When All Elite Wrestling executive vice president Cody Rhodes took a sledgehammer to a throne topped with WWE chief operating officer Triple H’s symbol at AEW’s inaugural Double or Nothing event, he threw down the gauntlet. The match that followed, with his brother Dustin, was an old-school delight, saturated with blood and emotion, but the destruction of the throne pointed to the future—another war between wrestling promotions was underway.

And even if AEW, boasting a television contract and financial backing seemingly sufficient to support its ambitions, isn’t yet a serious competitor to a billion-dollar, multinational corporation like WWE, it might serve an even more valuable purpose: a fillip to enable the sport as a whole to reach new artistic heights. And the WWE has seemingly responded in kind, upping the ante by elevating Attitude Era masterminds Paul Heyman and Eric Bischoff to major creative roles in advance of the company’s Extreme Rules pay-per-view this weekend. (One might even see it as WWE getting on its war footing by elevating the two losing generals of the last major era of promotional competition.) Those moves shouldn’t come as a surprise, since through the long history of promotional wars, stretching from the Attitude Era brawl between Ted Turner’s WCW and Vince McMahon’s WWE all the way back to the shady origins of professional wrestling in the late 19th century, competition has always disrupted complacency and fostered creativity.

Simply put, when promoters go to war, the fans usually win regardless of which magnate ends up drawing the shorter end of the money straw. This is a helpful reminder that at a time when promotional tensions might be riding high, we should sit back and enjoy all the shows instead of casting our lot with one brand or another. The AEW product, which involves a lot of agile cruiserweight-size wrestlers and very few traditional heavyweights, offers a distinct contrast to a WWE that has the massively muscled Bobby Lashley feuding with “The Monster Among Men” Braun Strowman. Cody Rhodes understands this, too, telling Variety that “competition raises everybody’s game.” For Rhodes, being “competitive means being profitable,” not that “we have to have this to beat the WWE.” When battle lines are drawn and big bucks are at stake, Eric Bischoff got it exactly right: controversy creates plenty of additional cash.

