Solange moves in no particular hurry, but make no mistake: She’s moving. Glacially, deliberately, and to modern rhythms, like chopped-and-screwed tai chi. “I grew up a little girl with dreams, dreams, dreams,” she sings on her trancelike new album, When I Get Home, and as she’s told it in interviews, so many of those early dreams were about cultivating an expressive artistry of the body: getting into Juilliard, dancing in the Houston Ballet, being Debbie Allen on Fame. But somewhere along the line, the pace of Solange’s life went into hyper speed—the velocity at which youthful dreams tend to evaporate in a blink. When she was 17, she married her childhood sweetheart and gave birth to a son later that year. This was 2004—the year after Dangerously in Love came out—so she was also clocking her older sister’s rise to becoming one of the most famous, and perhaps one of the fastest-moving, people on the planet. And so, for the moment, her own dreams were deferred.

In her own time, though, Solange became herself. After two relatively generic early albums that sought to brand her as another child of destiny, a then-26-year-old Solange released “Losing You,” a hypnotically hip 2012 collaboration with the producer-musician Dev Hynes. The song itself has an underlying tension: Solange’s vocal is melancholy and yearning (“Tell me the truth, boy, am I losing you for good?”) but there’s a party happening inside that beat. Sampled screams of revelry give the track a haunting, living energy. Like Robyn’s “Call Your Girlfriend” before it, “Losing You” is one of the millennium’s great odes to crying on the dance floor.

“Losing You” was accompanied by a striking, stylish video set in South Africa and directed by Melina Matsoukas, who would go on to helm Beyoncé’s iconic “Formation” clip and develop much of the look and feel of the elder Knowles’s groundbreaking visual albums. The “Losing You” video now feels like the seed of an aesthetic that both sisters would further refine in the coming years: a performer commanding the frame with a confident stillness; bold costuming; black people filmed with flair, dignity, and a palpable feeling of love. But what Solange had not yet tapped into on “Losing You” was her fearless sense of austerity—a force of vision that would soon become her superpower. At moments in the “Losing You” clip she still seems to be mugging for the camera, occasionally cracking into a charming smile.

