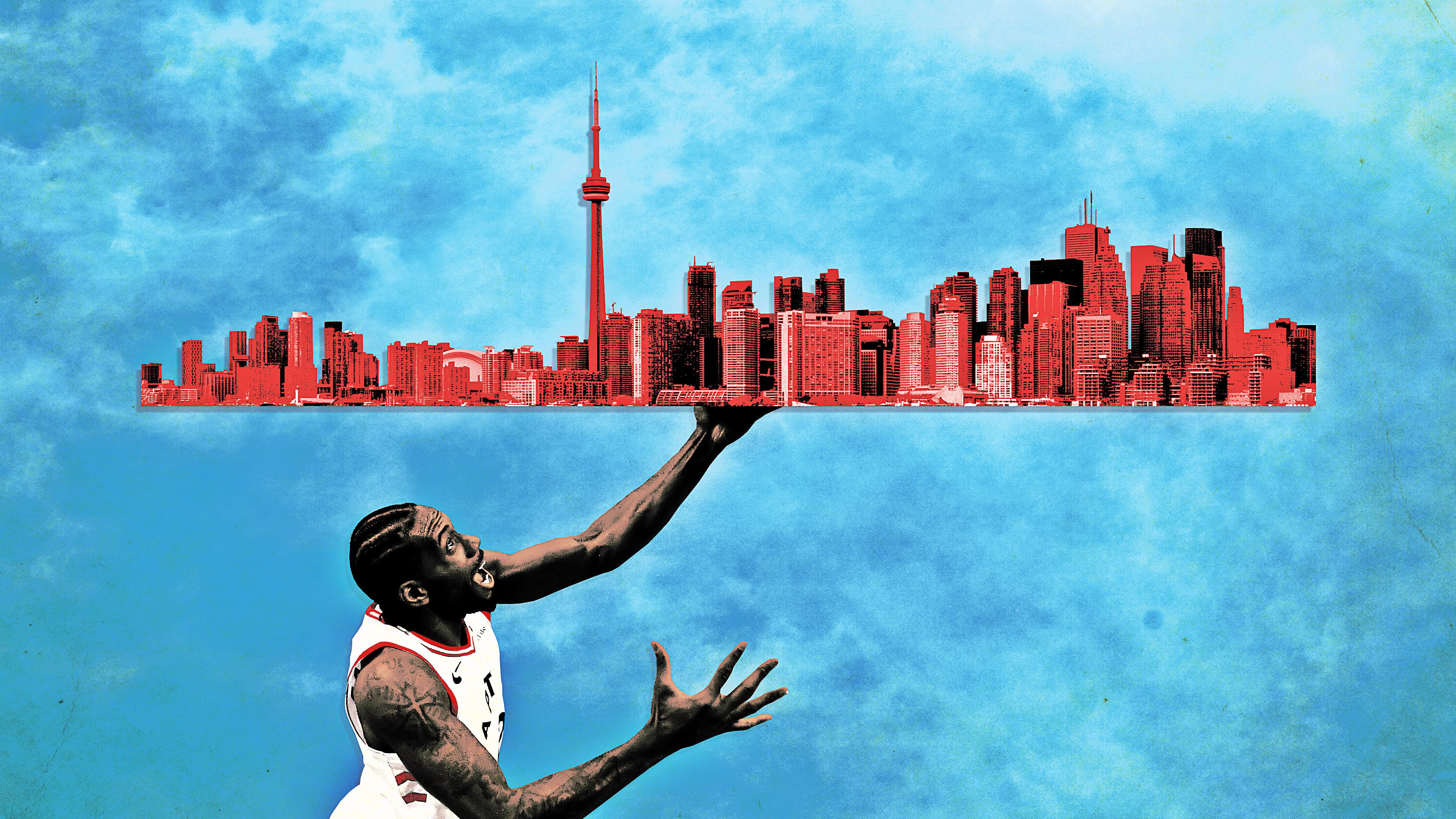

Northern Exposure: Toronto Is Now the Center of the Basketball Universe

With their first NBA championship after 24 years, the Raptors are no longer the “other” team—to the Maple Leafs, to American franchises, or to the United States in generalToday, in Toronto, it’s not cold. It is cool, in the mid-60s, but perhaps the collective labored exhalations of Raptors fans will make the thermometer jump even a little higher. For decades, the fandom has been muffled—by more established sporting cultures in Canada, by apathy, by losing. But now, Toronto is home to a title, and the fandom has been freed: Turn on the television, go on Twitter, maybe just turn your ear toward Niagara Falls and listen closely, and you’ll know that Toronto is now a basketball city.

Surely you’ve seen the video clips and pictures of the dozens of similar outdoor enclosures, nicknamed “Jurassic Parks,” erected throughout Canada for Toronto fans to watch the NBA playoffs. At many of them, the scenes have been raucous, joyous, and on the rare occasion, ugly. Telecasts revealed where each Jurassic Park began, but not where they ended.

In the Raptors’ 24 years of existence, the team has bounced between admirable also-ran and total irrelevance, cultivating a fan base that is notably devoted if famously paranoid. Now, with their first Larry O’Brien Trophy in hand, that cynicism, perhaps, has melted away. Even in the United States, the center of the basketball universe has migrated north of the border. “I think there’s some real heartfelt pride,” Raptors head coach Nick Nurse said of Toronto before Game 1. “This is a big city. And a first time. And I think the first time always makes it seem like there’s a little more energy.”

The Raptors appeared close to inevitable in their 4-2 Finals win against the Warriors. Golden State has lost before, but it’s never looked as flustered and vulnerable as it had in these Finals. Their two wins came by a combined six points, and Toronto outscored Golden State in 17 of the series’ 24 quarters. By the end of the series, the Warriors’ roster looked as shallow as it’s been at any point over their five-year dynastic run. Kevin Durant played just 12 minutes in the series, rupturing his Achilles tendon in Game 5, and Klay Thompson tore his ACL in the conclusive Game 6. By the closing moments of the final game ever to be played in Oracle Arena, Golden State didn’t look beaten; it looked broken. The two-time defending champion, somehow, eventually became an underdog; part