Rebel: Power and Protest at Ole Miss

On February 23, eight men’s basketball players knelt during the national anthem to denounce a Confederate rally in Oxford. For many students, their protest was a continuation of a long battle to rid the campus of its symbols of a harmful past.On February 23, Devontae Shuler, a sophomore guard on the University of Mississippi men’s basketball team, stepped onto the court for warm-ups before a home game against the University of Georgia. Shortly before tip-off, he lined up alongside his teammates and coaches, standing shoulder to shoulder, as both teams and the more than 7,000 people in attendance prepared for “The Star-Spangled Banner.” As the music began to play over the loudspeaker, Shuler breathed deeply, bobbed his head up and down, and dropped to one knee. By the time the song finished, seven of his teammates had joined him.

“I felt like I needed to stand up for my rights for righteousness sake,” Shuler told The New York Times. “My emotions were just for the students. I didn’t want anything to happen with us playing that game while the protest was going on. I felt like I couldn’t pass that moment by without making a difference.”

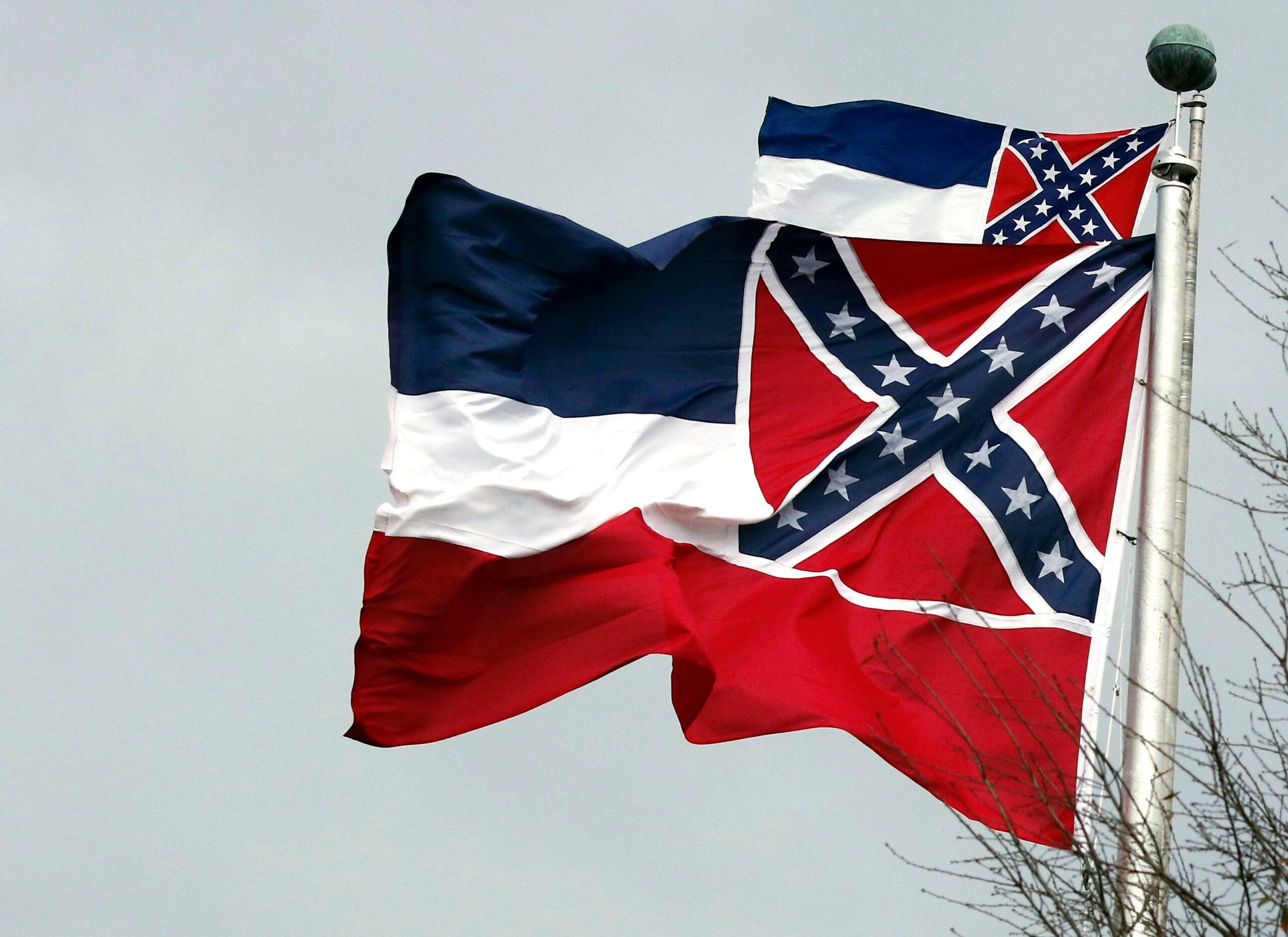

Not far from the basketball arena, members of two Confederate groups marched through Oxford’s town square, chanting “God bless Dixie” and “Heritage, not hate,” protesting attempts to remove Confederate monuments and symbols from the campus. Portions of the student body have long lobbied the university to rid itself of such iconography—that Saturday, people came to Oxford to denounce those efforts.

Some students said they could feel the tension simmering on campus in the days leading up to the rally. A member of one of the groups, Confederate 901, posted a video on Facebook in which he said, “These little snot-nosed motherfuckers don’t know the first thing about nothin’! But they fixin’ to get educated!” University officials advised students to stay away from the rally, and some faculty members canceled classes the day before in response to students’ unease about the march.

Athletic director Ross Bjork arrived at the arena 30 minutes before Saturday’s game, greeting fans and boosters as the team warmed up. He hadn’t yet made it to his seat when he saw the players kneel. He said he had received text messages from student-athletes expressing concern about the rally, but he and head basketball coach Kermit Davis had no prior knowledge of the players’ decision to protest.

“Are they OK? Is it in relation to what’s happening on campus?” Bjork remembers thinking. He hurried to a private room to confer with athletic department staffers. “Let’s get ready for postgame,” he said. “We are going to have to talk about this.”

