The premiere episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, “The Pants Tent,” aired in October 2000, when Bill Clinton was president and Al Qaeda was most infamous for blowing up the USS Cole. The world looked different than it does today, but Curb, which sprang forth from the mind of Larry David almost fully formed, was essentially the same. In one evening on that episode, TV Larry runs afoul of his manager, Jeff (who put him on speakerphone in the car without warning), his friend Richard Lewis’s girlfriend (who doesn’t leave room for Larry in a movie theater aisle and then accuses Larry of looking at her breasts), and his wife Cheryl’s friend Nancy (who mistakes the bunched-up fabric in the crotch of his pants for an erection). As Larry says to Cheryl, recapping the conflicts, “Strange night, huh?” Well, no, not really—that was a pretty normal night on Curb. Almost 20 years later, it still is.

Curb comes back on Sunday for the start of Season 10. Although the Season 9 finale ended with Larry fleeing from an attacker who hadn’t heard that the fatwa on his head had been called off, no one is wondering whether that cliffhanger will be resolved. There are no mysteries to be solved, no major plot twists to be anticipated, no high-stakes landings to be stuck. The series originated a year after The Sopranos and Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, when The West Wing was in its first season and Must See TV still featured Friends, Frasier, and Will & Grace (in its original run). It debuted before the advent of streaming services, before cord-cutting caught on, before social media made TV moments into memes. The industry gets disrupted repeatedly; the audience evolves. Curb abides.

We can’t call Curb a constant, because it’s been on break as often as it’s been active, taking at least one calendar year off between each season since Season 5, including a six-year hiatus after Season 8. Whenever it wanders back into our lives, though, it looks a lot like it did the last time it left. Curb’s thematic and stylistic consistency is one of the series’ selling points. As an HBO promo for Season 9 promised, “He’s back. And nothing has changed.” The Season 10 teaser advertises an “all-new season,” but the content of the teaser, in which Larry loses patience with a slow toaster, is similar to Larry losing patience with a soap dispenser or a piece of plastic packaging last season—or, for that matter, Larry struggling with a slow toaster in Season 6. Both seasons’ trailers climax with montages of incensed people swearing at Larry or demanding that Larry leave, a trope that dates back to the beginning of Curb.

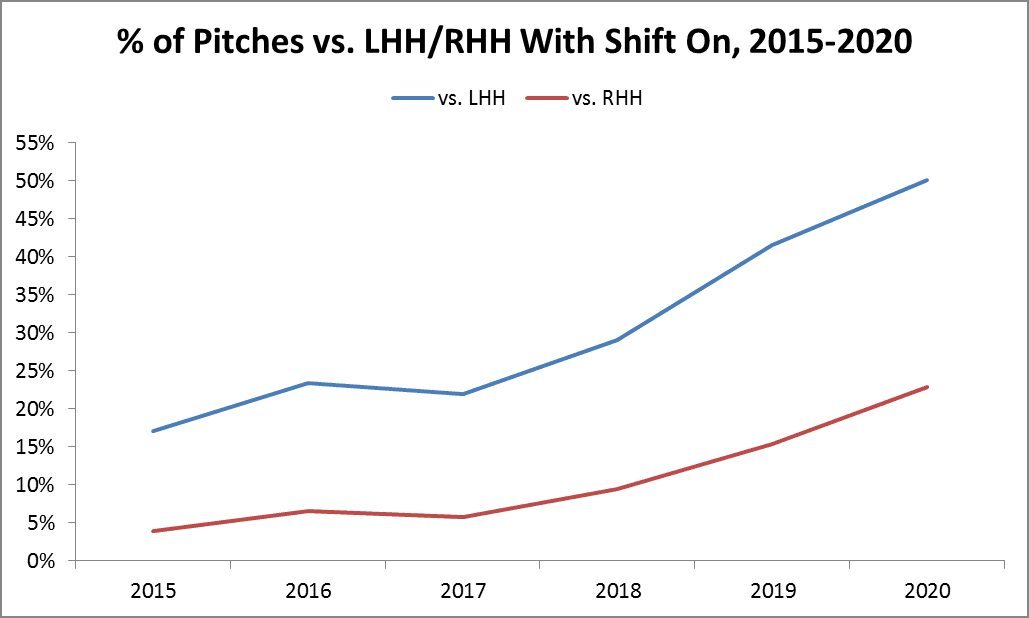

Because Curb continues to be the same sitcom as ever, anyone who’s disliked Larry before probably won’t be boarding the Curb bandwagon in Season 10. Conversely, anyone who has liked Larry almost certainly still will. As the chart below shows, the perceived quality of Curb, based on IMDb user ratings, has been extremely stable. The average ratings for every season since the slightly lower-rated first one have hovered between 8.4 and 8.6.

Maybe that flat trend line comes from the fact that the network doesn’t dictate the pace of production on Curb; David makes new seasons whenever he has new ideas, not when the broadcast schedule says so, so it makes sense that the quality of the output wouldn’t fluctuate wildly. And because Curb comes and goes, it doesn’t wear out its welcome: Its 10-episode seasons last less than three months, and by the time the show returns, the preceding season is distant enough that the old seems somewhat new again. More than that, though, this immutability stems from the fact that for better or worse, David largely hasn’t tried to adapt to shifting tastes, borrow from flavors of the month, overhaul his craft, or comment on current cultural events. His humor, and his series, stay in their well-liked, lucrative lane.

