Kevin Kline didn’t want to be the leader of the free world. That bothered Ivan Reitman. The filmmaker, of Animal House, Stripes, and Ghostbusters fame, had agreed to direct a comedy about a fictional United States president. There was a script by Gary Ross, who’d written Big, but no star was attached yet.

“I think the cliché about him was that he was called Kevin ‘De-Kline,’” Reitman told me. The actor had little interest in the project. “I was really frustrated,” Reitman added, “and thought I was gonna lose the movie.”

Then Reitman called in a favor. One of his neighbors was Lawrence Kasdan. The writer-director had worked with Kline on The Big Chill. Reitman asked his friend to read Ross’s script. “Larry,” he recalled saying, “I’ve been trying to get Kevin Kline to do this movie. I think it’s perfect for him.”

Reitman thought that Kline, a few years removed from earning a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role in A Fish Called Wanda, possessed both the dramatic and comedic chops needed for the part. Kasdan concurred and got in touch with Kline. Reitman and the actor soon had lunch in Atlanta, where the latter was shooting the 1992 thriller Consenting Adults. It turns out that Kline was worried that Reitman was looking for him to deliver something similar to his over-the-top Academy Award–winning performance. Their meeting calmed the former’s nerves.

“I thought he was casting me for all the wrong reasons,” Kline told Variety last year. “But when we spoke, I knew in 30 seconds he wanted something totally different. We were absolutely on the same page about what it should be because it’s not a farce. It’s a very delicate sort of romantic comedy.”

On the surface, the premise of what became Dave was simple. The cold, calculating president has a debilitating stroke while having an affair with a young aide, and an amateurish, everyman impersonator, who exactly resembles the president, is secretly recruited to be his stand-in. For the movie to move beyond mere slapstick, however, it required a uniquely versatile lead. What excited Kline was that he would be playing three different characters: President of the United States Bill Mitchell, POTUS double Dave Kovic, and a ’90s version of Vaughn Meader. “As soon as I put it that way to him, his actor chops took over,” Reitman said. “He’s such a spectacular, pure actor that he really got intensely involved.”