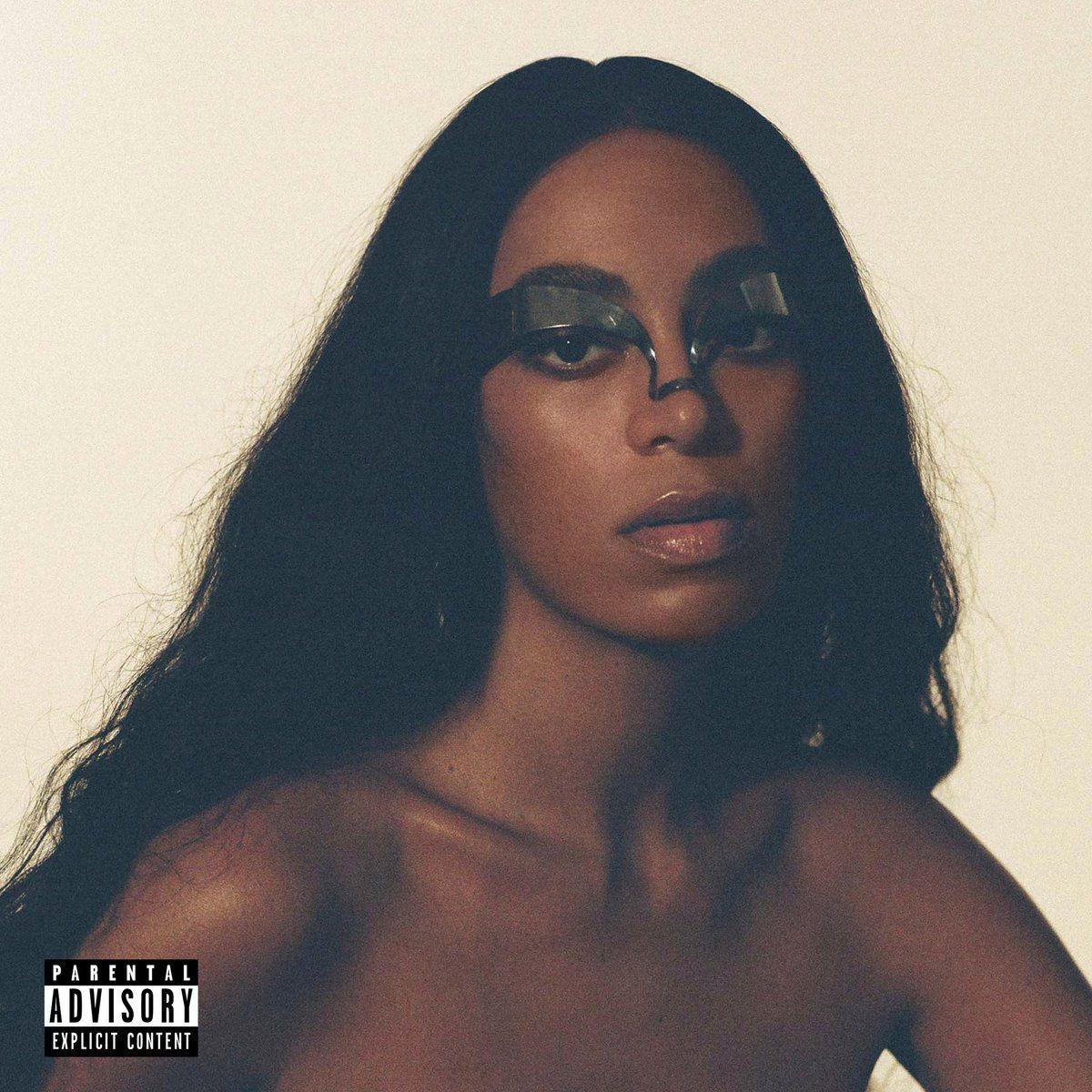

Contrast that with the cool, uncompromising gaze we see on the cover of A Seat at the Table, Solange’s 2016 masterpiece. “I wanted to nod to the Mona Lisa and the stateliness, the sternness that that image has,” she told her sister in an Interview magazine conversation. And did she ever. “I’m weary of the ways of the world,” Solange sang in the opening minutes of the record, which had the immaculate timing of arriving a month before the 2016 election, and in the middle of a never-ending season of unarmed black people being shot by police. Somehow, in such a troubled time, this record had the healing properties of a homeopathic salve. A Seat at the Table is, among many other things, a record about the power of setting boundaries and saying no: Three different songs begin with the word “don’t.” (“Don’t You Wait,” “Don’t Touch My Hair,” and, perhaps most searingly, “Don’t Wish Me Well.”) “Cranes in the Sky” is a profound catalog of the many things a person can do to avoid taking a good, hard look in the mirror. But as singular and even lonely as the record could sound, A Seat at the Table was ultimately a celebration of black community. Solange’s mother, father, and No Limit impresario Master P ably served as narrators, sharing the struggles of their pasts to ground the record in a shared history. “You got the right to be mad,” Solange sang on the slow, long-haul march “Mad,” “but when you carry it alone you’ll find it only getting in the way.” What a benevolent battlecry.

A Seat at the Table was decidedly earth-bound. The visuals for “Cranes in the Sky” (a collaboration with Solange’s husband, music video director Alan Ferguson) found Solange posed in front of dramatic, craggy landscapes, her bare feet in communion with the land. Its lyrical concerns, too, dealt directly with what was going on in the physical world in the year 2016: police brutality, cultural appropriation, and the difficult necessities of self-care. In the past few years, American life has, unfortunately, not changed much, and these problems have certainly not gotten any better, but Solange’s follow-up to Seat isn’t taking on the burden of saving the world. When I Get Home is a celestial, even psychedelic, enterprise, suggesting that a way to feel less weary of the ways of the world is to hop in a retro-Funkadelic spaceship and transcend it entirely. When they go low, Solange goes hiiiiigh.

