Wearing a black-and-gold “KB” pin over his heart and Kobe sneakers on his feet, Frank Vogel stepped into the Staples Center auxiliary press room on Friday night ahead of the Lakers’ game against the Trail Blazers. Since Sunday, when a helicopter crash took the lives of nine people including Kobe Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, Vogel had become the front-facing member of the franchise, speaking for everyone who mourned in the shadows. Friday’s game, the Lakers’ first since the tragedy, meant yet another time he had to try to bring perspective to an emotional week.

“It feels like we’re mourning every minute of every day this week,” Vogel said. “Basketball is our refuge.”

Over the preceding six days, shock turned into grief, which by Friday had turned to somber remembrance. And throughout this emotional evolution, Staples Center has become a mecca where fans from all over Southern California have flocked to honor Kobe and the rest of the victims by placing their own mark on an ever-growing memorial.

What had started Sunday with fans crowding around a few clusters of flowers and candles only expanded on Monday, with bands playing music at the plaza, more fans showing up, and even people shooting paper balls at a trash can while shouting “Kobe!” That scene continued on Tuesday while the cast and crew of TNT’s Inside the NBA held a special broadcast to share their connections to Kobe and their emotions with viewers. The game that was scheduled to take place that night between the Lakers and Clippers had been canceled, so Jerry West, Shaquille O’Neal, Charles Barkley, Dwyane Wade, and Reggie Miller, among others, attempted to provide some kind of catharsis through their memories.

Somehow, though, life at Staples had to go on. It did so Wednesday with a Kings hockey game, on Thursday with a Clippers game, and on Friday, as the Lakers returned to honor Bryant and his family. That tribute capped off a week that was full of emotion not just for Lakers fans but for those who worked inside the arena, those who played with or against Kobe, and the countless people all over the world who still can’t believe he’s gone.

The break room inside Staples Center was bustling. It was the day of the Grammys, and the ushers, security guards, and staffers were getting ready to put on yet another event in the arena. Dan Olson had just slipped on his bright red blazer, the distinct look reserved for the stadium’s security ushers, when he heard the whispers. The name “Kobe” kept coming up, so Olson, who’s worked at Staples since 2007, looked at his phone and saw the tragic news.

“I thought, maybe it’s a hoax. Then I saw the TV and the news became real,” Olson said, while standing just outside the hockey rink Wednesday night. The L.A. Kings were getting ready to face off against the Tampa Bay Lightning in what would be the first sporting event in the facility since Sunday.

Kings and Lightning players both warmed up wearing commemorative purple T-shirts with a yellow heart that featured the nos. 8 and 24 and the names “Kobe” and “Gigi.” The Kings held a pregame ceremony that featured the booming voice of retired Hall of Fame broadcaster Bob Miller recapping the tragic story, expressing condolences, and recounting Kobe’s accomplishments. When Miller reached the point in Kobe’s résumé that said “two Olympic medals,” a fan from the stands—which were dotted with yellow Lakers jerseys—yelled out, “That’s damn fucking right!” Then, after a 24-second moment of silence, another fan began a “Kobe” chant that went on to echo throughout the arena.

Deep within Staples Center, where staffers check in for the night, there is a whiteboard with rules, assignments, and messages. On Wednesday night, the first message, written in purple marker, simply read, “RIP Kobe & GG.”

Wednesday was a hectic yet somber night for the arena staff as they got back to work. Ushers read papers and shuffled to their posts. One veteran usher explained to a younger one what was different about working hockey games versus basketball games. The elevator attendants switched shifts in the middle of the second period, and when the arriving attendant—a man named Freddy, who’s worked at Staples since 2014—was asked how he felt, he just said, “Sad.”

Freddy had never interacted with Kobe, but was always drawn to him. Before Freddy ever worked at Staples, he would go to games just to watch Kobe play. And even once he did start working at the arena, he would come in on off-days to see his favorite player. “He was amazing,” Freddy said. “Seeing him in the hallways wasn’t as special as seeing him play.”

