“When everyone’s super,” the villainous Syndrome explains with a diabolical laugh in 2004’s The Incredibles, “no one will be.” He might as well have been talking about the 2019-20 NBA season.

As the league adjusts to a landscape no longer ruled from Oakland, superstars have taken it upon themselves to explore new superteam possibilities. Anthony Davis and LeBron James joined in Los Angeles. So did Kawhi Leonard and Paul George. And Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving agreed to team up in Brooklyn, at least once Durant recovers from his Achilles tear. Other contenders have also spent the first weeks of the offseason constructing rosters as formidable as ever: The Bucks brought back every key player except Malcolm Brogdon from last season’s historically great team, the 76ers signed Al Horford, and the Jazz nabbed Mike Conley via trade.

But no prospective superteam looks as indomitable as recent iterations of the Warriors. That’s not an indictment of their roster-building strategies—perhaps no other team in NBA history can make that boast—but it means this next season will feature much more mystery at the top of the league than recent seasons. That inspires a question: When was the last time the league enjoyed this much championship parity entering a season?

It depends how you try to answer; any way you do, though, requires going back at least beyond when Durant joined the Warriors. In each of the past three preseasons—or, each season the Warriors had KD—Las Vegas gave Golden State better than even odds of winning the championship, per the archival data on Basketball-Reference. The site’s preseason championship odds date back to 1985; no other team in the entire set can say that.

Granting that Vegas’s formulas might have changed in recent years, if not the preceding decades, that means the 2016-17, 2017-18, and 2018-19 Warriors were the biggest preseason title favorites in recorded NBA history—even more than Jordan’s Bulls and LeBron’s “not five, not six, not seven” Heat and the Shaq-and-Kobe Lakers. Here’s every team since 1985 with an implied title probability of better than 1-in-3 entering the season:

NBA’s Biggest Preseason Favorites Since 1985

Unsurprisingly, no 2019-20 team is anywhere close to that level of favorite. After their late-night coup to grab Kawhi Leonard and Paul George, the Clippers now lead the way, with the Westgate SuperBook pegging their odds at +300, or an implied probability of 25 percent. If they enter the season without boosting their odds any further, they’ll have the lowest championship odds of any favorite since 2008-09, when the Lakers and Celtics were joint favorites at +350, or 22 percent.

By that simple measure, then, this is the most wide-open title race since 2009. Yet it makes sense to look beyond the top team, because it seems like the 2019-20 title race will be characterized by the sheer number of possible champions. Right behind the Clippers, Westgate places the Bucks, coming off a 60-win season with the reigning MVP, and the LeBron-and-Davis Lakers, each at 17 percent; and then the supersized Sixers, at 11 percent.

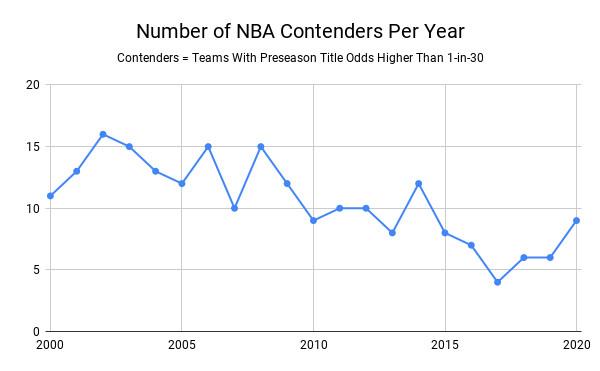

If the NBA had true parity—meaning every roster were exactly equal in talent—all 30 teams would enter the season with a 1-in-30 chance to win the title, or 3.3 percent. So one easy way to define a realistic contender is to say that it’s any team with preseason odds above 3.3 percent. That designation also fits with league history: The most surprising champion since 1985, by preseason odds, is the 2015 Warriors. That’s a shocking discovery in retrospect, but at the time, the Warriors had just hired a new coach in Steve Kerr, were still starting David Lee, and hadn’t advanced to the conference finals as a franchise since 1976. Entering the 2014-15 season, then, Golden State was +2800 to win the title, which translates to a 3.4 percent probability.

Nine teams right now are above the 1-in-30 baseline for a contender, by Westgate’s odds: the Clippers, Bucks, Lakers, 76ers, Rockets (8 percent), Warriors (8), Jazz (7), Nuggets (7), and Celtics (4). Based on the way the upcoming season is being cast, one might expect that this is a historically large number. But it’s actually quite small, meaning the league still projects for a rather compressed title chase.

