The World According to Ray Ratto

The longtime Bay Area sportswriter doesn’t believe his business had a golden age. (“The good old days were way shittier than the days now.”) Nor does he have any time for journalism awards. (“If this matters to you, you fucked up.”) Insult has been his professional stock-in-trade, and his recent unemployment will not change that.Something awful happened to Ray Ratto. It isn’t that he lost his job. It’s worse than that: A lot of people have been telling Ratto how much they like him.

Ratto’s sportswriting stock-in-trade is the insult. Praise makes him suspicious. “I think when you want to say something nice about somebody, it should be private,” Ratto told me. “When you want to say something shitty, everybody should see it.”

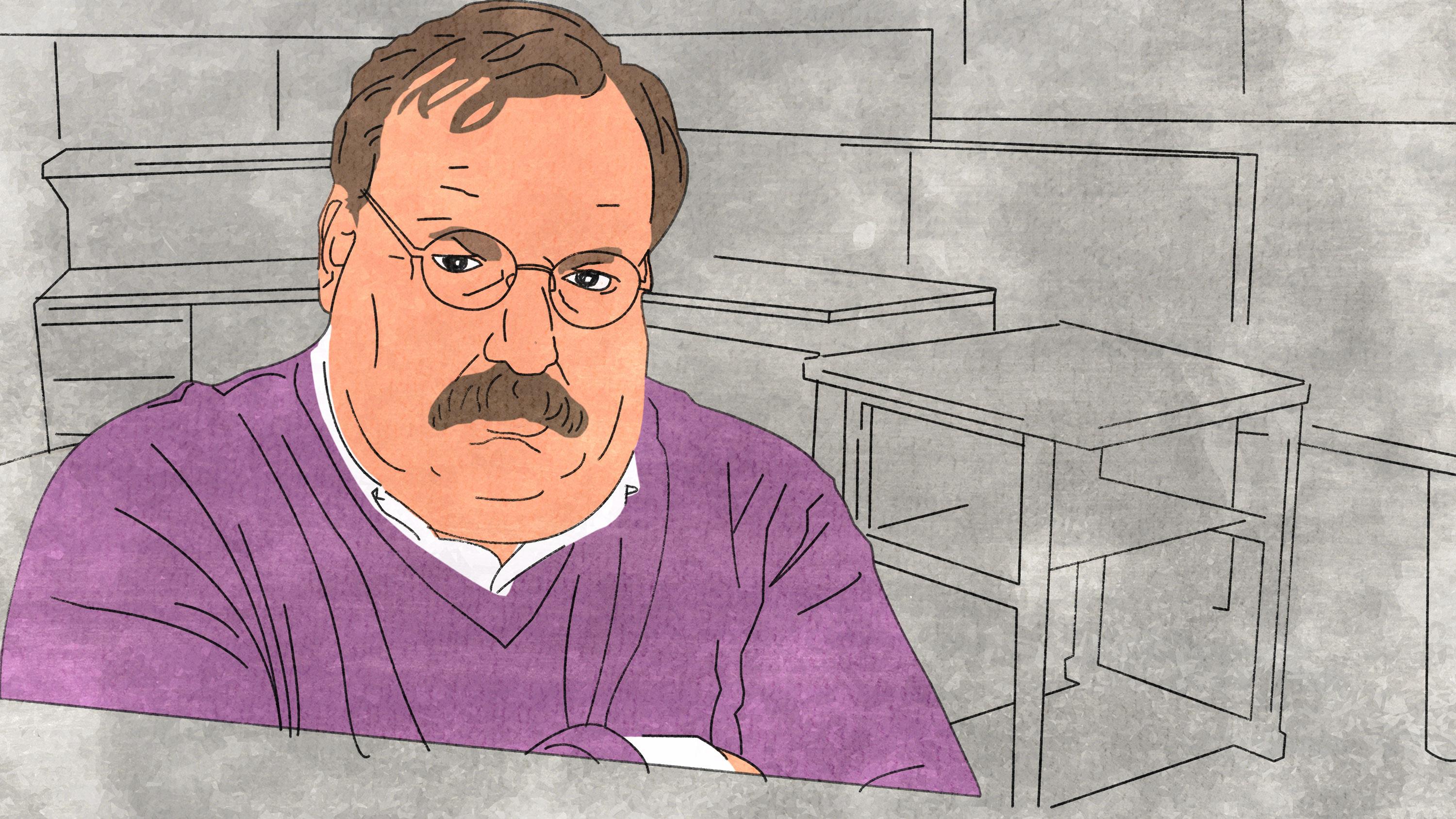

It was a rainy day last week, and Ratto and I were having lunch at an Oakland café. He had sauntered in and pulled off his jacket to reveal a red, white, and blue–striped specimen from what his old boss Glenn Schwarz calls his “vast ugly-sweater collection.” Ratto is one of the few sports columnists who wore a sweater in his author photo rather than a coat and tie.