As the gray-haired Olson will tell you, when you work at Staples for a long time, the teams, the players, and the other workers become your family members, too. Another usher, who did not want to share his name for this story but has worked at the arena for 15 years, agreed, saying, “If you go through the years and watch all of [Kobe’s] highlights, we’re right there. You’ll see us.”

For the countless fans celebrating Kobe’s life outside the arena, his legend is continuing to grow. But for those inside, those people who caught a smile, a scowl, maybe even bumped his fist, his legend was largely crystallized in those personal moments. For a handful of hours 41 days a season, over the course of 20 years, Kobe and those arena workers were peers, all trying to do a job as best as they could. It’s why on Sunday, when the mood turned somber and at least one worker began tearing up, Olson had little choice but to do what he had seen Kobe do every game day for more than a decade: go to work.

Standing inside the Staples Center visitors’ locker room on Thursday night, Kent Bazemore easily recalled his favorite Kobe memory. Back in February 2014, Bazemore had been traded from the Warriors to the Lakers in a deal for Steve Blake, and just two days later he helped the Lakers beat the Celtics by nine points in Los Angeles. He was feeling upbeat, and he wasn’t alone. The entire Lakers locker room was elated about getting the win over a rival team.

Then Kobe walked out of the showers, his face frozen, his glare searing, and his words—to this day—unforgettable: “Y’all motherfuckers still ain’t good!”

This was Bazemore’s childhood hero, his generation’s Michael Jordan, the player he had defended in arguments with friends. The tone had been set. And it was quickly reinforced when Bazemore learned that Kobe beat every player on the team to practice each morning. “You could see and feel the fire he played with,” Bazemore said after his Sacramento Kings faced the Clippers on Thursday night.

The actual basketball game that happened that night felt secondary to the conversations that took place in nearly every interview. Luke Walton’s entire pregame press conference revolved around his former Lakers teammate, whom he played with for nine seasons and won two titles with. Walton talked about how his Kings team got into L.A. late Tuesday night and walked to the Staples Center memorial, where people were still chanting Kobe’s name at 2 a.m.

“That street is where we boarded our buses when we won a championship, drove through the city, and had the drive of our lives,” Walton said. “You think you’re doing better and then you pull into Staples Center, and how many times have we walked through and Kobe is out there getting his shots, or you saw Vanessa and the girls outside the locker room? I totally forgot about that until I walked by right now. It’s still really hard.”

Walton also reminisced about his personal relationship with Kobe, which he boiled down to this: “I passed the ball to him,” he said. “Phil [Jackson] would yell at me to make the right pass, and I would look at Kobe and he’d tell me the right pass was to him.”

Kobe’s legendary work ethic and drive is what Rico Hines, player trainer and assistant for the Kings, remembers most, especially during the summer following Kobe’s Achilles injury. Kobe was in New York at the time and asked Hines to work him out for a day at St. John’s. “He was like, ‘Rico, you know I wanna go at 5:30 a.m., right?’” Hines says. “I was like, ‘I’ll be there.’” Kobe showed up at 5:30 with his longtime physical trainer, Tim Grover, and got to work, spending the first 45 minutes simply doing footwork drills. Hines was amazed.

On Thursday, Hines was feeling very different emotions. As recently as this summer, Kobe had been in touch with him about coming to the star-studded UCLA summer runs that Hines puts on, which Kobe had attended when he was younger. It was clear to Hines that Kobe wanted to teach and impart his knowledge. “That never wavered,” Hines said. “He always believed in working on your game through the summer against the best competition in the world.”

Bazemore had his own learning experience with Kobe. Bazemore’s eyes light up when he remembers how he once DM’d Kobe on Twitter to discuss a book Kobe had recommended, Zen in the Art of Archery, and Kobe responded. “I was so excited that he messaged me back,” Bazemore said.

The Clippers did their part to remember Kobe on Thursday. Bryant’s two retired jerseys were left uncovered in the rafters, and they played a tribute video pregame. That video was narrated by Paul George, who jumped at the opportunity to lend his voice—he grew up a Bryant fan in Palmdale, California. “It’s always going to be tough, especially being here in L.A.,” George said postgame. “Every time we’re in this arena, we’re being reminded of him just being in the rafters.”

