How Chris Beard Built Texas Tech Into College Basketball’s Most Unlikely Juggernaut

The Red Raiders were long a Big 12 afterthought. Now they’re on the brink of a national title. The program’s meteoric rise is a credit to its transformative head coach—and a defense that’s redefining what’s possible in the modern era.Texas Tech head coach Chris Beard has probably coached basketball in every gymnasium between El Paso and Myrtle Beach that could double as a high school auditorium. He coached at community colleges in Kansas and Oklahoma; at Division III McMurry University in Abilene, Texas; at Division II Angelo State in San Angelo, Texas; and for a semipro team called the South Carolina Warriors in the comically disorganized modern reboot of the ABA. (The league has close to 100 teams, many of which are about to fold at any given moment.) After Beard bounced around the backwaters of basketball, his family wasn’t familiar with what to do when advancing to the biggest stage in college hoops. “The Beard family hasn’t been to too many Final Fours before,” the coach said after his Red Raiders beat top-seeded Gonzaga 75-69 in their Elite Eight matchup Saturday. “They were on their way to the locker room. I don’t think the girls understood we were about to cut the nets down.”

In just a few years, Beard has taken a largely irrelevant Texas Tech program and turned it into a powerhouse. The Red Raiders registered losing records in five of the six seasons before he was hired in 2016. It had been more than a decade since the program had a player picked in the NBA draft, and almost 20 years since the school produced its only first-round pick, Tony Battie. In Beard’s second year on the job, he lifted Texas Tech to its first Elite Eight and saw freshman Zhaire Smith selected 16th overall. Now Tech has made its first Final Four, and star Jarrett Culver is projected as a lottery pick. The Red Raiders have gotten here by embracing an aggressive and unique defensive scheme that baffles every opposing team.

Texas Tech has the best defense in college basketball this season, but leaving it at that undersells the team’s accomplishment. Since 2002, Ken Pomeroy has been tracking a stat called adjusted defensive efficiency, which estimates how many points a defense would allow against an average team over 100 possessions. The Red Raiders currently check in at 84.1, the lowest-ever figure in the 18 seasons of the data set.

If stats don’t do it for you, the way the Red Raiders made the Final Four should. In the Sweet 16, they took on Michigan—the second-ranked team in KenPom’s adjusted defensive efficiency metric. Michigan didn’t do much to slow Tech’s offense, as the Red Raiders scored 63 points on 62 possessions. Michigan, on the other hand, was completely shut down. The Wolverines went an abysmal 1-of-19 from 3 and committed 14 turnovers. “We heard from the different people that played [Texas Tech] during the year that you’re going to be amazed by how quick they are, how good they are at staying in front of people,” Michigan head coach John Beilein said after the Red Raiders routed his team 63-44. “They rally to the ball, which usually gives us open 3s, but you still can’t get open 3s.”

In the Elite Eight against Gonzaga—the team ranked no. 1 in adjusted offensive efficiency, according to KenPom—Tech limited the Bulldogs to under a point per possession. That marked just the second time all season that the Zags were contained to this extent. “We talked about it quite a lot in meetings and showed it on film, but it’s something you have to experience,” Gonzaga head coach Mark Few said of the Red Raiders defense in the moments after his team’s season had ended.

I can’t imagine a better way for a team to prove that it has the best defense in its sport than by dominating the team with the no. 2 defense and then downing the team with the no. 1 offense. And Tech’s defense is legitimately thrilling to watch. It’s not a quirky zone that waits out opposing offenses. It’s an attacking unit that operates at 100 miles per hour for 40 minutes, a breathtaking approach that looks exhausting to execute—and even more exhausting to play against. In the era of the 3-point shot, it’s time to find out whether defense really can win championships.

Texas Tech is a program filled with meteoric rises. Let’s start with Beard.

In 2015 the University of Arkansas–Little Rock took a chance on Beard, giving him his first Division I coaching job. The year before, the Trojans had finished 8-12 in the Sun Belt and ranked 288th in adjusted defensive efficiency. In Beard’s lone season in charge of the Trojans, they were 33rd in adjusted defense—the largest year-over-year jump in the history of KenPom—and went 30-5, making the NCAA tournament and upsetting fifth-seeded Purdue 85-83 in double overtime. UNLV hired Beard in the wake of that impressive turnaround, but the Texas Tech job came open three weeks later, presenting Beard with the opportunity to return to the school where he’d served as an assistant earlier in his career. He ditched UNLV—awkward, but understandable—and then proved that his performance at Little Rock wasn’t some small-league fluke.

Or take the evolution of Jarrett Culver. Three years ago, the forward was the 312th-ranked recruit in his class, according to the 247Sports composite rankings. Despite being a Lubbock native whose brother won an NCAA high jump title for the Red Raiders, Culver wasn’t being targeted by Texas Tech while Tubby Smith was the men’s basketball head coach. Beard took over and made Culver a priority. Now the sophomore is averaging 18.9 points and 6.4 rebounds per game and is sought after by scouts across the NBA.

