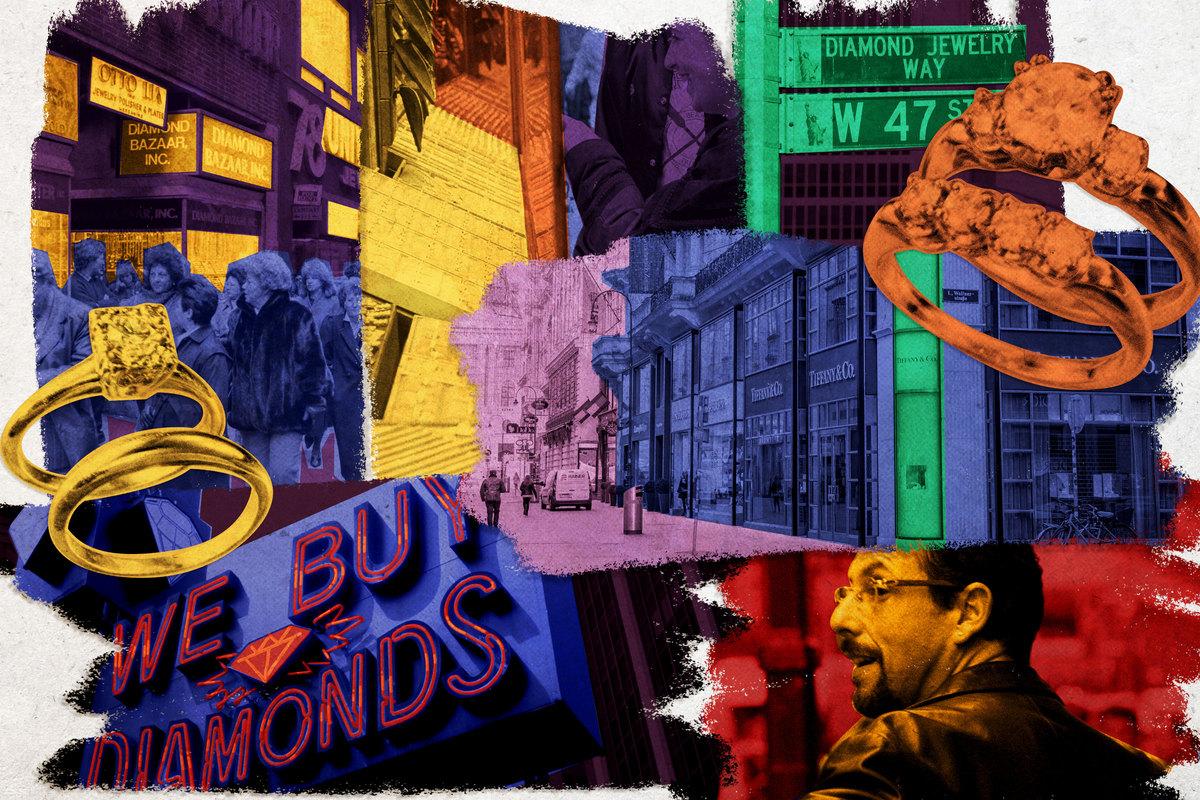

Inside the Diamond District, the Grimy, Shiny Setting of ‘Uncut Gems’

Directors Josh and Benny Safdie spent a decade researching their new film, ample time to embed themselves in one of New York City’s most distinct neighborhoods. Ahead of the movie’s release, The Ringer spoke with actual diamond district jewelers about the movie’s real-life inspiration.

In Josh and Benny Safdie’s Uncut Gems, Adam Sandler plays Howard Ratner, a jeweler navigating midtown Manhattan’s diamond district in 2012. Howard is an incorrigible wheeler-dealer, amphetamine teeth-grinding made flesh, and Sandler clambers through New York like he was born to lowball customers and make horrible choices. However, while the Safdies always dreamed of Sandler as their lead, he wasn’t originally slated to play the role—Jonah Hill, Harvey Keitel, and Sacha Baron Cohen all came up as possible stars during Gems’ lengthy preproduction process, a decade-long journey of promising starts and frustrating stops. But the extended incubation period did have a major upside: It allowed the Safdies ample time to immerse themselves in the world they wanted to portray.

