When the Knicks fired coach David Fizdale back in early December, it seemed like a move that wasn’t likely to alter much about the team. No, Fizdale hadn’t covered himself in glory in Gotham, racking up a 21-83 record that stands as the worst winning percentage of any coach in franchise history. But the Knicks’ hastily constructed backup plan of a roster had, to that point, produced the league’s worst offense, net rating, and record. Could anyone really expect a coaching change to make a significant difference?

Well, the jury’s still out on how “significant” this is, but the Knicks have responded well to a new way of doing things under interim coach Mike Miller, best known to NBA audiences as “Not That Mike Miller.” After winning four games in 22 tries under Fizdale, New York has gone 6-6 since the former G League coach took over, and is currently riding its first three-game winning streak since 2018. Over the past four weeks, everyone’s favorite laughingstock punching bag has been downright average, mostly competent, and reasonably respectable. The Knicks have been—dare I say it?—a pretty normal NBA team.

Miller, a 55-year-old coaching lifer who spent nearly a quarter-century in the college ranks before getting a shot in the pros, doesn’t appear to have done anything drastic or revolutionary to reshape the Knicks. Sometimes simple tweaks can be very helpful, though. (As can a schedule featuring games against the Warriors, Kings, Wizards, Hawks, Nets, and Trail Blazers, all of whom have been reeling for one reason or another.)

One important adjustment the Knicks have made recently: standing in the right places more often. Which, as it turns out, is pretty important.

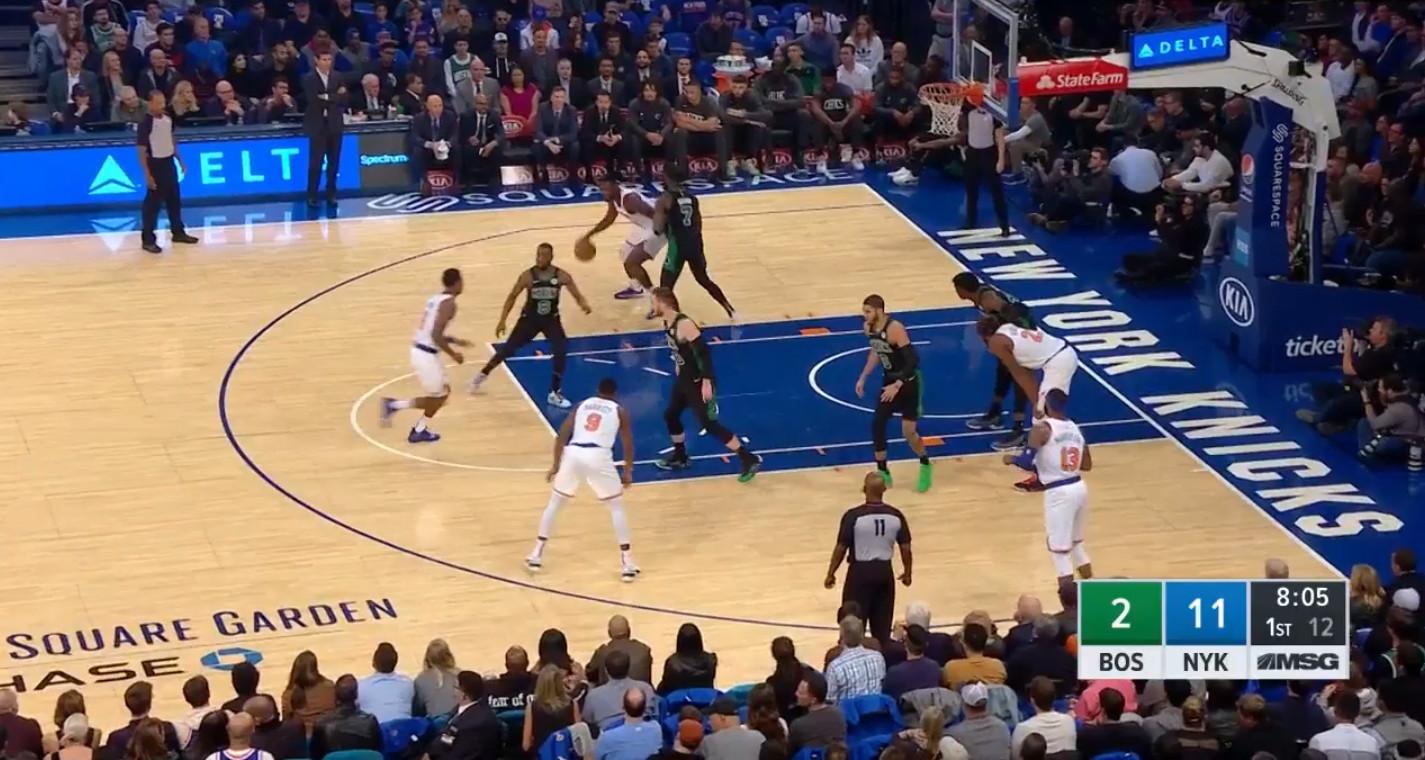

If you tuned in to a Knicks game at some point during the opening month of the season, there’s a decent chance you saw an offensive possession that resembled a five-car pile-up on the FDR during rush hour—just a mess of Knicks all trying to occupy the same space, surrounded by defenders eager to oblige them.

