The end of the world never feels like the end of the world. The human brain simply isn’t built to grasp the stakes or scale of existential threats, which it can’t help but process on the same continuum as the more mundane struggles of one’s everyday life. Nor does the relentless march of time pay much mind to the relative significance of certain events. Every disaster has a day after; every cataclysm is afforded the chance to fade into collective memory, so long as there are still people around to remember.

But if the apocalypse doesn’t feel like the apocalypse, what does it feel like? That’s the central concern of Years and Years, the British series currently four episodes into its six-episode stateside run on HBO. (The hourlong show initially aired from mid-May to mid-June on BBC One.) Created and written by Russell T. Davies, of the original Queer as Folk and superlative Cucumber/Banana, Years and Years combines the grand sweep of a near-future dystopia with the warm intimacy of a family drama. Its protagonists are the members of the Lyons clan, a racially, ideologically, and temperamentally diverse group headquartered in Manchester, England. Its setting is the next decade or so of global unrest, which, in Davies’s anxious imagination, only continues to escalate from its current seeming fever pitch.

“We used to think politics was boring. Those were the days,” sighs Daniel (Russell Tovey), a housing officer who will soon find himself in love with a Ukrainian refugee. “Now, I worry about everything. I don’t know what to worry about first. I don’t even know what’s true anymore. What sort of world are we in? ’Cause if it’s this bad now,” he says, turning to his newborn nephew, “what’s it gonna be like for you?”

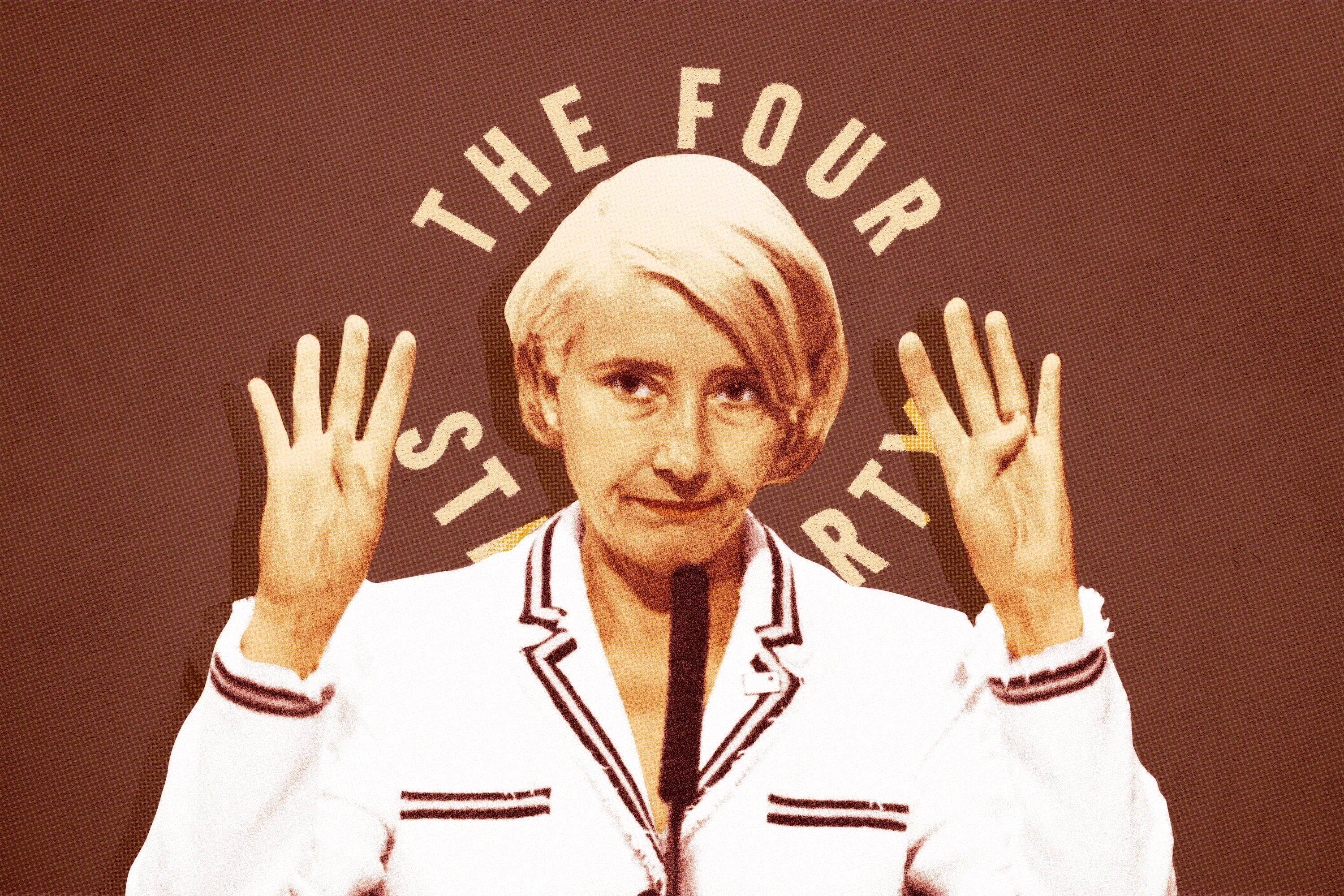

Years and Years is Davies’s attempt to answer that question, now urgent for millions of millennials debating whether to have children in the face of climate change, or place their faith in rapidly deteriorating democracies, or square the daily onslaught of headlines with the stubborn inertia of their daily routines. Davies juxtaposes the everyday struggles of the Lyonses—the aftermath of their mother’s death and their parents’ messy divorce; the simmering tensions between the matriarch and her daughter-in-law; the usual sibling rivalries and grievances—with the geopolitical turmoil around them. Sometimes, the two overlap directly: A globe-trotting activist sister witnesses an American nuclear strike firsthand, while Daniel’s love life puts him right in the center of the international migration crisis. Other developments linger more menacingly in the background. Rosie (Ruth Madeley), a working-class single mother, falls gradually under the spell of politician Vivienne Rook (Emma Thompson), an iconoclastic outsider in the Trumpian vein. (Rook is a great deal more convivial, and a great deal more frightening, than the other besuited authority figure Thompson plays this summer.)

