Last Tuesday, Dodgers right fielder Joc Pederson swung at a pitch just off the outside corner, sliced it toward left field in Petco Park, tossed his bat in disgust at the weak contact … and then circled the bases, because the ball had flown over the fence.

The data didn’t scream “homer” any more than the misleading swing. Pederson’s dinger wasn’t hit very hard (99.8 mph). The average homer has a 28 degree launch angle; this one was significantly steeper, at 41 degrees. Petco Park still suppresses lefty power, and this wasn’t a warm day; 73 degrees at first pitch, and likely cooler by the time Pederson came to the plate in the ninth inning. Pederson’s teammates were still smiling about his initial reaction as he headed toward home plate, but it’s hard to blame him for misjudging the result. Nothing about that batted ball looked like a homer until, out of nowhere, it was one. And sometime in the next month, we might see another “What the hell?” homer at a moment that matters much more.

It’s hard for hitters today to tell what a homer feels like off the bat, because the prerequisites keep changing. When Pederson debuted in 2014, MLB’s home run rate had sunk to its lowest level since 1992. This year, it’s higher than ever; 2019’s total of 6,776 homers surpassed the previous regular-season record by 671. Most of that difference didn’t stem from changes in hitters’ or pitchers’ approaches, or from certain types of batted balls becoming more common. Statcast tells the story: During Pederson’s six-year career, the expected outcomes of batted balls launched with similar speeds and trajectories have varied wildly from year to year, and even month to month.

In 2016, when the home run rate was high but hadn’t quite reached a record level, balls hit like Pederson’s September surprise—between 99 and 101 mph in exit speed, and between 40 and 42 degrees in launch angle—collectively produced a .356 slugging percentage. In 2017, when the home run rate leaped to an all-time high, balls in that same bucket yielded a slugging percentage almost 200 points higher (.554). Last year, when the homer rate receded to 2016-adjacent territory, so did the slugging percentage (.370). But this year, as the homers returned with a vengeance, the slugging percentage exploded to .670, which is more than 300 points higher than 2016’s.

If we further restrict the sample to opposite-field flies only in the same speed and angle ranges as Pederson’s, the contrast is even more stark: Those batted balls produced a .000 slugging percentage in 2015, and a 1.154 slugging percentage this season. Basically, balls hit like Pederson’s went from automatic outs to smashing successes. Compare Pederson’s dinger to this Christian Yelich flyout from just last year: same hitter handedness (and post-swing frustration); roughly the same pitch location and hit direction; exit speed and launch angle within 0.3 mph and 1 degree of each other, respectively. Pederson didn’t hit his ball any better, but it went 13 feet farther, which made all the difference.

So, similar inputs, drastically different outputs. Atmospheric conditions matter, as do batter and pitcher tendencies, but there’s little mystery about the primary cause of the uptick in taters: It’s the ball, which—as an MLB-sponsored panel of engineers, physicists, and statisticians concluded last year—has become much more aerodynamic due to differences in construction that the MLB-sponsored study was unable to pinpoint. Commissioner Rob Manfred admitted last week that the ball has been volatile, saying, “We need to see if we can make some changes that gives [sic] us a more predictable, consistent performance from the baseball.”

Manfred revealed that he’s reconvened the Council of Elrond and commissioned a new report about the one ball to rule them all, which he expects to receive after the World Series. MLB, which bought baseball manufacturer Rawlings last year, may make changes to the ball based on the report’s findings, and those changes may make homers like Pederson’s less likely. For now, though, the deceptive—and, by historical standards, undeserved—dinger is a constant threat. While the ideal home run rate is ultimately a matter of taste, frequent, uncontrolled fluctuations that rewrite the ground rules are probably more of a bug than a feature.

