Ultimate Warriors: The Science Behind Ranking ‘Super Smash Bros.’ Characters

It can be tough work figuring out who the best fighters are in a game with 76 choices. Luckily, the pros have devised systems that even amateurs can sometimes benefit from.

Last week, Nintendo’s best-selling brawler, Super Smash Bros. Ultimate, received its 3.0 update, which, among other features, granted players the power to do battle between beloved video game characters atop giant genitalia. Those who were willing to fork over $5.99 also gained access to a new challenger: Joker, the protagonist of PlayStation RPG Persona 5. The addition of Joker, the game’s second downloadable character and the first of five paid characters coming to the game by February of next year, brought the total number of playable characters in the Switch title to an extraordinary 76.

Joker’s arrival also made Ethan Sternke’s task a little tougher. Sternke, an Indianapolis web developer and Smash competitor who uses the handle “inktivate” on Twitter and Reddit, is one of the leading figures in the Smash community’s never-ending efforts to determine the relative strengths of the series’ combatants, which are growing more numerous by the game and, in the age of downloadable content, by the year. “So many characters makes it as difficult as ever to get an adequate amount of experience to accurately place every character,” Sternke says.

The collective need to know how Smash’s many selectable characters stack up to each other dates back almost to the beginning of the 20-year-old series, which debuted in 1999 on the Nintendo 64 and gave rise to a rich competitive scene with the release of a sequel, Super Smash Bros. Melee, in 2001. As Anokh Palakurthi writes in The Book of Melee, his forthcoming book about the history of competitive Melee, “Endless discussions about Melee, both online and at events, usually came from one topic above all: Who were the game’s best characters?” As Palakurthi recounts, experienced players and tournament organizers at SmashBoards, the largest online Smash community, collaborated to produce the franchise’s first quasi-official tier list—a subjective ranking of character viability in high-level play—on October 8, 2002, about 10 months after the game came out in Japan and North America. The site has continued to present periodically updated tier lists for assorted Smash games ever since, although it has yet to release its first for Ultimate.

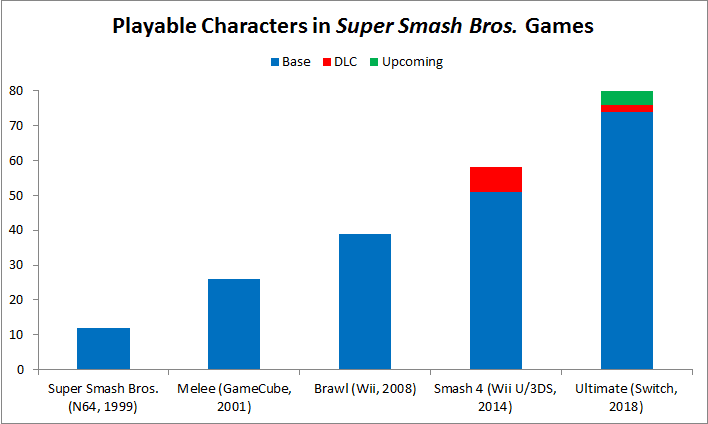

Melee featured 26 characters, more than double the original’s lineup of 12. Each subsequent sequel has further upped the ante in terms of character count. With a current tally of 76—including all 63 of the fighters featured across the previous four Smash games—Ultimate, which came out in December, is two downloadable additions away from tripling Melee’s complement of characters.

Tier lists aren’t unique to Smash; they’re also staples of other fighting games, as well as MOBAs like League of Legends and hero-based shooters like Overwatch. As Ultimate’s character count approaches 80, though, it’s testing the established boundaries of roster size for fighting games. Past installments in the Tekken, Mortal Kombat, and Marvel vs. Capcom series have had counts close to 60, but Ultimate’s is almost unsurpassed. (The 2007 game Dragon Ball Z: Budokai Tenkaichi 3, for one, checked in at 98, although the fourth and final entry in the series downsized to about 60.) That intimidating array of options makes it all the more imperative for players to impose some sort of order. Tier lists exist partly because people like reading and debating rankings, but they also help players navigate the increasingly crowded character-selection screen.

