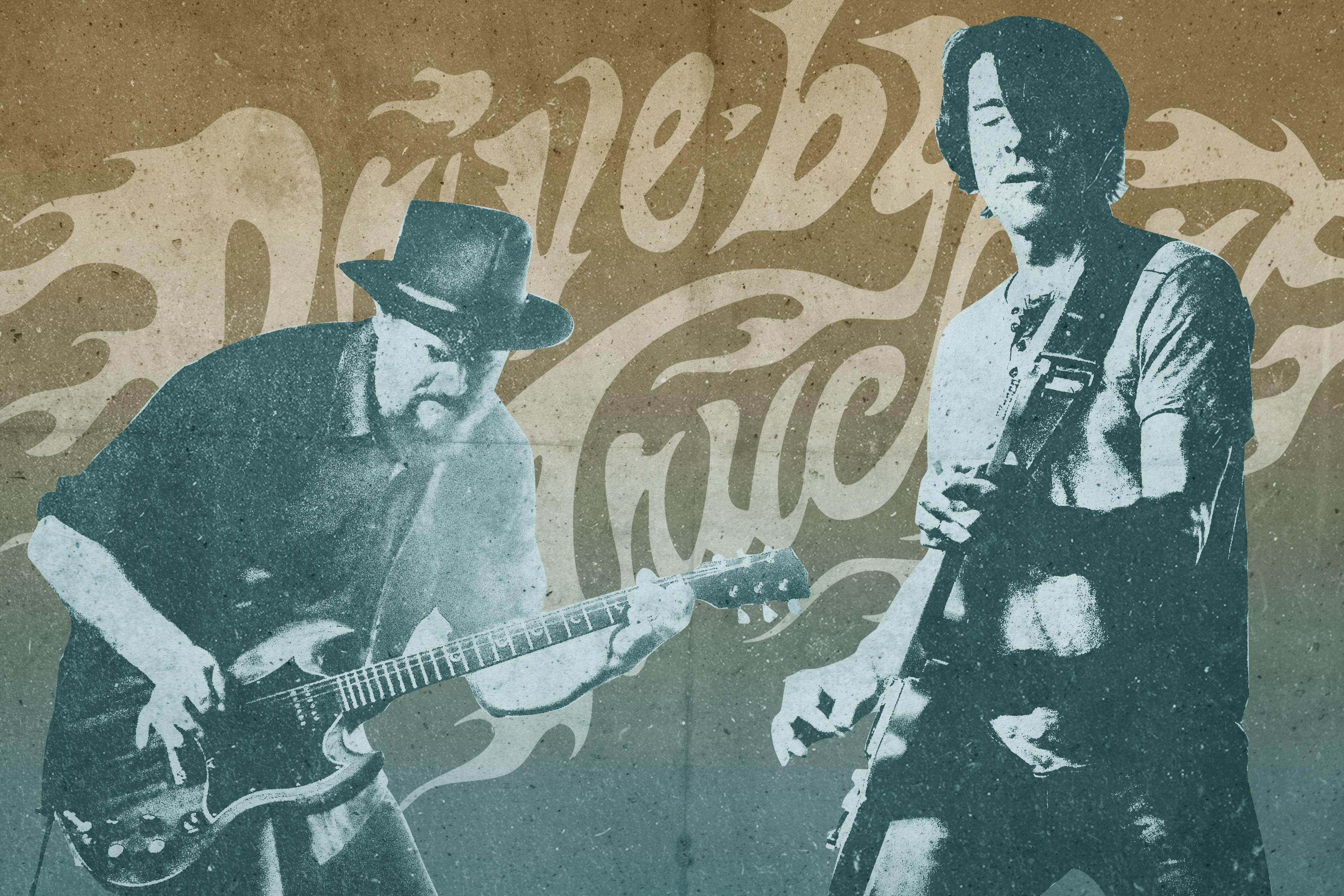

Across the Great Decline: The American Carnage of the Drive-By Truckers

The long-running group return to take stock of a nation on the brink, its institutions in peril, and its citizenry increasingly polarized, and wonder: What’s a Southern rock band to do in the twilight of the American experiment?

There’s a lyric from “Armageddon’s Back in Town,” the exhilarating first single from the 12th and most troubled studio LP by the great American institution the Drive-By Truckers, that goes: “There’s something to be said for hanging in there / That’s the point of hanging around too long.” Few would say that the Truckers (or DBT, as they are sometimes known to their devoted fan base) have worn out their welcome, but a sense exists among the beautifully damaged grooves of their great new record that they have begun to sincerely wonder whether, after a 25-year stretch that has seen them make as much important music as any American band of their era, enough is enough. Or, more darkly, if enough was anything at all.

