Even in an undertaking as trivial as baseball, entrenched institutions often struggle to adapt to a changing world. Over the past 20 years, the writers and historians—to say nothing of the fans—who chronicle the sport have been divided over numerous issues: most notably how players ought to be evaluated in the wake of the sabermetric revolution, and how to reckon with the influence of performance-enhancing drugs. In the face of this division, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum has emerged not just as the historical and literary nerve center of the sport, but as a revanchist force in the culture war.

As fans and analysts alike have come to understand sabermetrics and grapple with its history of PED use, the Hall of Fame has resisted efforts at reform, rejecting the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s recommendation to make all Hall of Fame ballots public. In response to an increasingly sabermetrically savvy electorate, the Hall of Fame has used closed-door select committees to induct candidates the writers deemed unworthy for enshrinement. (Admittedly, committee cronyism is nothing new in Cooperstown—under the Veterans Committee of the 1960s, everyone with former Giants and Cardinals second baseman, and Veterans Committee member, Frankie Frisch’s home phone number got into the Hall.)

And as the writers sort out for themselves what to do with players linked to PEDs, Hall of Fame board member Joe Morgan fills his time sending out a harangue telling voters that steroid users of the 1990s and 2000s are unworthy. (The letter, curiously, does not include a moral judgment on the use of amphetamines, which were common in MLB clubhouses during Morgan’s playing career.)

The struggle over how to write baseball history is ongoing, but the BBWAA’s class of 2019 signals that it’s at least reached a turning point. Mariano Rivera became the first unanimous inductee in the history of the Hall of Fame, appearing on all 425 ballots. Roy Halladay and Edgar Martínez both appeared on 85.4 percent of the ballots, while Mike Mussina, in his sixth appearance on the ballot, got 76.7 percent of the vote, just over the 75 percent threshold for induction. Each player in this class represents some aspect of how the game in 2019 has changed from how we understood it even 20 years ago, let alone in Morgan’s heyday.

It’s difficult to compare pitchers across eras, not just because things like park effects and competition change, but because the way pitchers are used has changed so much. We’re at the pointy end of a 150-year trend of pitchers evolving to throw harder over fewer innings, which makes it tough to compare Walter Johnson’s 350-inning workloads to, say, Clayton Kershaw’s 210-inning workloads. We can’t use 300 wins as a benchmark anymore, because nobody starts enough games to get there. Even 3,000 strikeouts is losing its meaning, because someone like Pedro Martínez can strike out 3,000 batters in about half as many innings pitched as Johnson needed to reach the same milestone 80 years before.

