The humidity hangs heavy in the air as I sit with Byron Leftwich under a tent at a recent Buccaneers practice. Tampa Bay summers like this can dry a man’s soul. Wear him down. But Leftwich is full of life and its lessons. “Color really shouldn’t come in mind. And you hope it don’t. Ultimately, you hope it never do.” Leftwich sounds sad as he explains this to me. He does not take his position lightly. He knows his career path is tenuous. “Football is a simple game, but nothing about it is easy, right?” he says. “When you break it down, it’s all hard. Everything is hard.”

Leftwich has accomplished something rare in professional football. He became the Arizona Cardinals quarterbacks coach two years ago—his first NFL coaching job—and after hurdling myriad challenges on a middling franchise, he ascended to offensive coordinator after Mike McCoy was fired last October. In January, Bruce Arians hired him for the same position in Tampa Bay. In many ways, Leftwich is following a familiar trajectory for a young assistant in the NFL. But he is a unicorn, one of two black offensive coordinators in 2019 (Kansas City’s Eric Bieniemy is the other). Leftwich chatted with Bieniemy about it at the NFL combine this year. He expects the two will exchange “good luck” messages before the season starts in a few weeks.

Leftwich tries not to put additional weight on his broad shoulders. He’s been black all his life. The same black boy from H.D Woodson High in Washington, D.C., who went on to become a star quarterback at Marshall, a first-round draft pick in 2003, and a Super Bowl champion in 2009, and now one of the few black coaches to hold an offensive coordinator role this decade.

“Don’t let nobody tell you that you don’t know [anything], because you know a lot just by playing. You play in this league seven years, you know a lot. You know a lot about football and don’t allow nobody to ever sway you on that,” Leftwich says. Overcoming the odds was no simple task. “It’s hard to get here. It’s hard to make it to this level. … Guys that make it to this level that played in this league, I want them to know, ‘Hey, man, you can coach this game.’”

It’s a crucial point for Leftwich. At one point, coaching was an afterthought after he finished his nine-year playing career in 2012.

“I finally talked him into it,” Arians tells me. “He wanted to play golf all the time! Shit. He had plenty of money, plenty of money. He wasn’t looking for a job.” Every year, Arians asked Leftwich, “‘Hey, you ready yet? You ready yet?’” Leftwich finally called in 2015 to tell his former coach he wanted to test the waters, and Arians brought him onto his Cardinals staff as an intern in May 2016.

As Leftwich speaks, I notice how proud he is of his second life in football. He lives for his players and the new Buccaneers gear he sports. He’s vital to the process of rejuvenating a moribund franchise—Tampa Bay has finished last in its division in seven of the past eight years—yet he’s an outlier in his profession. This season, 15 NFL teams will have a new offensive play-caller: Seven of those coaches are 40 years old or younger and, except for Leftwich, they are all white. Football’s most precious coaching commodities are overwhelmingly white men early in their NFL careers. The league’s power brokers are free to prioritize youth, and value innovation, in a coaching search. It becomes problematic if the talent pool that decision-makers are choosing from is mostly homogenous. The search for the next Sean McVay has yielded a group of coaches molded in his image. Matt LaFleur. Kevin Stefanski. Kellen Moore. Zac Taylor. Offensive geniuses, in this telling, more frequently resemble Kliff Kingsbury than Leftwich.

It still boils down to who is making that decision and what are they looking for. And our job is to make sure that there is somewhat of an open process, as much of a process we can have, that the viable candidates are considered.David Shaw, Stanford head coach

Teams are looking for offensive specialists to jump-start their franchises. It’s the current trend in a copycat league: The Cardinals hired Kingsbury as their head coach six weeks after Texas Tech fired him; Taylor got the Bengals job after serving as McVay’s quarterbacks coach with the Rams. But black coaches don’t feature prominently in discussions about offensive coaches. A Denver Post analysis in 2017 studied NFL hires from 2007 to 2017 and found that 110 of the 147 offensive coordinator positions filled during that time went to a former NFL and/or college quarterbacks coach. Of those 110 jobs, five went to black coaches. Three of those five went to the same coach: Hue Jackson.

