There’s a good chance that 2019 will yield one of the weakest Best Picture winners in history. The eight films vying for the big prize constitute a deeply flawed field in which several competitors boast one or two outstanding elements—from Roma’s camera choreography and BlacKkKlansman’s topical provocations to A Star Is Born’s smartly tarnished glamour and The Favourite’s psychosexual complexity—but it doesn’t necessarily look like any of them will have real staying power. (If we’re talking strictly in terms of box office, Black Panther is an all-timer, albeit one destined for an Avatar-style tech-prize haul rather than a Titanic-slash–Return of the King sweep.) Last year at this time, everybody (well, not everybody) was infatuated with The Shape of Water, a movie that hasn’t exactly lingered in the popular consciousness; if durability in contemporary film culture is a matter of being able to simultaneously inspire serious exegesis, casual rewatchability, and top-tier memes, I’d say nominees like Get Out and Phantom Thread have jumped out to a lead that will only get longer as time goes on.

Complaining about The Shape of Water—or any contemporary Best Picture winner—on the grounds that “they don’t make ’em like they used to” is essentially a reactionary lament, and it’s also not necessarily true: The Oscars have been rewarding undeserving garbage on and off for their entire history. We all know the greatest hits of bad calls, whether it’s Mrs. Miniver over The Magnificent Ambersons or Dances With Wolves over Goodfellas or The King’s Speech over The Social Network; we also know that the list of major American movies not even nominated for Best Picture—Singin’ in the Rain, The Searchers, The Manchurian Candidate, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Mikey and Nicky, Killer of Sheep, Blow Out, RoboCop, Do the Right Thing, Heat, The Big Lebowski, Mulholland Drive, Zodiac—is probably more impressive, title for title, than the roll call of champions.

That said, there are a handful of Best Picture winners that were not only deserving in their moment but have stood the test of time, which gave me the idea for a Best Picture Championship Belt. Applying a WWE-style mentality to artistic evaluation is stupid, which is why it’s so fun. I’ve figured out a format that I think works and roped Sean Fennessey—who has been known to participate in thought experiments on this website—into a contest to determine the one Best Picture winner to rule them all.

The Rules:

1. I decided that we should start in 1968—meaning the 1969 Oscar ceremony—in order to keep the back and forth to a manageable length. So right off the top, there’s an asterisk, but hopefully 50 years’ worth of contenders is enough to give the debate breadth and scope. If that means that fans of movies like Gone With the Wind, How Green Was My Valley, On the Waterfront, and In the Heat of the Night feel like they’re being ducked, they should feel free to tweet angrily in our direction.

