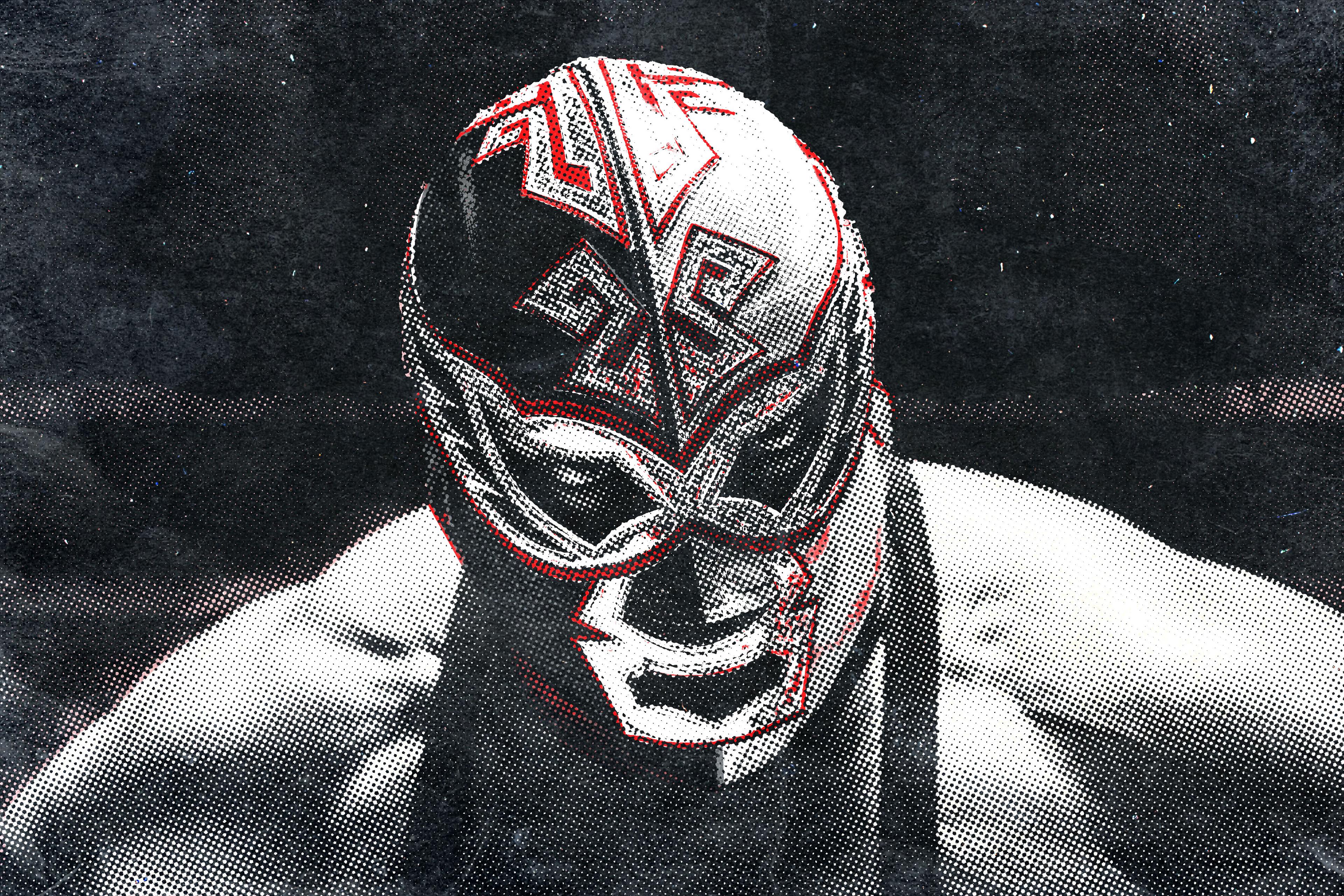

César Cuauhtémoc González Barrón, the second-generation lucha libre star who wrestled under the name Silver King and played the chief antagonist in the movie Nacho Libre, collapsed and died last week in a London wrestling ring. Silver King’s final act was heartbreaking: In a match against Juventud Guerrera—the now-44-year-old “Youth Warrior”—the stocky Silver King, visibly fatigued, collapsed flat onto his stomach, but not before Guerrera gave him one weak final knee before allowing his rival to slump to the ground. Afterward Guerrera struggled to turn Silver King’s dead weight, finally securing the pinfall. Guerrera celebrated, climbing the ropes and triumphantly raising his arms, while Silver King remained incapacitated in the center of the ring, the victim not of a knee or any other wrestling move but, apparently, a heart attack. A minute or so passed, and then a host of other famous luchadors, including El Hijo del Santo and El Hijo del Fantasma, rushed the ring to assist their fallen comrade. Their efforts proved unavailing. Silver King died.

