Wilt Chamberlain wasn’t just a scoring champion. He topped the rebounding leaderboards, too, and took the league’s crown in 11 of his 14 seasons, often averaging by himself what an entire frontcourt does in the modern NBA. But the 42 boards he gobbled up 50 years ago Thursday in an overtime win over the Boston Celtics represent his most relevant rebounding feat viewed from today’s context.

Chamberlain’s besting of Bill Russell on the boards wasn’t just the most recent 40-rebound game; it was the last. As in, final; complete; etched, essentially, with chisel in stone.

The modern game has caused records to fall and statistical outliers to erupt at the same frenetic pace as its games are played. Russell Westbrook will average a triple-double over a full season for the third time in a row. James Harden can’t stop climbing historical leaderboards. Klay Thompson set a record by sinking 14 3s in a game, just two years after teammate Steph Curry set the record with 13. Anthony Davis and Jusuf Nurkic posted quintuple-nickels (five each of points, rebounds, assists, steals, and blocks) just six weeks apart. Two of the 10 records Bill Simmons detailed in his Book of Basketball as the most unbreakable have fallen in the past four years.

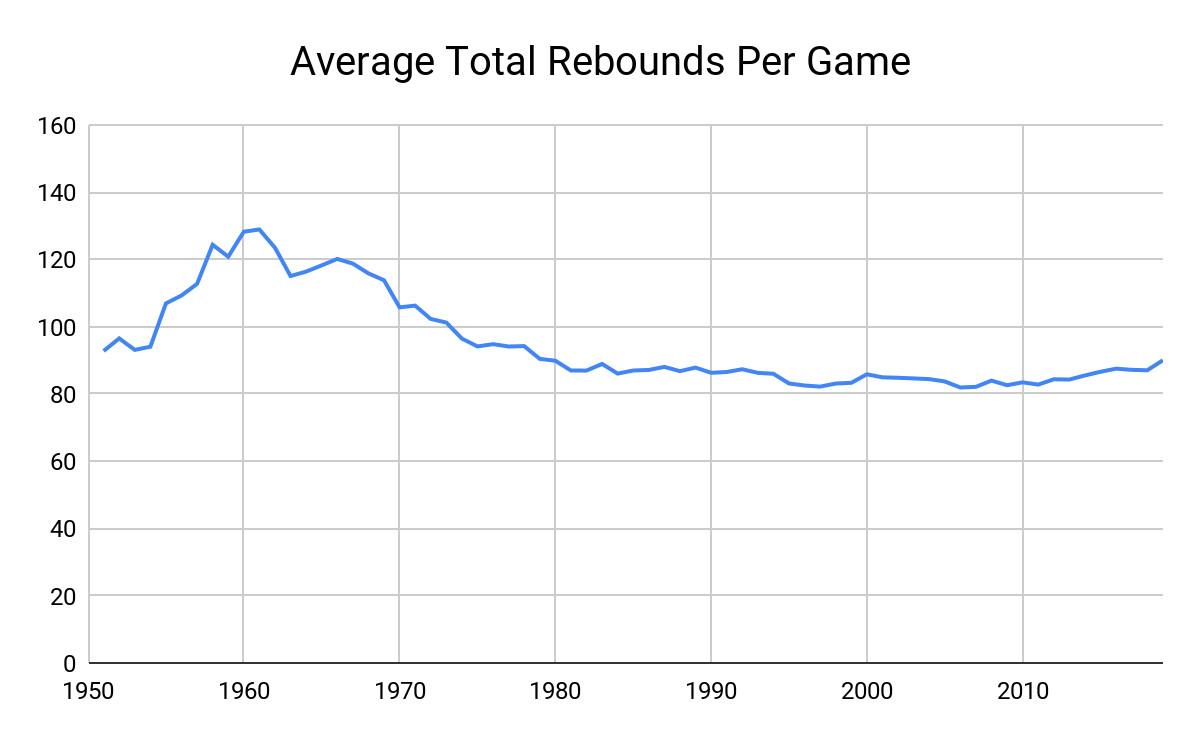

But rebounds stand distinct, their records untouched, even from a distance, by modern man. The single-game record is 55, courtesy of Wilt in November 1960, which is so absurd from a modern vantage that it might as well be a million. There’s a reason Joel Embiid told NBA Desktop that he considers Chamberlain the GOAT because of all his records. No team has averaged 55 rebounds per game since 1972-73—which was Chamberlain’s last season. No team has averaged even 50 rebounds per game since 1977-78.

Wilt’s rebounding anomalies extend beyond just that record. For instance, according to Basketball-Reference’s records, Chamberlain and Russell combined for 22 of the 24 40-rebound games in NBA history, as well as the top 18 single-season rebounding averages. Chamberlain tallied 25 separate 30-rebound games in his rookie season. That’s more than there have been total 30-rebound games from every NBA player combined since he retired.