“The Safdie brothers had spent the better portion of 10 years trying to get the movie made, and in the process had also really, really embedded themselves in the diamond district,” Uncut Gems production designer and longtime Safdie collaborator Sam Lisenco tells The Ringer. “It’s a really closed-off and insular community that does not welcome outsiders. It took Josh, in particular, a good couple of years to get to a place where they were comfortable enough to let him take photos of spaces, let alone to start bringing in his designer.”

The diamond district is a blingy labyrinth of sellers, traders, appraisers, and schemers on 47th Street in Manhattan, between Fifth and Sixth avenues. It’s a five-minute walk from 30 Rock, Trump Tower, and the ritzy shops on Fifth Avenue, but it feels extremely separate, like time-traveling back to a far less corporatized, pre-Giuliani version of the city. Crabby hawkers mutter about deals on the sidewalks; storefronts are cluttered with watches and gold chains and blinding tennis bracelets below neon signs; decrepit-looking stairs leading to pawn shops are nestled between gem exchanges where weary workers hunch over desks behind thick Plexiglas, squinting to examine tiny stones; under the ever-present scaffolding, Hasidic men stop to chat with Russian men who just finished clasping hands with Indian men as armed guards look on; there aren’t very many women, and everybody smokes. It’s not all seedy—the Gemological Institute of America, better known as GIA and located inside a shiny skyscraper on the block, is considered the industry standard-bearer for appraisal. And while many of the street-level vendor spaces are worn down, there are billions of dollars worth of products in the vaults on the higher floors.

“The real action is upstairs,” says Eric Mor, the co-owner of Abe Mor Diamond Cutters, located on the fourth floor of one of the street’s tall buildings. In Uncut Gems, Howard’s office is similarly located on a higher floor, with a nondescript hallway leading to a forbidding, high-security door featuring cameras and buzzers. “There were about four or five different shops that we pulled specific details from,” Lisenco says. “We wanted it to look a little outmoded. Even then, even in 2012, it would still kind of feel like it needed a refresh.”

Mor’s shop isn’t ostentatious or newly updated—there’s standard-issue office furniture and a handful of magazines in the sparse waiting room—but its details betray the unusual particulars of its trade. Just as in Uncut Gems, you have to be buzzed inside (although Mor’s space is much larger). There are framed posters of Eric’s father, Abe, cutting diamonds in Israel, the beginnings of the family business. He looks very young. “My dad’s 83. He’s been doing it since he was 13,” Mor explains, noting that his father had entered into an apprenticeship instead of going to high school. And within Abe’s office, the company’s vaults hold a startlingly expensive array of diamonds and other jewels—most purchased secondhand, as the father and son specialize in antique and vintage offerings. Mid-conversation, Mor takes out a canary diamond ring, big and yellow and so sparkly it almost looks fake, with a band of spectacular small diamonds. As I hold it between my fingers, he tells me the price: “It retails for $200,000.”

Deciding that actually slipping the ring onto my finger might turn me into a Lord of the Rings–style diamond monster, I quickly hand it back.

When he’s not placing increasingly reckless sports bets in Uncut Gems, Howard caters to celebrity clientele from his dingy-yet-high-security shop, including Kevin Garnett, who yearns for the titular uncut gem. The coveted object was hard to get right. “We had some problems with the gem throughout the movie. We could never get it to satisfy what we all wanted it to be in some way,” Lisenco says. “You have to make this rock look magical. And it’s more about how people react to it rather than the object itself.”

All of the jewelers I spoke with stressed that buying a gigantic uncut gem is a wild thing to do. “When you have an uncut gem, you don’t really know what’s going to come out of it,” Mor says. Diamond expert Michael Fried, who currently works in Europe but spent his early years on 47th Street, sees it as an act of cockeyed optimism. “People might be willing to trade in uncut diamonds because there’s this potential,” he says. “They have this illusion that they can make it this masterpiece.”