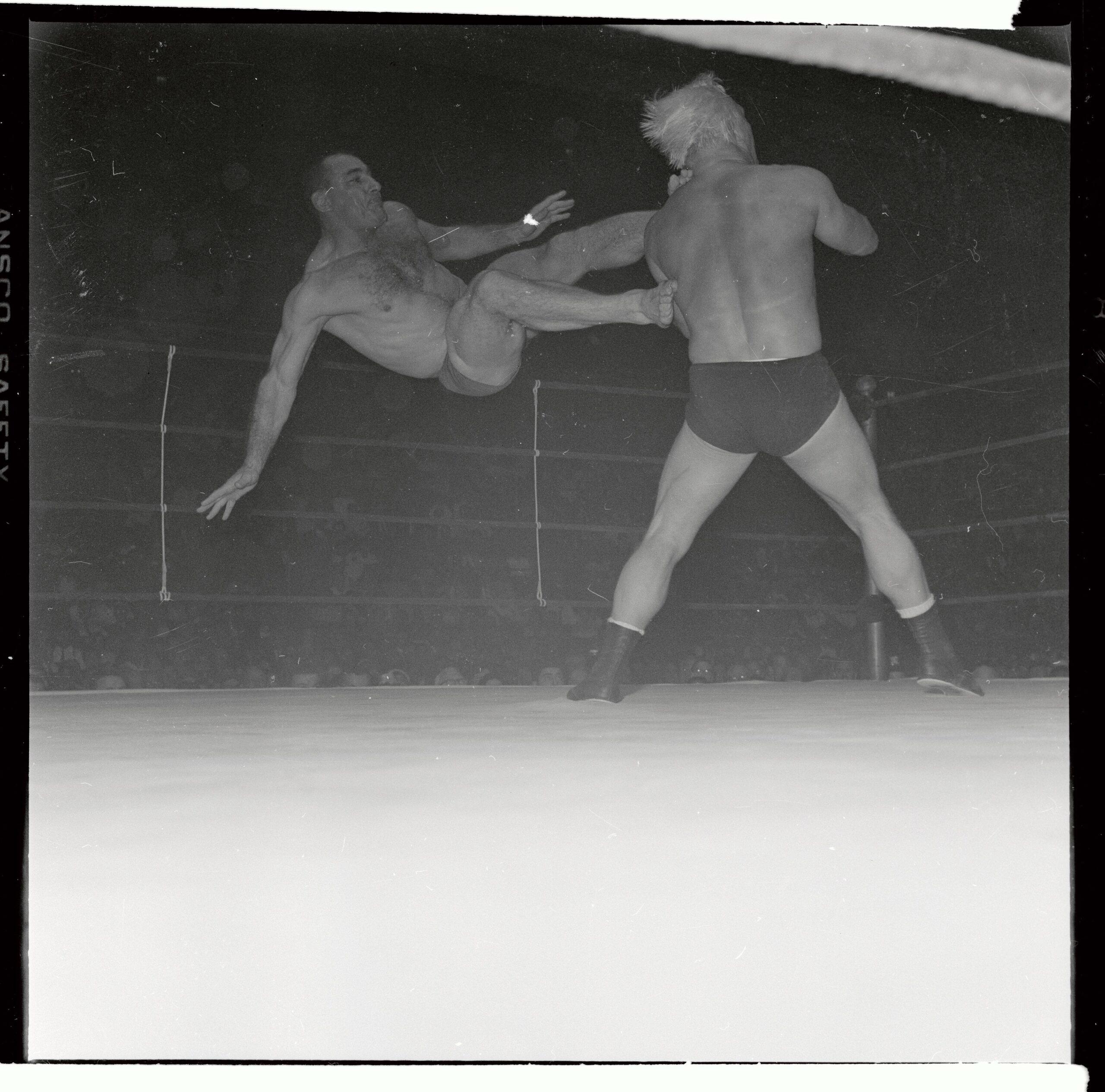

And those controversies, and their resulting struggles and eventual payoffs, have accompanied the sport from the beginning. When carnival-trained grappler Frank Gotch battled massively muscled European star George Hackenschmidt in 1908, a greased-up, slippery Gotch frustrated his rival, scoring big with roughhouse tactics like head-butting and biting before securing the win with a toehold submission. Hackenschmidt pitched a fit, claiming unsportsmanlike—and perhaps even illegal—tactics, and all that did was further inflame opinions throughout the wrestling world prior to their rematch three years later. The second match was a dud—Hackenschmidt entered the duel with an injured knee, and Gotch secured a win so easily that many suspected the outcome was fixed (or, alternately, that Gotch had paid “hooker” Ad Santel to inflict that knee injury on Hackenschmidt). But the buildup to the second payoff match between these two reigning powers in the sport still lined both their wallets.

A need for exciting finishes as opposed to two-hour, anticlimactic “lay and pray” amateur bouts with little action, prompted a shift toward predetermined outcomes in the early 1920s. And when that power shifted into the hands of the men who paid to stage the bouts, the stage was set for all kinds of skulduggery and double-dealing in the interest of personal profit. Attempts to consolidate control through the use of capable “hookers” like Ed “Strangler” Lewis and Joseph “Toots” Mondt, the two skilled enforcers at the heart of promoter Billy Sandow’s “Gold Dust Trio” that controlled much of the wrestling business during that decade, were always imperiled by the possibility of genuine in-ring competition: an opponent going rogue. And when veteran wrestler Stanislaus Zbyszko cut a deal with rival promoter Jack Curley to legitimately defeat the Gold Dust Trio’s popular champion Wayne Munn, a former college football great but a wrestling novice, he scored an easy pinfall victory and then quickly dropped the title to Joe Stecher, another veteran wrestler who was the star of Curley’s opposition outfit.