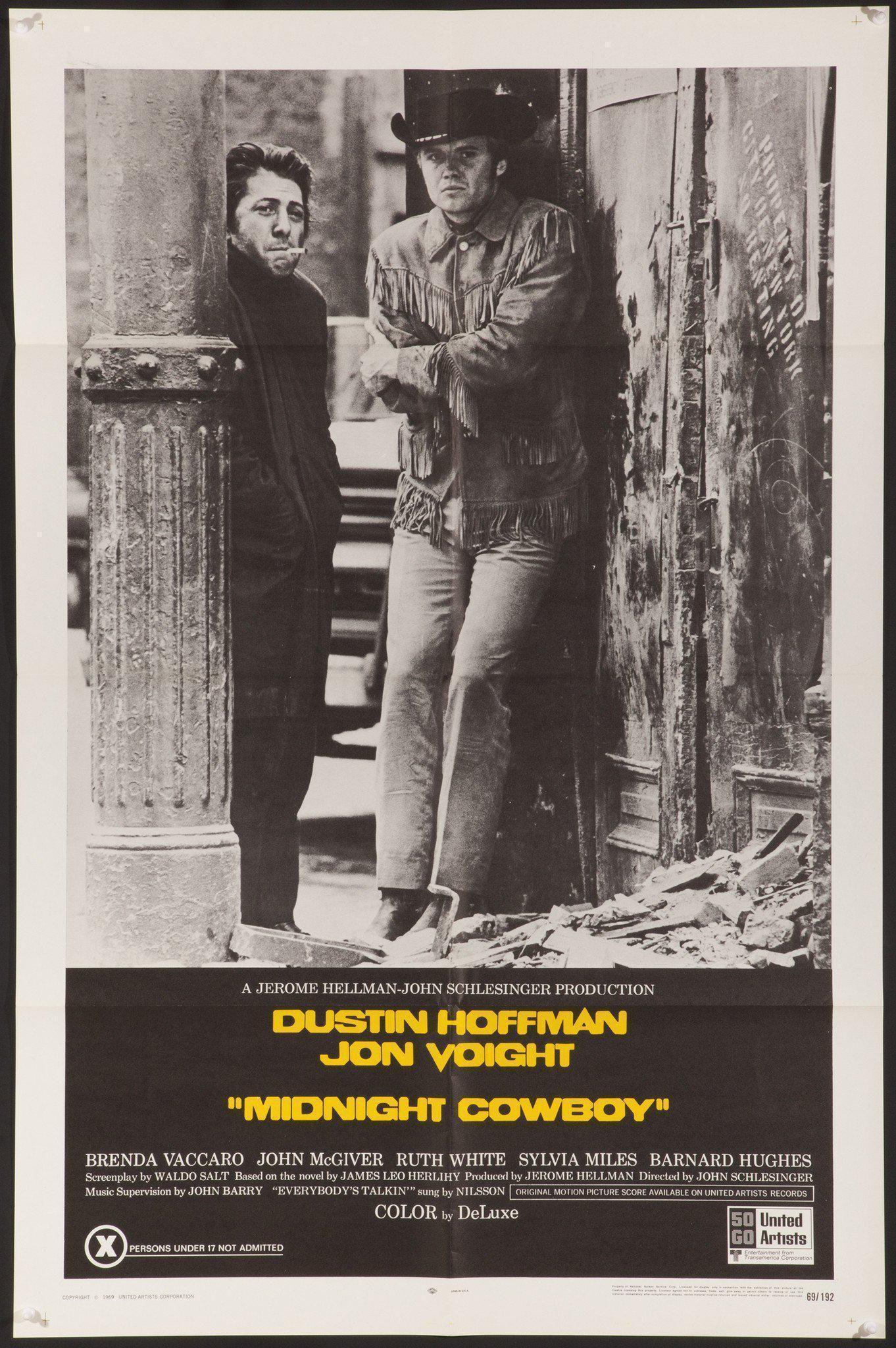

2. The criteria for victory here are derived from Ric Flair’s wisest maxim: “To be the man, you gotta beat the man.” Oliver! won Best Picture in 1968, so it starts out with the championship belt draped over its ratty, malnourished shoulders and holds it until whoever is going first—that’d be me—decides that a subsequent Best Picture winner is better. At which point, that film becomes the champion. Oliver! is a saggy, G-rated musical that features rows and rows of chirpy urchins singing about the virtues of pickpocketing; Midnight Cowboy, which won Best Picture in 1969, is an X-rated examination of masculinity and loserdom featuring epochal performances by Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman and a theme song by Harry Fucking Nilsson. Basically, Oliver! is Bob Backlund, and Midnight Cowboy is Diesel powerbombing him to death in eight seconds. Sean, you’re up.

Previous Champion: Midnight Cowboy

Reign: 1969-71

Defeated: Patton (1970)

New Champ: The French Connection

Fennessey: Thanks, Adam, I’m already wheezing like Popeye “Bad Santa” Doyle in pursuit of a perp. Apologies to Patton, a cleverly constructed and important-seeming biopic, but hardly a classic. If Midnight Cowboy represented a crack in the foundation of the genteel propriety that had defined the previous 40 or so Best Picture winners, then The French Connection, William Friedkin’s frantic NYPD cop drama, was a full-blown breakthrough. Friedkin’s bustling handheld camerawork and brutally straight-talkin’ characterizations redefined “Oscar winner” as we knew it. The film is based on a nonfiction book by Robin Moore (who also wrote “The Ballad of the Green Berets”) and introduced a kind of verite narrative style heretofore unseen at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. The French Connection has had staying power, and it set up Friedkin for his masterpiece, 1973’s The Exorcist. But I don’t think its time on top will last long in our formulation.

