In their incredible but also totally predictable run to the Super Bowl, Tom Brady and the Patriots offense have lined up against two of the most fearsome pass-rushing units in the NFL … and the future Hall of Famer has barely been touched.

It’s lazy to say that the book on beating Brady is to pressure him; that’s true for every quarterback. But it certainly is important, and that the Patriots are back in the big game hints at how the Chargers and Chiefs fared in that critical goal. In the divisional and championship rounds, New England went up against game-wrecking pass-rush talents like Joey Bosa, Melvin Ingram, Justin Houston, Chris Jones, and Dee Ford, and allowed a combined zero sacks and just three quarterback hits. The Chiefs and Chargers pressured Brady on just 15.6 percent of his dropbacks—a pressure rate that’s less than half the rate that any other quarterback has faced this postseason.

So how did the Patriots render top-tier pass-rush units irrelevant in two straight games? And can they make it three in a row this Sunday against Aaron Donald, Ndamukong Suh, and a fearsome Rams front?

I thought that the Patriots would have issues dealing with the nonstop pressure both the Chargers and Chiefs had been able to generate late in the year. Brady struggled at times this season with accuracy in the face of oncoming pass rushers, and after he notched a meager 71.2 passer rating under pressure this season—21st leaguewide and a huge drop from his league-best 96.6 mark from last year, per Pro Football Focus—it seemed likely that both L.A. and Kansas City would be able to create some havoc. I guess I should’ve known that Bill Belichick would have a plan to thwart all that.

New England had a two-pronged strategy for dealing with these elite pass-rushing units: run the hell out of the football and get passes out of Brady’s hands extraordinarily quickly. That sounds simple in concept, but it’s complex in practice. Success in both areas started with the team’s underrated offensive line, which has coalesced into an elite unit at just the right time. From left to right, Trent Brown, Joe Thuney, David Andrews, Shaq Mason, and Marcus Cannon have excelled in pass protection. Against the Chiefs, for example, that group recorded a pass block win rate of 90.5 percent, per ESPN, the top mark for any team in any game all year—displaying a level of coordination and communication that shouldn’t have been possible in the crowd noise at Arrowhead. Together with tight ends Rob Gronkowski and Dwayne Allen and fullback James Develin, the Pats have opened up big run lanes for the team’s versatile running backs group this postseason too. Rookie Sony Michel and veterans James White and Rex Burkhead have been the tip of the spear for the New England offense in its past two games, rushing for a combined 331 yards and eight touchdowns.