The second-biggest myth of the wrestling match, after the fact that it is meant to be taken as real, is that it is utterly fake—scripted, safely executed by trained professionals, and occuring in a hermetically sealed environment in which time can stand still. A sexegenerian hero like Hulk Hogan can win forever, even well into his dotage, if the booker holding the “pencil” says it will be so—and the fans signal their acceptance of the result with loud applause. But this second-biggest myth, just like the biggest myth, is always in the process of being exploded. One documentary story after another, from Beyond the Mat to Viceland’s recent take on the life and times of Bruiser Brody, tells us that wrestling will kill you; so too do obituaries for fallen, broken idols like Tom “Dynamite Kid” Billington and “Mr. Perfect” Curt Hennig.

But what they do not tell us is that wrestlers can die right in the ring like Silver King, right before our very eyes, and the use and abuse to which they have subjected their bodies can sometimes have nothing whatsoever to do with it. Even casual fans can recall when Owen Hart, the most athletically gifted member of the Hart family, fell 70 feet to his death at WWE’s Over the Edge pay-per-view in May 1999. This was a moment in which the crowd in attendance had to watch as wrestling’s amped-up, fictionalized hyper-reality went by the wayside—reality, in the form of an unexpected mechanical failure, had strangled Vince McMahon’s sports entertainment fiction.

Hart’s death may have marked the beginning of the end of the Attitude Era, or at least the end of the beginning, but it wasn’t representative of how wrestlers typically die in the squared circle. The wrestlers who have died in the ring typically die the way Silver King did, suffering a myocardial infarction and being left to grasp helplessly at the tightness or pain in their chest while those around them struggle to comprehend. Wrestlers, in other words, die the way so many people do—the way my uncle, a stocky 57-year-old diplomat working in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, died, dropping dead suddenly in the gym while lifting weights, a terse coda to a life devoted to fitness and exercise.

They die, in other words, the way trailblazing African American Luther Lindsay did, his dead body draped across opponent Ronnie Paul for a final 1-2-3 during a 1972 encounter. Lindsay, a 6-foot-4 mountain of muscle who allegedly gave even skilled shooter Stu Hart fits in Hart’s practice “dungeon,” succumbed to an unexpected myocardial infarction—a cardiac event so dramatic and ill-timed that it left no window for medical responders to resuscitate him. But it did leave Lindsay, like Silver King, enough time to keep kayfabe: each concluded the match and brought down the final curtain.

For men like British tough guy Mal “King Kong” Kirk, a 300-pound ex-rugby player, bringing down the curtain was how he paid his modest bills. Like a host of other British super heavyweights, he worked the Joint Promotions circuit, putting over the even heavier and extraordinarily popular Shirley “Big Daddy” Crabtree. But unlike the rest, when Big Daddy gave him a signature big splash for the pinfall in 1987, Kirk didn’t rise to fight another day—he died of a myocardial infarction, expiring underneath Big Daddy’s immense bulk. Ilona Kirk, Mal’s wife, told author Simon Garfield in The Wrestling that “Mal’s job depended on making Big Daddy look good in the ring … he got paid 25 pounds a night for being hurled all over the canvas, but if he fought Big Daddy, he got an extra five pounds.” The work, at least for Kirk, was hardly a labor of love. “His last words to me before he left the house were, ‘I don’t want to go. I hate this job.’”

Mike DiBiase, a star AAU and NCAA wrestler and the adoptive father of “Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase, was a different story. By all accounts, he loved wrestling, and even defended the honor of his sport in a legitimate boxing match against all-time great Archie Moore, getting KO’d unceremoniously in three rounds. DiBiase, another grappler of stocky but athletic build, entered his final match in 1969 in poor health. Set to face the immobile, 500-pound Man Mountain Mike—a touring freak attraction and one of several grapplers who used a “Man Mountain” gimmick—DiBiase struck Harley Race, who was at ringside, as exhausted and ill. According to his autobiography, Race urged DiBiase to call off the match and get some rest.

But DiBiase believed the show must go on, and it did. “As I watched the match, I saw DiBiase grab his chest and fall,” wrote Race. “The referee froze, not knowing whether he should start the count. (That’s part of a referee’s job when someone is injured in the ring.) I ran into the ring and started administering mouth-to-mouth and CPR on DiBiase. But it was too late.”

DiBiase had died of a myocardial infarction, a massive heart attack that Race believed “probably started before he stepped into the ring.” Thirty years later, Gary Albright—a 300-pound suplex machine and former NCAA wrestling standout who shared an alma mater, the University of Nebraska, with DiBiase—also died of a heart attack while clasped in an opponent’s submission hold. But unlike DiBiase, Albright was quickly pinned before resuscitation efforts began.

