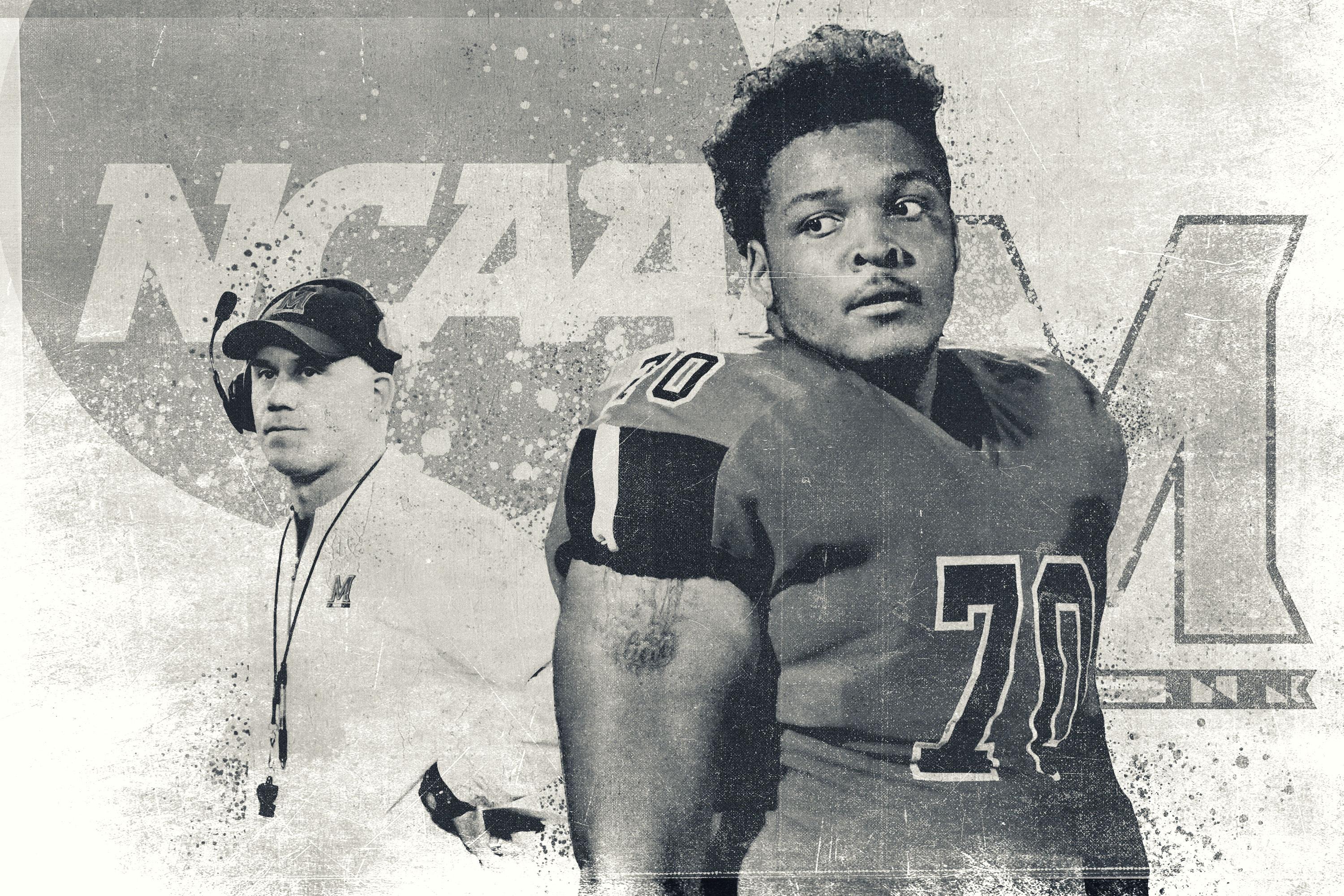

Don’t Forget Jordan McNair

As another college football season fades into a sea of confetti and celebration, we owe it to ourselves, the institutions we cheer for, and the hideous history of players dying while playing college football to remember the tragedy that occurred at Maryland last year and to demand change

The afternoon of May 29, 2018, should have been painless. Jordan McNair, a 19-year-old offensive lineman for the Maryland Terrapins, began running around 4:15 p.m. Within 45 minutes of sprinting 110 yards several times, his body seized. McNair collapsed. Teammates helped him finish the drills, slogging through the heat on a sweltering afternoon. “Drag his ass across the field!” Wes Robinson, Maryland’s head athletic trainer, reportedly said. No one understood that the boy was dying.

The McNair family’s attorney said an “unexplained” hour passed between the family’s son’s seizure and a 911 call that an unknown man placed at 5:58 p.m. McNair didn’t reach a hospital until 6:36 p.m., at which point he was in critical but stable condition. His body burned at 106 degrees. An unnamed Maryland coach told medical responders that McNair was breathing oddly and hyperventilating after he collapsed. Yet trainers didn’t take his temperature or assess his vital signs. Recalling this in an August television interview, his mother, Tonya Wilson, cried.