The image of the players taking a knee was striking and not often seen in major college sports, where few athletes have followed the example of Colin Kaepernick, the former 49ers quarterback, who first knelt during the national anthem in 2016. He hasn’t played in the NFL since that season ended. In October 2017, he filed a grievance against the league, accusing owners of collusion; he reached a settlement with the league last month for an undisclosed amount. While it is rare to see student-athletes take such action, there is a long tradition of students harnessing the power of protest at the University of Mississippi, a continuation of a decadeslong struggle to compel the institution to fully divest from its past. What the players did that Saturday afternoon was not only a singular revolt against a rally that sought to defend the Confederate symbols woven into the fabric of their campus. It was also a flash point in a direct reckoning over the racism and violence that has swept through the university since its inception.

After the game, Breein Tyree, a junior guard and the team’s leading scorer, told reporters, “We’re just tired of these hate groups coming to our school and portraying our campus like it’s our actual university that has these hate groups in our school.”

Bjork said the emails he received were mostly negative in the “24 to 36 hours” after the protest, but that the players had the full support of the university. He acknowledged that the events of the weekend were a reminder of how much progress still needs to be made at the university.

“I don’t think the conversation about race and the university will go away,” Bjork said. “I think we need to embrace the fact that we can learn from this so it doesn’t happen again.”

I met Anne Twitty, a history professor at the university who researches antebellum America and slavery, on the steps of the Lyceum, the university’s 171-year-old administration building. Bullet holes from the integration riots in 1962 are still visible on the columns, though they’ve been glossed over with a crisp white paint. Twitty has agreed to be my tour guide. She wants to show me the things the university continues to hide.

The most haunting example is the Croft Building. Built in 1853, it served as a hospital during the Civil War. If you look closely, you can see what Twitty said are the imprints of black children’s fingers etched into the bricks, evidence of the children who constructed the building. Three fingerprints appear underneath a window, pressed into the brick.

“These [monuments] are a direct result of this. They show that black people here are accepted only in servile roles,” said Twitty. “You can no longer be our slaves, but you can be our servants. That is the only condition where your presence is welcome. ... It is designed to send a message that white supremacy is the order of the day. The university is not a neutral bystander. This didn’t happen to us. We did this.”

The history is built into the campus: Antebellum-style homes with ivory columns line Sorority Row; the university chapel sits on a street that, until 2014, was named Confederate Drive; a statue of a Confederate soldier keeps watch at one end of the Grove, a 10-acre plot of land in the center of campus that hosts the Rebels’ famed football tailgates; a second statue, dedicated to unnamed Confederate soldiers, sits in the town square.