The last NFL coaching cycle tells a troubling story about representation for coaches of color at the highest levels of the sport. Truthfully, every offseason does. There are systemic barriers that prevent black coaches from progressing in the industry. They know it. They see their white colleagues running teams as they labor for decades as assistants. We rush to anoint the McVays and Kingsburys of the world as the great new minds in football. But it appears no one is looking for the next black coaching wunderkind.

“We’re a powerful league. We’re capable of doing a lot of things, and I think we can fix this issue, but I don’t personally know how,” Leftwich tells me. He sighs. “Maybe one day I do have an answer on how to get this minority coaching situation figured out,” he says. But, “it’s not up to me to figure it out.”

“It’s not really about coaching, right?”

In November 2012, Jon Embree got emotional during a press conference to announce his firing as the University of Colorado’s football coach. Embree, a former tight end for the Buffaloes, inherited a disastrous team and won just four games in two seasons. He was the first black head coach in the program’s history, and one of 15 black head coaches in Division I at the time. “We don’t get second chances,” Embree said of black coaches. He later told the Denver Post: “You know we don’t get opportunities. At the end of the day, you get fired and that’s it, right, wrong or indifferent. … We get bad jobs and no time to fix it.”

Embree, now a tight ends coach with the San Francisco 49ers, was describing a problem black coaches in the NFL know all too well. The same year Colorado dismissed Embree, the league tapped Carlton Keith Harrison and Scott Bukstein, academics at the University of Central Florida, to study occupational mobility within the league. They published their findings in a report that addressed systemic barriers that coaches and personnel of color face, and provided data-driven policy recommendations to improve hiring conditions. The data is made public every year and is released without much fanfare or publicity by the league.

This year’s report echoes Embree’s sentiment from seven years ago. “Historically,” it reads, “NFL teams have been reluctant to hire a person of color for a head coach, offensive coordinator or defensive coordinator position after a person of color has previously served as a head coach in the NFL.”

The NFL has data tracking the occupational mobility of its coaches dating back to 1963. During that span, there have been 18 different black head coaches and four Latino head coaches in the league. In 2019, there are four head coaches of color, three of them black, compared to 28 white head coaches in a league in which more than 70 percent of the players are black. Since 1963, 112 white coaches have been hired as a head coach, offensive coordinator, or defensive coordinator after already having one head-coaching job, compared to 18 coaches of color in the same situation. For white coaches who have had two head-coaching jobs, 24 have been hired to these same roles in the future, compared to three coaches of color.

The most recent coaching cycle paints a bleak picture. Of 36 open positions at head coach, coordinator, or general manager, 30 of those hires were white candidates. According to the study, by February 2019, there were six fewer men of color serving as either an NFL head coach, defensive or offensive coordinator, or general manager than there were in February 2018. Data provided by the league office shows that, as of February of this year, NFL teams interviewed or sought to interview 61 total candidates for eight open head-coaching positions. Only 31 percent were coaches of color, and only seven of those candidates actually interviewed for those jobs.

The primary challenge for candidates of color, according to Harrison and Bukstein’s report, is breaking into the ever-elusive head-coaching pipeline. When teams keep hiring the same people to different roles, it creates what they described as a “reshuffling effect,” an outcome that reduces opportunities for new coaches, especially those of color. And lesser performances by white coaches are rewarded more than, or equal to, greater work by their black counterparts. This flattens how quickly talent of color can experience upward mobility.

“If you get fired and you’re a person of color,” says Harrison, the lead researcher, “the odds that you’re going to get reshuffled ever” are slim. At this point, he says, “it’s not even refutable.”