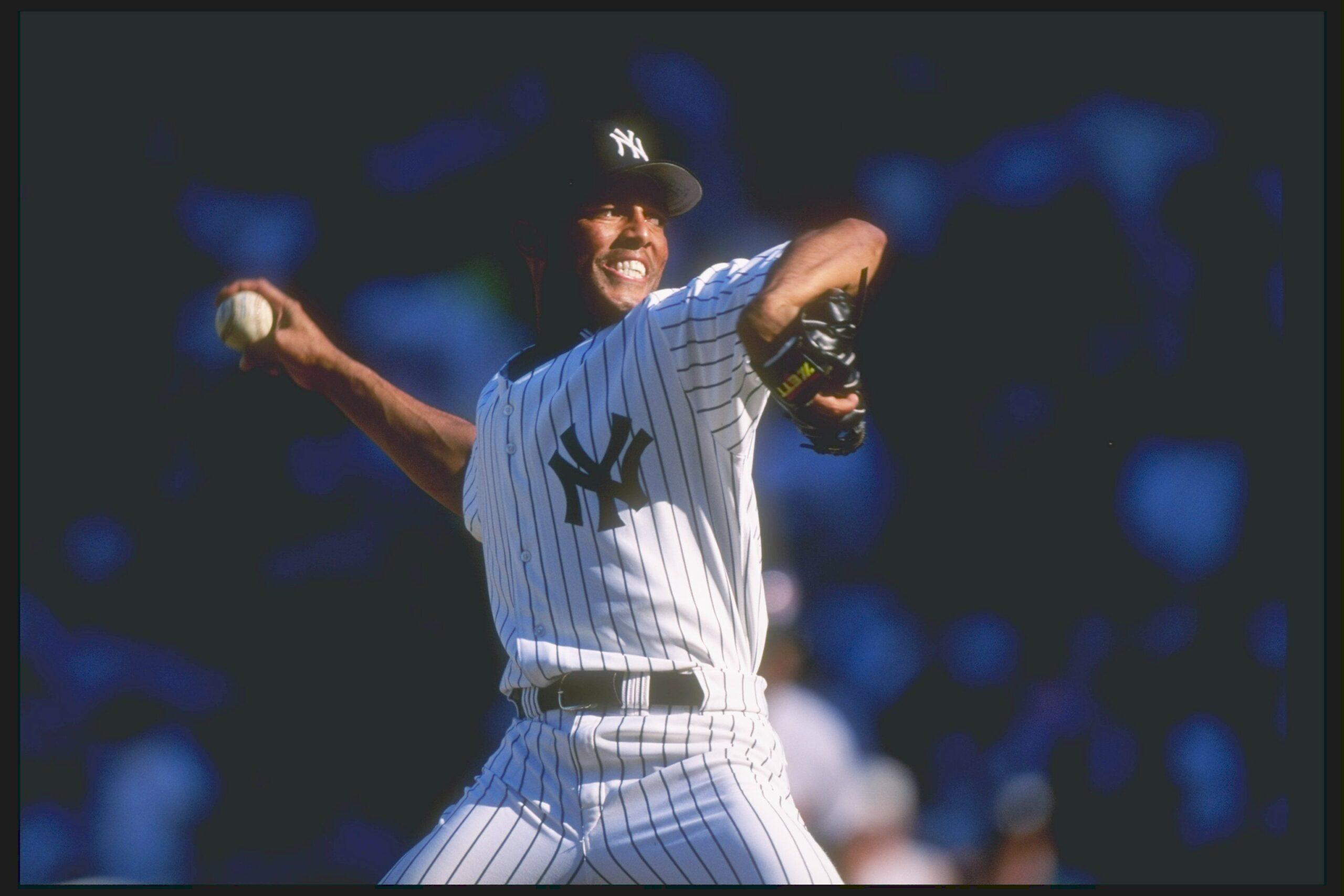

The ultimate end to this evolution is the one-inning closer, of which Rivera is the greatest example. The saying goes that all great relievers are failed starters, and Rivera is no different—in 1995, he posted a 5.51 ERA in 10 starts and nine relief appearances as a 25-year-old rookie. It’s something of a miracle that Rivera went on to become a Hall of Famer after that. Since integration, only four Hall of Fame pitchers have made their MLB debuts as late as their age-25 season: knuckleballers Phil Niekro and Hoyt Wilhelm, Rivera, and Trevor Hoffman. (Hoffman and Rivera, the two members of the 600-save club, both pitched in the big leagues for the first time when they were 25 years and 175 days old.)

In 1996, Rivera had turned into a dominant multi-inning setup man, posting a 240 ERA+ over 107 2/3 innings, and in 1997, he became the Yankees’ closer, a post he held for the next 17 seasons. Rivera is the all-time leader in saves (652) and games finished (952), made 13 All-Star teams, and finished in the top five in Cy Young voting five times. Rivera has a career ERA+ of 205 in 1,283 2/3 innings pitched—among pitchers with at least 1,000 career innings since 1901, only Rivera, Martínez, and Clayton Kershaw have a career ERA+ of better than 150.

Despite getting such a late start, and despite building his career in mostly one-inning increments, Rivera’s regular-season accomplishments are most impressive in volume. There’s an argument that closers don’t pitch enough innings to be truly impactful, or that like Rivera, most arrive in the bullpen only because they couldn’t hack it in the rotation. But Rivera was such a good closer, and for so long, that his career bWAR (56.3), a leverage-neutral counting stat, is higher than that of 17 Hall of Fame starting pitchers, including Sandy Koufax and Whitey Ford. Rivera at his best wasn’t light-years better than Billy Wagner at his best, or Jonathan Papelbon or Craig Kimbrel. What sets Rivera apart is that he was consistently superb at a supremely volatile position, that his peak lasted through Wagner’s peak, then Papelbon’s, and into Kimbrel’s. No other reliever in baseball history can claim such a sustained period of excellence.

Any evaluation of Rivera’s Hall of Fame credentials must also include his postseason accomplishments. Rivera is one of few contemporary players whose indelible image isn’t necessarily statistical. Sure, he’s the all-time leader in postseason ERA (0.70 in 141 innings) and saves (42—the next three pitchers on the last, Brad Lidge, Kenley Jansen, and Dennis Eckersley, have 49 career playoff saves put together). But Rivera was the victory cigar for Yankees teams that won seven pennants and five World Series. Judging a career on postseason success is tricky, because it’s predicated on opportunity and based in small sample sizes. But Rivera was so good for so long that his postseason exploits burnish his credentials in a way that no other player can claim, perhaps in all of baseball history.