of that can be chalked up to rotten luck, but it is also a testament to just how far the Raptors had come from their years as lovable losers. “As the Raptors are now growing, it becomes an identity thing for a huge number of people in the city,” says Bruce Arthur, a columnist for the Toronto Star who has written about Toronto sports for nearly two decades. “It’s a pretty big place to be.”

This is the first time that one of the major three Toronto sports teams has won a title since 1993, when Joe Carter’s legendary walkoff home run clinched the World Series for the Blue Jays. The Raptors’ run to the title, perhaps the least likely in the history of the league, marks more than just the end of the area’s decadeslong title drought. It is a culmination, completing Toronto’s transformation into a full-fledged basketball city.

Thirty years ago, none of this existed. There were no Jurassic Parks, no “We the North” rallying cries. Canada kept basketball at a distance, with few people following it and even fewer top talents emerging; Steve Nash, the now–Hall of Fame point guard who grew up in British Columbia, had barely begun to play the sport. “Basketball in this country, you always felt like you were part of a small tribe,” Arthur says. “You knew the other people who were in it when you met them, and yeah you were passionate about it, but there were like five kids at my high school who watched basketball and they were all on my basketball team.”

In the early 1990s, before the NBA’s expansion into Canada, information about the league came at a premium in the country. The media institutions had an established hierarchy of priorities: Hockey grabbed the first, second, and third segment of every televised sports program. To discover what had happened in the NBA draft, Canadians had to search for a newspaper that deemed the event worthy of coverage.

In 1995, when the Raptors and the Vancouver Grizzlies played their inaugural seasons, the organizations were part of an experiment. Could the NBA come to a new country and make itself important? In Vancouver, the answer was no. The Grizzlies hardly left a mark on the city and moved to Memphis on the heels of six losing seasons in 2001. For a while, it seemed the Raptors would also struggle to captivate local crowds. They played until 1999 in the SkyDome (since renamed the Rogers Centre), a stadium built for the Blue Jays and comically ill-fitted to host basketball. Ticket sales were not a problem, but cultural integration of the game was a different story.