Previous Champion: The French Connection

Reign: 1971-72

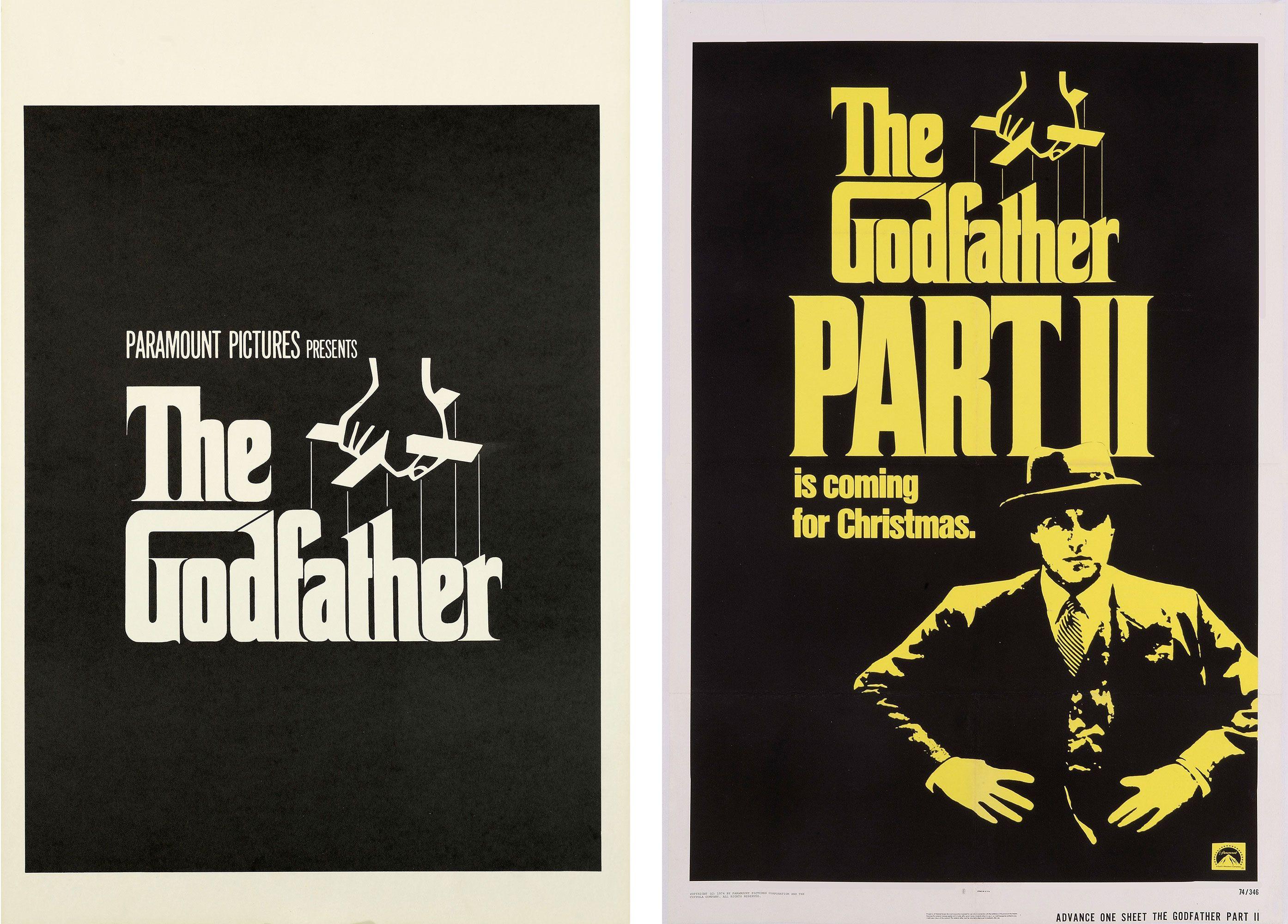

New Champ: The Godfather

Nayman: You brought this on yourself, Sean. If only you’d told a little white lie and suggested that Patton, a “cleverly constructed and important-seeming biopic,” was better than Midnight Cowboy. A hot take, but not so scalding that anybody would have noticed. You would have forced my hand: I’d have had to go with the The French Connection here and let you have The Godfather, which is only one of the most famous, successful, enduring, influential, quotable, rewatchable American films ever made and the highest-ranking Best Picture winner on the venerable Sight and Sound list of the top films of all time. I could go on and on about the acting, the direction, the music, the themes, the cannoli, or the way that Francis Ford Coppola simultaneously redrew the boundaries of Old and New Hollywood by seasoning the raw, bloody pulp of Mario Puzo’s novel with art-film flavors. I could talk about the filmmaking’s exhilarating mix of Hawks, Visconti, and Peckinpah, or the sheer, overwhelming power of the script’s class and ethnic allegories. I could, but I don’t have to, because if we extend the wrestling metaphor, The Godfather is Bruno Sammartino—an Italian American juggernaut running roughshod over the early-’70s competition, and not required to job for anybody.

The French Connection is surely great, and, as you suggest, it softened up the Academy even more than Midnight Cowboy for Coppola’s brutal, genrefied vision, which beat out a strong field, including John Boorman’s vicious Deliverance and Bob Fosse’s brilliant, devastating Cabaret. But The Godfather is better. It wins, and now you’re at a loss. Either you’ll boldly pick some other, subsequent Best Picture honoree to upset it in head-to-head competition, or this will end up being the shortest Ringer movie feature since “Three Takeaways From Sherlock Gnomes.” (I’m pretty sure I made up that title, but the point still stands.) So I’m gonna make you an offer you can’t refuse. We can (1) remove The Godfather (but not its overrated, similarly Best Picture–winning sequel, and yes, I went there) from the tournament as an acknowledgment of its outsize film-historical and cultural impact, leveling the playing field and creating a vacancy to be filled by your next pick, or (2) explain to your readership why you’re lobbying against a movie that has this scene. And this one. And this one. And this one. It’s not personal, Sean. It’s strictly business.

Previous Champion: The Godfather

Reign: 1972-74

Defeated: The Sting (1973)

New Champ: The Godfather Part II

Fennessey: As a megalomaniacal mafia don once said, I don’t feel the need to wipe everybody out, Adam. Just my enemies. And so, the joke’s on you. The Godfather may be the most rewatchable movie ever made, but its sequel is, I’m fairly certain at this stage of my life, the finest American film ever made—as wide as it is long, as operatic as it is entertaining. And if the original overcame two formidable opponents in Deliverance and Cabaret, then Part II overcoming two stone-cold classics in Chinatown and Coppola’s own The Conversation makes it that much greater.