“I’ve never lived in a place that’s so in your face with its neoconfederate ideologies,” said Kiese Laymon, an author and professor in the Department of English. “It’s the hardest place I’ve ever lived. To wake up and go to sleep.”

The University of Mississippi became the state’s first public institution of higher learning in February 1848. “Ole Miss,” as the university is colloquially known, derives from the phrase “Ol Missus.” In his 1999 book, The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, historian David G. Sansing describes the term as “a title domestic slaves in the Old South used to distinguish the mistress of the plantation house from the young misses of the family.”

The university is not a neutral bystander. This didn’t happen to us. We did this.Professor Anne Twitty

Jessica Wilkerson, a professor of history and Southern studies at the university, said Oxford is a symbol for the groups who participated in the rally.

“There are two [Confederate] monuments in Oxford, pointing to each other, that you can walk to,” said Wilkerson. “The whole campus is like a monument to white supremacy.”

In 1962, James Meredith, a 29-year-old black Air Force veteran, successfully sued the university after, in defiance of the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka, it denied him admission twice. His legal victory set off violent mobs throughout Oxford. On state television, Ross Barnett, the Democratic governor, exclaimed that “no school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your governor” after the state legislature tried to have Meredith jailed on trumped-up voter-fraud charges.

“I was going after the enemy’s most sacred and revered stronghold,” Meredith wrote in his 2012 book A Mission From God. “My application to Ole Miss had little to do with ‘integration’ but was made to enjoy the rights of citizenship, and by doing that, to put a symbolic bullet in the head of the beast of white supremacy.”

There’s a long list of hard-fought gains made by black students at the university. A black player did not play for its football team until 1972, making it the last team in the SEC to integrate; in 1982, the school’s first black cheerleader said he wouldn’t run onto the football field holding a Confederate flag; when Fraternity Row integrated in 1988, a house for Phi Beta Sigma, a black fraternity, was burned. The university stopped using the Confederate flag in an official capacity in 1983; the school took measures to remove it from the football stadium in 1997. It banished the mascot Colonel Reb in 2003, removed the state flag from campus in 2015, and banned the playing of the song “Dixie” at sporting events in 2016. Charles Ross, the director of the African American studies department, has taught at the university since 1996. He said these changes have often happened via the will of black students.

“Many African American students have come to this campus and have come with the mind-set of knowing what the institution’s reputation is,” said Ross. “Your aunt, your mother, your grandmother, everyone says, ‘Why are you going there? You know you can’t change those white people.’ You understand that it has had the most turbulent racial history maybe of any institution in the United States.”

The basketball players’ protest reignited a conversation that has been happening on campus and in classrooms, a conversation they publicly lent their voices to in order to shape the future of the campus. It marks a breakthrough for athletes at the university but also for the student body, whose efforts influenced their protest.

“We have movement, and the reason we do is because many young African Americans have decided that this is their school, they are citizens, some grew up here,” said Ross. “We can be political. We can apply pressure. We don’t need to simply come here and have a certain amount of patience and acceptance of the way things have been.”

But these incidents come at a cost, especially when students feel that their cries go unheard. Some black students say they argue with white students in classrooms about the right to protest, and some black faculty members say they avoid living in Oxford or wearing the university’s colors. What exists is generational fatigue.

“I know that feeling. And I lost that battle in my time at the university. I never felt safe. ... I got my degree and got the fuck out,” said Dominique Scott, a 2017 alumna who led the campaign to have the state flag removed from campus in 2015. “And I don’t come back. I was exhausted. Bone-marrow tired. And the university beat me. The university won. White supremacy won. It did exactly what it was supposed to do to women like me. It chewed me up and spit me out. And I ran from that place. But if a black woman at the University of Mississippi ever asked me what I’d do to feel safe, I’d say leave.”

The Fulton Chapel has been a staging ground for campus dissent since integration. In February 1970, black student activists were arrested there after interrupting a concert and raising black power salutes. On February 26, three days after the Confederate rally, it is the site of a forum between administrators and around 50 students. They’ve gathered to have a transparent conversation about the events on campus that weekend. According to some students in attendance, it is too little, too late: Where was the concern before these groups marched on Oxford?

“Nothing I say will convince folks that I do care, but I do,” said Katrina Caldwell, vice chancellor for diversity and community engagement at the university, as she steps to the microphone. “We see this as action,” she said of the forum. “But nothing is going to convince you that’s the case until action happens.”

The students who take the microphone decry not only the toxic environment they say persists on campus, but also what they perceive as the university’s lack of action and attention to their concerns.