“No one did anything to even try and cool him down,” Wilson said. “That’s the part that bothers me most. There was nothing I could do. And I couldn’t help him. It breaks my heart.”

McNair slipped into a coma and died two weeks after he was hospitalized. “There was no regard,” Wilson said of Maryland. “They just didn’t care.”

As fans bask in the thrill that college football can create following Clemson’s rousing national championship victory on Monday night, it’s hard for me to forget Tonya Wilson’s words. Celebration often comes after winning, but so should meditation on the sport’s sins. We shouldn’t praise one group of boys without remembering another, especially one who died playing this game, at a university that was supposed to protect him.

In the weeks after his death, I could not go far without seeing Jordan McNair. Stories about what had happened at Maryland littered internet feeds. McNair’s winning, gap-toothed grin lit up monitors. Now, searching his name delivers a bounty of memories: how the Maryland native’s high school athletic director lovingly called him “baby Shrek”; how teammates called him “Big J” and remembered him being the first to speak to everyone each morning; how he hugged his family; how his cheeks bore a bare-faced innocence before they bore a patchy beard.

Football killed that innocence on June 13, two weeks after strength coach Rick Court, head coach DJ Durkin, and the others who failed to act kept pushing McNair until his body broke. Maryland’s administration publicly discussed McNair’s death after 63 days of widespread pressure, in a report detailing a culture of sadistic tormenting. Until the days following the report’s release, school officials had never visited McNair’s parents to apologize for allowing their son to die.

It is naive to believe that McNair’s death stemmed from an aberration of protocol. That reading of what college football’s environment allows, even demands, is imprecise and misguided. Boys, frequently black boys, are killed in the grass without administrators or coaches changing the tactics that lead to caskets. The University of Maryland suspended Durkin on August 11, then reviewed the situation for months. Finally, administrators announced their intention to retain Durkin, until massive media backlash ensued, student groups planned multiple forms of protest during his first game back, and the school ultimately recanted its decision, firing the coach on October 31. But Durkin was barely away from the game before he returned. Last month, Nick Saban brought Durkin to Alabama in a consultant-style capacity in the run-up to the Crimson Tide’s national championship game appearance. (After that news was reported, Saban claimed that Durkin was there only for professional development.)

Maryland’s decision to finally fire Durkin shouldn’t be lauded as righteous or transformative. A response to pressure speaks to the presence of fear, not a desire to bring change. If football is sold to the young men who play it as their protection and their gateway to a better life, then they cannot be allowed to die, nor can meritocracy and education be positioned as rewards for flirting with death. Those in power must not be able to let a boy die and then walk away unscathed, allowed to return to the same spoils they once enjoyed. The people responsible should be expunged from the sport. Change can occur, but it will require a systemic overhaul, from ensuring that profits reach those who are currently unpaid to implementing practices that lessen, and ultimately eliminate, the risk of death to football participants. That’s a daunting task, and so as these deaths continue without real corrective measures to match, it becomes harder to believe that progress will ever materialize. The evolution of the sport is propelled on the back of the black athlete, not in tandem.

“The stronghold that sports, particularly the money, has on black communities, I don’t think it’s sunk in that you’re really playing Russian roulette with your kid’s life,” Kimberly Archie, a sports safety advocate and consultant, told me when McNair was killed. “There’s a high probability of catastrophic injury or death. It’s not this safe haven. Black kids are being used like slaves.”

Endlessly recounting the tales of what football’s culture has fostered becomes vomitous. And yet we must. The boys who died on college football’s fields deserve to be remembered. Each story reinforces what could have been averted.

In a sweaty Tallahassee gym in 2001, Devaughn Darling’s teammates heard him complaining about chest pains. Florida State coaches later said they heard nothing. Darling, an 18-year-old linebacker, struggled through the workout. The coaches insisted he continue. He smacked the floor chest first. Got up. Then crawled to a nearby wall, where he collapsed. His brother watched him die. His family buried him in a Seminoles jersey and sued the university for negligence. The parties settled, but the family didn’t see the money for 16 years because of a Florida law that prohibits universities from paying more than $200,000 in a settlement without approval by the Legislature.

After Rice University lost by 48 points in 2006, then-coach Todd Graham canceled Sunday practice. Underclassmen were required to lift and condition as a punishment instead. Dale Lloyd II, a 19-year-old defensive back, ran 16 100-yard sprints. He started breathing heavily. His legs tightened. He had trouble standing. Soon, he couldn’t lift his head. Lloyd clutched his sides in pain. Coaches ordered assisting teammates away, and then Lloyd hit the field. He lost consciousness, and never regained it, dying the next day in the hospital.

In May 2008, Ereck Plancher gasped for air as he crumpled to the field. His coach, George O’Leary, ordered all trainers and water from the area, while cursing at Plancher, a 19-year-old receiver. Central Florida teammates testified that Plancher was pushed excessively. Punished. Players watched as Plancher’s eyes rolled to the back of his head. His family was originally awarded $10 million, but the judgment was overturned on appeal after the Florida Supreme Court ruled that the UCF Athletics Association should be treated like a state agency and thus also qualify for a capped payment of $200,000, which the family received in 2017. Meanwhile, UCF built O’Leary a statue.