Previous Champion: The Godfather Part II

Reign: 1974-76

Defeated: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

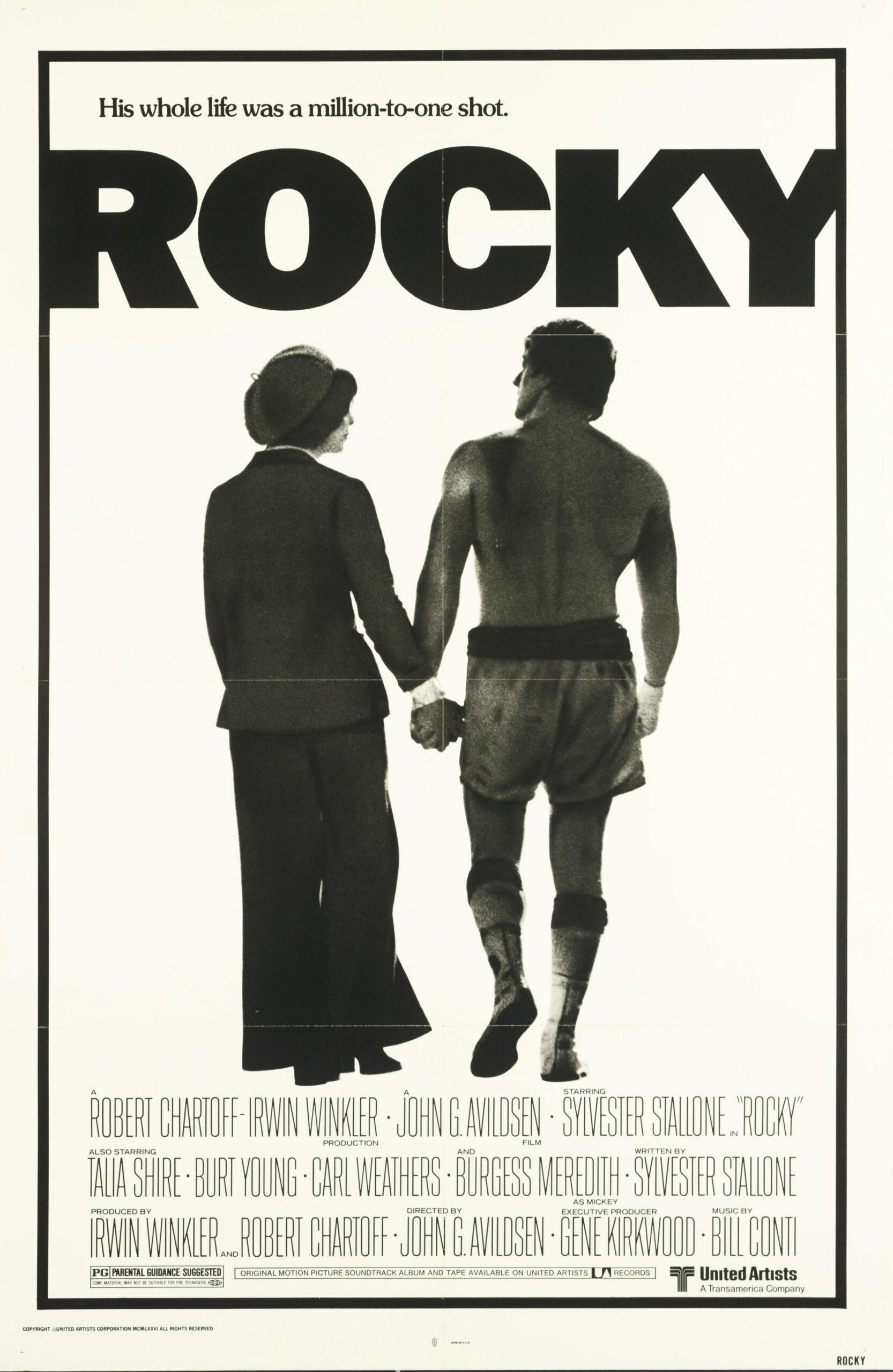

New Champ: Rocky

Nayman: As somebody who prefers both The Conversation and especially Chinatown—the finest American movie ever made about evil, if not of all time—to The Godfather Part II, I look at its win as a pure legacy move. Because it’s so hard to separate the initial installments of Coppola’s trilogy—a cohesion generated via the sequel’s admittedly ingenious wraparound, once-and-future Don narrative—they’re routinely hailed as a kind of collective masterpiece set in the MCU (the Michael Corleone Universe). But I’ve always thought Part II was hugely flawed, from the stilted Al Pacino–Diane Keaton throwdowns (“an abortion, Michael … just like our marriage is an abortion”) to the thematically redundant déjà vu of the protagonist’s descent into a moral and ethical dead zone—a journey already undertaken in the first movie, with less self-referential self-importance. I’m tempted, in fact, to let Godfather II get upset by its first challenger, Milos Forman’s stagy but sensationally effective adaptation of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but I’ll hold off and give the duke instead to Rocky, a great mainstream entertainment that stirs up every single big, shameless emotion in the book. In her New Yorker review, Pauline Kael compared the film’s then-unknown star to Marlon Brando, and I don’t think she was overdoing it. Sylvester Stallone’s gentle, unstudied acting both exalts and transcends the clichés of his screenplay, creating something rare in a movie decade defined by squirrelly, ambivalent antiheroes—an honest-to-god icon.

Previous Champion: Rocky

Reign: 1976-78

Defeated: Annie Hall (1977)

New Champ: The Deer Hunter

Fennessey: I could dissect some of the shrill, manipulative elements of Rocky in this space, but post-Process Philadelphians have endured enough indignity. Its inclusion does clarify something: Nearly every Best Picture winner of this era is set on the East Coast of the U.S. or oriented around characters born of the region. The New Hollywood was urbane, exceptionalist, and eager to demystify fairy tales. Rocky was the only genuinely optimistic film to win during the ’70s and, even then, it ends with its hero losing the big fight. (It also defeated three superior miserabilist masterpieces—Network, All the President’s Men, and Taxi Driver—for Best Picture.) Two years later, Michael Cimino’s brutal humanist Vietnam drama The Deer Hunter set the horrors of that war against the slowly dissolving blue-collar mining towns of the Rust Belt, in this case, Clairton, Pennsylvania. Its design is simple but perfect—before the war, the war, after the war. The three stars travel together from weddings to battles to funerals. It moves in threes. The image of a wild-eyed Christopher Walken locked in a deathless game of Russian roulette is the film’s lasting image, but all I can see is Robert De Niro, bearded and bereft, unable to reconcile his own trauma with the people back in Clairton thanking him for his service. The Deer Hunter is Oscary in the best way—self-important, sure, but a worthwhile culmination of a decade in which the Academy knew how important movies could be to a generation.