But the Raptors emerged as a team for new Torontonians, transplants and kids and a generation looking to forge its own identity. “People my age, there was perceived ownership of the Raptors because basketball was this new sport to the city and the team didn’t belong to a different generation of people,” says Eric Koreen, 34, a native of Thornhill, Ontario, who covers the Raptors for The Athletic. “The Raptors felt slightly more accessible than the Leafs. You could get a ticket for 5 or 10 dollars whereas the Leafs, you had to know somebody or your parents had to splurge once a year.”

Most Torontonians will tell you that Maple Leafs fandom is woven through every centimeter of the city’s fabric. The team was established in 1917, and ties to it have been passed down from grandparents to parents and beyond. When the Leafs travel to play other Canadian NHL teams, they often fill swaths of the opposing arenas. “It is a dominant monoculture in this town,” Arthur says. “And it’s old money and it’s old prestige and it’s old power. It’s the dominant force.” But the Leafs have largely underwhelmed during the formative years of younger Torontonians. The team hasn’t reached the conference semifinals of the Stanley Cup playoffs since 2004 and hasn’t lifted the Cup since 1967. Their appeal outside of Canada, too, has met a sort of cultural ceiling. “The Raptors punctured America in a way that the Leafs never could,” Koreen says.

That started with Vince Carter, who was perhaps the NBA’s first viral superstar. His springy legs created some of the defining moments of the highlight era. Talk to any basketball fan old enough to remember the turn of the millennium, and they’ll mention the 2000 dunk contest and Carter dangling from the rim by his elbow. But Carter’s dunks weren’t enough to lift the Raptors from being a mild fascination to a point of pride for Torontonians. The early Raptors never advanced past the second round of the postseason, famously falling to Allen Iverson’s Sixers in 2001 after Carter missed a last-second, off-balance jumper in a Game 7. “There was obviously a lot of excitement over the dunk contest, but it was not nearly to the scale that it is right now,” Yang-Yi Goh, a Toronto-based freelance writer, says. Carter made the Raptors cool; it would take winning to make them resonant.

A fan base will cherish a run of sustained success for a lifetime. Ask Celtics fans about the 1980s, Knicks fans about the ’90s, or Lakers fans about the Showtime or Shaq and Kobe years. Even without a title, a lengthy period of success can engender goodwill in a city that spans a generation. Toronto’s Finals run would have been a boon at any point in the franchise’s history, but that it happened right now is almost too perfect.

Over the last six seasons, the Raptors haven’t missed the playoffs, and have topped 50 regular-season wins four times. During the Carter years, the team made the second round of the postseason only once. During Chris Bosh’s seven seasons with the team, from 2003 to 2010, they didn’t even manage that much. Since 2014, the Raptors have established themselves as an Eastern Conference mainstay. “This is the beginning, these last five or six years, of it becoming something closer to Canada’s team, crossing into the national bloodstream,” Arthur says.

Despite what the zero-sum conventional wisdom of modern NBA front offices might dictate—that if a team isn’t a contender, it’s best to dismantle and rebuild than hope for a lucky break—there has been cultural value in the Raptors’ sticking around. Each of their playoff runs brought a spark of energy to a city that took a while to fully familiarize itself with the sport. “This is how fan bases get built,” Arthur says. “The Jays came into this country and won two championships in the early ’90s and when they’re bad, people don’t pay attention. And when they’re good, it’s as deep a well of fandom as anything in the country. That’s kind of where the Raptors could get to and this is how you get there.”

The final checkpoint in getting there long proved elusive. Over the Raptors’ run of postseason appearances fueled by star forward DeMar DeRozan and head coach Dwane Casey, the franchise gained a reputation for shrinking in the biggest moments. Toronto was eliminated by LeBron James’s Cavaliers in each of the previous three seasons; a conference final in 2016, and two conference semifinals that both ended in sweeps. The city morphed into a meme: LeBronto. By last season, confidence in the team was strikingly low; the Raptors finished 2017-18 with the best record in the East, but the refrain remained the same: Don’t worry about them. Toronto’s Toronto.