Drive-By Truckers have always skewed dark and funny, but The Unraveling presents an altogether higher order of gallows-humor despair with respect to the ongoing diminishment of our political and social institutions. Much as the Mekons are shadow historians of the British Empire’s long and precipitous postwar decline, DBT have dedicated their careers to marking the minutes of the postindustrial American experiment, from the inspiring to the abominable. Often their critiques have been unsparingly critical—like all dyed-in-the wool patriots, the disappointment in the nation’s failure to live up to its higher ideals cuts deep and resonant. In an email to The Ringer, DBT co-frontman Patterson Hood says, “I consider this to be one of the most personal records we’ve ever made, even if the songs deal with ‘political’ subject matters. As I keep saying, political is personal.”

Past Truckers albums have burned with incandescent anger at specific targets: the NRA, corrupt police, George Wallace. “Thoughts and Prayers,” from the new record, a firebrand song worthy of Phil Ochs, is a reaction to the egregiously tepid response of legislators and gun manufacturers to any given school shooting. But in the main, The Unraveling proceeds along a murkier track, offering a broader and more harrowing origin story for our current state of strangulating corruption: All politics are local and all municipalities are fallible. “There’ll be no healing / From the art of double-dealing,” Hood sings on “Armageddon’s Back in Town.” In 2020, in America, if you say that you are lying, you might be lying. Late-night talk show comedians tie themselves in knots trying to make light of events manifestly without mirth. Counterfeit governance, counterfeit media, counterfeit opposition. In Hood’s wry and bewildered assessment: “Can’t tell the rabbit from the hat.”

“There’s No Shortage When It Comes to Hearing Voices”

An abbreviated version of the novelistic DBT saga goes like this: The band convened in Athens, Georgia, in the middle of the 1990s, sparked by a reconnection between ace singer-songwriters Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley—childhood friends from the Muscle Shoals region of Alabama who had previously experienced some success playing together in the dB’s-like power pop outfit Adam’s House Cat. In the years after their first band’s split, Cooley’s and Hood’s sensibilities grew darker and more ambitious, and the reconfigured duo shared a desire to parse the complicated roots of their Southern heritage and its endless and bothersome contradictions.

They accumulated a loyal following over the course of two LPs and countless raucous club shows before 2001’s almost comically ambitious double album Southern Rock Opera blew the mind of critics and audiences alike, with its panoramic world-building, odes to past contretemps between Ronnie Van Zant and Neil Young, and barely sublimated nightmares about their own destiny. Southern Rock Opera’s ostensible framing device follows the triumph and tragedy of Lynyrd Skynyrd, who walked these very paths and ended up mostly dead in a small-plane crash trying to get from one gig to the next efficiently.

Besides Hood and Cooley, members tended to rotate in and out of DBT. In 2001, the group recruited fellow Alabama-born wunderkind singer-songwriter Jason Isbell, much like the Merchant Marine might have done. Isbell was roughly 10 years younger than the rest of the band, and his time in DBT would prove both a rough education and a signal moment when three legitimately great songwriters were occupying the same outlet for one of the first times since the Beatles. The records that triumvirate made—Decoration Day, The Dirty South, and A Blessing and A Curse—are all classics that redefined the landscape of Southern rock by subversively rearranging the porch furniture in a million unexpected ways.

For a time, DBT skated close to the edge. Complications and conflicts with addiction played a role in Isbell’s departure from the group in 2007, followed by his decision to get clean, strike gold, and begin his subsequent run as a bona fide and decorated Nashville hitmaker. Before moving on, Isbell contributed a number of powerful entries into the group’s stacked canon, including “Outfit” and “Goddamn Lonely Love.” Isbell and the Truckers remain cordial mutual admirers, but the question always lingers: What if Mick Taylor had stayed in the Stones after It’s Only Rock ’N’ Roll? What if Joe Strummer had never fired Mick Jones? What if Isbell and the Truckers had managed a longer run? DBT has always done both the music and the mythos to the hilt.

“Folks Working Hard for Shrinking Pay”

Post-Isbell, Cooley and Hood defused questions about the meaning of his departure by releasing one great album after the next. 2010’s The Big To-Do is an Allmans-by-way-of–Hüsker Dü tour de force, while 2014’s English Oceans is all Exile and ecstasy, a painful and cathartic reckoning with friends who have been lost in the pursuit of whatever it is they’ve been pursuing for so long. Through it all—the beginning, the Isbell years, the aftermath—what came through was the pride in the work, and the sense that they would never take a chance on seeing their audience disappointed. An honest dollar for an honest day.