Previous Champion: The Deer Hunter

Reign: 1978-86

Defeated: Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), Ordinary People (1980), Chariots of Fire (1981), Gandhi (1982), Terms of Endearment (1983), Amadeus (1984), Out of Africa (1985)

New Champ: Platoon

Nayman: Considering that I wouldn’t have been born if not for Annie Hall—true story, ask me to tell it some time—I now regret not stumping for Woody Allen’s greatest movie in this space. Plus, it would have provided better ammunition for your “urbane and exceptionalist” argument than Rocky, which is more urban-populist. Anyway, I’m with you on Cimino’s towering, lingeringly problematic epic, a movie ambitious and arrogant enough to have its whole ensemble sing “America the Beautiful” to emphasize its status as national portraiture. In terms of size and scope, The Deer Hunter represented a culmination of the New Hollywood, as well as a bellwether of its hara-kiri-style demise, with all the easy riders and raging bulls falling on their own designer swords: Just as Cimino boldly parlayed its success into the uncompromised debacle of Heaven’s Gate, so too would Spielberg (1941), Friedkin (Sorcerer), Coppola (Apocalypse Now), and Scorsese (New York, New York) risk everything on pricey, relatively unprofitable vanity projects. The faceless, high-concept ’80s were on their way, with the majority of interesting, idiosyncratic American movies relegated to—or proudly stationed on—the indie-cinema margins; the general crappiness of the decade’s Best Picture winners proves it, although I guess a case can be made for Terms of Endearment or Amadeus. I myself will opt for some symmetry and let Cimino pass the torch—or the bayonet—to Oliver Stone’s Platoon, a leaner, meaner heir to The Deer Hunter’s mix of frantic action and antiwar critique. Stylistically twitchy, ideologically left-leaning, and more than a little manic, Stone ranks among the unruliest filmmakers ever embraced by the Academy, and while Platoon is far from perfect, it’s got the harsh, bludgeoning force of a major work. And now I’m really interested where you’re going to go next …

Previous Champion: Platoon

Reign: 1986-91

Defeated: The Last Emperor (1987), Rain Man (1988), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), Dances With Wolves (1990)