Stecher held that strap for three years, before cutting a deal to lose the belt back to Strangler Lewis—they buried the hatchet for a quick payday, which would prove to be a recurring theme of these bruising battles. The Gold Dust Trio would split apart not long thereafter, with Strangler Lewis gradually losing both his ring conditioning as well as his vision, Toots Mondt relocating to New York to team up with erstwhile foe Jack Curley and throw his promotional weight behind handsome young grappler Jim Londos, and Billy Sandow tying his creative fortunes to capable amateur stars like 1936 Olympian Roy Dunn.

Mondt, as was the case in a business characterized by ever-shifting allegiances, soon found himself running New York alongside Curley and the up-and-coming Jack Pfefer, a preternaturally creative Jewish immigrant who rose to prominence in the 1920s by booking shows featuring a series of “Eastern European menaces” who would challenge American wrestlers. Pfefer, would later split from Mondt alongside top attraction Jim Londos, and after their business fortunes tanked he pulled the ultimate heel move: He exposed the business, telling the New York Daily Mirror that match outcomes were predetermined. When it came to competition, Pfefer, who always fought dirty, wasn’t afraid to throw the entire sport under the bus to put himself over.

And while these revelations hurt business in the short term, it didn’t matter in the long term because Mondt did whatever any solid promoter does in the face of competition: He studied the market and regrouped, rebuilding the New York wrestling scene around relatable ethnic champions. And Pfefer, an inveterate huckster who didn’t mind booking entire cards featuring lookalike wrestlers with stage names that sounded like the names of actual top attractions, soon reconciled with Mondt when it became clear this reunion could help line his pockets. Mondt, in turn, had gained more or less monopoly control of the large New York market after Jack Curley’s death, and partnered with longtime New York matchmaker and fight promoter Jess McMahon and Jess’s son Vincent to form the Capitol Wrestling Corporation in 1952, a well-funded outfit built to withstand competition throughout New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland.

Wrestling became extremely lucrative in the early days of television, when ring-based sports like boxing worked well with primitive single-camera setups, and so promotional wars intensified. Markets like Chicago, run by Fred Kohler and broadcast nationwide on the DuMont Television Network, had long stretches beginning in the late 1940s in which promoters could essentially print money, but Kohler and other territorial promoters were themselves constantly at risk of “invasions” from rivals. Even if these promoters controlled the airwaves, their rivals could run opposition shows in their markets, possibly cutting into box office revenues. And a city that was booming, like Chicago, was always a prime target for such incursions—where better to promote your own shows than an area already made receptive to pro wrestling through the work of another promoter?

The solution to all this competition came in the form of an umbrella organization of regional promoters, the National Wrestling Alliance. The United States and Canada were still quite fragmented in terms of transportation and communication, and dozens of promoters could comfortably coexist under the NWA banner. This, in turn, afforded them a kind of decentralized monopoly that provided fans across the country with a single recognized world champion, usually a top-flight grappler like Lou Thesz whose mat skills would prevent any kind of funny business if an opponent went off script, and would quickly supply star wrestlers if unsanctioned promoters tried to cut in on their business. Comity was certainly the vision of the organization’s longtime head, ever-diplomatic St. Louis promoter Sam Muchnick, but the reality was far different: Even within the NWA, promoters were constantly battling over cities and either threatening to leave or leaving the alliance, like amateur star and American Wrestling Association founder Verne Gagne did after he was refused a run with the NWA title in the 1950s or World Wide Wrestling Federation promoter Vincent J. McMahon after he refused to recognize Buddy Rogers’s loss of the belt to Lou Thesz in 1963. (McMahon returned to the NWA fold in 1971.)

Then in 1956, at the peak of the organization’s effectiveness, it was saddled with a consent decree from the federal Department of Justice for its efforts to restrict trade within the wrestling business. The NWA didn’t have to pony up cash to pay a penalty, but it was forced to operate a bit more subtly, and its various promoters continued to bicker over everything—who would hold the NWA championship, where the champion would be booked, and who would inherit specific territories and cities within these territories if a designated promoter died or retired. These were creative people running what were by and large shoestring operations with extremely tight profit margins, and the resulting creative tensions meant future competition was unavoidable.