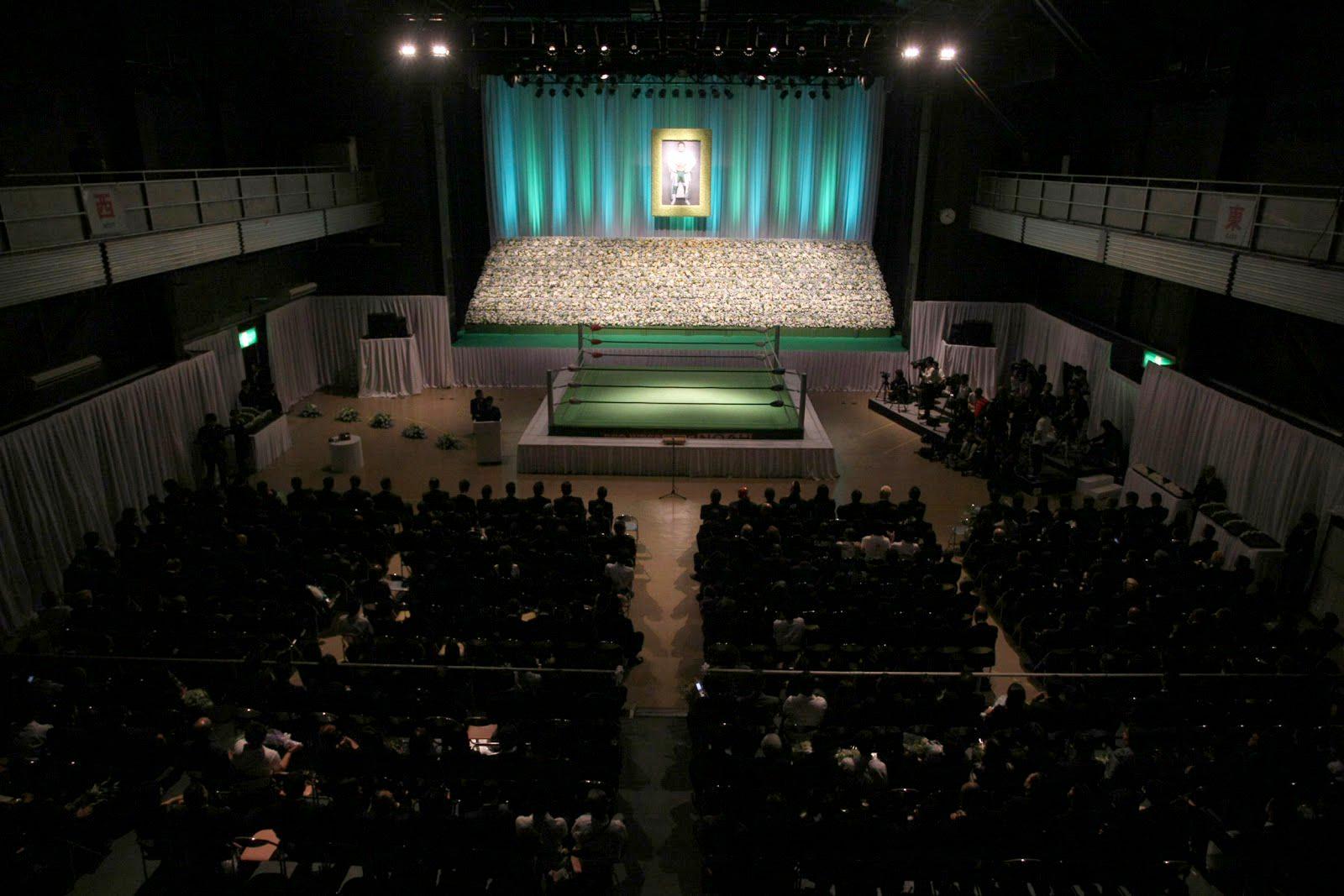

For some truly dedicated grapplers, like once-in-a-generation workrate legend Mitsuharu Misawa, every moment in the ring must crackle and every move not only must count but absolutely must snap, crackle, and pop in that masochistic, Tom Billington–esque style. Misawa innovated many moves but also gained notoriety for the way he absorbed them, becoming known as the “king of the sell” for his all-in approach to emphasizing the power of opponents like Jumbo Tsuruta and Steve “Dr. Death” Williams. By 2008, a year before his death, Misawa had slowed considerably. He was booked in a tag match against Shinsuke Nakamura and Hirooki Goto. “I was just—the only thing I can say is I was shocked, you know? Back then, you could tell just by looking at him that Misawa seemed in poor condition,” Nakamura wrote in his autobiography, King of Strong Style.

