Early on in Underwater, its characters—a crew of researchers who’ve been submerged 7 miles below the ocean’s surface near the Mariana Trench in a massive laboratory—recall a colleague who liked to tell the same joke over and over again: the repetition was the punch line. Whether or not the film’s screenwriters meant for this anecdote to be self-reflexive is hard to say, but it neatly sums up the experience of watching a movie whose determination to be unoriginal represents a kind of integrity. It knows that we know what’s coming, and it gives it to us, on point and on schedule without any funny business.

There are no twists here, and no ulterior motives toward satire or subversion—nor any sense of wonder. Just a series of beats that have been mapped out for 40 years, since the debut of Alien. What’s funny is that when Alien premiered in 1979, it was dismissed by some critics as old hat. Pauline Kael famously carped that it was nothing more than an elaborately staged haunted house movie, a designation that reduced the structural perfection of Ridley Scott’s classic to a collection of tropes.

Instead of recognizing what Alien was really about—a survival-of-the-fittest allegory in which the human beings were all fighting for second place (and the android got the bronze)—Kael and other dissenters tried to fob it off as disposable genre fare. It’s arguable that the film’s only flaw was the need to have any member of the Nostromo’s crew survive at all. It was a concession to form nicely mitigated by the casting and acting of Sigourney Weaver, whose victory was at least a genuine surprise, dramaturgically speaking. Long before academics started theorizing about the “Final Girl” in horror movies, Ellen Ripley’s fortunate resourcefulness—you gotta be good to be lucky and vice versa—punctured the alpha-male pecking order of action cinema.