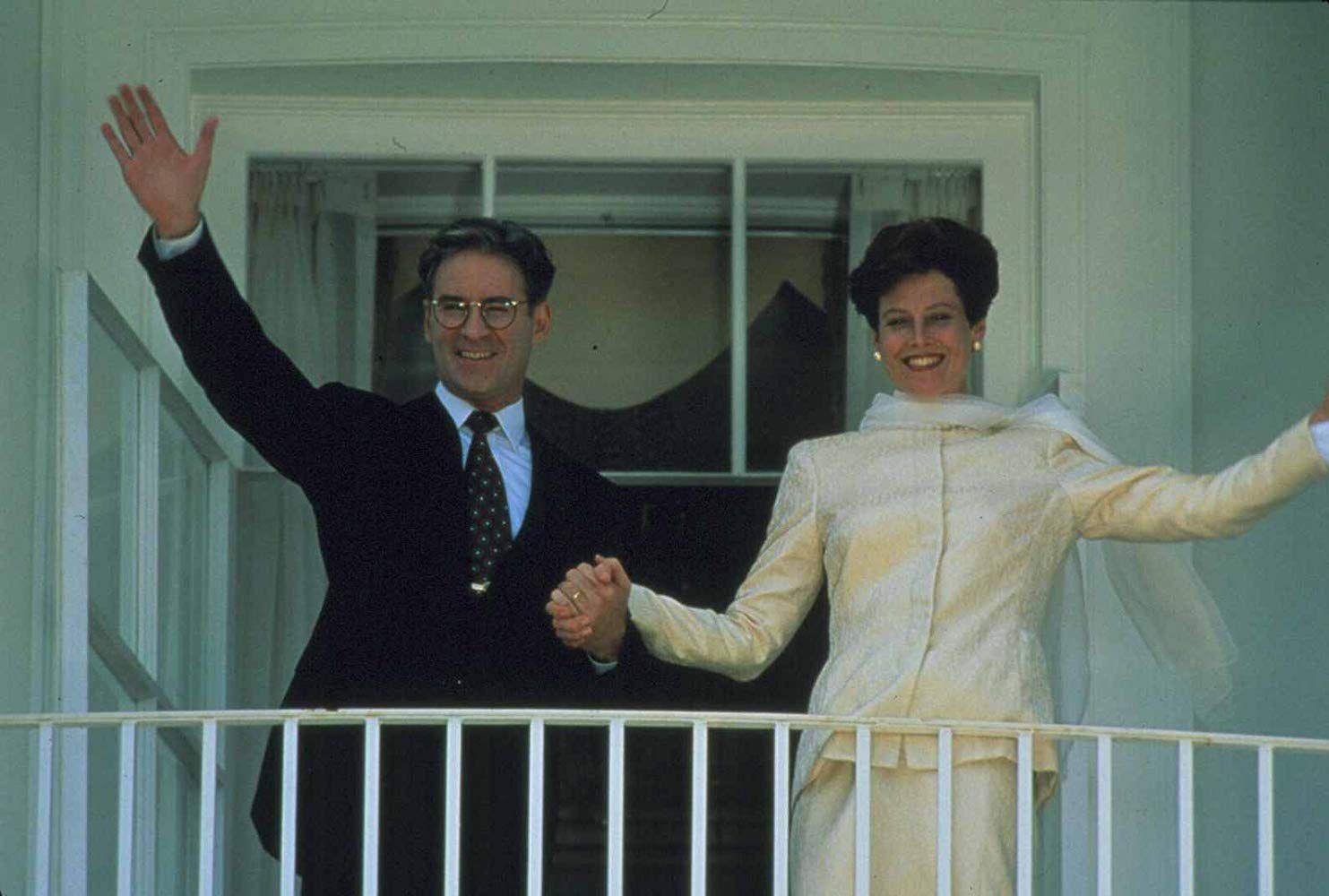

Released in the spring of 1993 with Kline in the title role, Dave was one of the decade’s most clever and prescient romantic comedies. It’s an unabashedly optimistic fairy tale, which today makes it all the more likable.

“That movie just gives you that twinge that Mr. Smith Goes to Washington does,” said Kevin Dunn, who plays Alan Reed, the president’s communications director. “It’s one of those kinds of films that gave you hope. It’s not propaganda. It’s just, ‘Boy, too bad things aren’t like this.’”

As much as Reitman wanted Kline, the actor’s presidential term almost never began. It was, in fact, Warren Beatty who brought the project to the director. The Hollywood legend, who’d just come off comic strip adaptation Dick Tracy (1990) and gangster biopic Bugsy (1991), thought Reitman would be the right person to helm the production.

On first read, Reitman fell in love with Ross’s script. “Usually when I get that strong a feeling about the story it’s because I think of some universal ideas that resonate in the humanity of most audiences,” the director said. “And those are the movies that tend to sort of stay in the consciousness. I had a theme in my brain, which was that the common man actually knows how to solve very straightforward problems, because he’s not weighed down by all the politics of the conflict.”

The story may have been a fantasy, but it was conceived by someone with real-life political experience. In 1988, Ross worked on Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis’s presidential campaign. The screenwriter later fed jokes to president Bill Clinton. “A lot of people can write funny lines,” Dee Dee Myers, then Clinton’s press secretary, told the Los Angeles Times in 1993. “But Gary can write a joke which also incorporates the candidate’s message and that’s fairly unique.”

Reitman was excited about making Dave, but there was a problem: According to the director, Warner Bros. didn’t want Beatty to star. At that point, Reitman balked. “I walked away from it,” he said. “It became to me one of those impassable situations.” Doing the movie without Beatty, Reitman added, would’ve been “morally wrong.”

Some time later, Reitman said, the studio told him that they’d cast Beatty as Dave. The director called to give him the good news, but Beatty wasn’t exactly thrilled with Warners’ offer.

“I think he was annoyed,” Reitman said. “They’d been trying to make a deal with him. He kept arguing with me that they’re not stepping up properly. I actually volunteered a piece of my back end to make his back end even more attractive. But he wouldn’t make a deal.

“I said, ‘Look, I’ve waited for a couple months, I’ve walked away from this, but now I’m prepared to go make it and you can do whatever you want. I’ve given you a piece of my back end. And now you have to say yes. I’m giving you five days. And if you don’t come back and agree to this I’m gonna try to find somebody else.’”

Beatty never phoned him back. “He was quite angry at me for a while,” Reitman said. “But I had to go forward. Because I had a feeling about this.”

Before Kline signed on, Reitman said that he sent the script to two of the era’s biggest box office draws: Kevin Costner and Tom Hanks. Neither responded. (Robin Williams and Michael Keaton were also rumored to be in the running.) Still, Reitman believes that Kline was the best man for the job. Surrounding him were some of the greatest character actors of all time.