“I’m up to my ass in free time,” Ratto said. “I’ve got more free time than the planet can allow!”

Ratto, who’d been a writer and TV guy for NBC Sports Bay Area since 2010, was told late last year his services were no longer needed. “I don’t know what the answer is for them,” Ratto said. “They concluded that I’m not the answer. So ...” It’s the first time he has been out of work since The National combusted in 1991—and then he got a column at The San Francisco Examiner within hours.

Ratto said: “When The National folded, everybody said the same thing: ‘You’ll be fine, you’ll be fine.’ I was fine, but I knew a lot of people who worked there who never were fine again. They either scuffled or they got out of the business. There’s no landing on your feet. You’re either lucky or not. Last time, I was lucky. This time, I might not be.”

Ratto fans who followed him in both major San Francisco newspapers or on Twitter will understand that a particular kind of literary vehicle is in danger. Call it the Ratto-ism. A Ratto-ism is a remark that is oddly angled, slightly to extremely insulting, and close enough to inappropriate that the refs will call for a measurement.

Ratto on his literary process: “When I start to get stale, I try to figure out a different way to write the same old crap.”

Ratto on his job prospects: “Opportunity is not going to put its tongue down my throat that often.”

Ratto on his philosophy of life: “Drink to excess, and end up with a profile like Alfred Hitchcock’s. Avoid people. Those you can’t avoid, assume they are going to steal from you. And never give your real name.”

A few years back, I wanted to meet Ratto in the Warriors’ press room so I could enrich a story I was writing with a Ratto-ism. Ratto replied by DM: “Let us gather over a wilted salad and a meal made of neglect and hate.”

This month, I proposed another meal. On the occasion of Ratto’s unemployment, I wanted to try to distill his essence—his tao. Ratto replied: “Congratulations for discovering The End Of Ideas.”

It’s possible to appreciate Ratto purely through these malignant exteriors. Ratto types his columns—this is not a joke—with his two middle fingers. “Put it this way,” said Will Clark, the Giants first baseman whom Ratto covered as a beat man. “His personality shone through in his writing.”

I always thought Ratto’s insults—like those of other writers who work with bone saws, Drew Magary, say—could be arranged to form a moral code of sportswriting. It was as if Ratto was suggesting how we ought to carry ourselves in this “scam” (his word) and about what things we ought to find important.

Ratto resists such analysis. “Nobody’s saving anything that I wrote—ever,” he said. But give him some red wine, and he begins to share his philosophy. Referring to his sweaters, Ratto said: “When [a sportswriter] comes to games in a suit and tie, you say, ‘Who are you trying to impress? What kind of overstuffed asshole are you?’”

“We should aggressively not look like Jimmy Cannon,” he continued. “We do not lend more dignity to an event that is essentially built on being undignified.”

Ah, yes. There we go. Now we’re moving closer to the tao of Ratto.

Ratto is the kind of big-city sports columnist who used to exist everywhere and now barely exists anywhere. He was born in Oakland in 1954, and he never left the area. Today, he lives about 15 blocks from where his grandfather, an Italian immigrant named Benedetto Ratto, had a vegetable farm.

Ratto related this family history without a trace of wistfulness. In fact, he suggested I look up his surname in an Italian dictionary. It means “abduction” or “rape.”

By age 19, Ratto was a wiseass copy boy at the Examiner. “A guy who taught me a lot about this scam,” he said, “was a guy named Nick Peters, who just passed. One of the first times I was ever in a clubhouse, I at least had the wisdom to go up and say, ‘So how do you do this and do it well?’ He said, ‘Never show fear.’”

Young Ratto was interviewing Giants manager Frank Robinson for a story. Robinson blew him off with a couple of short answers. Ratto recalled: “I finally said, ‘Well, look, if you don’t want to do this, let’s just not do it.’ And I got up and walked out. He said, ‘C’mere!’ I said, ‘Yeah?’ He said, ‘What do you want to know?’”