A 2016 Georgetown University research paper explained how leaders of organizations remain predominantly white despite efforts to increase racial representation in leadership positions. To anchor their assertions, researchers analyzed more than 1,200 NFL coaches at all levels from 1985 to 2012. They found that white assistant coaches were promoted at higher rates and made up over 70 percent of the hiring pool. There was “clear evidence of a racial disparity in promotion prospects for NFL assistant coaches that have persisted for over two decades despite a high-profile intervention designed to advance the candidacies of minority candidates,” the researchers wrote. They identified racial bias in lower-level coaching positions, such as receivers or defensive backs, and found that coaches of color are often hired into positions with inferior promotion prospects. Black and white coaches overseeing the same position don’t advance equally, either. Black coaches, the study found, are 114 percent less likely to become coordinators than their white counterparts.

“It still goes back to who’s doing the hiring and what they’re looking for,” says Stanford head coach David Shaw. “And unlike most professions, there is no ladder. Anything that looks like a ladder is false. It’s not a ladder. It has nothing to do with experience. … It still boils down to who is making that decision and what are they looking for. And our job is to make sure that there is somewhat of an open process, as much of a process we can have, that the viable candidates are considered.”

The obstacles presented are not easily overcome. Unless the structure changes, candidates of color will continue to be at a disadvantage in the hiring process. No hard work, no prodding, no representation at the highest level will change that. These factors create divergent outcomes for black and white coaches. Harrison and Bukstein’s study found that black coaches experience different rates of promotion than white coaches and are less likely to attain authoritative positions. Some of this, they argue, can be attributed to an unconscious bias in the hiring process on the part of white decision-makers, in which the résumés and skills of black coaches are devalued. Black coaches are also disadvantaged in a system where social connections serve as professional capital.

