The week before MLB’s annual winter meetings, which will begin in San Diego on Sunday, brought both bad news and good news for fans searching for signs of resurgent spending on the sport’s free-agent market.

In the wake of consecutive slow-motion offseasons, an unprecedented second straight decline in MLB’s Opening Day average salary (amid rising revenues), a rash of spring extensions that seemed to stem in part from players’ reluctance to test the unwelcoming market, and continued tension and public posturing between the league and the MLB Players Association in advance of the CBA’s December 1, 2021, expiration date, this winter was set up to be a bellwether of labor peace or strife. In July, union head Tony Clark said the players would be seeking a return to “meaningful free agency,” and some signings announced this November and early December have hearkened back to the halcyon days when the union could count on big contracts for veterans with several seasons of service time boosting players’ average earnings. Even so, the underlying conditions that have destabilized the sport’s traditional salary structure still seem to be in place, which means that the threat of a work stoppage remains in effect.

Let’s start with this week’s sign of a spending apocalypse. Teams declined to tender contracts to 55 arbitration-eligible players on Monday’s non-tender deadline, including six players who were worth at least one win above replacement player in 2019 (Yolmer Sánchez, C.J. Cron, Junior Guerra, César Hernández, Tim Beckham, and Kevin Pillar). That marked the most non-tenders in any offseason since at least 2008, and the highest percentage of arbitration-eligible players for whom MLB Trade Rumors had projected arbitration salaries non-tendered since at least 2010, the year before MLBTR began providing its projections.

Granted, there have been other offseasons when teams chose to non-tender players who produced even more combined WARP during the preceding season. None of the newly non-tendered players projected to be impact players in 2020, so in most cases, it’s understandable that teams didn’t put a premium on keeping them around. However, it’s still a possible sign of the shift in team spending patterns that has made free agency less lucrative. In previous years, teams might have brought back some of those arb-eligible players even though they weren’t all that special statistically. In the era of breakout batters and precocious superstars, though, teams are more confident that they can replace non-elite players with less expensive alternatives promoted from within or plucked off the scrap heap and equipped with a new pitch or a revamped swing. Teams no longer prize or pay for experience, as many free agents have found out.

Along the same lines, the Orioles raised eyebrows a few days before the non-tender deadline by placing Jonathan Villar on waivers and subsequently trading him to the Marlins for Miami’s 2019 14th-round draft pick, left-hander Easton Lucas. Villar led Baltimore’s lowly 54-win team with 4.0 FanGraphs WAR in 2019, yet the Orioles elected to trade him rather than pay him a projected $10.4 million in his final year of arbitration. That decision by Orioles GM (and ex-Astros AGM) Mike Elias smacks of Astrosesque rebuilding behavior: The 2020 Orioles are going to be bad with or without Villar, who somewhat overperformed his peripherals this past season, projects to be half as valuable next season, and doesn’t have the star power to sell tickets. Couple that with the $99 million the Orioles owe the Nationals for shortchanging them on MASN TV rights from 2012 to 2016, and one starts to see why a regime with a history of tanking might consider him expendable.

Again, though, this is a choice the franchise might not have made in an earlier era, before revenue sharing, income from TV contracts and spinoff sales, the Astros’ and Cubs’ high-profile rebuilds, and skyrocketing franchise valuations made an explicit strategy of short-term non-contention more palatable and helped enable a historically lopsided league of superteams and temporary pushovers. There’s still a strong correlation between winning and payroll and winning and revenue, but the downside to not spending isn’t as steep as it was when revenue was more dependent on ticket sales. Add the non-tenders and the Villar salary dump to the chorus of owners and front-office executives bemoaning “budget limitations” and expressing a desire to keep their payrolls beneath baseball’s overblown competitive balance tax threshold, and the prognosis starts to seem grim. In February, Elias told The New York Times that teams can “maintain a long, competitive state by having a quality organization, drafting well, making shrewd decisions, and not making emotional, irresponsible decisions when it comes to free agents or extensions.” Or, in other words, by not investing heavily in high-priced, depreciating veterans as they did for the first 40 or so years of free agency.

Yet amid that fan-repelling rhetoric, we’ve seen several teams spring for free agents whose contracts have looked like throwbacks to winters when the stove was as warm as advertised. The White Sox signed Yasmani Grandal for four years and $73 million. The Padres signed Drew Pomeranz for four years and $34 million. The Reds signed Mike Moustakas for four years and $64 million. The Phillies signed Zack Wheeler for five years and $118 million, and Wheeler reportedly passed up an even richer offer from the White Sox. José Abreu accepted a $17.8 million qualifying offer from the White Sox, but then the Sox extended him for an additional two years and $32.2 million. Thus far, it seems as though the big-money, longish-term free-agent deal has risen from the ashes.