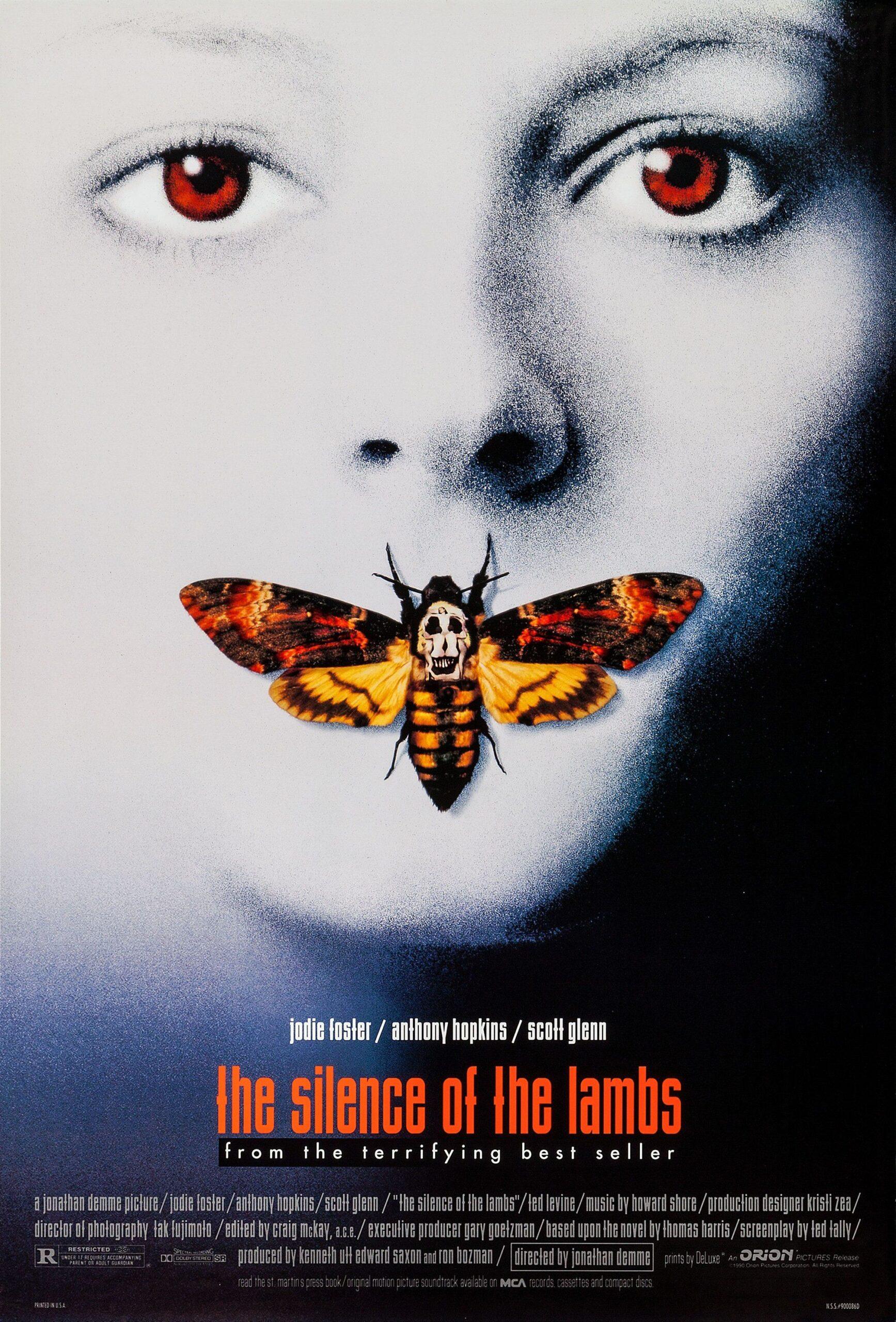

New Champ: Silence of the Lambs

Fennessey: I probably would have found room for James L. Brooks’s Terms of Endearment—a three-hankie weepie of a high order, a categorical strata of Oscar history that has fallen away in recent years. And given that we’ve passed over Forman for Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus, I fear we’ve made some sort of karmic error against the great Czechoslovakian filmmaker. Alas, here we are, in the ’90s, with my sweet dear Jonathan Demme, a polymath empath who blended serial killer mythology, crime fiction, emotional psychology, feminism, cannibalism, whodunnitism, and all kinds of other -isms to create The Silence of the Lambs, that rarest of Best Picture winners—a five-for-five winner in the major categories, a box office smash, a director’s pinnacle, a pair of legendary characters, and a universally agreed upon champ. I’m fond of JFK and Oliver Stone’s tinfoil tripping of the light fantastic, but there really wasn’t anything coming close to Lambs. Demme was a famously flexible creative, able to work in different styles and genres with ease—and I would take Something Wild and Stop Making Sense in my personal Demme rankings. But Lambs has the feel of right place, right time for everyone involved. It shattered that icky, faceless ’80s you referred to and ushered in a kind of heightened dramatic realism to big-top moviemaking that would influence Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, and several other directors who would grab the mantle later in the decade.

Previous Champion: The Silence of the Lambs

Reign: 1991-92

New Champ: Unforgiven

Nayman: Silence would probably top any reasonable poll of the weirdest Academy picks—I remember at the time there were all sorts of entertainment-section op-eds ([Extreme Morten Tyldum voice] today we call them “think pieces”) about what it meant that a horror film won Best Picture. What it meant, as you suggested, is that Demme’s skillful but sincere adaptation of Thomas Harris’s lurid best seller was the real deal, and it is: If there’s a more fully realized heroine in the Hollywood thriller canon than Jodie Foster’s well-scrubbed, hustling rube Clarice Starling, I don’t know her. But its reign will be short-lived around these parts nevertheless. On the whole, I prefer Demme’s earnest, lived-in humanism to Clint Eastwood’s solemn and often narcissistic mythmaking, but Unforgiven represents Ol’ Gray Eyes at his best—purposefully interrogating both his crackshot screen persona and the Western genre that supported it for decades. In the process, he earns something like a confession: “It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man,” croaks Clint’s William Munny, retroactively complicating characters from the Man With No Name to Harry Callahan and momentarily putting the sting back into death in American cinema. That thunderous moral authority, however short-lived, is something that not even Silence, with its mordantly murderous humor (“I’m having an old friend for dinner”) can claim. What’s nice, though, is that we’ve finally hit a little stretch of Oscar history when we can agree that the right movie won two years in a row—to paraphrase Unforgiven itself, “deserve’s got everything to do with it.”

Previous Champion: Unforgiven

Reign: 1992-97

Defeated: Schindler’s List (1993), Forrest Gump (1994), Braveheart (1995), The English Patient (1996)