The would-be masterpiece in the movie went through different iterations. “We flew in chunks of real opals from all over the earth. A lot of real black opals from South Africa,” Lisenco says. They arranged these small rocks to look like they were part of one much larger rock, since a real uncut gem of that size was way out of the film’s budget. However, it was still a costly accessory: Lisenco estimates that there were “probably 20 to 30 thousand dollars’ worth of real opal chunks throughout the movie in that prop.” For many of the rows of jewels shown in the backgrounds of shots or beneath Howard’s glass, the production design team chose a more affordable path. “A lot of it was costume, a lot of it was cubic zirconia,” Lisenco says. The movie’s famously sparkly Furbies, alas, were not blinged-out with real jewels. “Yeah, those were also zirconia.”

At the beginning of the film, Howard excavates the uncut gem from a dead fish’s belly, a memorably disgusting and sneaky moment, and an example of an invented Safdie flourish. None of the jewelers I spoke to had ever heard of people hiding expensive rocks in fish, nor did any recommend it. “You don’t want to mess with importing diamonds that are not legal,” Mor said. “There’s very strict rules.” Fried found it to be outside his own experience—but not entirely implausible. “I would not be surprised if people are smuggling things in different ways,” he said. “I think I would just fly it over instead of just sending it through a fish and using other people. But that definitely makes a good movie plot.”

According to Lisenco, the scene was a nod to the brothers’ upbringing that had survived the film’s many iterations, rather than anything culled from life. “In the 10 years that they’ve been working on this movie, it was different characters who brought in the fish so many different times. But it was always smuggled in in a fish,” he says. “Part of that is a little shout-out to their dad, who worked in both the diamond world and fish world for a little while.”

While the entire diamond district serves as the movie’s setting, the store Avianne and Co. Jewelers, known for its celebrity clientele and cheeky custom designers, is a clear source of inspiration. Its recent Slimer piece, for example, is clearly a spiritual sibling to the swaggy Furbies in Uncut Gems.

Joseph Aranbayev, a co-owner who uses the name Joe Avianne professionally, says that the Safdies took photographs from Avianne and edited them to look like Howard’s photos, then used them on set. “They just took those pictures, edited out all our faces, and put Sandler’s face there,” he says. What’s more, Joe says Sandler’s performance as Howard was the result of studying Avianne’s staff. “Adam Sandler was here for a few months, learning from my brother Izzy on how to buy and sell diamonds, and just in general how to be a diamond dealer,” Avianne says, noting that the rapper Cam’ron had made the introduction. “There’s a certain way you open the parcel before the diamonds fly out everywhere, right?” he says. According to Avianne, Sandler’s careful attention made his performance more precise. “There’s a certain way you hold a stone with the tweezer. There’s a certain way you have to hold the loupe. You know, these are things that he does in the movie. So in order for him to do it in the movie, he has to have practice. And how does he have practice? He has to go to somebody who knows how to do this for a living. So he learned from us.”

The result of all of this prolonged and careful study is a dark but loving homage to one of Manhattan’s oddest pockets. Howard’s world is garish, precarious, and populated with a cast of loudmouths and menaces that should feel cartoonish but always feels real—a testament to the breadth of research from the cast and crew, and their obvious affection for a part of the city that is often disparaged or overlooked.

Before I leave, Avianne excitedly mentions that his 15-year-old nephew, Jonathan Aranbayev, was actually cast as Howard’s son, Eddie, after being discovered in the shop. “They saw him here, and they just liked his personality,” he says. At this point, Joseph FaceTimes Jonathan, who’s in Los Angeles for the Uncut Gems premiere. “This lady is doing an interview about Uncut Gems,” Joe says to Jonathan, who’s very polite. He shows me what he’ll be wearing to the premiere—an enormous diamond-encrusted piece that says “Uncut Gems.” Inspiration can be a two-way street, lined with jewels.