Kawhi Leonard went through warmups with the team on Thursday—wearing a shirt that sported the no. 24—but lower-back tightness kept him out of the game. He stayed for the contest, though, and as the game ended, he shuffled along a hallway of the arena accompanied by his 3-year-old daughter, Kaliyah. They held hands—or, rather, because of their size difference, her entire hand wrapped around his index finger. When they neared the exit, she made a noise that sounded like her toddler version of “Dad.” Kawhi looked down at her and smiled.

“It’s your job to try to perfect it and make it as beautiful a canvas as you can make it.”

Kobe’s voice boomed throughout Staples Center. A montage of highlights and interviews from his 20-year career—soundtracked by a cello at center court playing “Hallelujah”—was displayed on the Jumbotron during the Lakers’ emotional pregame ceremony Friday night.

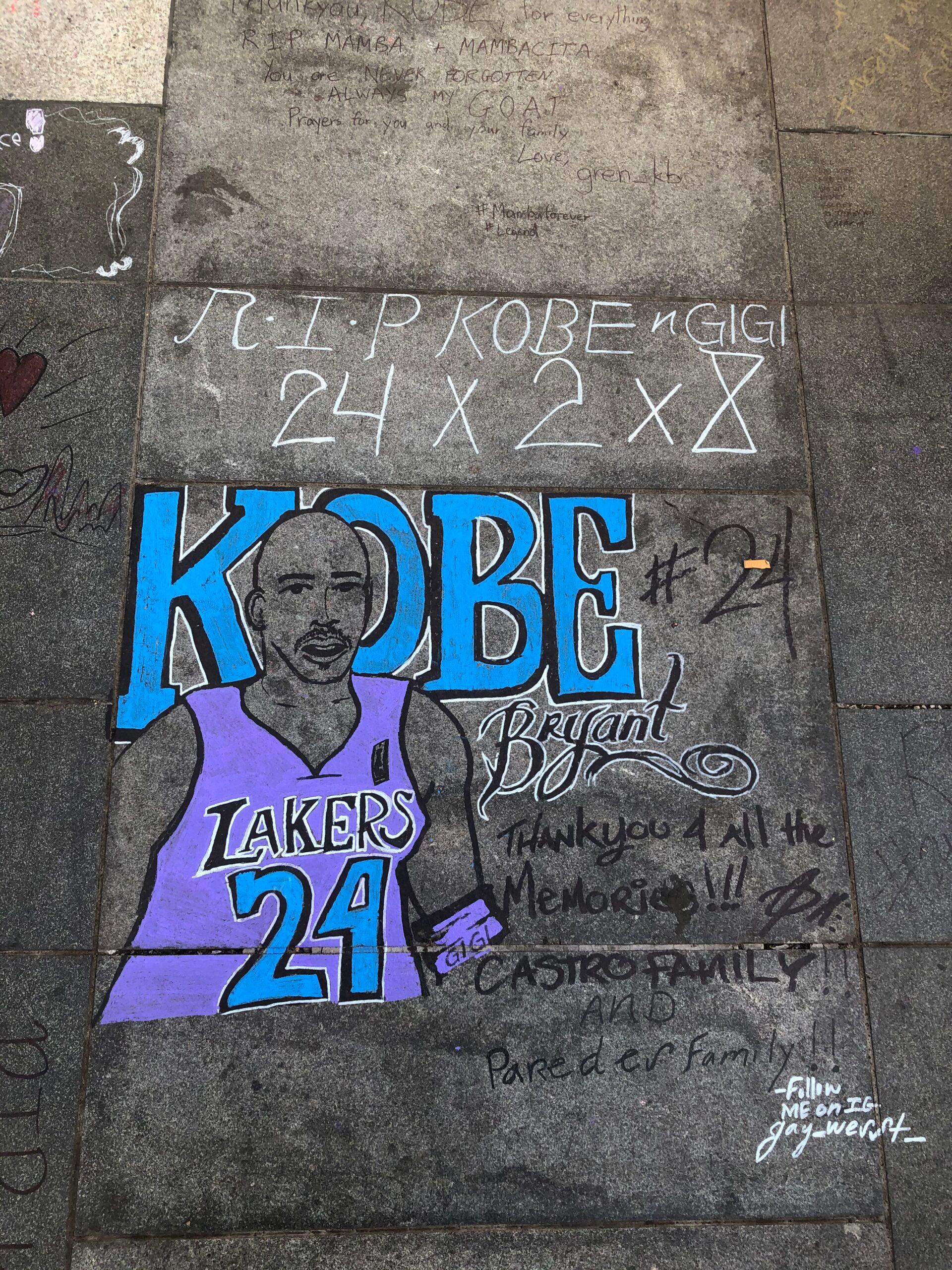

The evening had been plenty heavy already. Outside, L.A. Live was as packed as it had been all week, even though the Lakers had told fans that the game wouldn’t be shown on the outdoor screens. They weren’t there to watch basketball, anyway. Sixteen large white canvases stood along Chick Hearn Court, and they were filled with messages for both Kobe and Gigi. The plaza was packed on both sides with flowers, candles, letters, paintings, frames, jerseys, shoes, and notes, and the concrete floor itself had been turned into a canvas where fans had written out messages and painted Kobe’s face. This place no longer belonged to AEG, the company that owns Staples Center. It had become the fans’.

Inside, things only seemed more surreal. Two-sided T-shirts were draped over each seat—no. 8 Bryant on the front, no. 24 Bryant on the back—except for the two seats courtside that had been left empty for Kobe and Gigi. Those seats, where the two had sat in late December to watch the Lakers play the Mavericks, were occupied by their respective jerseys and bouquets of roses.

Two hours before tipoff, as the names of the nine crash victims were displayed on both the Jumbotron and the digital banner around the arena, a group of girls and their families wearing Mamba Academy gear walked through the Staples Center tunnels. They were members of the team that Gigi, Alyssa Altobelli, and Payton Chester had been traveling to play with on Sunday. Silence followed the red-eyed group as they entered into a VIP room. They would later be seated in the front row for the pregame ceremony.