Even operating within the borders of the NWA, unsanctioned “outlaw” federations abounded. After Atlanta promoter Ray Gunkel died from a heart attack following a match with Ox Baker in 1972, his minority partners, Paul Jones and Lester Welch, chose to close Gunkel’s promotion and share their territorial rights with a new ownership group led by “Cowboy” Bill Watts. Ray’s widow Ann and several renegade wrestlers, Thunderbolt Patterson and “Big” Jim Wilson notable among them, ran opposition to incoming NWA-backed promoters Watts and his replacement Jim Barnett. After taking the reins from Watts in 1974, Barnett—a well-connected socialite and mat impressario who had run profitable operations in Detroit, Indianapolis, and Australia—used his many political connections to shut Ann Gunkel out of local venues for her shows, temporarily depriving Georgia fans of additional wrestling options and forcing her to close her outlaw operation. As ex-NFL player Wilson described in his book Chokehold, he and Patterson had left Gunkel’s failing promotion in the hopes of starting a racially inclusive promotion that also doubled as a labor union, still a pipe dream even in 2019. “When I got into pro wrestling, I was probably the only wrestler in the country who belonged to a labor union [the NFL Players Association] and knew something” about it, Wilson boasted, though his reform effort died aborning after a lackluster debut show at Atlanta’s Omni Coliseum.

Wilson perhaps exaggerated his grievances with pro wrestling and the extent of his association with the sport, but he did cross paths with lots of outlaw promoters trying to shake up the NWA. He made some appearances for Eddie Einhorn and Pedro Martinez’s Great Lakes–based International Wrestling Association, where he was smartened up by Martinez about the consent decree imposed on the NWA, and also helped International Championship Wrestling owner Angelo Poffo and his sons Lanny and Randy Poffo (later the Genius and the “Macho Man,” respectively) run opposition against Tennessee promoters Jerry Jarrett and Jerry Lawler. Einhorn and Poffo also sued the NWA for monopolistic practices, but those lawsuits came to nothing, and eventually Einhorn was out of business and Poffo’s kids were back in the mainstream fold, feuding with Lawler on Memphis television in the NWA-allied Continental Wrestling Association. Even if these outlaw promoters came up empty, the fans still prevailed: the future Macho Man Savage became an unparalleled force on the microphone during both his real and fictional wars with Lawler, and legendary wrestlers such as Ivan Koloff and Ox Baker gave Cleveland and Buffalo crowds something to boo about when they made frequent appearances for Einhorn’s IWA.

And it’s not as if NWA promoters who weren’t outlaws during this period inspired a higher degree of trust. Georgia Championship Wrestling would enter a brief golden age by signing a national syndication deal with Turner Broadcasting in 1979, allowing programming booked by Ole Anderson and promoter Jim Barnett to encroach—via the miracle of cable television—on other protected markets. Other promotions would follow suit with cable deals, with Joe Blanchard’s Southwest Championship Wrestling securing a slot on the USA Network in 1982 and Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association landing on ESPN starting in 1985. Both Mid-South Wrestling, run by Bill Watts, and World Class Championship Wrestling, owned by Fritz Von Erich, boasted high-quality rosters and entertained thoughts of going nationwide. And Starrcade ’83, a supershow staged by Jim Crockett Promotions and distributed via closed-circuit television, offered a new way forward for packaging and selling wrestling content. It was an all-out slugfest for eyeballs and box office dollars, but the extent of this competition during a transitional period in the sport’s history gave fans an extremely rich variety of wrestling options.

In other words, by the time Vincent J. McMahon was retiring from the business and his son Vincent K. McMahon was preparing to expand the then-WWF’s horizons, all of the territorial promoters were already at each other’s throats. The internal conflict allowed an external competitor to strut right in. He didn’t have to so much take over their territories as do all the little things they weren’t doing—paying their top stars better, convincing minority owners of rivals, like Georgia Championship Wrestling’s Brisco brothers, to sell him their shares, and paying good money to networks like USA so they would drop even a highly-rated show like Joe Blanchard’s cable program. Jack Brisco explained in his autobiography that acquiring his and brother Jerry’s stakes in GCW—which they had originally been given for free in exchange for making appearances to support the NWA in its war against Ann Gunkel—was a foregone conclusion once Vince dangled the right incentive: “Vince asked if we were willing to sell and we him told that we were, if the price was right … [but] what was so amazing about the whole deal was that we were able to pull the entire thing off without anyone knowing about it.”