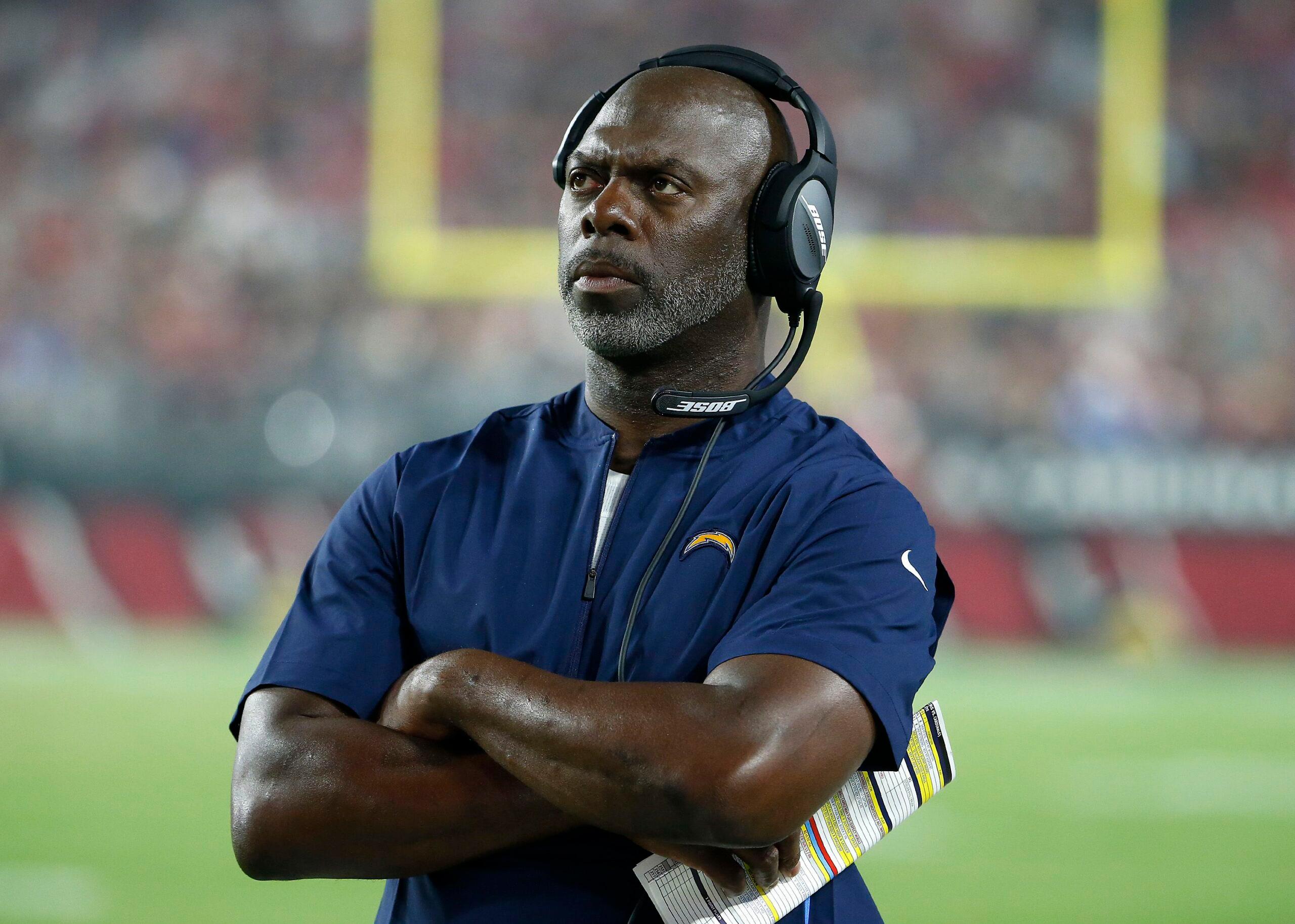

“I don’t think it’s ever been equal,” says Chargers head coach Anthony Lynn. “You know, the NFL is a great organization, but you can’t exempt the NFL from the rest of the world. How quickly are we moving up in the world? I don’t think it’s as fast as we would like.”

It makes the question Harrison poses in his study so important. “Would a coach of color be fired from a collegiate-level job and then hired by an NFL team as its new head coach?” Harrison asks. “There is no data to support this would occur.” People say Kingsbury “looks the part,” Harrison tells me. He’s not wrong. The white faces holding powerful positions at every level of the game have damagingly become football’s normalcy.

In June, the NFL hosted a quarterback coaching summit at Morehouse College, a historically black institution in Atlanta, bringing together the best black minds in the game. Troy Vincent, a former All-Pro and the league’s executive vice president of football operations, listened as black coaches from all levels of the sport shared their stories and offered their advice. In his closing remarks, Vincent responded with a passionate appeal.

“God damn it, we know this game,” he said. “We can coach it and we can teach it. All we’re asking for is a fair process.”

Vincent was involved in the league’s decision to commission Harrison and Bukstein’s annual study. “It’s important that we don’t hide,” Vincent tells me in July. He wanted the league to have a look in the mirror. The past seven years of evaluation have caused Vincent and the league to ask what they can control in the fickle process of hiring coaches. “As an organization,” he says, “what can we do?” The role of the league, he says, is to assist the clubs, be a resource, and identify and develop talent and then mentor coaches for the next phase of their career.

He recognizes what he describes as the “trend” of looking for offensive-minded coaches. He touted the quarterback summit as a way of bringing in a bevy of black play-callers and praised the fellowships and internships that coaches of color frequently receive to work inside franchises. But Vincent didn’t have an answer for why these efforts haven’t produced better results.

“We’re just trying to control what we can control,” Vincent says. “And that is to continue to prepare those individuals that have been identified, to get them ready so that when that opportunity arises, we hope that decision-maker is looking across the board,” and picks a black coach. “No one likes the results,” he admits. “But the results are the results.”

Don’t tell me I have to check the box to be a coordinator before I can be a head coach, and then two years later you hire young guys that never called a play a day in their life.Anthony Lynn, Chargers head coach

Vincent consistently told me that the NFL wants to be a model for diversity initiatives, that diversity is good for business, and that the NFL is like any other American organization. “We can probably talk about the organization you work for and all others,” Vincent says. “We see the disparity all across America. It’s been that way for a long time.”

Vincent says the league doesn’t believe the Rooney rule needs to be altered, though numerous black coaches I’ve spoken with say it’s often used as a box-check for organizations who aren’t serious about hiring a coach of color.