No, we haven’t entered extremely player-friendly territory; these aren’t the seven-to-10-year bonanzas for 30-something stars that live in free-agency lore. But these commitments are at least in line with or above what one would think these players would be worth. Consider this: From 2014 to 2016, FanGraphs readers predicted the size of free-agent contracts almost perfectly, on the whole, but from 2017 to 2019, as free agency stagnated, they overshot the actual contracts by more than 20 percent.

This year, though, the 13 free agents who have signed after receiving crowdsourced contract predictions from FanGraphs have exceeded those estimates by 25 percent (if we count only Abreu’s qualifying offer) or 33 percent (if we include his extension). Grandal, Wheeler, Moustakas, Pomeranz, and others easily exceeded their expected takes. The only players who’ve earned significantly less than expected are Jake Odorizzi, who accepted the Twins’ qualifying offer, and Cole Hamels, who took a one-year, $18 million deal from the Braves instead of the two-year, $30 million deal the crowd forecasted.

The signings of Moustakas and Grandal are especially notable because those two were among the players who were burned by the free-agent downturn. Moustakas settled for back-to-back one-year deals, although the Kansas City Star’s Sam Mellinger reported that Moustakas had turned down a three-year, $45 million offer from the Angels in 2017, which the Angels and Moustakas’s agent, Scott Boras, denied. Last year, Grandal also resigned himself to a one-year contract, after reportedly turning down a four-year, $60 million offer from the Mets. Those travails may have made them less likely to hold out for pie-in-the-sky offers this time around, which could help explain why they signed so quickly. What’s more, their circumstances have changed: Moustakas had declined a qualifying offer in 2017, as had Grandal last year, and the draft-pick compensation attached to them depressed their earning power. Still, it’s hard to decipher why Moustakas made so much more this year than he did last year: He’s a year older, and he didn’t demonstrate any new skills this past season, save for an ability to play a passable second base. Maybe the Reds just really loved Moustakas, or maybe the market is correcting.

Admittedly, the cumulative luster of these early, prediction-defying signings may reflect the fact that teams move quickly to sign the players they’re most bullish about; players signed later in the offseason tend to earn less, so it’s not as if contracts will keep exceeding pre-offseason estimates by the same margin. Even so, it’s refreshing for the “How much?” reactions that sometimes follow free-agent signings to be about big numbers, not small ones. This recent spate of well-compensated players prompted the Times’ Tyler Kepner to compare the early offseason’s free-agent agreements to deals “signed in the good old days of free agency for the players, an era that just might be back.”

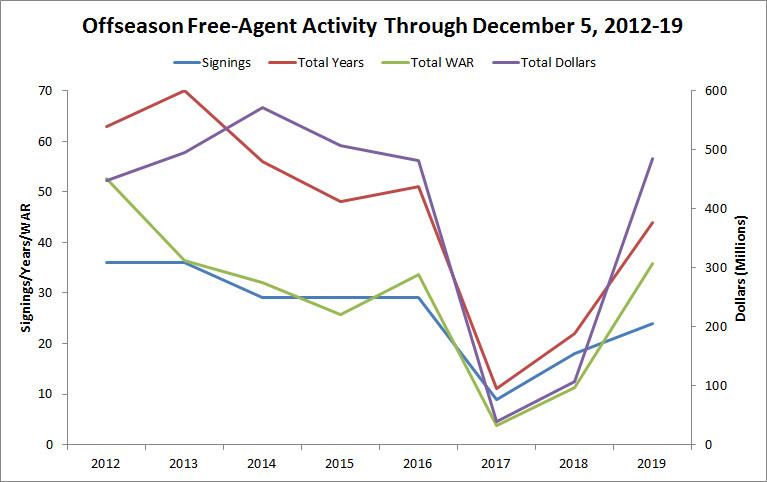

Some of that exuberance may be a response to the slowness of the past two offseasons; after 2017 and 2018, almost any early activity feels like a lot. (Not one of MLBTR’s top 50 free agents signed in November 2017, and only two did by December 5; this year, nine signed in November, and 13 through December 5.) But this year’s perceived bounceback in free-agent spending isn’t an illusion; it really does represent a drastic uptick compared to the recent past. The chart below, based on transaction data from The Baseball Cube, shows the number of free agents signed to major league contracts through each December 5 from 2012 to 2019, as well as the total years and dollars committed to them and the number of FanGraphs WAR they produced in the preceding season.