As GCW booker Ole Anderson made clear in his autobiography, outspending others, even with borrowed money, wasn’t hard: The old-school promoters weren’t as rich as they would have liked others to believe, and they and their employees could easily be swayed with the promise of a quick payday. “[Atlanta promoter and eventual WWF employee] Jim Barnett wasn’t a multi-millionaire, he wasn’t even a one-millionaire … and when Barnett bought Georgia Championship Wrestling, he didn’t put one dime down,” wrote Anderson. On top of disorganized, greedy, and chronically under-capitalized opponents, WWF also benefited from welcome bits of fortuity, like Lou Albano connecting with rising pop star Cyndi Lauper on an airplane flight and hashing out a plan to work together on a music video and eventually a wrestling feud, a story line that gave McMahon a direct line into the MTV generation. Both sides produced their share of memorable matches, but WWF’s innovative promotional strategies helped the company take Round 1 of the feud against the disorganized NWA.

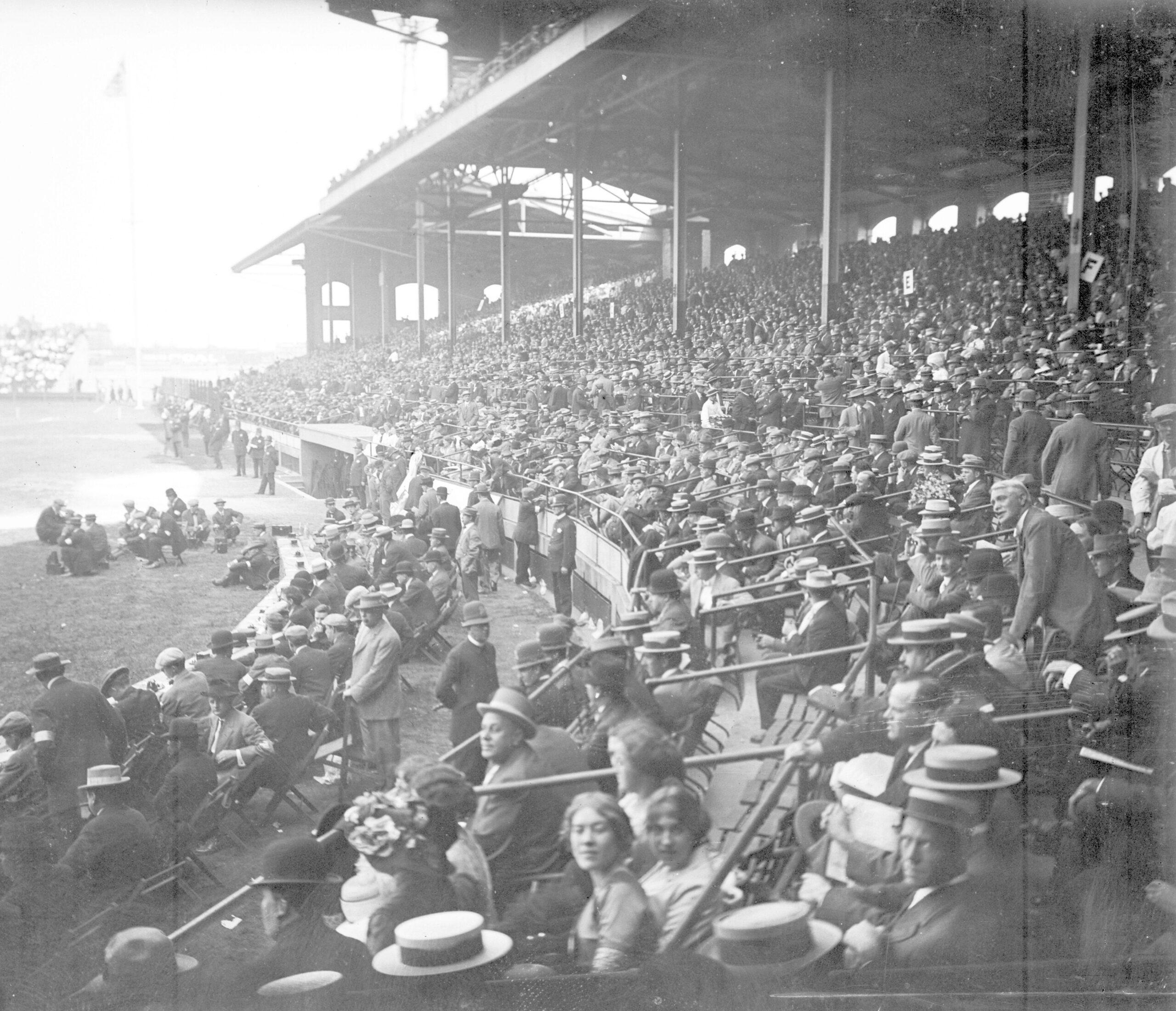

Fierce competition drove some of their weakest members into the WWF fold, enabling men like Toronto promoter Jack Tunney and Calgary promoter Stu Hart to pad their retirement nest eggs in exchange for transferring territorial promotional rights and top talent to McMahon. Meanwhile, the strongest remaining NWA promoters tried to circle the wagons. Verne Gagne, Bill Watts, Fritz Von Erich, Jim Crockett, and Jerry Jarrett attempted to join forces to launch a counteroffensive against the WWF in the form of 1984’s Pro Wrestling USA conglomerate. However, creative differences and short-term thinking shattered the group and they mustered only one supercard, 1985’s SuperClash at Comiskey Park in Chicago, before going their separate ways due to disputes over gate receipts. Isolated once again, these magnates either sold out, like