I ask Vincent whether the league can do more to push teams to be better on the issue. He says the league is doing all it can. “We cannot require the club or make the club hire. You’re going to hire who you think is best suited to run your organization.”

The league supports these coaches and hypes them at motivational summits, but is hesitant to lead on the issue. It’s content to let individual franchises conduct their own hiring processes. If there were corrective measures, or consequences, football’s hiring powers would be pushed to do more than they have. As is, the shield is safeguarding their most profitable stakeholders, ensuring that progress is a foregone reality.

“The system is sick,” Rod Graves tells me over dinner in Washington, D.C., one night in July. Graves, a longtime front-office executive, is the new face of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, an advocacy group formed in 2003 that works to improve hiring practices for coaches and executives of color in the NFL. It’s Graves’s job to be a voice for change. It’s not like he’s unfamiliar with the game. The 60-year-old from Houston worked in the NFL for three decades, including a 15-year career with the Cardinals, where he served as vice president of football operations (1997-2001) as well as general manager (2002-12). Under the dim restaurant lights, Graves appears visibly troubled. How can he succeed where others before him have failed?

“The thing that I tend to get a little bit emotional about when it comes to the focus of the league now is the idea that we need to be focused on the pipeline,” he says. Black and brown talent has always existed, he says, and the league acts as if there hasn’t been a crop of diverse coaching talent whiling away on teams each season.

“We have not given enough attention to those who have given their lives to becoming professionals, who are really good and ready today,” he says. “We ignore that group as if they don’t really exist. There are well over 100 coaches of color in the league, and yet we don’t talk enough about those who are in the same category [Chargers coach] Anthony Lynn was in several years ago. … Guys deserve an opportunity. And yet, they’ve not been called for one interview.”

Graves will make an impact if he can change the messaging around hiring practices for coaches of color. He agrees with Vincent that diversity is good business.

“It’s positive for our fans,” Graves tells me. “When people look at who the leaders are and the opinions expressed out of an organization, they tend to feel there’s opportunities in the National Football League for all of us. The game is not just for a privileged few. Those things suggest the game is available to everyone. And it should be.”

Graves spent 30 years working alongside the league’s decision-makers, including its billionaire owners. He believes quantifying the economic benefits of diversity, and communicating it effectively to the league’s power brokers, will be powerful tools for the Fritz Pollard Alliance. The owners speak in dollars and cents, and that is one way Graves intends to articulate his message.

“What we have to do is somehow have more conversations about how diversity affects the bottom line,” he says. But even he understands this is a long shot. “We may not necessarily change opinions. But owners certainly are concerned about money. If we can show that diversity is more profitable for their business, we’ll get more diversity-related approaches in business plans of owners.”

Within their advocacy, leaders like Graves need to grapple with the reasons these coaches are hobbled in their profession. Steve Wilks and Vance Joseph were both fired last year, the former after one season with the Cardinals and the latter after two seasons with the Broncos. Both will be defensive coordinators in 2019. It’s as Jon Embree preached seven years ago: Even with the right people in power, candidates of color have difficulty getting second chances. They are given short strings and asked to knit full sweaters.

Graves promises me he sees this. He had to fight for his opportunities in NFL front offices, and hopes to use the rest of his life to change a broken system. He’s willing to wrestle with the obvious.

“Most are hesitant to say, but the standards are different,” Graves says. “For whatever reasons why people decide to go in a certain direction, I’m not questioning the legitimacy of those reasons, but what I am questioning is why don’t people of color get the same opportunities in the same situations?” He sits for a second with his thoughts. “You have to certainly consider racism,” he admits. “You have to put it in the context of a bias. There is a bias and that bias is working against these coaches.”

Anthony Lynn tells me two stories this summer. As a rookie running back for the Broncos in 1992, Lynn and his teammates developed a ritual on game days. To kill time while they were sitting in the locker room before games, they flipped through team media guides, looking for something specific: How many black faces coached on the Giants? Or the Lions? Or anywhere? “You’d just flip through the pages, and I just remember we would be well aware of how many African Americans were on staff,” Lynn tells me.