Peters later told Ratto: “He wanted to see if you were going to shit yourself.”

The same might be said for Ratto when he cheerfully insults his colleagues. Ratto likes insults so much he has shared them with the world in at least three different outlets. Most people know the insults from Twitter or his column. But in the ’80s, Ratto was writing a fantasy football newsletter that tweaked his Examiner colleagues. When Ratto learned other sportswriters were reading copies of the newsletter, samizdat-style, he made sure he also insulted them. “I felt like I’d won the Pulitzer when I made it,” said John Schulian, who wrote for the Chicago Daily News.

That’s the thing about Ratto insults: Sportswriters value them, even if they fear they can never answer them. A Ratto insult means that he likes you. “One of my favorites,” said The Athletic writer Daniel Brown, “was when I walked past his computer in the press box—this was years ago—and noticed he had Bad Santa on.

“He said, ‘It’s one of my favorites.’

“I said, ‘Oh, what a surprise. It’s about an overweight, cynical smartass who gets the girl.’

“I said it quietly. He responds loudly for the press box, ‘Why don’t you shut up and go back to being afraid of your wife?’” (Brown is married to Susan Slusser, of the San Francisco Chronicle.)

Ratto does some of his best—which is to say, most lethal—work when a local sportswriter is honored with an award. Most of the writer’s colleagues get up at the party to share some compliments. “He turns it into a roast,” said Brown. “Sometimes there’s a softness to it, but not always. It brings the house down every time.”

In Ratto’s column, his affect is less wiseass than wised-up. It’s as if he’s telling everyone: We all know what’s going on here, and I’m the guy who’s going to say it. “If he was lighting your ass up, it would piss you off,” said former Giants pitcher Mike Krukow, who’s now an announcer. “But it would still be pretty funny. You’d get to the ballpark and teammates would be quoting what he said about you.”

Ratto on the opening of San Francisco’s Pacific Bell (now Oracle) Park: “And so, after three years of schmoozing, begging, and tub-thumping, after six weeks of relentless media greasing and after a teeth-grinding half-hour pregame ceremony and self-congratu-fest that would have broken even the most hardened criminal into a sobbing confession…”

Ratto on the NCAA: “The Association defends its trademark prerogatives down to the last soda cup with an almost Serbian zeal.”

Ratto on an NFL Sunday: “Forty Niners–Bucs at 10, Jets-Raiders at 1:30. As for church, family obligations, or just lifting your bloated and ever-widening seater off the couch, you’re on your own.”

Once, the Chronicle sent Ratto to cover a meaningless late-season Oakland A’s game. It was an NFL Sunday, so the story was going to run inside the section. Ratto’s gamer began thusly: “Meanwhile, back here among the tire ads …”

When you read Ratto’s column, you can feel him trying very hard to be original. By sports-page standards, he writes long sentences, and his prose is ornate in a hard-boiled sort of way. “I think there’s a certain demographic that has no chance of deciphering the genius of it,” said Brown. “I don’t want to say he’s an acquired taste. But it requires some sophistication. You can’t be a dimwit and read that.”

Ratto tries so hard to be Ratto that he has lost out on some attaboys and sportswriting awards he might’ve otherwise collected. But as he told me: “Everything about an award in my mind says, ‘If this matters to you, you fucked up.’”

Ratto’s friends suggest that a slightly different creature lurks beneath the insults. “He puts up, I think, defenses sometimes that are intended to make sure people don’t see the real guy underneath,” said Tim Keown, a writer with ESPN the Magazine.

“I’m sure people have suggested to you that there’s a ‘Rat’ and a ‘Ray’ out there,” said Mark Fainaru-Wada, a Chronicle ex who now works for ESPN. “The Rat is the personality that has those contrarian, sardonic, cantankerous qualities when he writes and speaks.

“Then there’s Ray. In the right moment, though he’ll never admit it, he’s a loveable figure who is a really good human being—who will chastise me for even having said this.”

You can see glimpses of this in Ratto’s professional moral code. Some of it’s easy to discern. Ratto can be a sneaky mensch: Read his obit for the announcer Bill King (written in under an hour) to see how he creates emotion through the brain, not the tear ducts.

Ratto is the rare member of the sports-page generation who recognizes there are equal pleasures to be found in the age of newspapers and the age of blogging. “The trick to me was, don’t pander to a generation you’re not a member of,” Ratto said. “But don’t act like the cranky old bastard, either, who wants to talk about the ‘good old days.’ Because for the most part, the good old days were way shittier than the days now.”