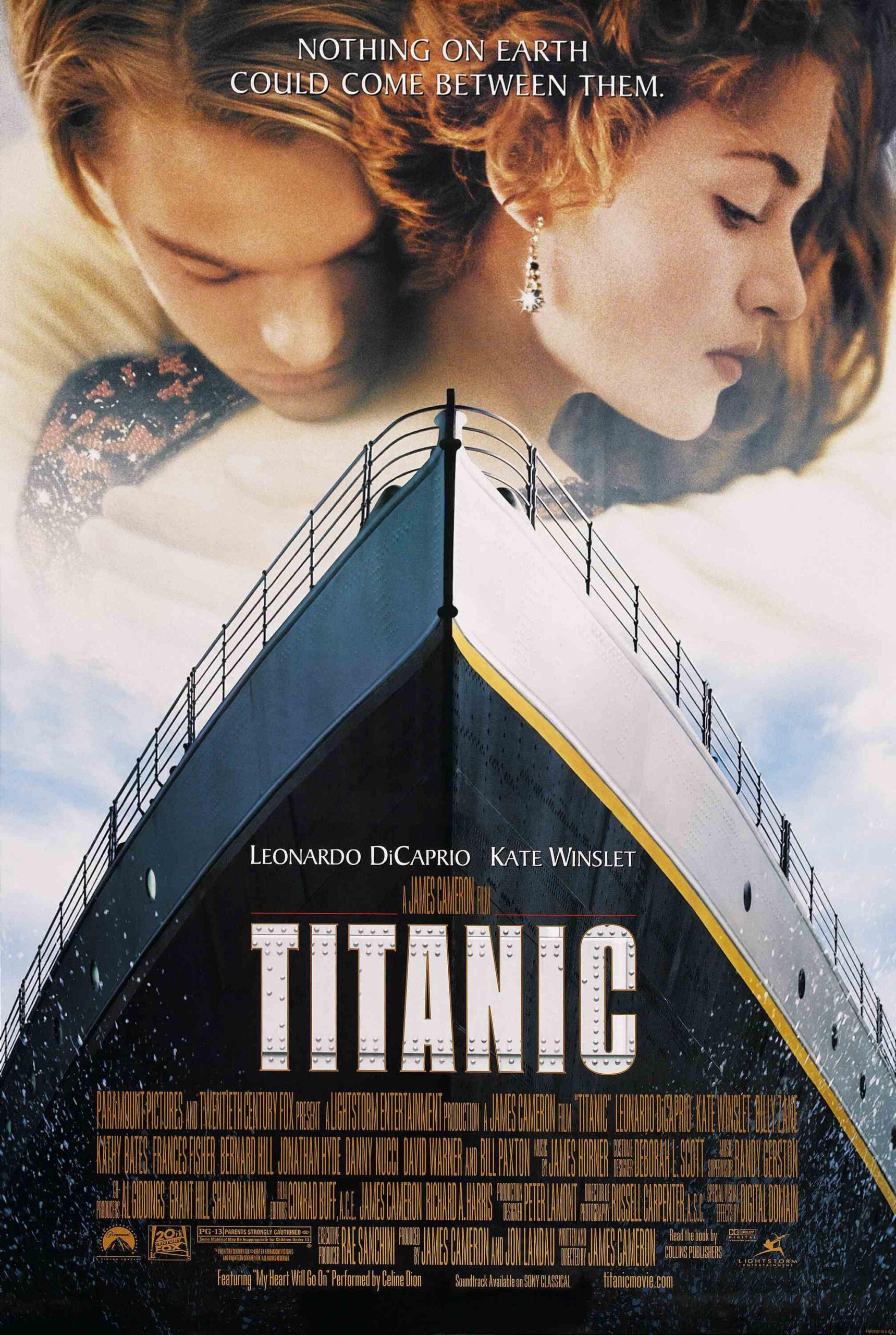

New Champ: Titanic

Fennessey: This is a new sensation, to bypass Best Picture winners I can recall actually winning the prize. Schindler’s List is the most difficult omission here, but when Steven Spielberg kicks the proverbial can, where will it rank among the films listed in his obit? Fourth, perhaps, behind Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Raiders of the Lost Ark? The historical docudrama’s self-conscious seriousness was a sidestep for the typically entertainment-first Spielberg, and while Schindler’s has a pensive majesty, it feels predetermined and, ultimately, preordained. Titanic, on the other hand, was a real-time shipwreck throughout its production, harebrained in its conception and short-armed in its budget, leading to one of the most cursed shoots of all time. A film is (theoretically) awarded an Oscar on its merit and not its degree of difficulty, but Ocean Master James Cameron constructed a new set of floating obstacles for himself. Titanic’s dialogue and characterization is … not great. But Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet give the kind of old-fashioned, starry-eyed performances that wouldn’t have been out of place in previous winners like From Here to Eternity or 1927’s Wings. The film’s breathless design and bottomless water tank of ambition made it a global sensation and I’m inclined to reward Cameron’s megalopolis mind here. Relatedly, how do you think we’ll look back on the ’90s as a movie decade? Trapped between the go-for-broke synth solo 1980s and the calcifying post-Sundance fest brats of the ’00s, it’s hard to know how to define the period that rewarded Forrest Gump and Braveheart in successive years. I guess there’s no accounting for taste at the all-time tastemakers awards show.

Previous Champion: Titanic

Reign: 1997-2003

Defeated: Shakespeare in Love (1998), American Beauty (1999), Gladiator (2000), A Beautiful Mind (2001), Chicago (2002)

New Champ: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Nayman: I’ll always look back on the ’90s as the decade I went from getting pulled out of five separate Pulp Fiction screenings as a junior high school kid in the summer of 1994 to walking into Jackie Brown on Christmas Day 1997 without any hassle—I used to be free / I used to be 17. In all seriousness, though, the ’90s were the decade in which Tarantino refashioned American film culture in his profane, postmodern image, and the fact he’s never won Best Picture doesn’t change the fact that, more than any single filmmaker since Spielberg, he’s changed the way the mainstream looks and operates. That includes James Cameron, whose increasingly enormous, technocratic epics don’t signify outward as much as they should (Titanic is as self-contained as an ocean-liner-in-a-bottle), and Peter Jackson, who steals JC’s King-of-the-World crown on points. Like the Academy, even if they couldn’t come out and say it, I’m rewarding The Return of the King on behalf of the entire trilogy and its integration of old-school, literary virtues with CGI wizardry. You have to admit, though, that the competition in between is pretty skimpy, reaching a nadir in 1999 with American Beauty, one of the worst movies to ever win Best Picture. It’s telling that when people rhapsodize about the bounty of great films that came out in the last year of the millennium, Sam Mendes’s sketchy suburban sitcom rarely comes up other than to criticize its cheesy surrealism, dated white-male-self-pity, and confused homophobia; as I don’t have anything nice to say about Gladiator, A Beautiful Mind, or Chicago, I won’t say anything at all and wait to see which side of Crash your vote lands on.