“Hey! I want to play here one day,” players yelled across the locker room. “You know this company right here is really diverse.”

Lynn said he wouldn’t be surprised if current players had a similar ritual. “You’re well aware of which organizations have the most diversity. It’s just something that interests minority players,” he says. The second tale Lynn tells me is just as important.

When Lynn was a child, his grandfather would speak to him before football practices. One day, Lynn said he told him: “To go where you want to go, you’re going to have to run faster.”

“Grandpa,” a precocious Lynn shot back. “What are you talking about? I’m the fastest kid on the team!”

“One day,” his grandfather said. “You’re going to understand what I’m talking about.”

“Well,” Lynn tells me now, “it took a while, but I understand exactly what he was talking about now. That’s just the way I was raised. I knew the rules of the game, and I knew that it wasn’t always going to be fair and I knew that I was going to be better, that I was going to have to try harder.”

Lynn says his grandfather’s advice prepared him for life and for his future in the NFL. “Nothing really surprised me,” he says. He notices when the goalposts move for black and brown coaches. He thinks the criteria changed this year as teams looked for the next offensive mastermind, even if those coaches have limited NFL experience, or any at all.

“When I went through the process, that pissed me off,” Lynn says. “I was told by an owner that he wanted to hire me and the reason why he didn’t hire me was because I hadn’t been a coordinator and the other guy had. And I said, ‘Don’t take this the wrong way, but I think that’s fucked up.’”

“Don’t tell me I have to check the box to be a coordinator before I can be a head coach, and then two years later you hire young guys that never called a play a day in their life,” he continues.

