It’s staggering to think that Zion Williamson, at just 18 years old, is already a legendary athlete. Whatever he lacks in experience and rings he makes up for in sheer folklore quotient (something I made up, just now: FQ). Zion has leaped into the ranks of Bo Jackson, Earl “the Goat” Manigault, Jim Thorpe, Steph Curry, Deion Sanders, Wilt Chamberlain, and André the Giant.

To have a remarkable FQ, an athlete must pass this test: One of their plays inspires a story that sounds like a tall tale. One of the most famous examples in basketball is the story of playground legend Manigault making change on the top of a backboard. The story’s been debunked, but that it’s plausible enough to investigate signifies an epic folklore quotient. The key to registering on the FQ scale is that someone hears an implausible story about an athlete but can’t definitively convince themselves that it didn’t happen. Just check out Williamson’s coast-to-coast movement against Louisville from earlier this week.

How would you even describe that if you didn’t have an endless highlight reel to point to? Zion has immense FQ potential because he is [extreme Architect from The Matrix Reloaded voice] an anomaly. Some might say that he shouldn’t be playing college basketball at all (pointing at myself right now), but it took only a handful of games for it to become abundantly clear that we’re not just dealing with a walking, talking highlight mixtape. We’re dealing with a young player who could have a dramatic impact in the NBA in some very nuanced ways.

As wannabe historians, we’ve done our best to compare him to past players, but because of his outlier combo of build and explosiveness, we’ve been left in a state similar to that of his college opponents this season: off-balance and reeling.

Zion’s dunks are the lowest type of hanging fruit for the casual basketball fan, but even the smarmiest hoop nerds become giddy schoolchildren when Zion pro-hops 10 feet to split an eager double-team and hit an open shooter. (This didn’t actually happen, but you weren’t sure! FQ!) They melt when he one-step leaps into the stratosphere to snatch a seemingly unattainable rebound. I actually catch myself getting up off the couch when there’s a live-ball turnover in his vicinity. There are unprecedented amounts of available oxygen when it looks like Zion has an open path to the spectacular.

I love a good breakaway as much as the next person, but Zion truly finds separation from his peers in moments of contact/explosion. Years ago, before player movement was really policed, teams would likely have just beaten the shit out of Zion. Today, it’s not so simple.

Funneling a player of his size and agility to an advantageous position these days is like trying to play a perfect game of Operation after throwing back eight espresso shots. It’s one thing to have time to gather yourself and challenge what Zion can do (you can’t), but it’s another to challenge and absorb the graceful power that he operates with off the dribble. In that moment when you’ve brushed against his 285-pound frame, you’re trying to maintain your balance while also attempting to contain him as a ball handler, and then you’ve got to be prepared to contest some of the most abnormally explosive finishing that basketball has ever seen.

Also, you bum, could you also do everyone a favor and not foul? Not since 2007 LeBron have we seen an athlete this peerless in basketball. Not in high school, not in the college game, not in the NBA. Basketball.

Of all the phases of the game, I would posit that Zion is most devastating on the defensive glass or on forced turnovers, because of what follows. As the infatuation with the 3 pervades basketball worldwide, Zion’s value grows, and it has nothing to do with his shooting.

In a transition sequence, Zion can play any part and blow the doors off of the defense, and the pressure his presence puts on the opponent brings heavy gravitational pull in his direction. In one play, he can make the incredible corrective defensive play, grab the out-of-area rebound (it’s to the point where we should just stop calling them “out of area”), laterally explode, put the entire defense on its heels, and get into transition with an outlet or hit-ahead pass. He can very capably navigate dense traffic as a ball handler and find shooters running wide who are benefiting from his gravity.

And he can, as we know, go for the ridiculous finish. You knew Zion could dunk, right? Should I go into that? You’re acting like you’ve heard that part. Cool.