Previous Champion: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

Reign: 2003-07

Defeated: Million Dollar Baby (2004), Crash (2005), The Departed (2006)

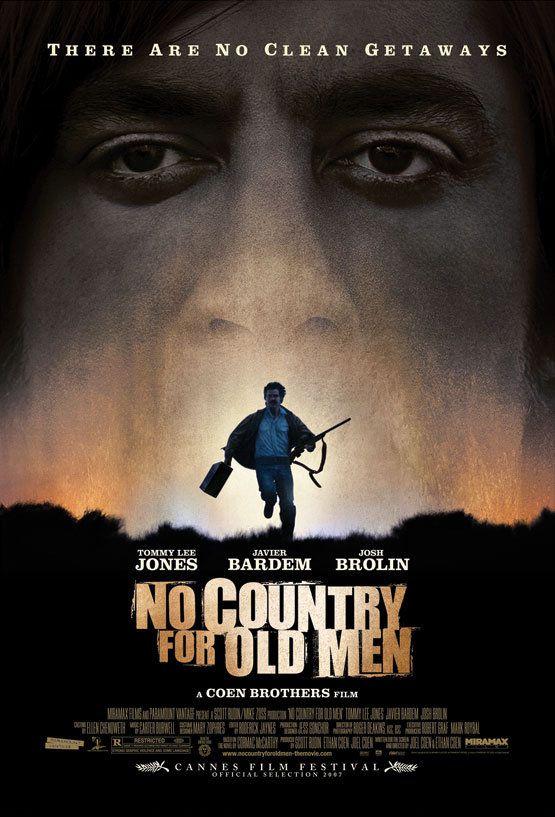

New Champ: No Country for Old Men

Fennessey: Oscar may have finally discovered the cocaine-brain and rock ’n’ roll ear of Martin Scorsese with The Departed, but that doesn’t mean I have to pretend it’s even in his top five. (Or top 10!) Likewise Million Dollar Baby, a well-made, austere examination of self-mastery and mentorship in a dying America, until it goes mega-maudlin in the final third. Give me Unforgiven for back-nine demythologizing, and call it a night. So where does that leave us? Certainly not with Crash, the only movie in the past quarter-century that exceeds American Beauty in abject awfulness. Crash is a cosmic gift for Oscar critics, a barometer of suck against which we can measure all the “Why can’t we all just get along?” plaints of future generations. So here we sit with your friends and mine: I sure feel like I just did this dance in celebrating the Coen brothers and their seminal Western noir adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel, and heaven knows you’ve spilled your fair share of ink on No Country for Old Men, and the Coens writ large. So let’s say simply: You can’t stop what’s comin’, it ain’t all waitin’ on you …

Previous Champion: No Country for Old Men

Reign: 2007-11

Defeated: Slumdog Millionaire (2008), The Hurt Locker (2009), The King’s Speech (2010)

New Champ: The Artist

Nayman: Just kidding.

Previous Champion: No Country for Old Men

Reign: 2007-16

Defeated: Slumdog Millionaire (2008), The Hurt Locker (2009), The King’s Speech (2010), The Artist (2011), Argo (2012), 12 Years a Slave (2013), Birdman (2014), Spotlight (2015)

New Champ: Moonlight

Nayman: “What’s this guy supposed to be, the ultimate badass?” Llewelyn Moss is being sarcastic, but that just about sums up Anton Chigurh, and also No Country for Old Men, which takes down eight contenders in a row—the most of any of our picks—before taking a hard-fought L against Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight. It’s a choice that I had to talk myself into, and not just because I’m hawking a book about Joel and Ethan. No less than Million Dollar Baby and The Departed, No Country played as an example of master filmmakers bending generic conventions to their will, while also channeling larger, post-millennial anxieties about American avarice and atavism. Its ambivalent portrait of a universe ruled by coin-flip indifference made it feel like either the last great thriller of the 20th century or the first of the 21st. No wonder the Academy quickly retreated into the shallow uplift of Slumdog Millionaire, and with the exception of Kathryn Bigelow’s fine—if schematic—The Hurt Locker, an Iraq-set companion to The Deer Hunter and Platoon, their post-No Country choices reflect a desire to back off from its bottomless philosophical abyss. Maybe not 12 Years a Slave, but I was never comfortable with Steve McQueen’s conflation of genuine historical trauma with austerely brutal showmanship; the aesthetic muscle-flexing of Birdman and reheated Pakula-isms of Spotlight don’t impress me much either.

What moved me about Moonlight as a Best Picture winner was how the surprise around the announcement gave way to a legitimate euphoria, both in the room and on social media—a sense that, with apologies to nice-enough-guy Damien Chazelle, a kind of justice had been served by rejecting La La Land’s weirdly reactionary razzle-dazzle in favor of something so lyrical, poetic, and palpably political. Its win didn’t seem premeditated so much as miraculous. And insofar as things like the Oscars matter—the way they can occasionally confer a heightened visibility and viability on worthy works—the industry-ratified triumph of an independently financed drama steeped in queer African American experience couldn’t help but feel like a rejoinder to larger forces. Moonlight was on TV the other night and I tuned in just in time for Kevin and Chiron’s reunion at the diner and drive back to Kevin’s apartment, a passage so pregnant with echoes of the past and anticipation of what could be that it threatens to burst. No Country’s vision of a world ruled by mercenary mercilessness is a flawless representation of what Cormac McCarthy would call Outer Dark, but Moonlight’s judicious rays of hope—the subtle, blue-tinged shimmer of its final shot—provide the illumination of true, enduring art. It’s been only two years, but I have no doubt they’ll flicker on.