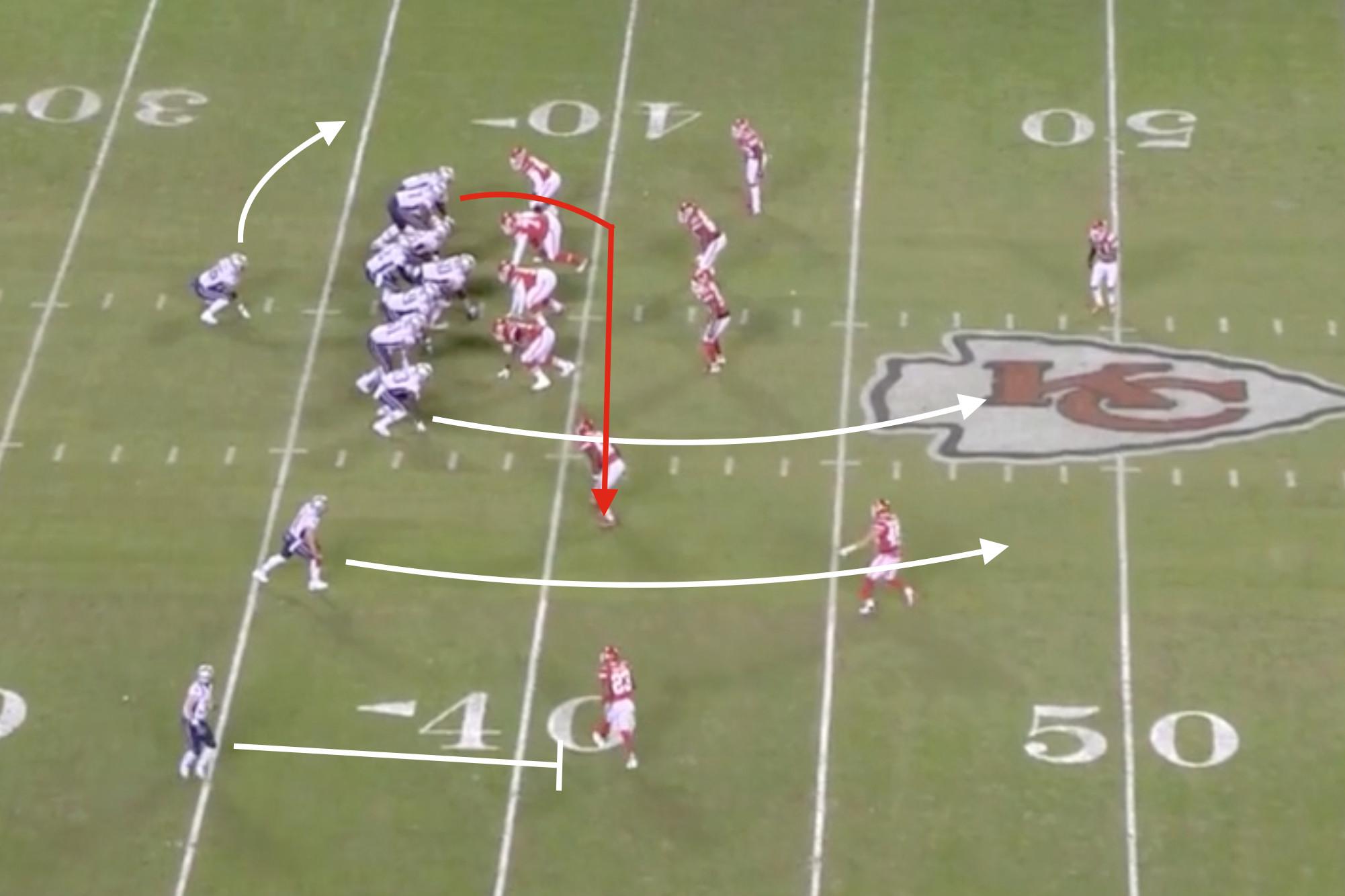

Together with offensive coordinator Josh McDaniels, grizzled offensive line coach Dante Scarnecchia has helped design a diverse, tough-to-defend run scheme. The Pats dug deep into their playbook in the championship round, throwing everything but the kitchen sink at the Chiefs’ oft-overwhelmed front. New England’s 15-play, 80-yard opening drive was the perfect microcosm for how they’ve utilized a wide variety of runs out of multiple personnel groups to confuse and disorient their opponents. As NFL Films maven Greg Cosell detailed on The Ross Tucker Football Podcast last week, the team’s seven first-down run concepts on that opening drive went in this order: an iso lead weak run out of 21 personnel (two running backs, one tight end), a counter run out of 22 personnel (two running backs, two tight ends), an outside zone run out of 22 personnel, an iso lead strong run out of 21 personnel, a zone counter run out of 11 personnel (one back, one tight end), an inside zone lead run out of 21 personnel, and an outside zone run out of 11 personnel. That’s just one possession, and only the first-down runs. Just take a look at the variation in how these plays started; in blocking, formation, personnel, run direction, and even Brady’s footwork.

It’s mesmerizing, and points to the skill of the Patriots offensive linemen, who’ve managed to execute a wide variety of run plays and styles at a high level. It’s also hell for a defense to prepare for this type of multiplicity.

Of course, the run game has been just one part of New England’s devious plan to dismantle its opponents’ elite pass-rush groups. Brady’s gone to work in the passing attack too: While the run game primarily attacked the middle of the field, Brady, McDaniels, and Co. made sure to soften up the edges of K.C.’s defense, throwing, for starters, a bevy of quick swing passes to their running backs. Here’s a sampling: Note how Brady uses his eyes to manipulate second-level defenders.

In this next play, Burkhead flexed out to the slot before the snap. When linebacker Reggie Ragland was slow to react to that motion, Brady just whipped a quick pass out to the wing.

The Pats also mixed in screen plays …

... and a few quick-hitting play-action tosses over the middle, using the threat of a run to suck the linebackers up to the line before throwing it over their heads.