I recently rewatched Season 1 and some of Season 9 and was struck by how little difference the 17 years between them made. Time hasn’t taught TV Larry how to play well with others, and he hasn’t talked others into living like he does. His surroundings have changed in one noteworthy way: Cheryl moved out, and Leon moved in. In the Season 1 episode “Affirmative Action,” David tried to poke fun at his own history of making comedies with predominantly white casts; since then, his casts have included more people of color. And as David has become more comfortable on camera, his performance has grown a bit broader.

Beyond that, Curb’s continuity is close to complete. “Frolic,” the famous theme song, was present from the start, as was the series’ simple look. The director of “The Pants Tent,” Robert B. Weide, also directed an episode in Season 9. The first “prettay good” appears in Episode 3, and the staredowns started in Season 2. David and executive producer Jeff Schaffer, a Seinfeld veteran, have been outlining episodes together since Season 5. Save for the late, great Bob Einstein, whose endearingly deadpan Marty Funkhauser joined TV Larry’s friend group in Season 4, the core social circle hasn’t sustained any serious losses: Season 1 staples Jeff Garlin, Susie Essman, Ted Danson, Richard Lewis, and Cheryl Hines will all be back this year.

Like Curb, David doesn’t look all that different than he did in 2000: He’s slightly slimmer, his face is more deeply lined, and what hair he has left has turned white, but his baldness, his signature spectacles, and his distinctive wardrobe had cohered into a look long before Curb debuted, eclipsing subsequent signs of aging and reinforcing the feeling that Curb is frozen in time. (Not everyone on the series has stayed the same: Although the old David has endured, Danson has morphed from the dressed-down, past-his-prime former heartthrob of Becker to the besuited snow-white fox of The Good Place.) David, of course, is only partly playing a character, and the idiosyncratic comedic sensibility he honed on Seinfeld was well defined two decades ago. He was well into his 50s when “The Pants Tent” premiered, so perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s stuck with what’s worked. His main creative detours during Curb’s six-year layoff, the HBO movie Clear History and the Broadway play Fish in the Dark, seemed, as I noted in 2015, like collections of Curb B-sides. “Yes, Larry lacks range,” I wrote then, but “few actors get so much mileage out of playing themselves.”

Because Larry has always dressed according to the casual compass of his own inner stylist, one can’t easily situate Curb episodes in time, as one can with Jerry’s dated fits from Seinfeld. No one talks about how modern technology would spoil classic Curb episode scenarios, as they do with David’s first show, and there’s no Curb equivalent of the @SeinfeldToday Twitter account, both because Curb is still with us and because it arrived after cell phones, the internet, and GPS had hit the mainstream and shaken up the logistics of daily life. David’s hypersensitive sense of social codes and conventions has sometimes prompted his Curb character to comment on more modern methods of interaction, as in Season 9’s best episode, “The Accidental Text on Purpose,” or the following episode’s bit about Uber, but the world isn’t waiting for him to weigh in on TikTok or Fortnite. The real LD isn’t extremely online, so we wouldn’t expect his alter ego to be.

Curb’s comedy depends on exposing the absurdity of inconsequential yet ubiquitous customs, not riffing on names in the news, so its subject matter and laugh lines are relatively timeless. According to a GQ profile published last week, Season 10—which will feature Clear History costar Jon Hamm—will creep into topical territory with a #MeToo plotline, a risky swing for a 72-year-old man to take. Despite the sweeping changes in social norms and values over the past 20 years, the series has mostly (if not entirely) steered clear of material that seems painfully insensitive or cruel in retrospect—partly because TV Larry, while often impolite, is rarely mean-spirited, and partly because his frustrations with others often reflect his own anal nature or ignorance. Instead of punching down, David ridicules himself.

Cringe comedy is, perhaps, a little less in vogue than it was in the wake of Curb’s breakout, but at this stage, the series isn’t truly uncomfortable to watch. Its awkwardness comes from TV Larry’s lack of inhibition, which is too familiar to faze us. Where some see a finicky, neurotic narcissist, others see a candid kindred spirit and forgive his foibles. Granted, a series that revolves around the rich-person problems of an insular, self-centered white Boomer who loves to go golfing—Larry the Country Club Guy—might not seem well suited to the age of Us, Parasite, and Knives Out. But TV Larry has been harping on the hypocrisy, pettiness, and stodginess of the social elite since Season 1, and the characters whose behavior he bemoans—the close talkers, double dippers, and schmohawks—can cross societal lines.

Like almost any other cultural institution that lasts this long, Curb has receded somewhat from the spotlight. The David brand is so established that it’s harder for him to surprise us: Give us the setup, and we can almost anticipate what he’s going to say. Amid so much competing TV, a breakneck news cycle, and a landscape of splintering audiences that don’t talk to each other, terms from Curb can’t continue to crack the lexicon like the “stop and chat” or a dozen predecessors from Seinfeld did. What’s more, it may seem pointless to obsess over small social niceties and transgressions when we know that a boor can be president, our leaders lie, and polarized politics are pushing people apart. These days, we all feel a little like Larry ranting about a senseless appointment policy and discovering to his dismay that no one else in the waiting room really cares.

Even so, it’s nice to know that this many years later, Larry is still unleashing his less repressed second self to fight for fairness, logic, and transparency in the fields of phone etiquette, line-waiting, and assessing sorries and thank yous. We may not need Curb to keep coming back, but as long as Larry isn’t out of ideas, we’ll be happy he chooses to stop and chat with strangers, if only on certain Sundays, and if only from afar.

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.