On Tuesday, Joe Biden apologized for his “mistaken vote” as a senator in October 2002 to authorize the Iraq invasion, led by former president George W. Bush. It’s not the first time Biden has apologized for his vote, and he isn’t the first front-runner in a Democratic presidential primary to regret their formative role in starting the Iraq War. He is, however, the starkest embodiment of his party’s ambivalence about U.S. military commitments in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria since 9/11, especially as President Trump now risks war with Iran. On Tuesday, the seventh Democratic presidential debate revealed a party that has struggled to invest full confidence into its opposition to the “forever wars” in the Middle East in the 18 years since Bush led the U.S. and its coalition partners to invade Iraq.

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders has drawn the starkest contrast with Biden in foreign policy throughout the campaign. Sanders and California Representative Ro Khanna coauthored legislation—the “No War Against Iran Act”—“to prohibit the use of funds for military force” following Trump’s order of a drone strike attack that killed Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in Baghdad on January 3. Trump, citing classified intelligence, says Soleimani was “plotting imminent and sinister attacks on American diplomats and military personnel” in the region, though he declined to reveal Soleimani’s plot, and has since suggested the evidence “doesn’t really matter” given Soleimani’s role in previous attacks on U.S. troops, and U.S. allies, in the Middle East. The House, with the support of a few Republican defectors, passed a war powers resolution to limit Trump’s authority to order additional strikes against Iranian targets without congressional authorization. (The measure is now before the Senate.) Trump and his Republican allies now hector the Democrats for “supporting” the Iranian regime against U.S. troops, U.S. interests, and U.S. values.

Democrats have spent the 19 years since 9/11 regretting the party’s share in the ongoing U.S. military engagements in Iraq, Afghanistan, and now Syria, and the party’s current presidential candidates have dramatized these insecurities about “muscular” foreign policy on the campaign trail. In the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries, Barack Obama emphasized his opposition to the Iraq War in order to differentiate himself from his senior rivals, Hillary Clinton and John Edwards, who had both voted to authorize the invasion as senators (Obama was an Illinois state senator at the time of vote and didn’t join the U.S. Senate until 2005). Obama used Clinton’s vote to undermine her progressive bona fides at a time when the party’s more liberal voters, especially antiwar activists, were demoralized under Bush.

But Obama hardly monopolized his party’s antiwar faction in 2008. Dennis Kucinich, a U.S. representative from Ohio who opposed the Iraq War from the beginning, embodied a far more marginal faction in Democratic politics: the left-wing pacifists who opposed the war in Afghanistan—the far less divisive invasion in terms of public opinion—as passionately as they opposed the war in Iraq. Though Kucinich, too, voted for the resolution to authorize military force that led to the invasion of Afghanistan, he went on to stump for U.S. withdrawal from the region more vigorously than the more realistic presidential contenders, including Obama, throughout the 2000s. Obama offered respectable, center-left opposition to the “forever wars” in the Middle East; Kucinich and his Republican counterpart in 2000s presidential politics, Ron Paul, offered far more vigorous opposition to military engagements in Iraq as well as Afghanistan.

Sanders, who now rivals Biden in the most recent polls, said he “was wrong” to vote to authorize the Afghanistan invasion. He praises California Representative Barbara Lee, a Democrat, the only House member to vote against the September 2001 resolution to authorize military force. Lee’s only friend in a Democratic presidential primary in the 2000s would have been Kucinich. Former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg, who served as a Navy intelligence officer in Afghanistan, also praises Lee for her ongoing efforts to “repeal and replace” (in Buttigieg’s words) the 19-year-old authorization to deploy U.S. troops indefinitely against Al Qaeda terrorists in Afghanistan and beyond.

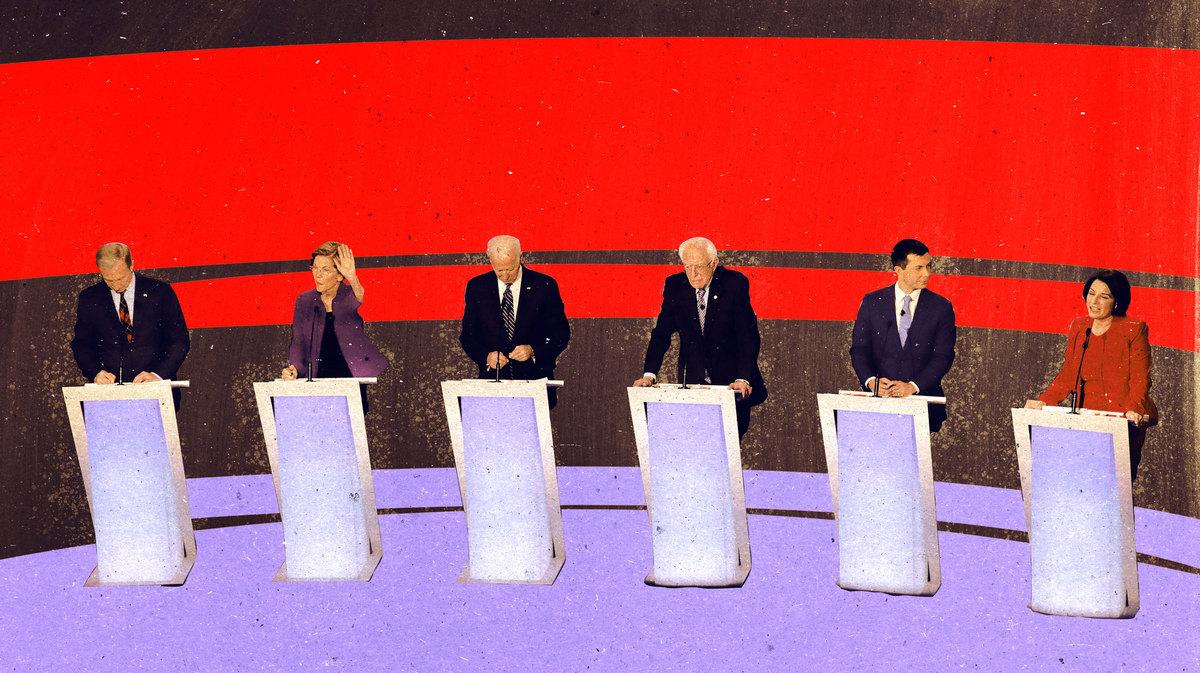

The six candidates on the stage in Des Moines on Tuesday pitched themselves as “antiwar” candidates, opposing Trump’s belligerence against Iran. In hindsight, Democratic voters wish Clinton and Biden had opposed Bush’s belligerence against Saddam Hussein. “I was right about Vietnam. I was right about Iraq. I will do everything in my power to prevent a war with Iran. I apologize to no one,” Sanders tweeted eight months before Soleimani’s death. At the debate, Sanders and Biden once again relitigated the Iraq War as the pitiless standard for presidential decision-making, and the candidates are scrambling to prove their resilience against Republicans bullying them into a third consecutive decade of carnage in the Middle East. Sanders speaks more defiantly than his Democratic rivals, even though, he stresses, he’s “not a pacifist.” In fairness, Barbara Lee says the same.