“It’s one of those movies that doesn’t really happen anymore, where there’s a dozen great roles,” said Dunn, whose CVS-receipt-length résumé includes parts in Chaplin, Nixon, Godzilla, I Heart Huckabees, Transformers, and Veep.

I had a theme in my brain, which was that the common man actually knows how to solve very straightforward problems, because he’s not weighed down by all the politics of the conflict.Ivan Reitman

Sigourney Weaver injects her character, first lady Ellen Mitchell, with a searing bitterness, which she privately directs toward (the man she believes to be) her powerful, adulterous husband. She rightfully feels that he’s traded in his integrity for unfiltered ambition.

In Ghostbusters, Reitman saw Weaver’s character as Marx Brothers foil Margaret Dumont. In Dave, her sparring partner is much different than Peter Venkman. “She’s smart enough that she can handle either in their different sort of power,” Reitman said. “She loved working with Kevin. They were very funny together. She loved to make fun of his actorliness.”

The embodiment of the kind of cold-hearted cynicism critiqued in Dave is domineering White House chief of staff Bob Alexander. He enables Mitchell and then orchestrates his own power grab when the president falls ill. Frank Langella plays him with a level of dourness that’s both hilarious and scary. Visually, he reminded Dunn of president Richard Nixon’s henchman H.R. Haldeman.

“He was an extraordinarily important character because there’s nothing foolish about him whatsoever,” Reitman said. “He’s powerful and he’s strong enough just to really epitomize evil. And we needed real evil in the movie to make the stakes really meaningful.”

Reed is Alexander’s kinder, slightly less diabolical accomplice. Dunn loved playing off Langella. “He kind of has that demeanor that demands attention,” said Dunn, who plays Charles Colson in Oliver Stone’s Nixon. “If you look at the role itself, it’s incredibly funny, but he’s really quite a sinister fellow. You know? It was easy to get into working with him.”

Charles Grodin steals his scenes as Dave’s accountant buddy Murray, who helps the fake president tinker with the massive federal budget. “If I ran my business this way,” Murray says while going over the books, “I’d be out of business.”

It’s not just Grodin who makes the most out of limited screen time. Ving Rhames as stoic Secret Service agent Duane Stevenson, Ben Kingsley as Vice President Gary Nance, Faith Prince as Dave’s ex-wife and business partner Alice, Laura Linney as the young woman with whom Mitchell has an affair, and Bonnie Hunt as a White House tour guide are all memorable.

Kline actually plays a key supporting role himself: the president. In only a few minutes at the beginning of the movie, he portrays the shrewd Mitchell as icier than the Reflecting Pool in January. He’s truly the polar opposite of the naïve but sincere Dave. The film wouldn’t have been nearly as resonant as it is without that sharp contrast.

“It takes a really strong person to really hang onto all sides of himself,” Prince said. “You could see Kline could go to any point. He could have rage.” In other words, she added, “He’s a great fuckin’ actor.”

For Dave to work, the movie needed to capture what it would feel like for an ordinary citizen to be thrust into America’s most stressful, high-profile job. Dave’s sense of terrified wonder was enhanced by the work of J. Michael Riva. The production designer, who died in 2012, painstakingly reproduced the interiors of the White House. (The Los Angeles–situated set was so accurate that Warners later lent it to other productions.)

There’s an early scene where Alexander and Reed explain to Dave why they’ve summoned him to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. After processing what the two crooked cabinet members are saying, Kline jumps up from the president’s chair in the Oval Office, hurriedly backs away, and mutters, “Wait a minute …” three times and then asks, “What about the vice president?”

Kline plays his confused shock subtly, which helps sell the moment’s plausibility. He manages to sprinkle the movie with bits of physical comedy that land without being cloying—e.g., the look on his face when the first lady sees Dave naked in the shower and a well-executed chair pratfall.