New England stressed the K.C. defense both vertically and horizontally—methodically picking it apart by scheming its role players open. They got this easy first down with a quick pass to Develin, who leaked out of the backfield to, again, exploit Ragland’s lack of sideline-to-sideline speed from the middle:

And they got Cordarrelle Patterson involved with the offense, first with a jet sweep, then later with a swing pass out of the backfield.

Most of those plays—swing passes, screens, sweeps—were simple “constraint plays” meant to use the Chiefs’ aggressiveness in getting after Brady (or the run) against them. But the Patriots leaned on plenty of man- and zone-beater concepts to move the ball down the field too. Using motion to identify coverage schemes, Brady often knew who was going to be open before the ball was even snapped, allowing him to get the ball out quickly for efficient positive yards.

On this third-down play, the Pats spread things out with a three-by-one set with Julian Edelman in the tight slot to the left. Brady sent Edelman across the formation and when the defender followed, it signaled man coverage for the Chiefs. Knowing Gronkowski (aligned on the wing to the right) would carry his defender up the sideline, it was an easy read for Brady, who hit his playmaking receiver on a quick out route past the sticks for a first down.

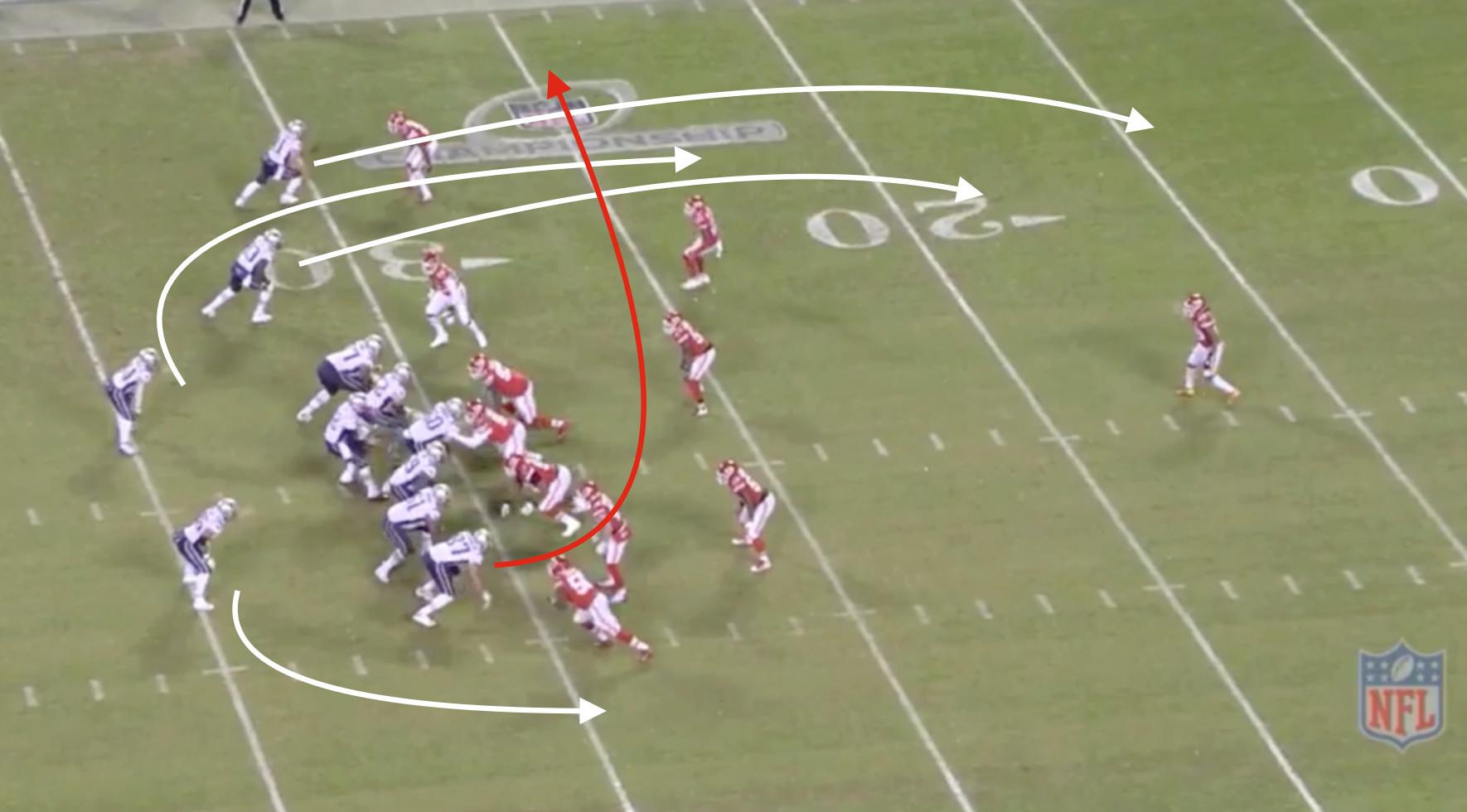

Gronk was a big part of the game plan as well, seeing a season-high 11 targets while catching six passes for 79 yards—easily his best output in over a month. On this second-quarter play, he was Brady’s trusty outlet option. Brady sent Burkhead out to the wing before the snap, and when the corner bumped outside on the running back it signaled that the Chiefs were likely in a zone-coverage scheme. Allen ran a vertical route up the seam from the right side of the line, Develin leaked out to the left side, and Gronk ran a short drag across the formation.

As the middle linebacker focused on Allen, Brady saw quickly that Gronk was the place to go. Easy money.

Brady found Gronkowski again in the fourth quarter, this time against apparent man coverage. After motioning across the formation presnap, Allen, Edelman, and Burkhead all ran clear-out routes up the numbers in the hopes of pulling all the defenders on that side of the ball deep down the field. Gronk simply ran a crossing route underneath, with a defender trailing in coverage.

Linebacker Anthony Hitchens briefly stuck with Burkhead before realizing the pass was to Gronk, but he sniffed it out too late. Gronk beat Hitchens around the corner, avoided the tackle, and picked up some extra yards.