A year later, while tag teaming with Go Shiozaki, Misawa absorbed a belly-to-back suplex from Akitoshi Saito and then lay unconscious in the ring until medics transported him to a hospital. “His death sent a shock wave through the wrestling community,” wrote Nakamura. For men like Misawa and Nakamura, along with many other hard-hitting Japanese wrestlers, the comforting myth that wrestling is “fake” and thus somehow safe was obviously false: “It made us realize that we make our living going face to face with death.” For them, as for “King Kong” Kirk, they understood that this was a hurt business, with each wrestling body having only so many notches on its “bump card.”

Misawa’s death came at the tail end of two decades of extraordinary physical punishment, but he wasn’t alone in dying after a multitude of blows. Plum Mariko, a female wrestler who exhibited a similar willingness to absorb larger opponents’ most fearsome maneuvers, died in 1997 at age 29, on the receiving end of an opponent’s powerbomb that put her into a coma. Her death a day later, wrote wrestling journalist Mike Lorefice, resulted from an abscess on her brain that had developed not from one bump but from a litany of them. And that sort of death can sneak up on anyone, including largely unknown young workers like 21-year-old wrestler Matt Lowry, who died in the ring while training, suffering from brain bleeding much like Plum Mariko.

But what about the competitors who stand in the ring with these victims? For most bystanders, the death of an opponent in the ring is something to live down, not something to use as marketing material. But that wasn’t how it worked out for 6-foot-5, 300-pound Ox Baker, a great mic worker and a truly striking physical presence who was on the other side of a pair of deaths that occurred not long after his opponents had finished wrestling him. In 1971, Alberto Torres died of a ruptured appendix three days after a tag match against Baker; this death was quickly attributed by promoters to Baker’s distinctive “heart punch” finisher, elevating it above similar “heart punches” employed by contemporaries like Stan Stasiak.

A year later, Baker wrestled former amateur great Ray Gunkel, then in his late 40s and suffering from the early stages of heart disease. Baker may or may not have caused the blood clot that killed Gunkel, who died in the locker room shortly after the match, but the kayfabe narrative was fixed: Yes, Ox’s “heart punch” could actually kill you. And Baker, his promos all gravelly threats and his T-shirt setting the terms of debate—“You will hate me”—became able to enrage the crowds who assumed he was going to murder their local stars right before their eyes. After all, he had supposedly done it before.

One of the nation’s most notable suspected killers, the neurosurgeon Sam Sheppard—who was accused of killing his wife, a story that may have served as the inspiration for the television series The Fugitive—also played on his notoriety and did a turn in the ring as a pro wrestler after his release from prison. The 45-year-old Sheppard enjoyed a 40-match career, billed as “Killer” Sam Sheppard and finishing opponents with his signature “mandible claw” (later used by Mankind). He appeared destined for bigger things when alcoholism and the resulting liver failure led to his death only a year later. Although this alleged murderer didn’t die in the ring, he, like Ox Baker, brought the aura of death with him—for one night only, folks, this is going to be realer than real!

Of course, most wrestlers aren’t going to die in the ring like Silver King and Mitsuharu Misawa. Even the most committed longtime troupers like Ric Flair, in chronically ill health and sporting badly-damaged bodies, usually defy the odds and escape their late-life matches largely unscathed. Jerry “the King” Lawler, who had a heart attack on WWE Raw back in 2012 not long after wrestling a tag match in which he absorbed repeated elbow drops to the chest from Dolph Ziggler, rebounded to continue throwing fireballs and working matches on the independent circuit. What’s remarkable, perhaps, isn’t so much that wrestlers have dropped dead in the ring, but that even in such an inherently unsafe sport as this one—a sport in which it is near-impossible to insure the competitors outside of the Lloyd’s of London policies exploited by the likes of Curt Hennig—so few wrestlers have.

Yes, wrestling is fake. Yes, the stakes are comparatively low. Working together to make this extraordinarily unsafe spectacle palatable to viewers, highly skilled wrestlers still put their well-being on the line every time they enter the ring. And even in a sport defined by outsize violence, nothing is more out of place than actual physical catastrophe. We tune in for the expected surprises and spectacle, but not for unexpected and inexplicable tragedy. A heart attack, truly the “unknown unknown” of wrestling finishes, will always break kayfabe. Fans—and opponents and partners and referees—are left flailing, confused, paralyzed by the question of what happens next. Yet history and tradition tell us that the show, and the sport, must go on.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter @MoustacheClubUS and read more of his work at www.oliverbateman.com.