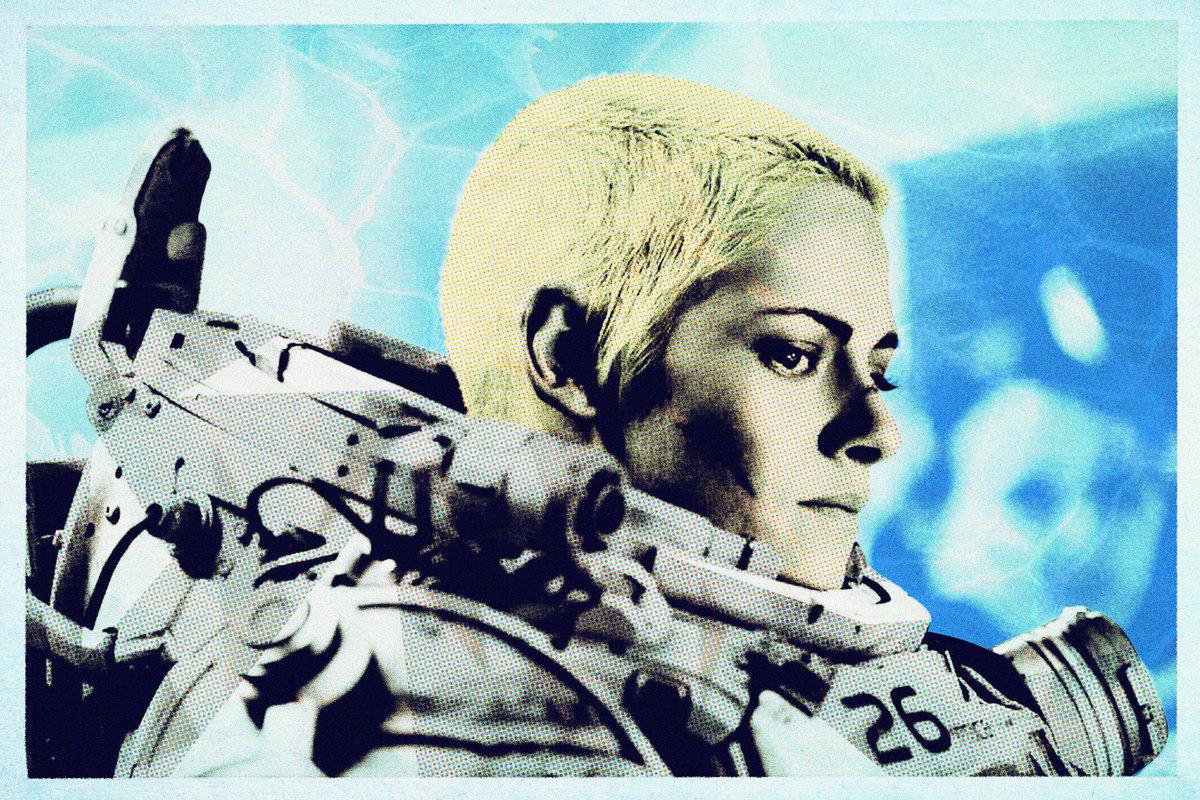

There’s no doubt that Kristen Stewart has been styled to evoke Weaver as Ripley in Underwater, to the point of collapsing the character’s various incarnations into one package: She’s got close-cropped hair (shades of Alien 3), carries a big gun (á la Aliens), and spends a significant amount of time running around in her underwear (as in the climax of Alien), all while projecting the same terse toughness as her inspiration. One of Underwater’s only novelties is the sight of Stewart in her first action-heroine role (like a tree falling in the forest, Charlie’s Angels didn’t happen and you can’t prove it). Her character, Norah, isn’t as well sketched as Ripley (an understatement), giving Stewart only a few opportunities to express her trademark nerviness.

Long before Underwater shows its hand as a creature feature, it tries—in generic but earnest ways—to deal with the idea of contents under pressure, of the psychology that comes with living and working so far from the surface and the sun. And if there’s one thing Stewart can sell, it’s inwardness—the feeling that she’s eating herself up from the inside.

In a more patient movie, the contrast between Norah’s anxious reticence and the (predictably) variegated behaviors of her comrades—the stoic captain (Vincent Cassel); the flighty grad student (Jessica Henwick); the comic relief (T.J. Miller)—would be allowed to develop, but Underwater is in a rush to get started. Before we’ve met everybody, they’re fighting for their lives in the aftermath of an earthquake that significantly damages their rig and engages some life-or-death problem-solving skills.

Director William Eubank (The Signal) tries to solve the problem of staging ensemble drama in cramped quarters by leaning into the claustrophobia, shooting endless close-ups, which unfortunately succeeds mostly in confusing our sense of onscreen space. Even while the dialogue explains where the characters are and where they have to go in order to hitch a ride topside, the geography feels jumbled. At the same time, Bojan Bazelli’s cinematography is extraordinary in its different gradations of metal and murk; shooting in low, exclusively artificial light, he evokes our primal fears of something legitimately vast and bottomless—the ocean as its own galaxy.

Inevitably, our heroes come across a strange, grotesque life form that means to do them harm, and while Eubank deserves a bit of credit for dragging out the reveal of the monster’s actual dimensions and appearance until almost an hour into a 95-minute movie, the thing(s) themselves are a letdown (with none of the personality of, say, Crawl’s CGI alligators or even the resilient little critter in 2017’s Alien rip-off, Life). An extended sequence in which Norah becomes separated from the group offers some relatively well-choreographed stalk-and-swim shenanigans, except that the lack of star power in the film outside of Stewart offsets any possibility that her character could bite it. The reason Ripley’s survival in Alien was so satisfying is because she wasn’t being played by a top-billed movie star: She was a legitimate underdog. Here, Stewart’s celebrity outstrips the rest of the actors put together, and because Eubanks is so committed to delivering the goods, he doesn’t dare the kind of Executive Decision/Triple Frontier maneuver that takes a famous performer out earlier than expected.

There is, I suppose, one late revelation in Underwater that lands—nothing we haven’t seen before, but again, thanks to Bazelli and his ability to integrate special effects into his cinematography, it has an uncommon scale and menace. (Without offering spoilers, I’ll say I thought of Frank Darabont’s killer Stephen King adaptation The Mist, which eventually embraces its Lovecraftian heritage in a big old bear hug.) There are a few breathtaking shots that not only justify Underwater’s existence but also the idea of seeing it in a theater, because otherwise there’s not much separating it from straight-to-Netflix dreck like The Cloverfield Paradox, or the cycle of Alien-but-underwater movies that proliferated at the end of the 1980s (DeepStar Six and Leviathan, both of which are more fun than you remember). As for Stewart, she’ll hopefully get a chance to carry something big and shiny that’s also less perfunctory, because her boredom during Underwater is palpable. It’s only when Norah has to decide whether or not to blow the whole thing up that the actress looks engaged. Hmm, wonder why?

Adam Nayman is a film critic, teacher, and author based in Toronto; his book The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is available now from Abrams.