Maybe Beard is lucky that an elite NBA prospect just happened to be balling unnoticed in his new program’s backyard. Or maybe molding little-known Texans into NBA players is simply Beard’s thing. After all, Zhaire Smith was once a mid-tier three-star prospect too; he spent just one season playing for Beard—averaging 11.3 points on 55.6 percent shooting—before going to the Philadelphia 76ers on draft night.

This is a roster of come-ups. Matt Mooney began his career at Air Force and hated it, transferring to South Dakota before winding up on the Red Raiders. Tariq Owens averaged 1.2 points at Tennessee in 2014-15 before transferring to St. John’s and later to the Red Raiders. Texas Tech has just one senior who has spent his entire collegiate career in Lubbock (Norense Odiase, who was originally signed by Tubby Smith) and just one player who was labeled a top-50 recruit coming out of high school (Brandone Francis, who averaged 2.0 points at Florida his freshman year before transferring to Texas Tech). Beard has shaped this group into a Final Four team and helped many of his players redefine their potential in the process.

Perhaps the most impressive transformation of all: the way Beard has made each of these players into quality defenders, regardless of whether they had strong defensive backgrounds. “I didn’t even play defense in high school,” freshman guard Kyler Edwards said. (When I told Beard about Edwards’s comment, he chuckled: “I hope somebody quotes that if he really said that. I need video evidence. I could use that.”)

Edwards isn’t alone. There’s not a college roster in America composed of guys who locked in at the defensive end in high school. Yet Beard has gotten his team to care, and that may have something to do with what Texas Tech calls the Kill Drill. “Oooooooh, it’s tough times in the Kill Drill,” Culver said.

The premise of the Kill Drill is simple: There are five guys on defense, and they have to play without substitutions for 90 seconds or three defensive possessions without giving up a basket. If the opposing team scores, the clock starts over. But it’s tougher than not allowing points. “It’s not really three stops,” Mooney said. “It’s three stops in Coach Adams’s eyes.”

Coach Adams is Mark Adams, who serves as a sort of defensive coordinator for the Red Raiders. Adams spent 30 years as a head coach in the Division II, NAIA, and junior college ranks before joining Beard’s staff at Little Rock in 2016. (His greatest accomplishment: winning the 2010 juco national championship at Howard College, a team led by future NBA player Jae Crowder.) Beard and his players are quick to acknowledge that Adams is responsible for the team’s defensive prowess. “I think he’s the best coach in college basketball that people don’t really know who he is,” Beard said.

In the Kill Drill, Adams considers any defensive breakdown cause to restart the clock. “If you’re not talking, he says ‘OK, start it over,’” Mooney said. “If I’m not in my stance, start it over. Tariq got the rebound, but he didn’t box out. Start it over.” Francis recalls a time during a full-court Kill Drill when his team kept the opponent from scoring for 88 seconds. “They took a shot at two [seconds], glassed it, went in. I’m like come on, man!” Francis said. “You can be in the pit for like 40 minutes. They have no mercy. That’s the time when you think, ‘Why?’”

There’s a bit of flawed logic in the Kill Drill—it punishes both bad defense lucky enough to get good results and good defense unfortunate enough to get bad results. Yet it’s forged a group of players who want to get defensive stops more than anything in the world and who are on the doorstep of a stunning national title because of it.