Watts when he made a quick payday by selling his Mid-South Wrestling business and its wrestlers, rebranded as the “Universal Wrestling Federation,” to Jim Crockett Promotions, or let things wind down to the bitter end, as Verne Gagne did with the AWA, which eventually taped its shows on a deserted ESPN soundstage.

But here’s the thing: All along the way, plenty of great wrestling continued to happen. Among other great matches, Georgia Champion Wrestling’s Ole Anderson and Jim Barnett got a fantastic, blood-drenched feud out of Buzz Sawyer and Tommy Rich. Jim Crockett and Dusty Rhodes produced some legendary story lines involving Rhodes and Ric Flair’s Four Horsemen. Fritz Von Erich and bookers Ken Mantell and Gary Hart squeezed a tremendous amount of value out of Von Erich’s doomed sons as well as the various charismatic heels, like the Freebirds, brought in to battle them. Bill Watts built an organization of hard-nosed former college athletes cut in his tough-guy image, launching the careers of bruisers like “Hacksaw” Jim Duggan and “Dr. Death” Steve Williams. And of course there was McMahon, outdoing them all by turning his operation into a technicolor cartoon filled with celebrity cameos and larger-than-life trademarked personas.

And even as the market shrunk, and longtime Dallas manager Gary Hart went to Atlanta to run a villainous stable for the now Ted Turner–owned World Championship Wrestling built around a young Great Muta and a middle-aged yet still supremely-conditioned Terry Funk, the results were memorable. Sure, we fans bore witness to plenty of bizarre garbage, like WCW’s “Ding Dongs” tag team and the various goofy, rebranded characters on offer from Vince McMahon (Terry Taylor as the “Red Rooster,” Lanny Poffo as the poetry-reciting “Genius”). But that was a small price to pay for a chance to watch Bret Hart, Brian Pillman, Shawn Michaels, and other budding stars ply their trade.