The patchy fluidity of the 19-track, 39-minute When I Get Home reminds me of some recent records like Tierra Whack’s Whack World, Vince Staples’s FM!, and When I Get Home guest-producer Earl Sweatshirt’s Some Rap Songs: albums that seem not so much like listening to collections of clearly delineated and fully realized singles so much as channel-surfing through a restlessly innovative artist’s mind. “I saw things I imagined,” Solange chants on the opening track, repeating it enough times that it becomes an invocation—an assertion that we’re about to enter the realm of the subconscious. And so intros melt into outros, obscure samples cut in and out like weak radio frequencies, and songs rarely linger long enough to test the limits of one’s attention span. Although I never would have thought it when Frank Ocean first released his excellent twin 2016 records, Solange’s new release is the latest evidence that Ocean’s immersive, shape-shifting sonic collage Endless has become perhaps even more influential than his “official” album, Blonde.

The surprise(-ish) release of When I Get Home was accompanied by a 33-minute music video, which provides sumptuous visuals for nearly every song. The project is in some sense a rumination on the Knowles’s hometown of Houston, though perhaps as seen through outer space: The visual aesthetic is a vivid swirl of cowboy culture, Afro-futurism, and Southwestern American land art. (Imagine New Amerykah: Part Marfa, or Jodorowsky’s Westworld.) Solange moves with the slow-motion poise she perfected in the videos and live performances that accompanied A Seat at the Table. Given her background and early aspirations, choreography, movement, and visuals are not accessories to these songs so much as deeper expressions of their overall vision. What Solange always seems to be telling us with her kinetic grace is that, in a frantic and senseless world, to move slowly and with intention is its own kind of power.

Still, she gives us some cracks in the facade. One of my favorite parts of the When I Get Home visual is a montage—set to the space-reggae of “Binz,” one of the album’s highlights—of Solange recording herself dancing, in footage that looks to be shot on an iPhone. In a T Magazine profile from late last year, Solange revealed that this is how she comes up with much of her choreography: “Staccato or swaying movements, many of which developed from iPhone videos she made of herself daily—sometimes without music—formed the basis of a radically new kind of live performance.” Her inclusion of these rough drafts reminds me of what she said about the cover of A Seat at the Table and her decision to be photographed with clips still in her hair: “I wanted to put these waves in my hair, and to really set the waves, you have to put these clips in. … It was really important to capture that transition, to show the vulnerability and the imperfection of the transition—those clips signify just that, you know?” But in imperfection, perhaps even more than in its opposite, there can be joy. As she’s dancing in front of her phone, Solange’s face reveals the sheer glee not just of movement, but of the act of creation.

People are calling When I Get Home Solange’s surprise album, but for many listeners A Seat at the Table was, and remains, the true surprise. That record was a fully formed and immaculately executed reimagining of Solange’s vision. It caught the world off guard. When I Get Home is not a complete reinvention, but more of a reset, or a movement skyward: “Let’s do that again, but this time on the moon.”

This Solange record speaks much more abstractly than the last. When I Get Home lacks those startling moments of clarity that made its predecessor so powerful—the direct assertion of “Don’t Touch My Hair,” the plainly searching “Where Do We Go?”—and those hoping for more of the same might find this new record challenging, obtuse, or impersonal. But, as ever: Solange moves in no particular hurry. This is not the sort of album that reveals all its secrets on the first listen, or even the 15th (perhaps that is another way it feels at odds with the reality of the physical world in 2019, our year of quick hits and continual distraction). It took me several tries to get oriented to this record’s strange gravity, but once I did I found it to be inviting, adventurous, and even playful. (See: the Gucci-centric adult nursery rhyme “My Skin My Logo” or the crystalline reverie “Stay Flo.”) And if you take the time to decode it, this surreal ode to Houston is at times also deeply personal. Take the first interlude, “S McGregor,” which features H-town’s own superstar sisters Phylicia Rashad and Debbie Allen reciting part of a poem written by their mother. In her own way, Solange is at last fulfilling her childhood dream of being Debbie Allen, the girl whose older sister’s fame couldn’t keep her from becoming herself.