“This isn’t the 1960s,” said Arielle Hudson, the 21-year-old vice president of the Black Student Union. “I’m not James Meredith. I shouldn’t have to walk around campus with my head down. These people shouldn’t be on our campuses.”

Some students gathered in the chapel’s pews said they have been to forums like these in the past, and they’ve listened as university officials promise change, only to leave disappointed. The statues for Confederate leaders and the school buildings named after dead slave owners have not been removed or renamed.

It’s the hardest place I’ve ever lived. To wake up and go to sleep.Professor Kiese Laymon

“How many sleepless nights and missed assignments do I have to go through before something is done?” sophomore Mya King asked the crowd. “We want to go to school and enjoy ourselves. We don’t want to have to fight for equality every single day.”

The emotion is amplified when JoJo Brown, a 21-year-old student ambassador who gives campus tours to prospective students, takes the microphone. “Coming here—” her voice cracks. “I’m sorry.” She begins crying as she speaks.

“As an African American woman, everywhere I go, someone said, ‘Why would you go there? It’s racist. They don’t want you there.’ We catching that heat! People attacking us. All of that! It’s everywhere! And what do I say to the prospective students that wanna come here? ‘They give you a great education’?” She chuckles sarcastically. “Why would I want a great education somewhere it’s not safe? Why?!” She starts slamming her hands together.

“I’m tired of backtracking! Every time we get ahead, we get knocked back. I’m sick of it! I’m tired of these symbols on campus. I’m tired of the names on the buildings. It is so much work that needs to be done. And I don’t know how much more of this I can handle. I was literally considering transferring after what we’ve encountered this year. Students don’t even wanna stay here … because of the baggage, because we refuse to give up the symbols on campus that still represent that history that we are trying to put under the rug like they not there.”

The conversation continued at another campus event later in the evening. Eleven student groups were joined by former athletes in a ballroom at the student union to have a faith-based discussion about racism on campus. Among those in attendance were Coolidge Ball, a former basketball player and the university’s first black athlete; Jason Cook, a pastor and former fullback on the football team; and Keith Carter, a former All-American on the basketball team. The event had been planned for two weeks, but when Cook addressed the crowd, he acknowledged the events of the past weekend.

“People view kneeling as a hostile event rather than an expression of the last 400 years,” said Cook, according to The Daily Mississippian. “Persevere through the microaggression. Persevere through when we feel attacked. Persevere through the white guilt. You can’t quit.”

On Wednesday, February 27, the basketball team returned to the Pavilion to play Tennessee, its first game since the protest. Fans wore shirts imprinted with slogans like “Rebel Rags” and “Rebs or Go Home,” while “My Dawg” by Lil Baby blared through the loudspeakers. The university’s band, the Pride of the South, played along the baseline as an American flag swayed above Craddock Court. Dancers waved “R-E-B-E-L-S” flags around the court. It’s the same iconography these athletes protested against. The very imagery that so many are calling to be removed from buildings and statues is visible in plain sight.

After the game, players deflected questions about the protest. The campus and administration stood together against hate, they said. They would not repeat their actions.

“We aren’t worrying about that anymore,” said Bruce Stevens, a senior forward. “It’s in the rearview mirror and we’re just thinking about basketball.”

On Friday, the basketball team will make its first NCAA tournament appearance in four years. On March 5, student leadership unanimously approved a resolution recommending the relocation of the Confederate statue from the edge of the Grove. “I don’t think it’s any coincidence that this bill (resolution) is coming on the heels of [the protest],” Associated Student Body vice president Walker Abel told The Daily Mississippian. Interim chancellor Larry Sparks issued a statement Thursday saying the university agreed with the resolution and that “the monument should be relocated to a more suitable location.” He said the university is consulting with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History to secure the necessary approvals but that the process “will require some time.”

We can be political. We can apply pressure. We don’t need to simply come here and have a certain amount of patience and acceptance of the way things have been.Charles Ross, director of UMiss African American studies department

The power of protest remains a driver of change at the university. That February weekend in Oxford showed how it happens, even though there is still work to be done, even though the past can never be erased.

“A lot has to change,” Twitty said a week before the resolution passed. “There’s the really obvious things. The Confederate monument has to come down. But it’s not ever enough … sometimes this causes a lot of heartsick. It’s like picking a scab. You can get rid of it. But in some measures, there’s still going to be a scar. It never heals.”

An earlier version of this piece included a photo of a building that was incorrectly identified.