That’s all changed with this exceptionally dramatic playoff run. Toronto trailed in every series through the first three rounds before storming back to win. In the conference finals, the Raptors fell into an 0-2 hole before rattling off four straight. In the clinching Game 6, Leonard dunked over likely league MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo in what seemed like the release valve for all of the uncertainty that had built up in Raptors fans over the years.

But one moment from this run will be replayed in bars across the city, province, and country more than any other: In Game 7 of the Eastern Conference semifinals against the Sixers, with the clock ticking toward zero, Leonard attempted a mirror image of the shot that Carter had missed 18 years prior. It touched the rim four times, refusing to drop for nearly two seconds, long enough for the crowd in Scotiabank Arena to go silent. Then it fell through, giving the Raptors the game, the series, and a memory to cling to for posterity. “The one thing with the Raptors you’ve always got to remember,” Arthur says. “This is the first time they’ve rewarded their fans with the moments that are ‘I remember where I was.’”

Leonard’s shot didn’t just spawn blog posts about the moment, it spawned blog posts about photos of the moment. The Shot was of such dramatic and competitive magnitude that it reversed years of conditioning that had made Torontonians afraid to care about or believe in the Raptors. “I think Kawhi’s shot was the turning point for the bandwagon this year. People like my mom, who is very sports-averse, started texting me about the Raptors and caring after that shot,” Goh says.

The Shot had a ripple effect that lapped over the edges of the basketball pond; part of becoming a basketball city is becoming a fixture of the cultural world that surrounds the sport. So it makes sense that as the Raptors have broken through, other stories about Toronto have too.

“NBA success is a big vacuum for media from all over the world, so when you make the Finals, one side effect is that you have 300 or more media people staying in your city,” says Sam Anderson, who authored a 2018 book called Boom Town about Oklahoma City and the rise of the Thunder. Much of Anderson’s book details how a rapidly ascendant basketball team brought the eyes of the world onto a new city. Toronto is a different scale of place than OKC; it’s larger by a factor of 10. Nevertheless, it is getting the same type of basketball bump.

“Very influential, well-situated people with media platforms are now in your city dealing with the logistics of ‘Where do I get a cup of coffee? Where is a decent place to eat?’” Anderson says. “And these are people who are trained to pay attention to where they are, so all of that energy now is directed to your city. And they are all competing for ‘How do I tell this story differently than everybody else?’ And some of that becomes a story about the city.”

Much of that energy has zeroed in on Drake. The biggest rapper on the planet has been sitting courtside at Raptors games for years now, often creating an escalating show of his own. In the 2014 playoffs, he lint-rolled his pants. In 2016, he tried to stare down Durant while he checked into a game. This year, Drake kicked things into overdrive, rubbing Nurse’s shoulders during the conference finals, wearing a Dell Curry Raptors jersey to Game 1 of the Finals, and generally doing his best Spike Lee impression throughout the playoffs. In a way, Drake’s presence has supercharged the organization. “There is a weird symbiosis between the rise of Drake and the rise of this basketball team. That was something Oklahoma City didn’t have: a major celebrity sitting courtside,” Anderson says. “Basketball has the most juice right now. I think the rise of hip-hop as the dominant cultural mode, the crossover between that and basketball has been pretty seamless.”

The success of the Raptors has allowed other parts of Toronto’s cultural identity to permeate the discourse as well. Over the last few weeks, the city’s ethnic diversity has been championed (more than half of the city’s population speaks a language other than English or French) and dissected. At The Ringer, my colleague Danny Chau’s January reporting trip to the city was accompanied by a dispatch on its rich and varied food scene. Through watching the Raptors, non-locals have perhaps heard about facets of Toronto’s film or architectural culture; that’s what sporting success can do for a city. “Maybe Kawhi and this team is the gateway for some people,” Koreen says. “But Toronto also has one of the most important film festivals in the world and it also has Caribana over the summer and there are tons of huge events for people who aren’t sports-obsessed.”