At the 2008 American League All-Star Game, Rivera sat down with Toronto Blue Jays right-hander Roy Halladay, who’d been struggling to throw his cutter consistently. There was nobody better to ask—Rivera famously threw his cutter almost exclusively, while Halladay, the 2003 AL Cy Young winner, used his cutter as just one of his five pitches. Rivera showed Halladay how to position his fingers, and the big right-hander beat the Yankees three times in the second half, earning Rivera a fine in kangaroo court.

Halladay’s induction to the Hall of Fame will be bittersweet, as the former Blue Jays and Phillies ace died in a plane crash at age 40 in November 2017. But he’s not merely a sentimental favorite—Halladay was, for a time, the best pitcher in baseball, and more than deserving of a spot in Cooperstown, despite a relatively short career for a pitcher of his historical stature. After reaching the majors at 21, Halladay took some time to mature into the pitcher he became—in 2000, the 23-year-old Halladay posted a 10.64 ERA in 67 innings, which makes him the first Hall of Famer to post a full-season ERA over 10 in at least 60 innings. The details of Halladay’s resurgence, best chronicled in this 2010 Sports Illustrated cover story by Tom Verducci, have become their own legend, but by 2002 Halladay had remade himself into an All Star.

While Rivera spread relatively few innings across many seasons, Halladay crammed all his achievements and accolades into his 10-year peak, in which he made eight All-Star teams, won two Cy Youngs (one in each league), and finished in the top five in Cy Young voting five more times. Halladay never led the league in strikeouts and only once (in 2011) led the league in ERA+, but he weaponized volume in a way no other pitcher of his era did. Halladay led the league in complete games seven times and shutouts four times; in 2009 and 2010 he threw four complete-game shutouts each year, a mark nobody’s reached since 2012. No pitcher has thrown more than 260 innings in a season since Halladay’s first Cy Young season in 2003; Halladay went over 250 innings in his second Cy Young season in 2010, a mark that’s been matched only once since. That volume is reflected in his counting stats: From 2002 to 2011, Halladay posted 62.6 bWAR. Second place among pitchers in that span was Johan Santana, at 50.4.

Halladay’s combination of excellence and volume fits with him aesthetically. Compared to the spindly and precise Rivera, Halladay loomed over hitters, joints crooked like the seams on a folded parachute, ready to spring out and smother hitters. His greatest single-game achievements—his perfect game against the Marlins and his playoff no-hitter against the Reds, both in 2010—were testaments to Halladay’s inexorability. He could outlast his opponents within a game and a season in a way no pitcher really has since.

But because Halladay’s prime was so short—nagging shoulder injuries ended his prime at 34 and his career at 36—Halladay’s career is a statistical blueprint for what a Hall of Fame starting pitcher looks like in the 2010s. He threw just 2,749 1/3 innings in his career. Only four Hall of Fame starters have thrown fewer: Lefty Gomez, Addie Joss, Sandy Koufax, and Dizzy Dean. Joss died of tuberculosis just after turning 31, while Gomez, Koufax, and Dean all suffered essentially career-ending injuries around the same age. These four pitchers were top-of-the-line starters whose careers were shortened (on an innings basis) by injury or illness; modern top-end starters have had their careers shortened by the evolution of the game.

Like Koufax and Dean, Halladay was the best pitcher in baseball not just because of his great rate stats but because of his volume of innings—250 innings in 2003 was like 320 innings in 1966—and was showered with awards by the contemporary media. In fact, Dean, Koufax, and Halladay all have the exact same career ERA+: 131. This group of inductees shows that the Hall of Fame already has a place for starting pitchers who posted spectacular careers in limited innings.