The Attitude Era, remembered so fondly by people younger than me, then, was just another piece of a never-ending wrestling war of all against all that rewarded bystanders like me with stellar matches. It was more memorable, perhaps, because it always seemed like a truly fair fight between the rich Vince McMahon and the even richer Ted Turner—but the playing field wasn’t totally uneven in 1983, when McMahon began out-maneuvering more experienced but also more risk-averse competitors. It worked, as Eric Bischoff remarked in his autobiography, because “sometimes war is good,” a state of affairs that drew a combined 8 or 9 rating on Monday nights in 1998 for WCW’s Nitro and WWE’s Raw. By the time the war had heated up, I didn’t have a horse in the race—I just wanted to see up-and-comers like Chris Jericho, who has hung on long enough to main event AEW’s first pay-per-view, get plenty of televised opportunities to work their magic. The rest of it, things like Mark Henry puking in a toilet after being tricked into fooling around with a trans person, were even more forgettable than the “Ding Dongs.” We got the good and the bad, but as in all times of plenty, more good than bad.

And even the less-capitalized opposition to the WWE that tried to hold the line against the juggernaut during the past decade, Total Nonstop Action Wrestling and Ring of Honor, produced their shares of extraordinary matches, giving such current WWE mainstays as Kevin Owens, AJ Styles, and Samoa Joe a chance to receive national exposure for some of the best matches of their career. The idea of TNA or ROH competing directly against WWE never made much sense, no matter how many has-been WWE stars TNA would line the tops of its cards with, but both organizations benefited greatly by positioning themselves as opposition to WWE (even if WWE chugged along without noticing them), generating content and putting fledgling talent in front of fans. And if TNA and ROH hadn’t needed up-and-coming aces headlining their shows, where in the United States could undersized athletes like AJ Styes or Austin Aries have gotten the chance to put on 30-minute wrestling clinics?

Which is all to say that competition in pro wrestling does raise everyone’s game, including all the wrestlers receiving additional opportunities to develop their skills. But perhaps this latest battle, now joined, is the real deal. Perhaps AEW’s bold challenge to WWE will have long legs, and perhaps the companies will successfully split the domestic wrestling market the way the more established, NWA-affiliated All Japan Pro Wrestling and the upstart New Japan Pro Wrestling did in that country throughout the 1970s and ’80s. Giant Baba’s more staid AJPW helped pay the bills for greats like Jumbo Tsuruta and Mitsuharu Misawa, and Antonio Inoki’s NJPW showcased five-star specialists like Tatsumi Fujinami as well as a slew of great, big, heavy-set gaijin wrestlers, bruisers like Scott Norton and Big Van Vader. The two promotions managed to share the market, much as WCW and WWE did for a brief period, and the result was a vast library of matches now living forever in the YouTube archives.