Since then, Charles Oakley has the most single-game rebounds with 35 in 1988. Three decades later, even Oakley’s mark looks unattainable: Dwight Howard’s 30-board game last season was the league’s first since 2012 and just the third since 1996.

So why are rebounds seemingly immune to other sorts of statistical inflation? Let’s contrast Wilt’s situation with that of Andre Drummond, who’s averaged at least 13 rebounds per game every season since he was a rookie and led the league in three of the past four. If Drummond sought to claim the single-game rebounding record in 2019, three main factors would stand in his way.

Factor no. 1 that suggests Drummond would struggle to challenge Chamberlain’s total is that teams in 2019 don’t take enough shots. The league’s pace seems hectic this season, as teams attempt nearly 89 shots per game, the highest mark in 30 years. In 1960-61, when Chamberlain set the record, teams attempted ONE HUNDRED AND NINE shots per game.

To put that number in perspective, in the past decade, just four teams have taken 109 or more shots in a non-overtime game (and three of those four hit 109 exactly). In 1960-61, that was the average—which means that teams went higher than 109 shots half the time; the night Wilt tallied 55 boards, his team took 128 field goals and 41 free throws. As Simmons wrote in The Book of Basketball about the pace-inspired wonkiness of this era, “Compare the numbers from [then to now] again. Still impressed by Oscar’s triple-double or Wilt slapping up a 50-25 for the season? Sure … but not as much.”

So many more shots meant so many more rebounds, especially when combined with factor no. 2 in Wilt’s favor versus Drummond: Teams in 2019 don’t miss enough shots. In 1960-61, leaguewide field goal percentages had only just crossed 40 percent. All those extra shots often missed, and they often found their way into Chamberlain’s giant paws.

The difference in shooting percentage between 1961 and 2019 would lead to about 8-10 extra rebounds per night in a single game, even before accounting for the former season’s heightened pace. Accounting for pace yields a massive difference—about an extra 40 rebounds every game for teams in the 1960s to chase.

Yet even if pace rocketed back to 1960s levels, and even if shooting percentages regressed half a century, Drummond still wouldn’t challenge the record unless his coach were in on the scheme, too. That’s because of factor no. 3: Players in 2019 don’t collect enough minutes.

Coaches and front offices understand the importance of rest much better than they did a half-century ago. Monta Ellis in 2010-11 is the last player to exceed 40 minutes per game over the course of a season, and no big man has done so since Kevin Garnett in 2002-03. That’s a stark departure from more ancient NBA history, and from Wilt especially. Even more than his 50.4 points per game, Chamberlain’s most unbreakable single-season record might be his minutes-per-game mark: 48.5 in 1961-62. Yes, he averaged more than a regulation game. Think that one over.

More broadly, last season, the league’s top 10 rebounders averaged 32 minutes per game, the lowest on record. In Wilt’s heyday, that average regularly topped 40. So in addition to the advantage prior-generation players had because of their era’s pace, and in addition to the advantage prior-generation players had because of their era’s field goal inaccuracies, prior-generation players were also allowed to play more.

When Wilt or one of his rivals grabbed a bunch of boards in quick succession, they just kept going. Not so in 2019. As of the All-Star break, there had been 60 quarters in the past three seasons in which a player tallied 10 or more rebounds. Drummond himself has done it 11 times. Those aren’t trivial totals; they’re the precise pace needed to reach 40 boards in a game. But because of rest minutes, that kind of pace is simply unsustainable over a full game, or even just a half. Out of those 60 occasions, only one—for Howard in his 30-rebound game—yielded a 20-rebound half.

Ultimately, while Drummond might expect to be on the court for about 60 rebound opportunities in the average 2019 game, his half-century-ago predecessor would have expected to be on court for about 110. Wilt would have encountered even more, given his workload.

That disparity leads to the final piece of Wilt’s rebounding puzzle. The secret of Wilt’s extraordinary rebound totals is that compared to modern centers, he wasn’t actually an extraordinary rebounder. Or, at least he was extraordinary in a different way.

Because of the lack of comprehensive play-by-play data for most of Wilt’s career, we have exact rebounding percentages for only the final three seasons of his career. In those seasons, he grabbed 19.4 percent of available boards when he was on the floor. That’s a lofty number, but it didn’t lead the league during that span, and it would place him behind four active players on the career leaderboard in Drummond, DeAndre Jordan, Dwight Howard, and Kevin Love.