DBT is dedication to work personified. They belong to a pre-boomer mentality that believes in the sometimes complicated virtues but ultimately democratic prospects of collectivism, pluralism, and something like a level playing field. The unraveling referred to in the album’s title is the systematic decades-long dismantling of those ideals, orchestrated by a feckless and cruel political and corporate class whose belligerence is based on nothing short of their own blinkered self-regard. Forty years of financial deregulation, unfunded foreign wars, and tax cuts for the rich, all culminating in Donald Trump’s xenophobic shamelessness. Don Henley’s 1984 classic “The Boys of Summer” predicted the fractious psychology and rise of an angry investor class coming out of the largely failed social experiments of the 1960s: disillusioned, acquisitive, and out to find and harm the first person who slightly disorders their wounded psyche. This is how you get Bill Clinton’s senselessly punitive “welfare reform.” This is how you get a Senate preoccupied with stripping away fractionally costly health care options for the working poor on the laughable pretext of budgetary concerns. This is rocking in the free world. This is hell.

“Is There an Evil In This World? Yes, There’s an Evil In This World”

Cultivate your own garden. So goes the received wisdom of Candide at the end of Voltaire’s novel by the same name, meaning, basically, deal with what you can affect. In a nervous time, The Unraveling relies most on the comic and creepy small-town picaresques that have always been the band’s unfailing strength. With everything else seeming irretrievably broken, the Truckers concentrate on the individual lives that might still be salvaged.

The lithe groove of “Heroin Again” is a cautionary tale from the perspective of hard-won experience that contains the DNA of both Prince’s “Sign o’ the Times” and Neil Young’s “Needle and the Damage Done.” So many friends lost, so much pointless suffering, a prayer not to overdo it. Hood reflects on the days when the band’s own wildness threatened to subsume them. He feels lucky. “I’ve always been blessed that I could move on from my more reckless endeavors before things got out of hand. Nowadays, I’m pretty boring as far as the rock and roll lifestyle goes.”

But there’s those you lose along the way. And the survivor’s guilt.

“We somehow always drew the line at heroin, even in our hardest driving and partying days,” Hood recalls. “Thankful for that. We had a very dear friend who worked for us, that we literally saw grow up. Wonderful young man, super talented and smart as shit. About to graduate from college with straight A’s. OD’d a month before. Broke all our hearts. None of us had any idea whatsoever that he was doing anything like that. I wrote the first draft of that song shortly after his memorial.”

“21st Century USA” is ominously offhand direct reportage from a middle-sized city caught in the endless cycle of wage reduction and longer hours and layoffs, and is particularly disturbing because it offers nothing, really, in the way of redemption: “With Big Brother watching me / Why should I feel so alone?” The old fault lines between labor and management have been replaced by something baffling and banal and deeply sinister: a hydra-headed, impenetrably complicated multinational cabal of interconnected ownership groups whose superpower is their anonymity. It’s hard to know which side you’re on when you can’t even see the playing field.

Elsewhere, Cooley’s “Grievance Merchants” is a Marty Robbins–by-way-of–Gun Club indictment of the cloistered worldview that permeates the most miserable outposts of the 8chan right. “Give a boy a target for his grievance / And he might get it in his head they need to pay.”

The Unraveling concludes with an offering. The near-nine-minute confessional “Awaiting Resurrection” is a wobbly procession shot through with a bone-chilling fear of death and a deeply grasping hope for life. It’s a slow-burning meditation on how far we’ve fallen and how we might conceivably get back that wouldn’t sound out of place on Sly & the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On, a similarly despairing American classic that seeks a way through institutional corruption with panicked grasps at personal virtue.

“I find inspiration from trying to talk about this shit with my kids,” Hood reflects on the question of moving forward. “How to answer their questions. How to explain my second grader’s lock down drill to him or answer his questions about little Mexican kids being ripped from their mother’s arms and put into holding pens. What the fuck?”

The Unraveling is riddled with real-life victims of our current moment. There is no clear path forward, but there is this left to fight for: Without resistance, whatever comes next may well be even worse. As Leonard Cohen once opined, in response to objections about America and its manifold flaws: “You’re not going to like what comes after America.”

The final lyric on The Unraveling goes, “In the end we’re just standing / Watching greatness fade.”

Elizabeth Nelson is a Washington, D.C.–based journalist, television writer, and singer-songwriter in the garage-punk band the Paranoid Style.