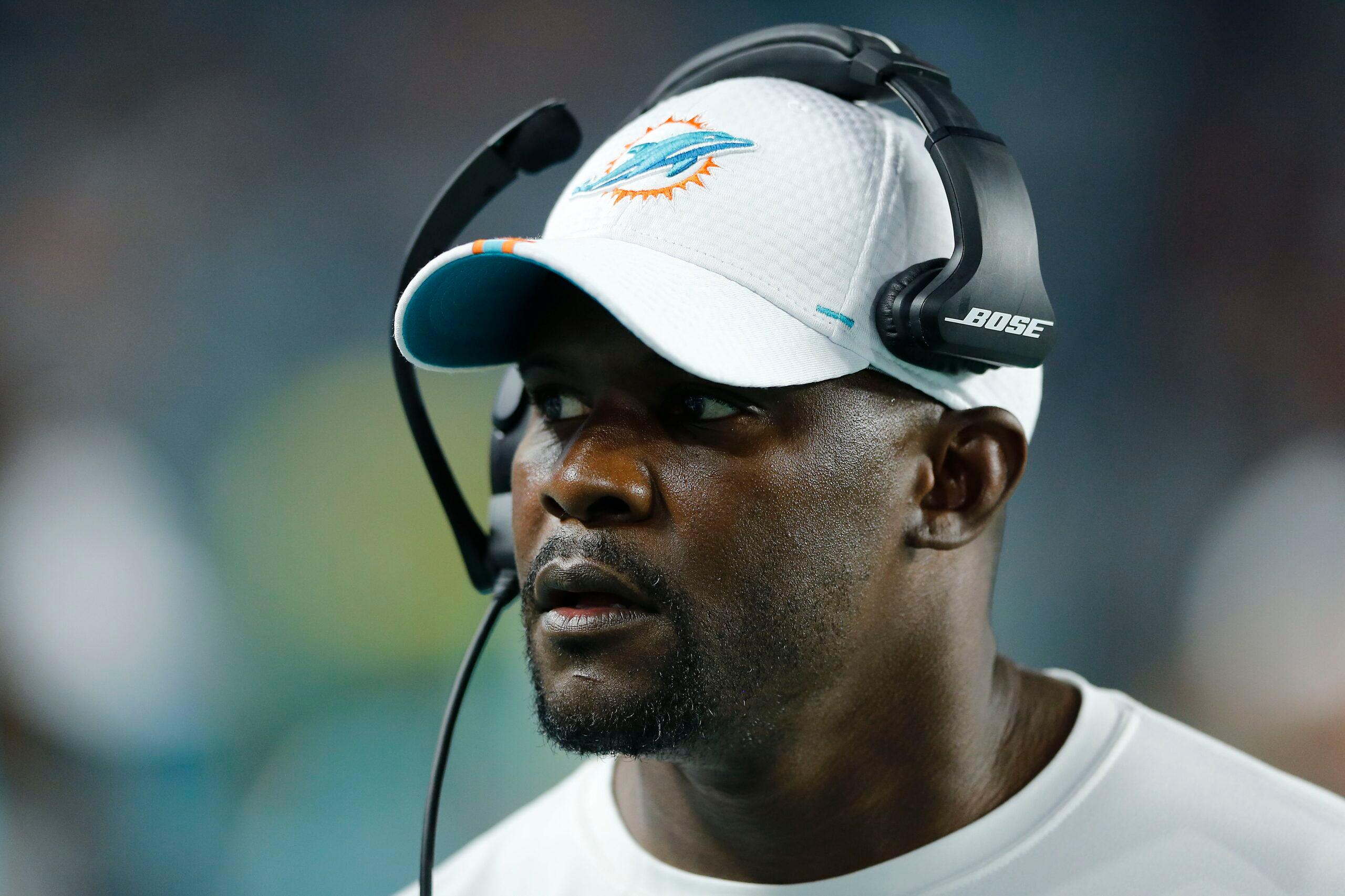

There’s a lot of really good coaches in this league. You gotta do more investigation. Dig deeper. Turn over every stone. If you look hard enough, you’ll find them.Brian Flores, Dolphins head coach

Lynn’s frustration was a common theme with many of the coaches I spoke to. The criteria change, and they are passed over for younger white coaches. They have to wait longer to ascend in their profession if they ever get the call at all. After Rex Ryan was fired by the Jets in 2014, Lynn was asked to interview for the head-coaching vacancy. He said he nearly declined because he said he knew it was a Rooney rule interview. “I was like, you gotta be out of your damn mind!” He changed his mind after his friends called him and told him to take the interview. He didn’t get the Jets job but was hired as the Chargers’ head coach a few seasons later.

It doesn’t work out that way for many coaches, however. Lynn spent 17 years on the sideline before his number was called. Being on the opposite end can be just as draining. Raheem Morris was a young, upstart coach when he got his first head-coaching gig in 2009, at 32 years old, with the Buccaneers. He was fired after three seasons. The NFL’s mobility data suggests it’s unlikely he’ll get the head-coaching hat again.

“I know it’s frustrating,” says Morris, the Falcons’ assistant head coach and offensive passing game coordinator. He tries not to spend too much time wondering whether he got a fair shake in Tampa Bay. “I’m 42 now. It’s been 10 years, and I think my time will come again. I want to be one of the few guys that you’re talking about that got the second opportunity.”

Morris tells me it’s important not to get stagnant, or to make excuses, to only move forward. I ask him whether doing that can overcome the inherent biases keeping him and others out of head-coaching offices, or combat a hiring process that selects from a pool of mostly white coaches for head jobs.

“I have no choice but to believe that,” he says.

This rejection is one of the reasons Shaw remains in his college football castle at Stanford. Shaw is often brought up as a candidate to make the leap from college to the NFL. He doesn’t see why he should. He remembers being bounced from the NFL in 2005 when he was a Ravens assistant, and doesn’t wish to revisit that experience.

“If you coach longer than three years, then you know rejection,” Shaw tells me. “I’ll say it nicely. When I left Baltimore or was asked to leave the Baltimore Ravens, I interviewed for multiple jobs and tried to get multiple jobs and struck out multiple times. And multiple times I thought I had the job. I thought I was the perfect person for the job and crushed the interview, and someone else got the job.” Those denied opportunities eventually brought Shaw to his alma mater, but he never forgot those feelings of disappointment.

“If people have closed minds, hey, it’s up to us to try to open those minds the best way we can and continue to have great examples of people that don’t look like the cardboard cutout football coach,” Shaw says.