Over the years, the Smash community has developed two main approaches to tier lists, both of which are designed to take some of the subjectivity out of the tiers—or, at least, to embrace bigger samples and the wisdom of crowds. The first is an algorithmic solution based on tracking and recording tournament results and converting them into a ranking. The second involves averaging the publicized or polled preferences of pro players and other community notables to produce a combined tier list. Each approach has its merits, and neither is widely considered superior.

“The algorithm is very grounded in reality, as it crunches tournament data directly, but that also means it’s sensitive to character popularity,” says Smash statistician and analyst Andrew “PracticalTAS” Nestico. Some playable options in Ultimate are “echo fighters” that appear to be distinct characters but possess virtually identical movesets and abilities. If one echo is widely regarded as preferable to the other, the slightly inferior option will be underrepresented at tournaments even though its strength is almost the same. In other cases, one player who’s particularly adept with a less popular character may single-handedly raise that character’s rank. Nestico continues, “The average is more resistant to popularity-based problems, but is also more theoretical and less applicable to the average player.” Ultimate’s augmented roster increases the number of characters that place in each tier, but it doesn’t fundamentally alter the tier-list generation. “Really the two processes are the same as in past games, just with a longer list of characters,” Nestico says.

The algorithmic approach is favored by an Ultimate player and analyst who goes by “BarnardsLoop” (@LoopBarnard on Twitter). BarnardsLoop maintains a painstakingly collected record of results from 10 to 20 Ultimate events a week, not including online tournaments (which are subject to lag and disconnections, which can skew the stats). He spends roughly three hours every Monday aggregating and documenting character placements at the events, which he weights based on the prominence of the players who participate. “My motivation is simply that I enjoy it,” he says.

Sternke is the standard-bearer of the approach that mines the expressed preferences of pro players. “Since Ultimate only came out a few months ago, opinions on the tier list are extremely varied and debates on character strength are frequent and extended,” he says. “Since there hasn’t been any official tier list released yet, I thought I’d take it upon myself to average together all the pros’ tier lists I could find to fill that gap for now.”

Sternke also spends a few hours a week on his hobby, scouring Twitter, YouTube, and other sources for published pro tiers. He typically tracks about 20 players, and he includes any individual tiers from the past 50 days in his combined calculations, which yielded the following tier list as of early this month.

In Sternke’s last monthly update, three characters (Greninja, Zero Suit Samus, and Wario) jumped up a tier. As time passes and the tier lists get a little less volatile, Sternke says, he plans to increase that 50-day cutoff to incorporate older opinions. “The pace of change is definitely slowing down … but I think there’s still a lot of room for characters to grow, especially ones with more complicated techniques that haven’t really been explored yet.”

In early May, Ultimate will celebrate its six-month anniversary. While some single-player or less popular multiplayer games would have faded from view by this point, Ultimate is still in the early stages of a Smash title’s life cycle. Even though Melee is almost 18 years old, it remains a regular presence at tournaments, and its metagame—the competitive environment that arises from the set of strategies and tactics deemed most effective—continues to evolve. That’s particularly impressive given that the GameCube lacked built-in network capabilities and the capacity to patch the game, which means that Melee hasn’t changed except in the way people play it. Thanks to the experts’ innovations, Melee has churned through 12 “official” tier lists.

Sometimes a single high-profile victory can reveal a character’s unsuspected strength; when competitive Smash player ChuDat, who mains Ice Climbers, defeated Isai (then one of the world’s top-ranked players) at a tournament in 2004, it forced the community to reevaluate Ice Climbers as a viable high-level character. Even a decade later, Melee tiers could still be upended, as Japanese Smash player aMSa (now the world’s ninth-ranked Melee player) showed by enjoying unprecedented success with Yoshi. “Yoshi was not thought to be a viable tournament character until aMSa started making waves in the scene around 2014,” Sternke says. “He had mastered a lot of Yoshi-specific techniques like double jump canceling and parrying, which hadn’t been fully explored or utilized to their full potential by anyone else at the time. After scoring some huge upsets on some of the best players in the world, Yoshi made a huge jump in the tier list and is now considered much more viable than before.”