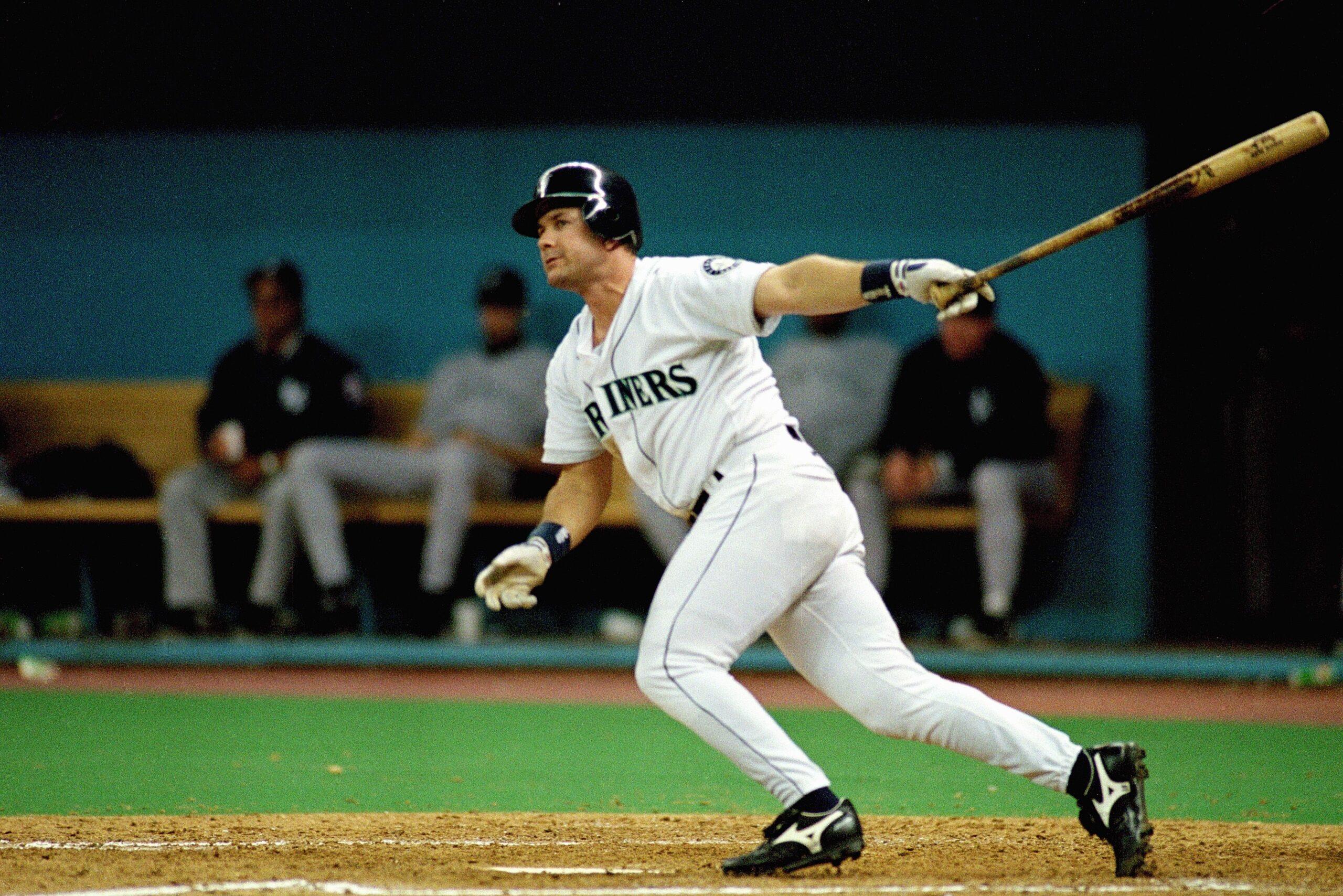

While Halladay and Rivera have been inducted in their first year of eligibility, Martínez has waited a decade for his turn at Cooperstown, finally breaking across the line on his 10th and final turn on the ballot. Martínez was also a late bloomer, not reaching the majors until 24 and not qualifying for a batting title until 1990, his age-27 campaign. From there, Martínez forged a career that looked solid at the time and became remarkable only in retrospect.

In addition to being overshadowed by more famous teammates like Ken Griffey Jr., Randy Johnson, and Alex Rodriguez, Martínez’s offensive profile made him easy to overlook by traditional metrics. Even with two batting titles, a career .312 batting average, and seven All-Star appearances, Martínez didn’t stand out at a position where he was expected to hit for more power. Martínez led the league in RBIs once and doubles twice, but posted just one 30-homer season and 309 home runs for his entire career. These looked like Hall of Very Good numbers for a player who contributed only with his bat and didn’t reach 3,000 hits.

It took a post-Moneyball outlook on baseball to truly appreciate Martínez, namely that he was outrageously good at avoiding outs. His .418 career OBP is the fourth-highest mark of the past 50 years, and he retired with a higher career SLG (.515) than Reggie Jackson and Harmon Killebrew, both of whom hit more than 500 home runs in their careers.