This graph comes with the caveat that, again, Vegas might have changed the way it doles out odds, which could explain some of the decline over the past half-decade. Yet the trend line is also fairly clear: Even if 2019-20’s contender pool is relatively larger compared to the seasons with Durant on the Warriors, it’s still small when viewed through a wider lens.

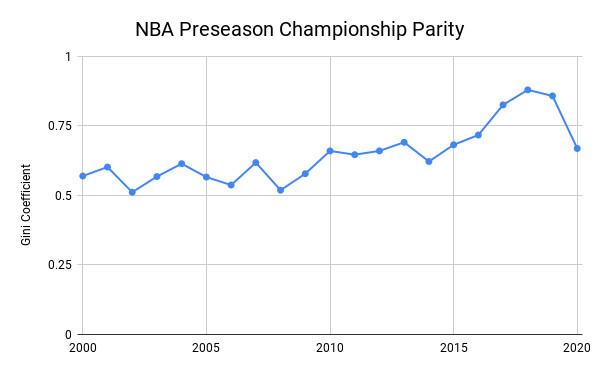

The same sort of finding appears with another test of parity: the Gini coefficient, which is a tool economists use to measure income inequality in a civilization. Gini works on a 0-1 scale in which 0 means everyone is perfectly equal, and 1 means one person holds all the society’s wealth. (The United States, for reference, is around 0.5 on this scale, which is near the high end of the known world.) We can use the same calculation here to determine the (in)equality in the distribution of the league’s title odds.

Similar to the above graph, a chart of the Gini coefficient for all 30 teams’ Westgate championship odds shows that the 2019-20 campaign should have more parity than the past three seasons—but less parity than most seasons before the Warriors warped the collective understanding of NBA favoritism. Here’s the Gini for each preseason since 2000. Remember: Lower numbers mean more equality among the group, and higher numbers mean more inequality.

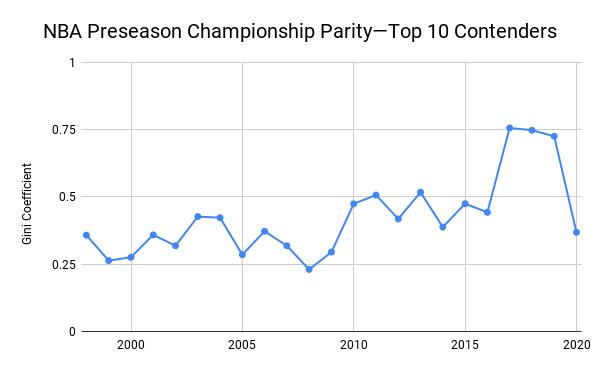

One issue with this graph is that if the league’s worst teams are truly terrible—stand up, Hornets and Wizards!—they could skew the results with their incredibly long odds. Indeed, per Westgate’s current 2019-20 odds, 15 different teams have a 1 percent implied chance or less. But when we talk about championship parity in the NBA, we’re not typically thinking that every team has a chance, just that a healthy number do—and that no one team dominates the probability pie. So let’s instead look at the Gini coefficient for just the top 10 teams in each season for a better representation of preseason projected parity at the top of the league.

The number for 2019-20 as the odds currently stand would be the lowest since 2009. That’s better—but looking at the graph, the same kind of general pattern emerges. The past three seasons are the outliers; 2019-20 is just a reversion to the league’s usual shape. You could argue that the upcoming season will feature unprecedented parity, but you’d really have to squint and engage in selective fact-finding to see it.

Not that this broad outline for a season is a bad thing. In the NBA, inequality generates fan interest; over the past few decades, TV ratings, for instance, have been much higher for Finals in lower-parity periods. According to the viewership numbers at Sports Media Watch, the lowest-interest Finals of a recent vintage came in the period from 2005 to 2009—which slots right between the breakup of the Shaq-and-Kobe Lakers and the start of the superteam era, via the Heat’s Big Three, when no team lasted several years as a dominant force.

Average NBA Finals Viewership

If anything, then, the 2019-20 landscape embodies a happy medium between too much parity and too much singular dominance by one team. The main forward-looking questions after the flurry of early-July moves aren’t Which teams are good? or Which teams can possibly challenge the Warriors? but which of the near-dozen good teams are good enough to win a title, and how their new lineups will jell, and how the league’s broader stylistic trends—the continued 3-point boom; the possible return of the big man—might shape the contours of the coming season.

Had Leonard gone to the Lakers, all of this discussion might be moot; a James-Davis-Leonard trio might have resembled the Durant Warriors in Vegas’s view. Instead of a Big Three, the league now has a bunch of Big Twos and Sizable Fours and Well-Constructed Fives that will grapple on much more even footing. They’re all trying to be super. But none is strong enough, yet, to make all its competitors look weak.