The challenge for these coaches is compounded when they can’t break in immediately. Keith Armstrong has been coaching special teams for 27 years and is currently the Buccaneers’ coordinator. For years he gave up his summers to participate in the Minority Coaching Fellowship, a diversity workshop the league recommends for upstart play-callers. “I never went on vacation for four years,” he says. “Sometimes, you gotta give that up.” But what if he hadn’t been a young 20-something without a relationship or kids? He may have never made it in pro football.

“You gotta be willing to grind,” he says. “And a lot of guys have. But you have to have a lot of luck. I been lucky as hell. I got horseshoes. I can’t say that for the rest of ’em.” Armstrong admits a lot of his fortune came from other coaches’ social capital. Jimmy Johnson made calls on his behalf in the ’90s. Arians has done the same. “A lot of this stuff is who you know, who you gather with. Everybody travels in families and packs, and you gotta get caught up in one of those families,” Armstrong says. But he knows his tenure in the league is nowhere near the norm.

“It can be frustrating. There’s no doubt about it. It’s just like the real world,” he says. “You gotta keep gettin’ up. That’s the thing here. Because you’re gonna get knocked down. Keep gettin’ up.”

Even with all the anecdotal evidence and quantitative conclusions about the state of coaches of color in professional football, these results don’t sit the same with everyone. Black people are not a monolith. Every black coach is not forced to find fault with the state of their profession. Dolphins head coach Brian Flores told me last week that hard work would prevail.

“I just, I just,” Flores sighed. “Speaking truthfully, honestly, I feel like guys who work hard and do a good job are productive. They can lead, they’ll get their opportunities. Maybe that’s a pipe dream of mine.”

During his introductory press conference in February, Flores said he wanted to be an example for coaches of color to help them get the same opportunities. He takes it seriously, he said. He’s seen the richness of talent in the game. He was brought up for years as a coach who was next in line. Now, he’s reached the top. And he wants to see something change.

“This isn’t an offense or a defense or special teams job. This is a leadership job,” he says. He wants those with hiring power to work harder. “People need to, I don’t want to say broaden their horizons, but take a good, hard look, investigate a little bit more, take the time to listen to players and listen to other coaches. There’s a lot of really good coaches in this league. You gotta do more investigation. Dig deeper. Turn over every stone. If you look hard enough, you’ll find them.”

No one person can be a shining light to influence those who are unwilling to see that black coaches are capable of the same things that their white counterparts are.

If the trailblazer Tony Dungy, the first black coach to win a Super Bowl, could not convince them, or Mike Tomlin, with the third-longest tenure among active coaches, or Jim Caldwell, Dennis Green, Fritz Pollard—if they could not change the minds of football’s power brokers, then who can? The NFL is not unlike many American workplaces. The culture of many of this country’s elite institutions, football included, is built on race-based exclusion.

It is not the job of any black coach to attempt to fix the structures in their workplaces. It is a deeply unfair expectation for a group of people who’ve been refused a seat at the table since the legs were screwed on and the silverware set. It is not a question of whether black and brown coaches can succeed at the highest levels of the game—it’s a matter of when we will let them.

Many consider Leftwich to be the next man who will reach glory. “I’ve been around some really good African American coaches on both sides of the ball. Like really, really, really, really good coaches,” Leftwich tells me. He’s a product of what this collective of coaches has always wanted: representation, yes, but also advancement based on merit. “We are in the teaching business,” he says. “And the teaching business can no longer be about color.”

Getting the job in the first place is only one step. “When it takes this long to get one, and if you do get an opportunity and you’re not ready, you’re done. You never get another chance again,” Lynn says. “That’s just the way it is. I can’t say that’s the same for everybody, but it’s damn sure the same for us.”

Lynn rests for a minute and tells me one last story.

“I hope that the data is wrong,” he reveals. “I still look forward to the day that every man gets his equal opportunity.”

“I hope one day it’s wrong, too,” I admit.

Lynn laughs and says, “I know you do.”

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that Lynn interviewed for the Bills job.