You won’t confuse the latter-day Knicks with the Seven Seconds or Less Suns, but the team has definitely seemed to focus on improving its spacing of late. Miller’s coaching the same roster that Fizdale did, one extremely light on legitimate 3-point shooting threats. Maybe opponents would sag off of New York’s nonshooters to clog the lane no matter what. But the Knicks didn’t have to help them do it; they could, theoretically, stand outside the 3-point line, and see whether defenses might guard them out there. You know, out of muscle memory, or force of habit.

And sometimes they do! Spreading out around the perimeter can draw defenders away from the paint, which can open up driving lanes, room to cut, and opportunities for slash-and-kick passes to create cleaner 3-point looks—all of which can help a struggling offense find some easy money.

Playing in more space has done wonders, in particular, for Julius Randle. The Knicks gave the 25-year-old forward a three-year, $62.1 million contract in free agency, but he struggled with the weight of being a no. 1 option in the early going, posting dismal 44/24/66 shooting splits, committing turnovers nearly as often as he delivered assists, and generally looking ill-equipped to serve as a primary initiator for a functioning NBA offense. (It got so bad that Randle apologized to his teammates during a players-only meeting hours before Fizdale’s firing.) With a less congested court, and with a steadier diet of touches from the elbows and in screening action rather than in isolation in the post or up top, Randle has started to look dangerous again:

Randle’s averaging 22.6 points, 9.9 rebounds, and 2.9 assists per game over his past 12 games, driving to the rim more frequently and effectively against defenses that are more spread out and less able to load up on his downhill attacks. The threat of those rumbles leads defenses to play off of Randle on the perimeter, making a career 30.5 percent 3-point shooter prove that he can make them pay for it. He’s been doing just that recently, making multiple 3s in six of New York’s past 12 games (he’d done it just five times in the first 22) and knocking them down at a 37.7 percent clip. When Fizdale was fired, the Knicks were dead last in non-garbage-time offensive efficiency, according to Cleaning the Glass. In the month since? They’re up to 17th, thanks in part to Randle’s recent surge.

New York has risen up the defensive rankings, too. Once again, there’s a pretty simple tweak behind the newfound stability.

Only three teams gave up more 3-point shots than the Knicks did under Fizdale: the Bucks, Raptors, and Heat. But while those three teams all ranked in the top 10 in defensive efficiency at the time of Fizdale’s firing, the Knicks ranked 23rd, because they also stunk at preventing point-blank shots (21st in at-rim frequency) and at forcing opponents to take lower-percentage looks between the rim and the arc (only Chicago induced fewer midrange attempts). Since Miller took over, though, the Knicks have looked more like a modern NBA team with a plan for getting stops—or, more to the point, a team with one plan for how to do it.

Fizdale liked to dial up different coverages for different opponents, calling for his Knicks to aggressively trap ball handlers in the pick-and-roll, drop back into a soft coverage, switch every screen, and lean on different zone looks from game to game, or even within games. There’s something to be said for defensive versatility, especially for veteran rosters with the savvy, experience, and continuity to understand how to play together in different contexts. For a Knicks roster made up of youngsters still learning the ropes and veterans who just got here, the full suite of defensive options was overkill, leading to frequent breakdowns and disastrous results ... like the consecutive losses by a combined 81 points that led to Fizdale’s ouster.

Under Miller—whose Westchester Knicks teams finished in the top four in the G League in defensive efficiency three times in his four years at the helm—New York has moved more frequently to straight-forward drop coverage against pick-and-rolls. It’s an approach that makes a ton of sense, given New York’s personnel. Point guards Elfrid Payton and Frank Ntilikina are both big, long, and capable of harassing ball handlers from behind with “rear-view” contests. Taj Gibson’s a smart positional defender well-versed in the multitasking required to mind his rim-rolling counterpart while also deterring dribble penetration. Mitchell Robinson is an überathletic shot-blocking behemoth with a condor’s wingspan who can panic drivers on every foray into the paint. Young wings like RJ Barrett and Kevin Knox, who have the size and athleticism to influence plays, get to focus more on just trying to execute one or two things well and worry less about trying to remember a dozen different responsibilities.

The more basic coverage has allowed the players to react rather than think, and the defense has benefited. New York’s getting better at walling off the paint, whether by forcing kickout passes that can stifle possessions …

… or by funneling drivers into a waiting rim protector.