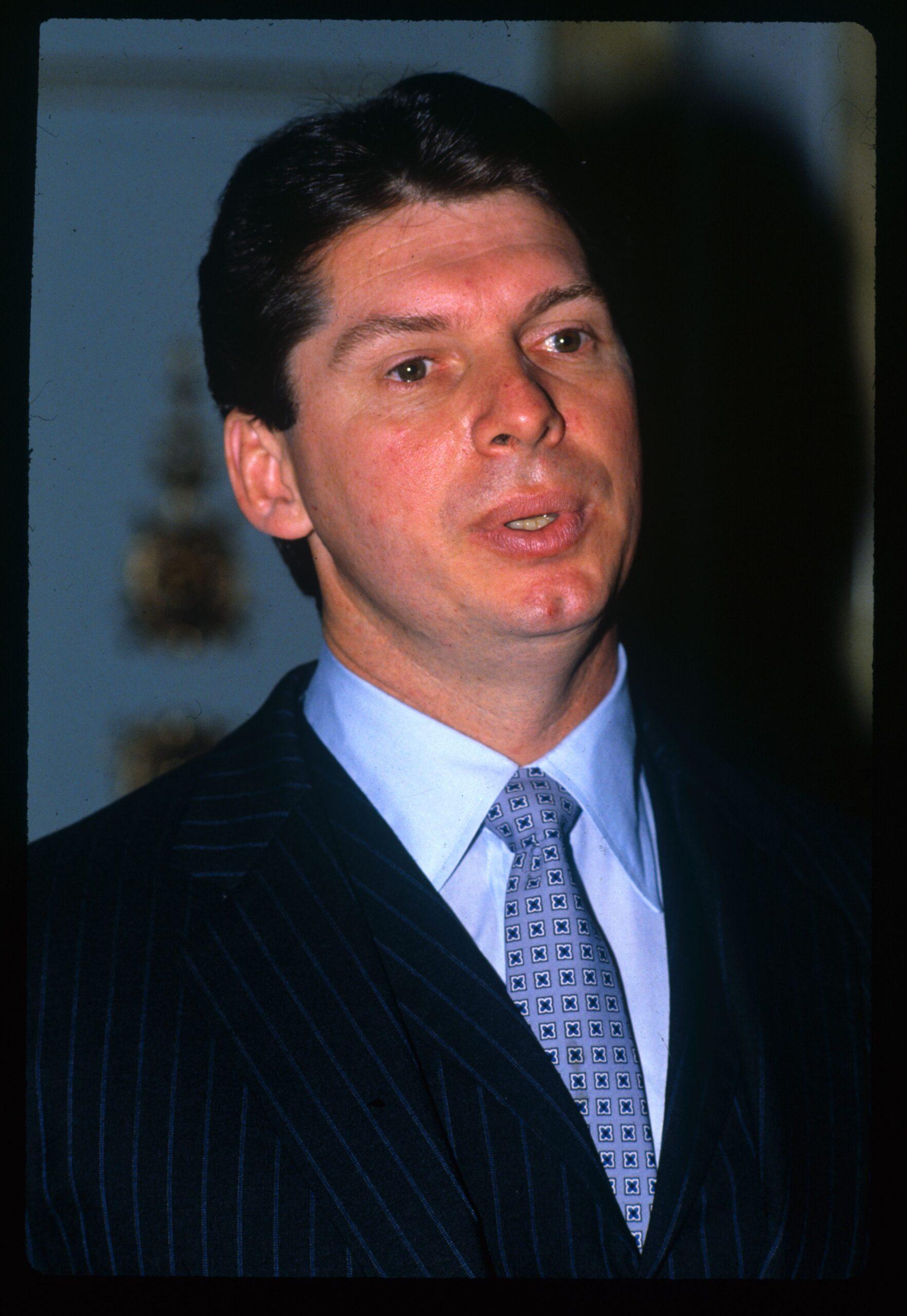

Of course, coexistence—even uneasy coexistence like what AJPW and NJPW maintained—isn’t Vince McMahon’s stock in trade. McMahon’s father, himself the son of a promoter, had come to wrestling merely to take part, but taking over became part of the son’s mythos. Even if it wasn’t as easy or as inevitable as the triumphalist McMahon narrative would have us believe, it was still something he pulled off, and pulling it off against all odds is what created the “Mr. McMahon” character who insults everyone and fires everyone. On a visceral level, much like longtime friend Donald Trump, McMahon needs competition so he can keep demonstrating how he wins big league by crushing said competition. When Triple H responded to fans chanting “AEW” as current AEW producer Billy Gunn joined his D-Generation X stablemates at this year’s WWE Hall of Fame ceremony, he did a fine job of encapsulating McMahon’s approach to business, telling Gunn that he hoped McMahon would “buy that pissant company so that he can fire you.”

And perhaps that will happen, since “buying pissant companies” after competing against them until they’re driven to the point of financial ruin is part of the “Mr. McMahon” brand. Perhaps one day McMahon will purchase AEW, or at least whatever tape library it compiles during its lifespan—after, say, financial backer Shahid Khan, a richer man than McMahon yet a man, like Ted Turner before him, who isn’t defined by his association with pro wrestling, gets cold feet and walks away from a losing proposition. But given the long, rich history of wrestling wars and the many benefits these conflicts provide to fans, let’s hope that AEW’s Fyter Fest and WWE’s Extreme Rules, then, are just extremely preliminary skirmishes in a conflict that will rage across the better part of the next decade.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter @MoustacheClubUS and read more of his work at www.oliverbateman.com.