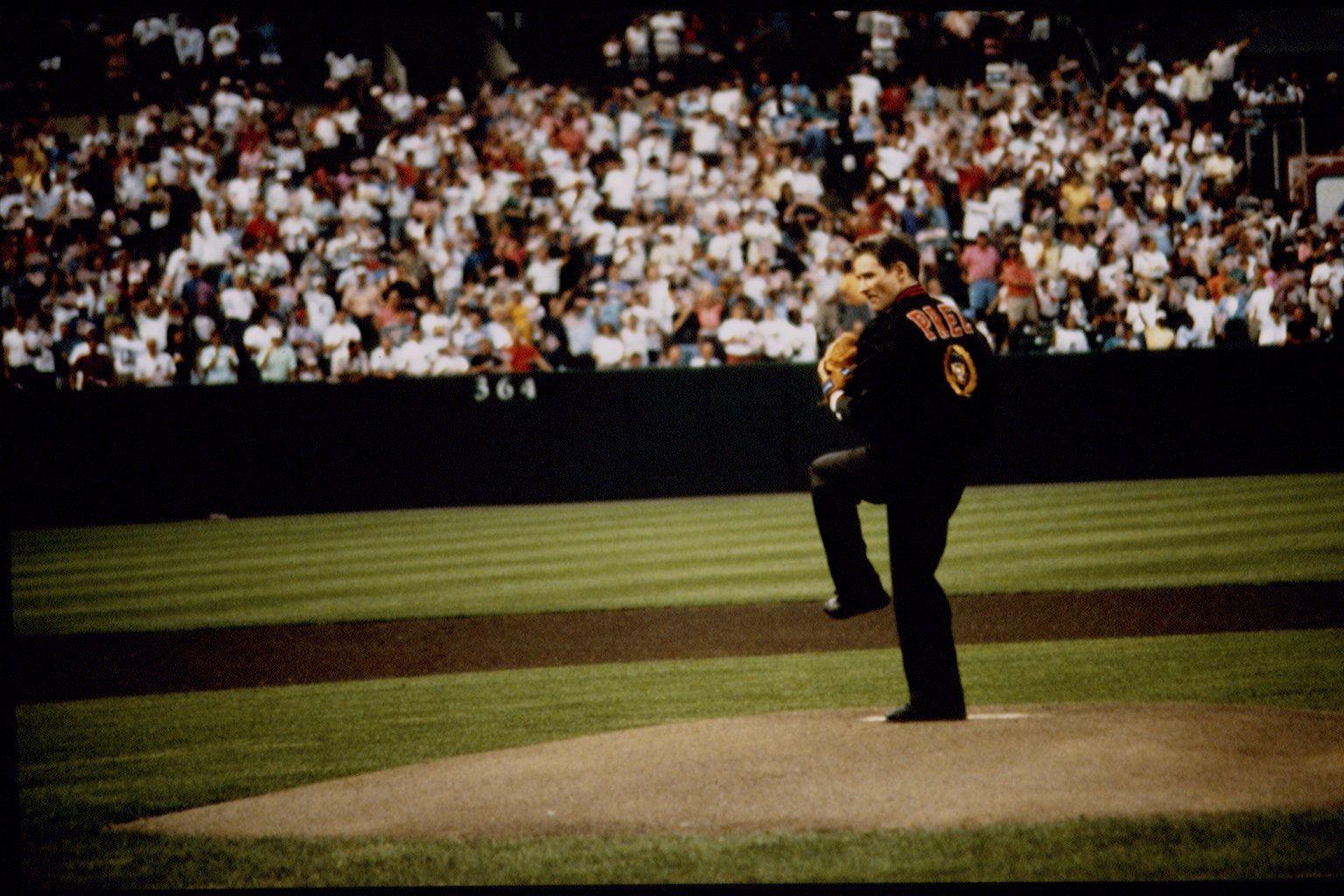

No stage was too big for Kline. One of the first things Reitman shot was in Baltimore in front of almost 46,000 fans. Before an Orioles game at the newly opened Camden Yards, Dave throws out the ceremonial first pitch. It reportedly took four takes for him to almost find backup catcher Jeff Tackett’s glove. “No matter,” The Baltimore Sun stated, “Mr. Kline jabbed the air in victory and accepted the cheers of the mob as he jogged off the field.”

The on-location portion of filming was relatively short, but to those involved it was a blast nonetheless. The movie is filled with cameos by Beltway insiders, including politicians, pundits, and journalists like Christopher Dodd, Chris Matthews, and Helen Thomas. (Famously cranky Wyoming senator Alan K. Simpson doesn’t appear to be acting when he’s ripping Mitchell’s new, Dave-aided compassionate policy agenda.) Prior to one scene, Dunn remembered sitting in a Capitol Hill bar while longtime Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill held court. It was, Dunn said, an “old musty place that smelled of old cigars and bags of money.”

The night of Clinton’s surprising 1992 presidential election victory, some of the cast attended a crowded party at the home of often-parodied political roundtable show host John McLaughlin. That evening, Dunn said that he ran into former Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee and CNN’s Larry King, the latter of whom briefly appeared in Dave.