But the biggest discussion point regarding Martínez was the weird hangup on his being a career DH. Never mind that certain Hall of Famers would probably have been more valuable to their teams not playing the field at all—Willie Stargell’s career minus-19.5 defensive WAR comes to mind—but the BBWAA has already elected Frank Thomas, who played more career games at DH than first base. This year the Today’s Game committee legitimized the DH as a Hall of Fame candidate by inducting Harold Baines, a contemporary of Martínez’s who played 1,643 games at DH and whose career offensive numbers pale in comparison to Martínez’s. These precedents, plus a final-year voting surge like the one that put Tim Raines in the hall two years ago, were enough to finally put Martínez over the top.

It’s also worth noting that Martínez’s induction was likely delayed by the BBWAA electorate’s intense but short-lived antipathy toward players from the 1990s. As a significant faction of writers (and the league and Hall of Fame itself) belatedly denounced the cartoonishly muscled players whose achievements they feted 20 years ago, it created a backlog on the ballot. Players named in the Mitchell Report, like Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, were out, no matter what their accomplishments, as were players like Rafael Palmeiro and Manny Ramírez, who put up Hall of Fame numbers but tested positive for PEDs. Then there were players who had never been credibly charged with PED use but just looked too muscular, like Jeff Bagwell, who waited seven years on the ballot before being inducted. Even players like Martínez, who had no links to steroids or PEDs, got caught in the crossfire, either by hardline voters who wrote off an entire generation of players, or just because they faced more competition for votes than the system was designed to handle.

BBWAA members are allowed to vote for only 10 candidates per year, which means that if players with first-ballot numbers don’t get voted in on the first ballot, the ballot gets crowded. In some years, as many as 20 players with a legitimate Hall of Fame case would end up on the ballot at the same time, and there wasn’t room for everyone to vote for Raines and Martínez and Larry Walker, and so on.

So Hall of Fame candidates with no PED history to speak of would end up as collateral damage. Players like Martínez, or the fourth inductee, Mike Mussina.