The ability to use motion to first identify coverage and then attack it came in handy in the overtime period too. Brady converted three straight third-and-10 plays to lead New England down the field and score the game-winning touchdown—but for most of the first four quarters, the team really didn’t need those types of heroics. Brady hit on a few key chunk plays, but on the whole, the Patriots were content to simply matriculate their way down the field, mounting separate drives of 15 plays, 11 plays, nine plays, 10 plays, and 13 plays.

A dominant run game and Brady’s mastery of coverages consistently allowed the Patriots to be in manageable third-down situations (they averaged 5.32 yards to go on third down, lowest among teams in the championship round, and converted 13 of 19), control the ball (they ran 94 plays, most in a playoff game since the 1986 season), and bleed the clock (they possessed the ball for more than 43 minutes, more than double the Chiefs). Most important, though, was the Patriots’ ability to keep Brady upright. The Chiefs never really got close to hitting the 41-year-old signal-caller, either; they simply didn’t have time. The combination of Brady’s lightning-fast processing skills and McDaniels’s brilliant scheming meant that the ball was almost always out before K.C. could break through the line. After averaging a divisional-round low of 2.33 seconds to throw against the Chargers, Brady again clocked in with the quickest release in the championship round, averaging 2.51 seconds per throw.

That quick game will come into play in Super Bowl LIII. The Patriots handled the the Chargers’ and Chiefs’ pass rush units, but New England has its work cut out for it against the Rams’ unique pass-rushing front. With a pair of interior playmakers in Aaron Donald and Ndamukong Suh, L.A. destroyed opposing pockets with regularity this year. And, on paper, they look prepared to do what the Chargers and Chiefs could not. L.A. posted a league-best 16.6 percent pressure rate from the inside this year, a strength that could be the key to solving New England’s so-far-bulletproof postseason strategy: Brady’s passer rating against edge pressure this year, including the playoffs, is an astounding 118.7, but when facing interior pressure, it drops to just 63.1.

New England’s got the weapons, the tactics, and the quarterback needed to combat the Rams’ premier interior pass-rush duo, though. It may mix in new plays and vary the use of personnel to try to keep L.A. on its heels, but I expect the game plan won’t change drastically: The Pats will try to run it down the Rams’ throats, and Brady will try to feast on plays that get the ball out of his hands in two and a half seconds or less. We’ll find out whether that’s enough time to keep Suh and Donald at bay.