Relative to the same date in the past several offseasons, we’ve seen significantly more signings, of significantly better players, who’ve collectively commanded much longer and larger contracts. On the eve of the winter meetings, then, it looks like baseball’s frozen free agency has thawed. And the top trio of Boras-repped free agents, who strutted their stuff in the World Series, are still awaiting windfalls that will arrive at some point between now and Opening Day. If the accelerated start to this winter is any indication of transactions to come, maybe Anthony Rendon, Gerrit Cole, and Stephen Strasburg won’t linger as long without a team as Bryce Harper and Manny Machado did last winter.

The question is whether we’ve really seen enough to declare that “the good old days” are back. Given the salary-suppressing prelude to this winter, this could be closer to a dead cat bounce than a true return to the old normal. As encouraging as the rebounds in the image above appear, the number of free-agent signings through December 5, and the years devoted to them, are all lower in 2019 than they were in every offseason from 2012 to 2016. The dollar total, which has soared to almost $500 million, is also lower than most of those years, in spite of inflation and rising revenues. This year has been heartening compared to the past two, but it’s still somewhat underwhelming on a longer timeline.

Moreover, there are some signs that the free-agent spending downturn began before it came obvious, which would raise the bar for believing that free agency is back in full force. The graph below, based on 1989-2019 salary data from eBIS (supplied by an agency source), suggests that teams started cutting back on financial commitments in future seasons before the average current-season salary sank. The red line charts the money that teams paid players in the current year, while the other colored lines display the totals in each season that were already earmarked for the next four seasons.

Zoom in on the period post-2010, and it’s clear that the future commitments—represented by the lines other than the red ones—slowed or plateaued a year or two earlier than the current-season spending. That disguised the impending downturn in average salary until it became the big story of the 2017-18 offseason, but even before then, teams were already avoiding those so-called “emotional, irresponsible decisions” that had long propped up the players’ share of revenue. Clearly, major leaguers’ fortunes have hugely improved in the decades following their winning collusion cases, but MLB’s revenues keep rising, and lately, players’ salaries haven’t kept pace.

Some of the long-term deals dispensed in happier times for free agency will expire in the next few seasons, which may exacerbate the average salary situation. So yes, the start of this offseason has been blessedly busy, and next week may bring many more moves. It’s true that some teams that have sat out earlier offseasons, such as the White Sox, are feeling friskier now: Rebuilds are cyclical, and each winter features a different collection of clubs in win-now mode that have payroll room to spare. Maybe some teams are learning that fiscal efficiency is a poor substitute for a flag. But the root causes of the economic crisis confronting the players have yet to be addressed.

Front offices are increasingly adept at projecting and paying for future production rather than rewarding performance that probably won’t be repeated. Although that benefits a few free agents—teams seem to be betting on improved pitching from Wheeler, and the Padres must be banking on the bullpen version of Pomeranz that the Brewers deployed in a small sample late last season—it doesn’t help them as a whole, because most players have peaked or are heading downhill by the time they reach free agency, particularly in an era when 30-something players are aging less gracefully than before and, consequently, drawing less interest from teams. At a time when rising franchise costs make it difficult for individual bidders to buy baseball teams on their own dime, fewer owners (or ownership groups) operate in the mold of Mike Ilitch or George Steinbrenner, handing out high-dollar deals and disregarding the models that their quants cook up. And improved player development is still driving a higher share of leaguewide WAR toward pre-free agency and pre-arbitration players.

In modern baseball, players with six or more years of service time receive about two-thirds of the players’ overall earnings in exchange for well less than a third of the total on-field value. That’s the structure that the league and the players collectively bargained, and for 40 years, it functioned fine. Now, though, the players have fallen prey to a predicament partly of their own making, one that may persist unless they can force owners to raise minimum salaries or shorten the path to free agency. Rob Manfred may not have been wrong when he reportedly told union negotiators, “Maybe Marvin Miller’s financial system doesn’t work anymore.” Despite the reprieve of the past several weeks, the fight for a permanent restoration of “meaningful free agency” has probably barely begun.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris of Baseball Prospectus, Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference, and Colin Wyers for research assistance.