For Ultimate, some such surprises still lie ahead; today’s tier lists are only snapshots of the community’s current understanding, the best available sources in the absence of any definitive ranking derived from hard-coded character traits like speed, mobility, and damage-dealing. “Underlying attributes like frame data and hitboxes are important and useful, but there are far too many of those variables to make an accurate assessment of a character’s strength solely based on that data,” Sternke says.

There’s no real rivalry between the most prominent purveyors of the two types of tiers. BarnardsLoop and Sternke acknowledge the value of each other’s approaches, and BarnardsLoop notes that their tiers should converge over time, as tournament results shape players’ opinions. At the extremes, they already resemble each other. “The level of agreement you see in the two lists is pretty representative: rough agreement at the top, chaos in the middle, rough agreement at the bottom,” Nestico says. Five of the six top characters on Sternke’s list—including an echo fighter—also appear in the top five on BarnardsLoop’s list, and the bottom five on the former also appear in the bottom 11 on the latter.

There are some sources of significant disagreement. Xenoblade character Shulk, for instance, ranks 14th on Sternke’s list but is tied for 36th on BarnardsLoop’s. “Some say this is because he is a ‘high skill ceiling’ character with a lot of potential, and he won’t get the tournament results he could until players master all of his advanced techniques,” Sternke says. “Others say the tournament results speak for themselves, and he just isn’t very good despite his apparent potential.” Ness from Earthbound shows the opposite pattern, ranking 27th on Shernke’s list and 12th on BarnardsLoop’s; maybe his weaknesses just aren’t being exploited yet in tournament play, or maybe he’s better than the pros believe.

Both analysts agree on one crucial conclusion: Ultimate is exceedingly well balanced compared with at least the last two Smash titles, Brawl (2008) and Smash 4 (2014), boasting a multitude of characters that can hold their own in high-level play. “Most people right now view the game as pretty balanced, and it’s factually more so in terms of character diversity than Brawl/Smash 4 were at this point, which is good, considering those games were divisive not only for their mechanics but also because they had severe balancing issues,” BarnardsLoop says. “Ultimate right now in terms of character balance is about where Smash 4 was in mid-2016 after it balanced its initial top tiers … and Ultimate has the additional benefit of being viewed more positively since it’s faster and rewards more aggressive play.”

In Brawl’s case, Meta Knight was considered so overpowered that the character was sometimes banned from competitive play. In Smash 4, Sternke says, players were “pretty sure the best character in the game was Bayonetta or Cloud.” But in Ultimate, he adds, “people still aren’t sure, and it could be any of six to eight characters depending on who you ask (Peach/Daisy, Pichu, Snake, Wolf, Lucina, Olimar, etc.). … With the game being so balanced, it can feel like every character is viable at times!”

Sternke attributes Ultimate’s balance to two decades of development experience. “I think Nintendo has just gotten better at balancing the games over time,” he says. “The ability to patch things after release helps a lot too.” Neither of the game’s first two patches caused a notable shift in the meta, but it’s too soon to say what effects this week’s patch—which included three tweaks that applied to all characters and 163 additional adjustments distributed across 68 individual characters—might have. “Over time people will discover more things about the best characters and how to exploit the bad ones, but I think patching will generally keep the band small between the best and worst,” says Daniel “Tafokints” Lee, an analyst and competitive gamer who has served as the project manager for SSBMRank, an annual ordering of the top 100 Melee players.

When casual players pick up the controller, some characters that fare well in pro tournaments may be bad picks because they’re too tough to master, while other characters whose hidden weaknesses are exposed by the pros dominate because amateurs can’t counter their attacks. Even so, tier lists still serve some purpose for amateurs beyond their value as an intellectual exercise and their centrality to the spectator experience. “The high-level list will be filtered by low-level players to, ‘Which characters are high tier AND simple enough that I can pick them up?’” Nestico explains.

In light of the seemingly small gaps between Ultimate’s tiers, the difficulty of putting in enough time to get a feel for 70-something separate characters, and the possibility of patch-driven shakeups, the uncertainty surrounding the best way to win at Super Smash Bros. may be greater than it’s ever been before—and from the perspective of most players, that’s a plus. “I think it will be many years before we have a good idea of the ‘true’ tier list,” Sternke says. Assuming, that is, that the truth about tiers is even ascertainable.