Over the past four weeks, only the Nets, Bucks, and Magic are conceding fewer shots at the rim than the Knicks, and only five teams are coaxing more midrange jumpers. New York’s still allowing 3s at one of the NBA’s highest rates, but they’re giving up high-value corner 3s less frequently. Without a major roster shake-up, the Knicks have gone from one of the league’s worst defensive shot profiles to one of its best, rising to 12th in the NBA in defensive efficiency over the past dozen games largely by, as Randle recently put it to reporters, “not overcomplicating anything.”

The streamlined system has helped unleash Robinson, who was the brightest spot of the Knicks’ woebegone 2018-19 season, and who seemed poised for a breakout this year … if he could just stop fouling. He hasn’t stopped, but he has slowed down over the past month—a development that began just before Fizdale’s exit. (According to Mike Vorkunov of The Athletic, the former coach started penalizing his young center by making him run sprints for every ticky-tack reach-in foul he committed, and Robinson started complying, because “who wants to keep running all day in practice?”)

The trend has continued under Miller, with the second-year big man committing 41 fouls in 303 minutes over his past 12 games, which works out to 4.9 fouls per 36 minutes of floor time. That’s still higher than the Knicks would probably like, but it’s a marked improvement from the 6.1-per-36 he’d managed through his first 18 appearances this season. Fewer fouls means more court time, and as Robinson’s minutes have risen, so has his impact on the game.

The 21-year-old is still learning some of the finer points of interior defense—how to stay alert on the help side, how to avoid getting lulled to sleep by a crafty creator with a nasty hesitation dribble—but he’s already an elite force in the middle. When Robinson is on the court, Knicks opponents attempt shots at the rim less frequently, and much less successfully. They shoot 54.9 percent within 4 feet of the basket when he’s in the game, which puts him in the 95th percentile among all NBA big men, according to Cleaning the Glass. And New York gets torched at the tin when he’s not in, allowing opponents to shoot 67.4 percent on up-close tries.

Robinson is making his presence felt offensively, too, especially as a partner for Payton and Ntilikina in the two-man game. The 7-foot 240-pounder is an absolute monster rolling to the rim, producing 1.67 points per possession as the roll man and shooting 83.6 percent on those plays, which places him in the 99th percentile of pick-and-roll finishers, according to Synergy Sports’ game charting. He’s a holy terror in the air, finishing damn near everything he gets his hands on, and doing so very loudly:

Give Robinson a free run to the rim and it’s an almost guaranteed two points. Commit too hard, though, and you risk putting the defense in rotation and giving up a wide-open look elsewhere. That roll gravity doesn’t show up in Robinson’s box score numbers, but it’s real; there’s a reason the Knicks have scored 113.1 points per 100 possessions with Robinson on the court during Miller’s tenure, and just 99 points-per-100 with him on the bench. (Which is where he still is at the start of games, for the moment.)

He’s still averaging only 25.3 minutes per game since the coaching change, but it’s getting hard to ignore Robinson’s potential. He’s got the best plus-minus on the team during this .500 stretch. FiveThirtyEight’s RAPTOR player rating metric grades Robinson as the only Knick who’s a net positive on both ends of the court. And he just turned in the best game of his young career, pouring in 22 points on perfect 11-for-11 shooting with eight rebounds, a steal, and a block in 27 minutes in a blowout win over Portland on Wednesday. The performance drew praise from someone who has authored a few memorable outings of his own at Madison Square Garden over the years.

“I don’t really think [Robinson] understands how good he is, or how good he can be, his ceiling,” Blazers forward Carmelo Anthony told reporters after the Knicks’ win. “The way he plays is perfect for what the Knicks do.”

Provided, of course, the Knicks keep doing it. Miller is, after all, an interim coach; it’s unclear whether team president Steve Mills and general manager Scott Perry will get to helm another coaching search, but it’s unlikely that Miller will get the nod to keep running the team. The roster that Miller (or his eventual successor) has to work with could soon change, too, with rumblings that some Knicks would prefer to be shipped elsewhere before the February 6 trade deadline. And with the schedule about to take a turn for the brutal—a four-game West Coast road trip featuring meetings with the Clippers, Lakers, and red-hot Jazz, followed shortly by meetings with the Heat, Bucks, and 76ers—the good vibes from a .500 month might not stick around too long.

Even if this brush with blissful mediocrity turns out to be short-lived, it’s worth noting and remembering why it happened: In the midst of the ever-roiling circus that is life at Madison Square Garden, someone reminded the players where to stand and what not to worry about. That’s it. That’s all it can take not to suck. It’s truly wild that the capacity to get those simple things right—to even create an environment in which they might be able to happen—has eluded the Knicks for the better part of two decades. But it doesn’t have to forever.