As the Roy and Pierce families descend upon one another—the latter from their sprawling mansion, the former from their fleet of private helicopters—their collision course resembles the world’s highest-stakes game of Red Rover. On one side, the patrician custodians of a media empire whose sterling legacy stretches back generations; on the other, the blood-red arrivistes looking to buy their way into prestige and out of a takeover attempt. At first glance, their meeting looks like matter and anti-matter, an explosive mix of opposites that threatens to blow up in everyone’s face. Surely, one side must blink, or rather break, before the other. But if there’s one takeaway from “Tern Haven,” the stellar episode that brings the second season of Succession to its halfway point, it’s that far more unites these two wretched clans than sets them apart.

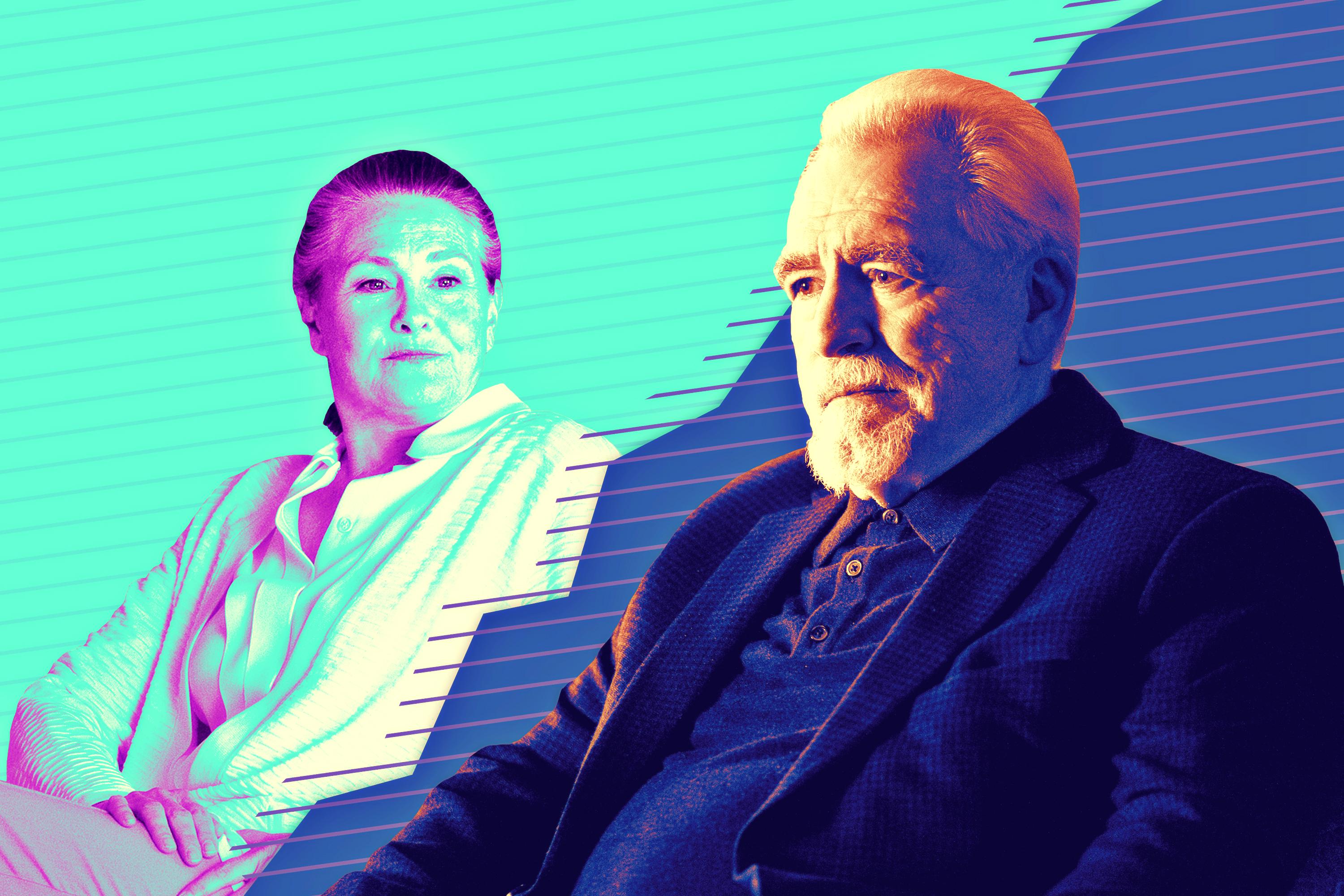

Ever since he successfully blackmailed his son into abandoning a would-be coup, Logan Roy (Brian Cox) has been fixated on a bold, possibly foolhardy strategy for warding off his attackers: swallowing another company whole and thereby becoming too big to acquire. But Succession has always been better at illustrating the personal manifestations of wealth than its big-picture machinations. Even as installments like last week’s “Safe Room” started to correct this imbalance by illustrating the gaping chasm between the Roys’ roster of telegenic race-baiters and the Pierces’ staid newscasters, “Tern Haven” returns to the show’s undisputed strength: a real-time vivisection of the rich, with the Pierces providing fresh meat to prove the scalpel’s still sharp.