“I just pretended I was Ben Kingsley’s bodyguard,” Dunn said. “I was just like, ‘What am I doing here?’ I kept thinking they were gonna find out that I was a fraud.”

Fortuitously, Washington, D.C., was the site of one of the movie’s most vital sequences. More than halfway through filming, Reitman watched a cut of the footage assembled by editor Sheldon Kahn.

Initially, after the first lady figures out that the man she believes is her husband is in truth Dave, the two sneak out of the White House in a car, go on a drive, and come back. The scene was supposed to bring the pair closer together, but the director didn’t buy that it did. So he called Ross.

“I said, ‘They’re not close enough yet,’” Reitman said. “I thought we needed another scene. They’d have to do something romantic together. And we started talking about them maybe getting stopped by a cop. We needed some adventure for the two of them to go through that allowed them to bond, to trust each other.”

Reitman and Ross then pulled from the rom-com playbook. Dave makes an illegal left turn, an officer pulls him over, and the fake president and his passenger are asked to step out of the vehicle. In the process, the policeman is certain that he’s staring at the real first lady. To cover for her, Dave claims that they’re look-alikes. Then, to further distract the cop, he and (eventually) his companion break into “Tomorrow” from the Broadway musical Annie.

The problem, according to Reitman, was that he didn’t have the rights to the song. Somehow, while standing on the streets of D.C. one night, he got Ray Stark on the phone. The producer, who helped adapt the play for the screen for Columbia Pictures, needed to give his blessing. Reitman tried to explain the scene to Stark. “I don’t think he understood what the hell I was talking about,” the director said. “But he said, ‘Look, as long as you promise you’re not making fun of the song, I’m gonna give you permission. But just remember, you owe me.’”

Reitman isn’t sure what the late Stark thought of the scene. He never heard from him again.

The movie was the product of someone who, like a good politician, could improvise when necessary. “I had the good fortune of working with all these extraordinary Second City and National Lampoon actors that are used to being quick on their feet, forcing me to be quick on my feet,” Reitman said. “Applying it to a more dramatic, traditional film like Dave was actually really great.”

The director claimed that Grodin’s best lines came from the actor. And Reitman said that Stevenson deadpanning to Dave that he doesn’t wear sweaters because they “make my neck too thick,” was all Rhames, who was a year away from his star turn in Pulp Fiction. For the cast, the atmosphere Reitman fostered was freeing.

“I’ve worked with a couple of really great people that should never do comedy,” said Prince, whose character in the movie runs an employment agency with Dave. “Because they’re too fucking controlling.”

On May 7, 1993, Dave hit theaters. It took a while for the the film’s box office receipts to build up—in total it made about $63 million against a budget of $28 million—but it quickly became a favorite among critics.

“I imagined that Dave would be completely predictable. I was wrong,” Roger Ebert wrote. “The movie is more proof that it isn’t what you do, it’s how you do it: Ivan Reitman’s direction and Gary Ross’s screenplay use intelligence and warmhearted sentiment to make Dave into wonderful lighthearted entertainment.”

Of course, at the time that review was written, Clinton’s presidency was still in its honeymoon. Whitewater had not reached a roiling boil. And while the POTUS was known to have been unfaithful to his wife in the past, the sexual misconduct allegations made against him had not yet entered the public consciousness. In the ensuing months and years, a film about a once-promising, power-abusing Democratic president seemed less lighthearted than at the time of its release.

When scandals began to submerge Clinton, Reitman was stunned. “We thought, ‘Holy shit,’” he said. Even though the 42nd president turned out to be more like Bill Mitchell than Dave Kovic, Clinton supposedly liked the movie. So did president Barack Obama, who reportedly told Kline that he enjoys it because the actor made being the commander-in-chief look easy. (Obama also apparently is fond of the far more cutting Bulworth, which happens to star Beatty as a campaigning senator who refreshingly decides to abandon civility for honesty. In 2013, The New York Times reported that Obama “has talked longingly of ‘going Bulworth.’”)

For his witty script, Ross was nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. “The plot unfolds with elements that would be at home in a Frank Capra movie,” Ebert observed correctly.

The movie’s intricate climax is indeed Capraesque. It’s a fittingly twisty, idealistic, uplifting, bittersweet, unrealistic but satisfying Hollywood ending. After all, Dave is a cynicism-free fairy tale. We wish it could come true, even if there’s no way in hell that it will.

“I love what it says about us as Americans and what we want and hope for and pray for,” Reitman said, “and the frustration of not getting it.”