Maybe that tally isn’t fair to Chamberlain, given that it comprises the end of his career rather than his peak. Luckily, we can tinker with some available data from earlier in Wilt’s run. Let’s zoom in on the three-season stretch from 1960-61 to 1962-63, when he produced the best rebounding numbers of his career and also played in 99 percent of all possible minutes. In the 132 Warriors games in that span for which Basketball-Reference has rebounding data, Wilt’s rebounding percentage was 20 percent on the nose.

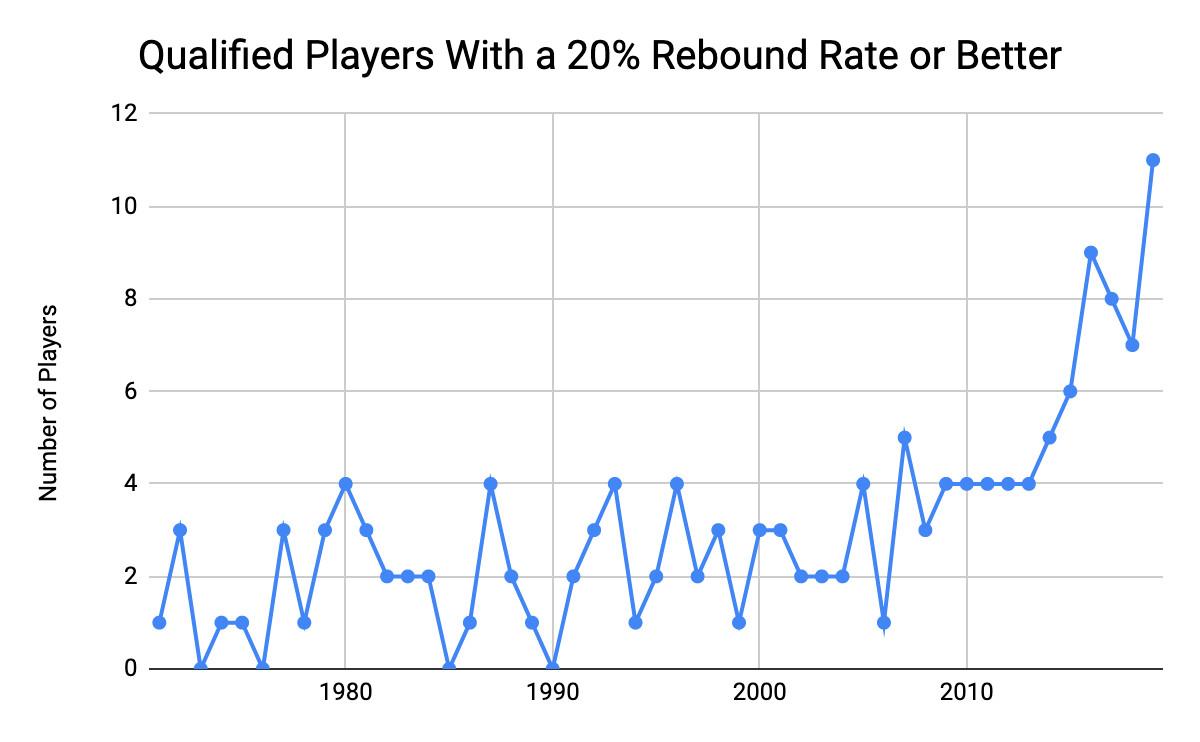

That’s good! But not historically so, or even particularly notable next to totals from this decade. In 2018-19, 11 qualifying players boast a higher mark, and that group includes Embiid, who lauds Wilt as superior to Michael Jordan specifically because of records like these. Maybe Embiid should call himself the greatest.

The irony of Wilt’s rebounding records is that more of today’s centers are collecting a higher percentage of rebounds than ever before. The five seasons with the most qualifying players with a rebounding percentage of 20 or better are the five most recent seasons, as many traditionally sized rebounders leave the court (or spread out on it) and yield more space for the few remaining close-to-the-basket bigs.

And that discrepancy carries single-game ramifications as well. Wilt collected 55 of 149 total rebounds in his record game. That’s 37 percent. Drummond hit that mark in a game this season. Jordan did it three times. Hassan Whiteside did it four. In Wilt’s final 40-rebound game—the one celebrating its 50th anniversary—his rebounding percentage was just 28 percent, as he benefited from playing all 53 minutes in a fast-paced overtime duel. That’s barely more than Drummond’s average now.

There are caveats, of course: Wilt’s rebounding percentages would have improved if he hadn’t had to pace himself for 48 minutes, and he would’ve grabbed even more rebounds had the court been dominated by guards and wings instead of fellow bigs who he had to fight for boards. This exercise is meant to gaze in awe at Wilt’s statistical hegemony, not conclude that he was Drummond or Whiteside with a heavier workload in a different era. At least his totals stand alone, a numerical testament to the unassailable mix of right player, right time, and right place.

Thanks to Mike Lynch of Basketball-Reference for research assistance.