The episode takes its name from the Pierces’ ancestral retreat, a sprawling New England compound they occupy with all the entitled ease of the Bushes in Maine or the Kennedys at Hyannis Port. (The real Tern Haven is located on Long Island, though production designer Stephen Carter cites the Kennedy compound as an inspiration.) Just as the Roys are an unholy blend of Murdoch, Trump, Redstone, and Kushner, so the Pierces splice together a few separate strains of American aristocracy. Like the Kennedys, the Pierces have an intergenerational claim on a genteel form of liberal politics. Like the Sulzbergers, they’ve kept their holdings in the family and shielded from the coarsening pressures of the marketplace, at least until now. And in her cardigans, pearls, and no-makeup makeup crested with a headband, patriarch Nan (Cherry Jones) bears a more-than-passing resemblance to Katharine Graham, the Washington Post owner recently memorialized by Meryl Streep.

A lesser show might take the same admiring attitude toward Nan that Spielberg expressed for Graham in The Post, the better to contrast her more responsible use of wealth with the Roys’ naked profiteering. Instead, “Tern Haven”—written by former Onion editor Will Tracy and directed by Game of Thrones alum Mark Mylod—crafts as savage a portrait of the Pierces in mere minutes as Succession has of the Roys in 15 episodes. The hour becomes a showcase for just how far Succession has come in a relatively short run; while certain members of the Roy family took the better part of a season to come into focus, “Tern Haven” outlines the Pierces’ black sheep and internal tensions in only a handful of scenes. It does so in the service of strengthening Succession’s core theme: unlimited riches corrupt without limits, no matter how dignified a face they present to the world.

In their bid to secure Nan’s seal of approval for the deal, the Roys are forced to make nice with their ideological mirrors. Incredibly, these out-of-touch monsters we’ve come to know and loathe become audience surrogates, serving as eyes and ears into a world as alien as the one that gave us Boar on the Floor. Nan airily quotes Robert Frost as she ushers the Roys onto the property; later, she demands a Shakespeare recital in lieu of grace, from a relative holding a ceremonial scepter. Guests are served “Hank Pierce’s brake bumper,” a cocktail recipe supposedly stolen from Teddy Roosevelt’s valet. The Pierce version of a failson cheerfully boasts of his second vanity PhD. The Roys are hardly strangers to the idiosyncrasies of their class, but in the moment, their poor poker faces reflect our disbelief. American discourse routinely frames WASPiness as the absence of culture, as the blank default against which other ethnicities are defined. “Tern Haven” shows the Pierces and their ilk to be as exotic as any far-flung tribe.

On Logan’s orders, the Pierces and Roys start to pair off, with each Roy assigned their own target to woo. Initially, these duos mostly offer comedic contrasts: Connor (Alan Ruck), the laughingstock presidential candidate bloviating at a bespectacled Brookings fellow; Roman (Kieran Culkin), unable to name a single book to his performatively literate interrogator. But the longer the two parties mingle, the more their quirks start to look like different symptoms of the same disease. Nan chiding her housekeeper for declining a drink—“You never treat yourself!”—or passing off her servants’ work as her own may be less harsh than Logan’s outright contempt for his employees, but their behavior comes from a shared condescension. Nan’s is just tempered by the delusion that her despotism is benevolent.

The most tragic connection is forged between Kendall (Jeremy Strong) and Naomi (Annabelle Dexter-Jones), both grown children trapped by their families and addictions. Naomi despises the Roys for their tabloids’ coverage of her mother’s death and her own car accident, but her attraction to a kindred spirit overpowers her repulsion from his last name. Both Naomi and Kendall are in recovery, maintaining private drug habits to fuel their public lives—Kendall as his father’s deputy, Naomi at a rehab facility in the Bay Area. Pausing in between lines to claim they have their habits under control, the two can’t help but laugh at how blatantly full of shit they are. But when Kendall posits the sale as an escape route, one trapped scion of privilege to another, Naomi chooses helping herself over screwing her enemies. “Just imagine getting out from under all this,” Kendall argues. “You could take the money and get the fuck out.” And so she does, leaving Kendall stranded in a pool of his own waste.

Money, as it turns out, is what bonds these apparent opposites together, and what punctures the Pierces’ pretensions to noblesse oblige. “You can’t put a value on what we do,” Nan protests in the meeting that serves as the trip’s true purpose. “I have put a value on what you do,” Logan replies. He’s right: This haggling is the point of the Tern Haven summit, not the elaborate dinners and moonlit stargazes; dollars are what ultimately matter to Nan and her brethren, not the journalistic cachet they take so much pride in. (Even the resident politico accepts Connor’s drunken offer of … the entire State Department.) And the Pierces don’t just take Logan’s deal. They go to him, after he leaves the bargaining table over the right not to name his young, qualified, charismatic daughter as his successor. Nan knows exactly who she’s handing her birthright to—“I’m not an idiot”—but she does it anyway.

Such hypocrisy engenders a different kind of disdain from viewers than the Roys’ more bald-faced greed. But the Pierces prove a vital plank in Succession’s anti-plutocratic platform, broadening its indictment of this country’s de facto ruling class. The show resists the temptation to make them foils to our antiheroes, a model of socially minded investment to the Roy’s self-interested hoarding. Their capitulation to Logan’s charm offensive is simply made all the worse by the ornate trappings that surround it, both literal and ethical. “Money wins,” Logan says as he toasts his own victory. It always does, even over those who already have it.

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.