From a financial crisis to yet another liberal bastion succumbing to its right wing, many of Years and Years’ plot points are terrifyingly plausible. Yet Davies is less interested in predicting the events of the future than capturing the mood of our present—the continuation of ordinary lives under extraordinary circumstances. In this respect, Years and Years joins a growing subgenre of television that brings post-Trump, post-Brexit entertainment into its second phase. Now multiple years through the looking glass, some creators have moved past urgent, topical responses and into a more abstract phase of processing their emotions into art. With the facts of our shared situation now well established, television has moved on to depicting its feeling.

Immediately following the 2016 election, many television shows seized on their medium’s compressed production timeline to channel their angst. Sitcoms including The Carmichael Show, Black-ish, and even the embattled, short-lived Roseanne revival dedicated episodes to families hashing out their emotions; Ryan Murphy devoted an entire season of American Horror Story to post-election agita. The specificity of these works was both their appeal and their chief limitation. In striking while the iron was hot, they tied themselves to a particular time and place at the expense of long-term relevance. Now, like the 9/11 installments of shows like The West Wing, their long-term utility is as a time capsule, not narratives in their own right.

Then, in 2018, erstwhile web series High Maintenance kicked off its second season on HBO with “Globo,” an episode offering a different kind of catharsis. Following the adventures of an anonymous, Brooklyn-based weed dealer known only as “The Guy” (Ben Sinclair), High Maintenance uses its framing device to explore the many facets of the New York experience, starting with The Guy’s fellow white hipsters and radiating outward. Most High Maintenance episodes juxtapose a handful of unrelated stories, connected only by The Guy’s presence as businessman or bystander. “Globo,” on the other hand, unites all three of its component parts under the umbrella of a very particular kind of New York experience: the collective response to a historic disaster.

The event in question, which causes demand for The Guy’s services to skyrocket, is never named. It’s definitely not the 2016 election, at least in a literal sense; early on, The Guy references the infamous Oscars mix-up that didn’t happen until spring 2017. But by never specifying the source of their characters’ angst, Sinclair and his cocreator Katja Blichfeld allow viewers to project any number of anxiety drivers onto the show. The genius of this vacuum is that the cast could be reacting to any number of modern calamities: yet another horrific mass shooting; a natural disaster worsened by climate change; the latest democracy to slide toward totalitarianism. What matters isn’t the specific cause, but the cumulative effect.

New York is a city of millions of people leading independent lives. An event of this magnitude suddenly and violently reroutes those lives onto the same track—an experience equal parts soothing and haunting, familiar to anyone who passed the spontaneous wall of Post-its put up in a subway station in the fall of 2016. But just like the Lyonses in Years and Years, the High Maintenance crew can’t help but continue as they were, even as history happens around them. The Guy makes his rounds; a yuppie tries to maintain and celebrate his weight loss; a parent cares for their child. By broadening its focus from Trump alone, High Maintenance allowed itself to explore a more universal truth about living through interesting times, a mantle taken up by more series since.

The Good Fight manages to have it both ways. Robert and Michelle King’s CBS All Access legal drama is very much about American politics at this particular moment, using the casework of a Chicago law firm and embattled partner Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski) to dramatize hot-topic issues like impeachment and ICE raids. But even if the content of The Good Fight can be ripped from the headlines, its tone works to capture a more general sense of disorientation, blurring the line between real and surreal, horror and comedy.

The Kings spent years exploring the link between high-level politics and everyday casework on The Good Wife, preparing them to do the same for a very different regime on The Good Fight; rare is the procedural that makes a point of which administration the presiding judge was appointed by. Yet The Good Fight also makes a point of following its litigators home at the end of the day, addressing not just their work but their disposition, which can’t help but be affected by the chaos around them. In Season 2, Diane started microdosing psilocybin to cope with her diminishing sense of control; in Season 3, she and colleague Liz Reddick-Lawrence (Audra McDonald) joined a vigilante resistance group working to fight Trump by any means necessary, including fatal SWATtings and attempted election fraud.

Sometimes, The Good Fight seems to almost tempt fate with its heightened reality, sprinting right up to the edge of either poking the hornet’s nest or bursting its fragile bubble of suspended disbelief. A Season 3 plot about a potential Melania impersonator asking for advice on a potential divorce was breathtaking in its audacity; an animated short about Chinese censorship ran afoul of CBS’s actual Chinese business interests. But such daring is crucial to The Good Fight’s ability to channel the spirit of our current moment by violating its letter, distorting reality just enough to capture just how distorted it truly is.

Like Years and Years and High Maintenance, The Good Fight belongs to a school of storytelling that digs past the news in order to explore the news’s psychological effect. These shows understand that the personal and the political are hopelessly enmeshed in one another, and the average person simply isn’t equipped to untangle or properly prioritize the two. TV works by forging connections between audiences and characters they get to know over time; these TV shows in particular use that connection to give impossibly vast problems a flawed, human face. The end of the world doesn’t feel like the end of the world, but those affected by it look just like you and me.