An hour before tipoff, Trevor Ariza exited the Blazers locker room with his head down and custom gold, white, and black Kobes on his feet. The former Laker jogged out toward the court, hugged a staffer, said hello to James Worthy, then looked up, drew a deep sigh, and began warming up. After some time, Ariza returned to the locker room, where the Lakers’ last game—the one they played Saturday night against the Sixers—was being shown on a screen. As Ariza sat down at his stall, the ESPN broadcast put up a graphic that made everything feel all the more unbelievable: “LeBron James is 14 points away from passing Kobe Bryant on the all-time scoring list.”

Just before tipoff, LeBron stood at center court and spoke for the first time since Sunday. He came out with a written message but instead opted to “go from the heart.” He talked about how he had seen the familial side of Laker Nation this past week, and how he wanted the game to be a celebration of Kobe. He concluded with his own spin on a familiar quote. “In the words of Kobe, ‘Mamba out,’” he said. “But in the words of us, ‘not forgotten.’”

Inside the Lakers locker room after the 127-119 loss to the Blazers, Jared Dudley reminisced about the difficult shots he had seen Kobe hit in the 2010 Western Conference finals when he was with the Suns. Quinn Cook remembered how Kobe always wrapped him up in a big hug, asked how his mom was doing, and gave him advice. “I wish they were still here,” he said while wearing a custom T-shirt with Kobe and Gianna on the front. He teared up. “I don’t know where we go from here.”

Alex Caruso, meanwhile, couldn’t forget one part of the pregame ceremony. “The videos of Kobe with the guy playing the [cello],” Caruso said. “That was the peak for me.”

For many around Staples on Friday night, that video had struck the perfect tone. For those few minutes, no one else needed to put his legacy into words or explain the hurt that the crowd was feeling. Kobe was simply allowed to do what he had done his whole career—what had endeared him to all the fans inside the arena and the countless more outside: He told his own story.