Of course, increased visibility also brings pitfalls. During Game 5, when Durant tore his Achilles, parts of the Toronto crowd cheered, waving and taunting the injured forward. Both Raptors and Warriors players scolded the relevant parties afterward, and as KD left the court, much of the arena applauded him and chanted his name. Just as the Raptors have served to spotlight all that makes Toronto special, they’ve also brought attention to its capacity for unsightly behavior (these are sports fans, after all). Since Game 5, the fan reaction in that moment became one of the biggest media stories surrounding the Finals. “I think it was the first time the world had been paying attention to what Raptors fans had been doing in a negative sense,” Goh says. “Maybe it was the first time that people had to reckon with the fact that the Raptors fan base is no better than any other fan base.”

While there has been a dark side to Raptors Mania, though, the conscientious excitement is what will endure. Nearly half of Canada watched at least part of the Finals; ratings for Raptors games swamped those for the Stanley Cup, and many new fans say they intend to stick around next year. “I’m getting texts from friends in Vancouver who are in bars and the sound is up for Raptors playoff games, and that never happens. Like never. Even the last few years when they were good and playing LeBron in the conference finals, it didn’t happen,” Arthur says. “The further they go, the more casual fans tune in because they want to be there for the next thing.”

The next thing, now, is another title. Just 24 years after adopting basketball, Raptors fans get the ultimate privilege: the opportunity to root for a title defense.

Kawhi Leonard is the hand that turns the page. He isn’t omnipresent, but when he appears he can feel inevitable. He doesn’t talk much. He simply materializes and wipes the slate clean. Leonard closed the book on Miami’s mini-dynasty, and now he has done the same to Golden State’s. When the NBA has recently needed to enter a new phase, Kawhi has been the willing usher. Now, Toronto is along for the ride.

“DeRozan could never provide such economical production, but he isn’t alone. Neither could the other franchise players in team history, from Vince Carter to Chris Bosh to Kyle Lowry, the five-time All-Star who’s lately transformed himself into a role player on this Leonard-driven squad,” read a column in the Star from May. “This is as good as Toronto has ever seen.” As the playoffs wore on, Toronto didn’t need a superhero like Carter as much as it needed somebody to parallel its own story. Vince forced his way out of town; Kawhi forced his way in.

The Raptors and their fans have long been the other. Other to the Leafs, other to American teams, other to the United States in general. Canadians, Koreen and Arthur both emphasize, often view themselves chiefly through the lens of not being American. DeRozan was a star and was beloved, but Leonard’s otherness among NBA stars—LeBron has a production company, Jimmy Butler has a YouTube channel, Kawhi has sent four tweets—better reflects the Raptors’ image and Toronto’s psyche.

“People really identified with DeMar and loved DeMar, and I think that he is, in some ways, the way that we are: emotional and hard-working and prone to reacting badly to criticism,” Goh says. “I think that Kawhi’s identity is what this town strives to be, and the way that they want to think of themselves going forward.”

Now, with his free agency looming, Leonard can choose Toronto and cement their collective identity. “People are excited, and then the team fuses with the identity of the city and so people feel proudly a resident,” Anderson says. “Not just that’s where they happen to live, but that is an identity to parade around the world and be proud of. And so, there is something to this collective mythology that the people can believe in and get really excited about.” If Leonard stays, he will be a legendary figure in the city forever. But perhaps even if he leaves, for Los Angeles or elsewhere, his reputation will remain unimpeachable. After all, he’s already given a fan base something they didn’t even know they wanted from him just a year ago.

There is a parade on Monday in Toronto that nobody was expecting, but tens of thousands of people will be there. The town will be red, and the crowds will contain the totality of a city; its beauty and its quirks and its conventions. Toronto is having its day; for the moment, the rest of the world will have to be the others.