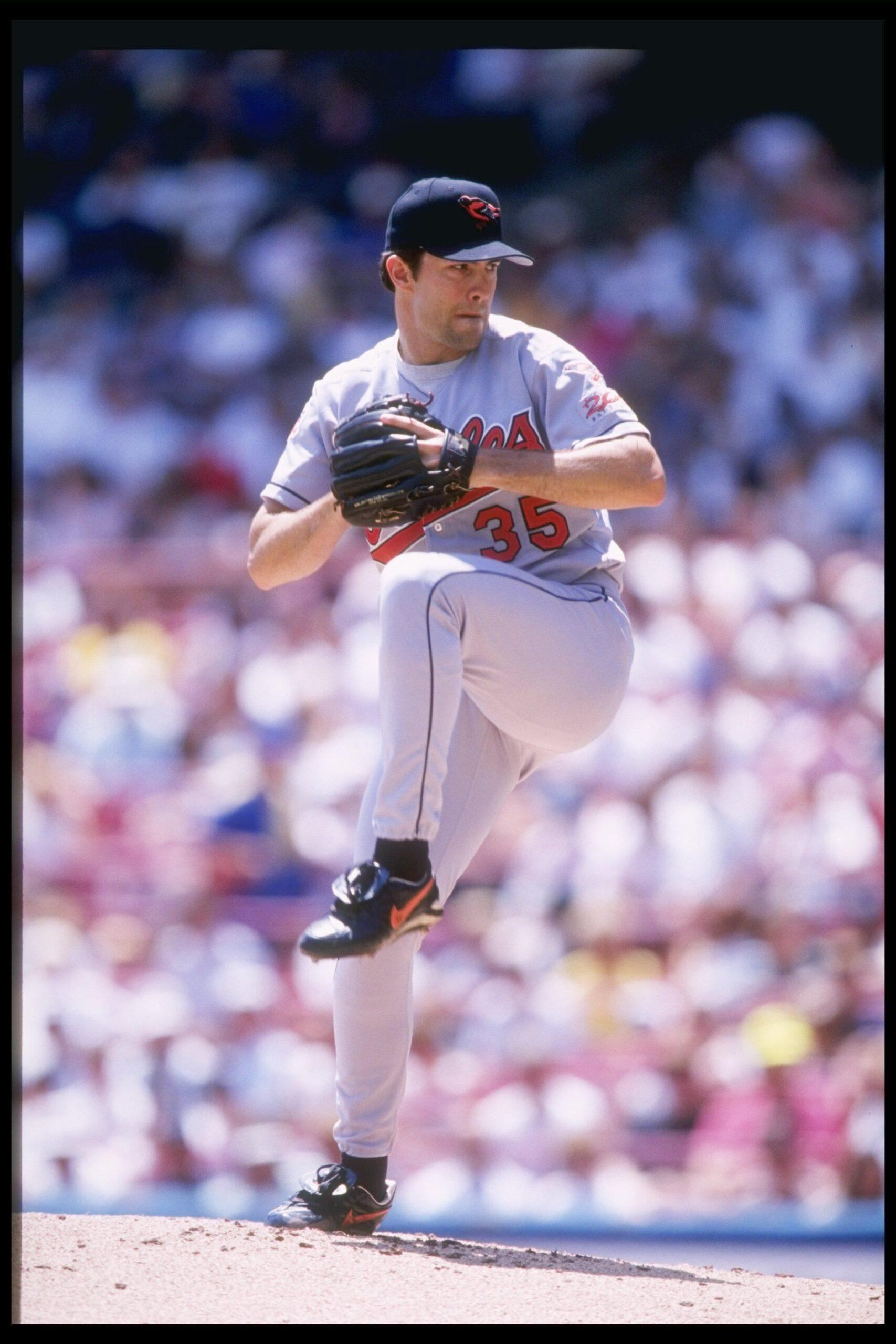

Mussina, elected here on his sixth appearance on the ballot, really shouldn’t have been a dramatic selection. He didn’t play a controversial position like Martínez or Rivera, nor did his career end early like Halladay’s. Mussina’s 270 wins play in any era. Only three other pitchers since 1900 have won more games and not made it to Cooperstown: lefties Jim Kaat and Tommy John, neither of whom was anywhere near as good as Mussina at his peak, and Roger Clemens, who might be the best pitcher ever but whose PED history continues to keep him out of the Hall of Fame. Ditto Mussina’s 2,813 career strikeouts, which only four non–Hall of Fame pitchers can beat: Clemens; Mickey Lolich, whose career is similar to John’s or Kaat’s; CC Sabathia, who’s still active; and Curt Schilling, who’s partially a victim of the same forces that had kept Mussina out, but also struggling with voters for reasons of his own making.

Mussina posted a 139 ERA+ in 12 starts as a 22-year-old rookie in 1991, and posted a 131 ERA+ in 34 starts in his final season, 2008. In between he made five All-Star teams and posted 82.9 career bWAR. The two drags on Mussina’s résumé—which, it bears repeating, is good enough for the Hall of Fame with room to spare—are the lack of a World Series title and the lack of a Cy Young.

The first is the result of almost comical bad luck—Mussina pitched well in the postseason throughout his career, with a 3.42 ERA and 145 strikeouts in 139 2/3 innings across 23 appearances in nine different years. In the 1997 ALCS, for instance, Mussina made two starts: In the first, he allowed one run and struck out 15 in seven innings, and his Orioles lost in extra innings. In the second, he threw eight innings of one-hit shutout ball, and the Orioles lost in extra innings again. When Mussina hit free agency after the 2000 season, he joined the Yankees, who had won that year’s World Series and four of the past five. Mussina pitched eight seasons in New York, appeared in two World Series, both Yankee losses, and retired in 2008. The Yankees won the World Series again a year later.

The lack of a Cy Young, meanwhile, would indicate that Mussina was never the best pitcher in the American League, and that’s probably true. But considering that his best years overlapped with Cy Young seasons from Clemens, Johnson, Pedro Martínez, and Halladay, holding that against him seems unjustly harsh.

After years of confusion and infighting, the BBWAA has elected multiple candidates in six straight years—every year since the infamous empty class of 2013. That’s thinned out the crop of candidates substantially, and ballot reform, the evolution of the electorate, and the mere passage of time have allowed voters and fans to once again approach a consensus on what constitutes a Hall of Famer—even the PED stigma is waning. This class reinforces emerging precedents in terms of position and career length, and is helping to clear out the backlog so the next generation of candidates faces a fairer ballot. That’s good news not only for the inductees and candidates, but for voters, fans, and the Hall of Fame itself, for which large classes means large crowds come induction weekend. Between labor strife, issues of competitive balance, and the ongoing concern-trolling about the evolution of the game, it’s tough to remember what substantial success for all of baseball’s stakeholders looks like, but this is it.