For a guy who loudly chews scenery, Ratto is oddly modest. In his writing, he doesn’t use the pronoun “I.” He uses “we.” Several times, he questioned why he deserved a profile at all.

Ratto’s modesty leads him to question what a sportswriter can really understand about a ballplayer. “We don’t know who these guys are,” he said. “So let’s not be making judgments about their character based on whether we like ’em or not. That’s why I didn’t get all hung up on ‘Barry Bonds is an asshole.’ Yeah, OK. I’m not covering him for his deportment.”

Dieter Kurtenbach, a San Jose Mercury News columnist and Ratto acolyte, said: “He could absolutely be like, ‘Motherfuckers, I’ve been around here for 10 times longer than anybody else. That picture with Dwight Clark? That’s me. I’ve seen real estate prices go up 40 times over. If I say something, it’s goddamn gospel.’ But you’ll never get him to say that, and he doesn’t believe it.”

Maybe most interestingly, Ratto makes the case for writerly grumpiness. “Ratto in the Chronicle was always the best sort of cranky,” said Tommy Craggs, who did a tour at SF Weekly. “He was cranky at the right time, which was always, and he was cranky about the right people, which in my memory was everyone in charge.” In 2004, watch how Ratto imagined and then answered a quote from A’s owner Steve Schott after the A’s traded away pitcher Mark Mulder:

We’re a small-market team (which the A’s absolutely are not), and we have to make hard choices (which are different in many ways from suicidally stupid ones) and we really regret having to trade Mark (which they absolutely do not regret at all) but those are the conditions that prevail (yeah, when you’re squeezing those quarters so hard that George Washington wishes Cornwallis had shown a little more gumption).

Schwarz, a former Chronicle sports editor, used to tease Ratto that it pained him when local teams won; for a time, Ratto wrote a column called “The Miserablist.” “That’s the way we view him,” said Tom Tolbert, Ratto’s former radio partner at KNBR. “But I’m not sure he sees himself that way. I think he sees himself as reality—not how it could be or would be but how it is.”

You could put this in a slightly different way. If Ratto’s tone is extravagantly curmudgeonly, it has the effect of making the overweening cynicism of sports somewhat more bearable.

“He just sees himself as some guy who cracks wise about sports and doesn’t realize a lot of people really love him,” said Keown. “He’s part of their life, especially in the Bay Area.”

Ratto and I finished our lunch and drained three glasses of wine. Then the man behind the bar brought over two fresh glasses of cabernet. They were on the house, the man said, for he was a huge fan of Ratto’s.

“Give it time,” Ratto said. “That’ll blow over.”

On January 2, Ratto watched his professional funeral pyre with mild terror—all these people he’d insulted telling him how they couldn’t wait for him to write again. My favorite tweet came from ESPN’s Don Van Natta Jr., who posted a tribute while noting Ratto “doesn’t like me very much.”

Ratto insists he’ll be OK if he doesn’t get another column. “Only because the nature of the business is changing,” he said, “so there are fewer and fewer jobs that you can feel good about. More and more jobs are connected to companies that have interest in teams or leagues. Now, all of a sudden, you have to figure out, Well, how much of a whore are they going to ask me to be?”

“I can’t all of a sudden become a shill,” Ratto said. “That’s not who I think people perceive me as. I think people perceive me as the sort of person you would immigrate to avoid.”

After talking to him, I think Ratto views his unemployment the same way he’d view a column about a lovable, 10-year Major League vet who got released at the end of spring training: a guy who, in a happier world, would have gotten to walk away on his own a season or two later.

“Nobody wants to hear you bitch about the fact that you had a great job for 40 years,” he said, “and now you don’t get like the last 18 months. Yeah, your life sucks. Fuck you! Shut up! I’m lifting pallets of Dinty Moore at Costco midnight to 8:00! I don’t want to hear your sad tale! Because there really isn’t one. I still want to do something. But like I said, that’s up to the gods.”

A few hours after our lunch, Ratto DMed me to say: “That was fucking weird.”

But I was already thinking about another Ratto-ism. “Would I have liked to be some douchebag big deal?” Ratto said. “It would have been fun for a while. But I am what I am. So fuck it.” That’s it, sports fans. That’s the tao of Ratto.