In October, that bug could be game-breaking. We don’t have to rehash all of the effects of the lively ball, which include a cavalcade of home run records, a democratic distribution of dingers, and a corresponding rise in the home run rate in Triple-A, which adopted the MLB ball this year. What we’re here to discuss is cheap dingers, and the potential for fluky, fence-clearing flies to dictate the outcomes of pivotal postseason series. Pederson’s homer happened late in a game that the Dodgers were already winning, with only home-field advantage in the World Series still at stake for his team. Were a similarly ball-dependent dinger to occur at a crucial time in October, though, it could embarrass MLB by swinging a series, slightly tarnishing a team’s victory, and giving fans of the defeated club more reason to be bitter.

Pederson’s solo shot is one example of the “only in 2019”-type homer we’ve seen so often; pick your poison. According to Statcast-based, launch-info-adjusted estimates provided independently by statistician Jim Albert and Baseball Prospectus researcher Rob Arthur, roughly 11 percent of the homers hit this year would not have left the yard had the 2019 ball been replaced by the 2018 ball. In 2017, when the home run rate was lower than it is now, teams combined to blast 104 homers in the playoffs. If the playoff field were to produce the same number of homers this year, we would expect roughly 11 of them to be balls that would not have gone out had those hitters made identical contact in 2018. Any one of those gifts from the gods of reduced drag could clinch a series and send someone home. Starting the winter would sting even more for the vanquished if it didn’t really look like the victor had earned his RBI.

The ball-assisted homer is an unearned run not in the scorekeeping sense, but in the narrative sense. Every game and series tells a story, and those stories aren’t as satisfying when they end with everyone asking, “How did that get out?” Granted, every team has to play with the same lively ball, so it’s not as if only one side stands to benefit. Over the course of the regular season, every team gains and allows extra homers (compared to past seasons) because of the ball, and the differences may mostly even out. Even if some teams do derive an advantage or suffer some penalty, it’s unlikely to affect the outcome of a pennant race that stretches over six months. And even if it did, we probably wouldn’t notice, because we can’t keep a mental tally of every team’s net gain or loss when thousands of homers are hit. In a wild-card game, a five-game series, or even a seven-game series, though, one well-timed homer is huge and hard not to notice.

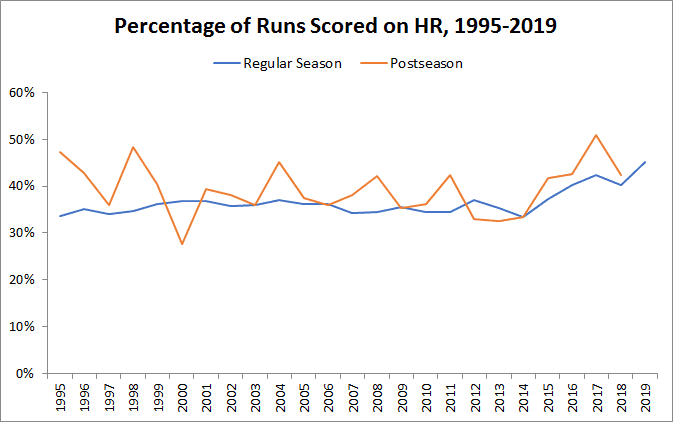

A feeble fly ball that snuck over the wall would be especially conspicuous in light of October’s stringent offensive environment. In the postseason, lower temperatures, better pitchers and fielders, and more aggressive bullpen management suppress scoring. The playoffs typically feature fewer runs than the regular season and a higher percentage of runs scored on homers, which makes it more likely that any given homer—no matter how weakly hit—will win a game and be burned into the disbelieving brains of the fans who went home unhappy.