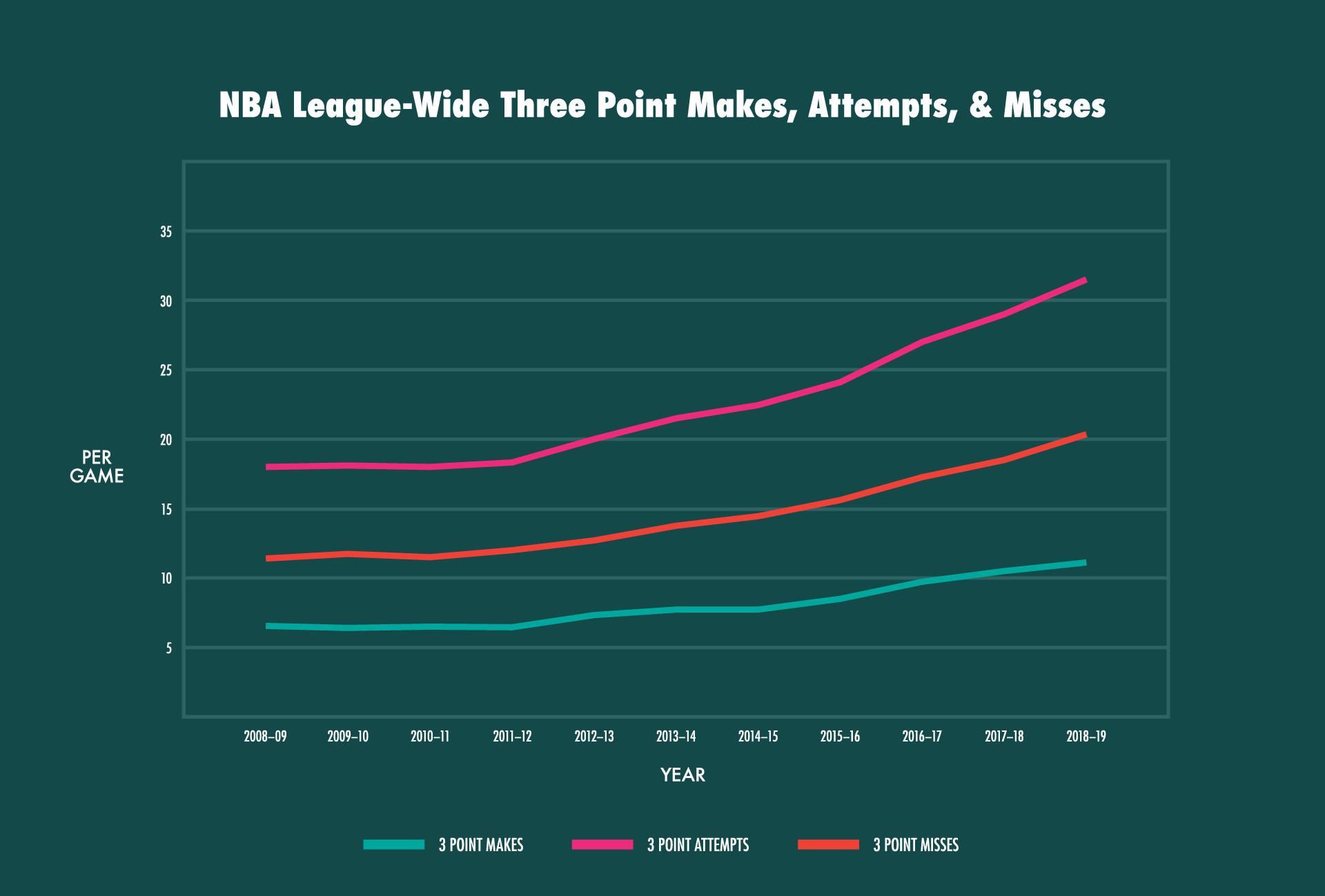

This versatility and potency in transition is a big reason Zion will be so valuable in the NBA. He’ll likely need to play with a lengthy stretch big who has some modicum of rim-protection capabilities (cough, KD). But as 3-point attempts climb leaguewide, so will the volume of misses and, subsequently, higher and longer rebounds. That means 20 or more transition opportunities a game during which Zion’s team will have an ace in their hand, regardless of where he is in the transition sequence. What will that number be in 2029? 35 to 40?

This season, he’s averaged 1.329 points per possession in transition (89th percentile), according to Synergy. Because Duke does not have a glut of versatile or consistent 3-point shooters, I suspect that we’re seeing only the beginning of how devastating Zion-on-the-run could be. Cam Reddish is the closest thing Duke has to a dynamic outside shooter, and he’s shooting 35 percent. Duke rates at 306th in the country in 3-point percentage and tied for 109th in attempts. Imagine if Zion were playing on a roster that could’ve forecasted his role at the next level. It’s easy to get carried away imagining how much his spatial advantages will improve in the NBA.

Duke’s lack of shooting has also played a part in depriving us of Zion as a screener and short-roll creator. Can you imagine him running Spain pick-and-rolls with Trae Young and Kevin Huerter? Do you need a glass of water?

Another overlooked effect that Williamson’s athleticism has on the game is the amount of time that he can buy Duke’s defense. Physical outliers like Zion give the offensive player a moment of “… oh no.” His presence creates a persistent sense of uncertainty. It disrupts the offensive player’s comfort level and causes second-guessing. Those moments are precious to a team defense, and they give the opportunity to recover. Even scarier: Zion’s defensive positional intelligence has trended up during the season, so the seemingly obvious counter of “just shot-fake him!” seems less and less like an effective strategy.

Ever since Sports-Reference began keeping stats, no player has soared to the heights (cannot escape the leaping puns) that Zion has in PER, win shares per 40 minutes, offensive box plus/minus, and box plus/minus. Specifically, in PER, the gap between Zion and the next person on the list is greater than any gap between slots in the top 10. This is some damn near Secretariat-level galloping away from the pack.

Zion’s value and development in the half court have been absolutely mind-melting this season, far exceeding anyone’s honest expectations. He rates above the 90th percentile in offensive rebounding, ISOs, post-ups, and even excels as the ball handler in the pick-and-roll, albeit in a small sample. There are just so, so many ways that this kid’s game could grow, and even without major development in those areas, Williamson is rightfully being pegged as one of the most exciting prospects in recent memory. Years from now, when we’re passing around stories of this excitement, it’ll be fun to watch people attempt to separate folklore from reality—because the reality of Zion Williamson is that hard to believe.