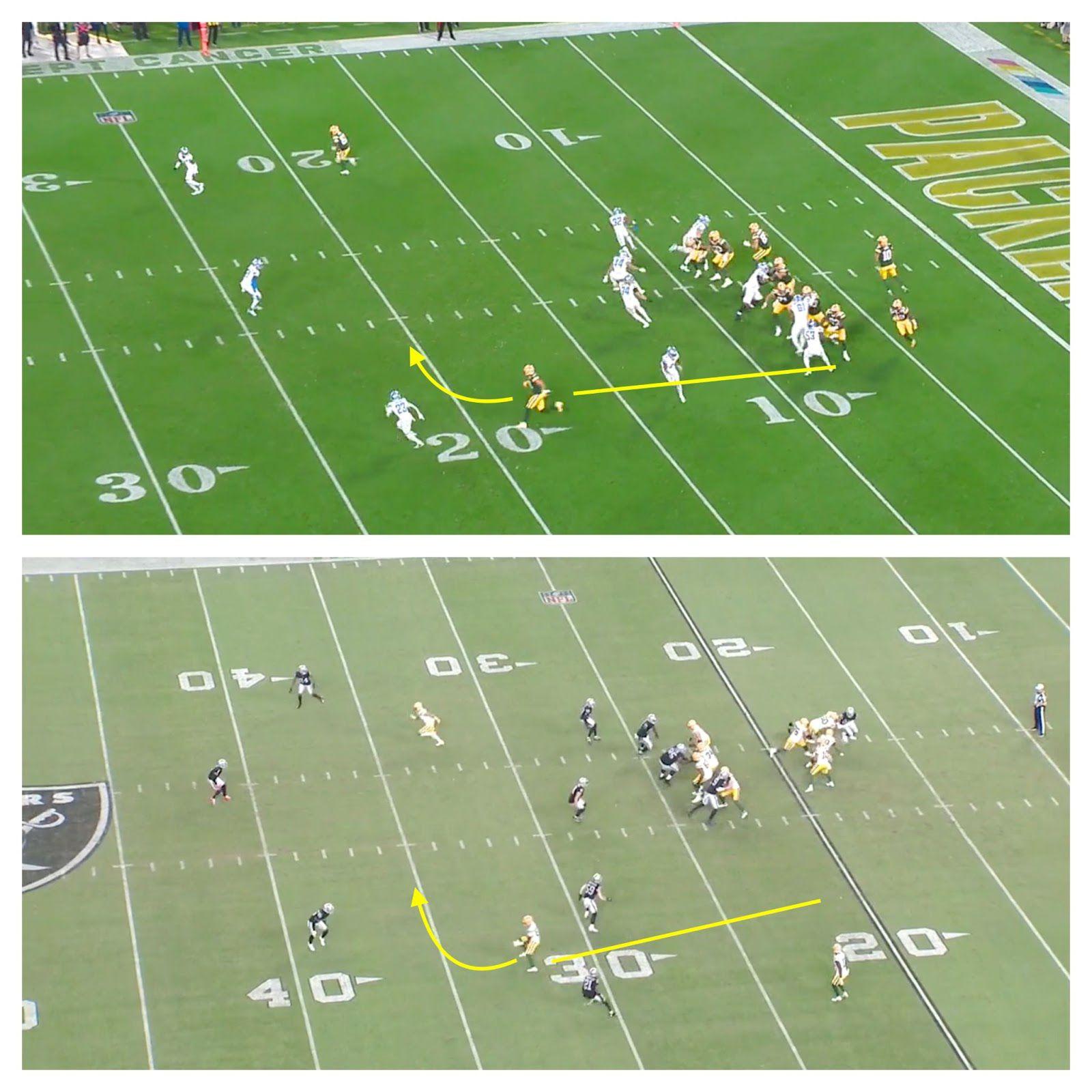

The Red Raiders’ defensive style seems like it shouldn’t succeed in an era when the 3-point shot is king. Texas Tech’s primary goal is defending the middle of the floor. Not the basket, not the 3-point arc. The middle. Just look at where Tech’s on-ball defenders typically position themselves when guarding a player beyond the arc.

Instead of standing between their man and the basket, Tech’s defenders stand between their assignment and the middle of the court, with their feet essentially parallel to the sideline. This might look like it makes it easy for opponents to drive toward the baseline … and it does. That’s fine. Because that’s precisely what Texas Tech wants. If an opposing player takes what he’s being given, then a wall of Red Raiders help defense will come crashing down upon him. Tech’s aggressive on-ball defense forces opponents into driving baseline, and its aggressive help defense forces them into making bad decisions. (I highly recommend this breakdown of Texas Tech’s defense for a full explanation of how the Red Raiders handle different scenarios, and how ineffective various methods of attacking the scheme are.)

For those familiar with college sports, it might seem funny seeing Texas Tech operate this way. The most notable thing about Red Raiders’ athletics in the 21st century is the football team’s steadfast dedication to Air Raid offense. Texas Tech has pushed the envelope of what is possible in football, with head coaches Mike Leach and Kliff Kingsbury crafting revolutionary offensive schemes. They’ve had little sustained success, though, as the team’s poor defenses and talent disadvantages have kept the Red Raiders from even making a conference championship game. (Kingsbury posted a losing record at Tech before he was fired in December. He was instantly coveted by NFL teams for his offensive acumen, and in January was hired as the head coach of the Arizona Cardinals.)

Now the basketball team has instituted a revolutionary defensive scheme—the Air Raid of basketball defense, if such a thing is possible. The difference is that it has immediately vaulted Tech into the upper echelon of the sport, as the Red Raiders won this season’s Big 12 regular-season title (the first time since 2004 that Kansas didn’t win it) and now made the Final Four.

Generally, I prefer great offense to great defense. Great offenses are zany and imperfect, seeking to push the limits of what’s possible; great defenses are built on discipline and control, trying to limit what an opponent can achieve. But I find the Tech defense fascinating. It doesn’t react. It attacks.

Beard emerged from the lower levels of the sport to build a program that was long an afterthought into a contender and to develop players who were once off the radar into prized pro prospects. It’s a ridiculous rise, and it’s not over yet. Maybe next Monday Beard’s family will know to stay on the court for the net-cutting.