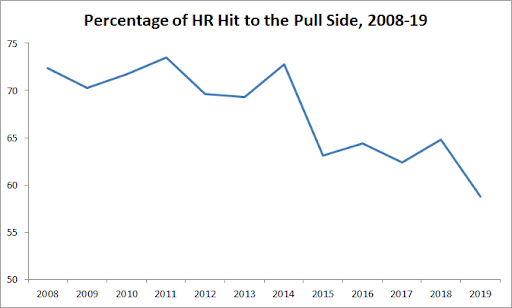

Pederson’s homer was somewhat extreme, but on the whole, home runs resemble his oppo drive more than they used to, at least in terms of direction. Although most balls in the air aren’t hit to the pull field, most home runs are. As recently as 2014, nearly three-quarters of homers were pulled. This year, that rate has dropped to 58.8 percent. Pulled fly balls are hit more than 4 mph harder and fly more than 30 feet farther than non-pulled fly balls, on average, but because the ball is carrying so much better than before, hitters no longer have to get all of it to clear the wall, and a higher proportion of flies are floating out to the opposite field or over the center-field fence. That’s thrown off players’ pattern recognition and forced fans to recalibrate how they feel about flies that wouldn’t have been no-doubters before the ball got so stubborn about staying in the air.

Here’s where left-handed hitters’ homers landed in 2014 vs. 2019, in GIF form. The biggest proportional increase has come on the left half of the field.

We got a taste of this looks like in big games in 2017, when Todd Frazier staked the Yankees to a 3-0 lead in Game 3 of the ALCS.

The lively ball helps hitters go deep on pulled pitches, too. In the 2017 World Series—which was plagued by complaints about baseballs with slick surfaces—Yasiel Puig and Carlos Correa launched off-balance and extremely steep two-run shots, respectively, for two of the seven homers hit in a back-and-forth Game 5.

“There are swings we expect to hit homers, and there are swings we don’t,” Jeff Sullivan wrote, scrutinizing Puig’s one-handed hack in a FanGraphs post that compared the two double-take-worthy dingers. “This doesn’t look like a home run swing, for whatever that’s worth. This doesn’t look like a home run follow-through. This looks like a desperation swat, and still Puig got his four bases. … This is precisely the sort of home run that makes people think the baseball is juiced.”

That trio of 2017 homers had help not just from the ball, but from Yankee Stadium’s shallow right-field fence and Minute Maid Park’s Crawford Boxes. Even so, as Sullivan wrote about Puig, “This has all the feel of a very 2017 home run.” This October, we’re going to see some very 2019 home runs, the kind we’ll shake our heads about when we watch them decades down the road, after the fusillade has subsided. If Manfred does deaden the ball before next year, fans of a team whose season ended partly because of the livelier ball would be entitled to feel fed up; sure, now he decides to do something.

It’s possible that the ball will spare the sport some controversy. Under current conditions, the would-be two-run homer hit by José Altuve in last year’s ALCS Game 4 that prompted a much-debated call might have sailed far enough out of Mookie Betts’s reach that Joe West would have twirled his finger instead of signaling fan interference. But that highlights only how important the ball can be. If Altuve’s drive had flown a few feet farther, the Astros, who lost that game by two runs, might have tied the ALCS at 2-2 instead of falling behind 3-1. Maybe they would have won that series. Maybe a dynasty would have been born.

Of course, some on-field factors are always in flux. Teams have won or lost postseason series based on blown calls that today would be quickly corrected by a replay review. Human umpires miss pitches that robot umps from the future would have classified differently. Players have recorded clutch hits with PEDs that weren’t yet banned or detected coursing through their systems. The Twins won two World Series with the Metrodome’s ventilation fans in their favor. The ball has been juiced before, though not to this extent. Plus, the playoffs are already random, capricious and almost impossible to predict, hinging on a bad hop here or a lucky bloop there, so what’s a little more madness?

October isn’t a time when the best team always wins, and baseball has never been played under consistent conditions. But we can still cast some side-eye at an anomaly that’s pulled focus from the players this year. Homers are worth four bases because they’re hard to hit. They’re the punishment for a pitcher’s mistake or the reward for a batter’s brilliance. Sometimes, now, they’re neither. They’re artifacts of a manufacturing quirk, scene-stealing interlopers like the water bottle in Westeros. So as October begins, brace yourself: Before the month is out, the misbehaving ball will probably put a permanent stamp on the playoffs.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference for research assistance.