Football’s commitment to the normalcy of death is matched only by the mass affinity for the sport that kills these boys. Scott Anderson, the head athletic trainer at the University of Oklahoma, wrote in the Journal of Athletic Training in 2017 that football can “anticipate” death as a result of the game. “Contemporary National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football off-season performance enhancement boasts esprit de corps while, dangerously and wrongly, expecting to cheat physiological principles with predictable loss of life,” Anderson wrote. He added: “Collegiate football’s dirty little secret is that we are killing our players—not in competition, almost never in practice, and rarely because of trauma—but primarily because of nontraumatic causes in off-season sessions alleged to enhance performance.”

A February survey by the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research showed how long college football’s problem has persisted. Since 1931, more than 200 people have died playing college football, either directly, from traumatic injuries, or indirectly, from exertional or systemic ailments. In total, there have been nearly 2,000 reported deaths across all levels of the game in the same span. From 1960 to 2017, there were 150 heatstroke deaths, with 58 coming since 1996. Eleven of the deaths that have occurred since 2014 came in college football, and 90 percent happened in some form of practice.

By the group’s measure, documented in an NCAA publication, college football has resulted in the deaths of 44 boys since 2000. Forty percent of all athletic deaths in college sports due to indirect causes from 2000 to 2016 happened in college football. A 2013 study by the American Journal of Sports Medicine deemed college football players 3.6 times more likely to die from indirect causes playing their sport than their high school counterparts. The NCAA claims to be tracking player safety and death, yet there isn’t a public committee overseeing the crush of preventable deaths.

Regardless, the organization insists it’s doing well. “I do see that change is happening, and I think others are seeing the necessity for that,” Brian Hainline, the NCAA’s chief medical officer, told the NCAA publication Champion last summer while speaking about deaths in college football. “We’ve already passed the immovable place.”

In 2014, as the NCAA announced its $30 million partnership with the Department of Defense to study concussions and player health, it also bucked its responsibility and passed the onus to its member institutions. “NCAA enforcement staff is responsible for overseeing academic and amateurism issues,” the governing body said in an email to CNN. “They do not have authority to make legal or medical judgments about negligence.”

Athletic trainers in the sport consistently admit that death is a result of the culture permeating college football. Each new piece of litigation that emerges across the United States reinforces how preventable college football’s deaths are. And there are plenty of instances of abuse that warrant our attention, and corrective measures, despite not resulting in a death. Kids in Nebraska, Oregon, and Iowa are among this decade’s reminders. None of it has been enough to halt, or drastically change, the sport or its culture.

“We call it ‘lethal machismo,’” Tammi Gaw, a former athletic trainer with the Oklahoma Sooners football team, tells me. Gaw worked for the team in the ’90s under Howard Schnellenberger and saw the horrors the sport’s culture can induce, a “Junction Boys syndrome” born of the Bear Bryant football era.

The racial implications of these deaths often goes unaddressed. A 2016 entry in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences stated that racial bias occurs in the treatment of black patients and that Americans have false beliefs that black people are capable of higher levels of pain tolerance compared to white people. Such implicit bias regarding black pain creates environments where black people are assumed to be capable of withstanding anything—where racism can run a boy into the ground for the sake of a program’s heft. And because so many students playing college football are black, the inherent risk is disproportionate to their nonblack counterparts’. The black athlete is a target for ridicule, subjected to jeers and violence unimaginable to so many others not asked to prove that they are not weak.

Which means those in positions of power, the nonblack people in the crowd, the coaches who destroy black bodies, do not see black players as kin. When players fall, they do not see us in distress—for football’s gatekeepers, the moans of pain are often the goal. There should be no world, no system, that allows men like Durkin to destroy a boy’s life, continue to be paid, given back his title, and then when finally expelled from the mess he created, offered the chance of similar allowances elsewhere. Some may think that Durkin’s ultimate ouster signals progress, that dismissing the offender is the bold stance needed to trigger substantive change. But until the systemic rot that allows such tragedies to occur in the first place is addressed, that hope will remain a lie.

“There has never been a care for the black body in college football,” Derrick White, a Dartmouth professor writing a book on college football set to release in the fall through UNC Press, tells me. He added, “These athletes being looked at as labor are undervalued because they are black labor. The assumption is their bodies are disposable. The rhetoric around college football is these black boys were given something—education, money, or the right to play, a certain freedom. So if that’s the case, the assumption is you can take that away. You can force them into the meat grinder of college football without any guilt.”

The sports sociologist Harry Edwards said, in October 1999, that there would eventually be a decline in black athletic participation because of the treatment of the black athlete. The comments made the author Charles Pinckney ask in his June 2017 book, From Slaveships to Scholarships, whether there was truly a future for the black athlete in collegiate athletics: “Predominantly white institutions in general had no idea how to deal with the black student-athletes. … In other words, there was no real strategic plan in place to treat and value the black student-athlete as whole human citizens.”

If this is true—if blackness has never been accepted into the white entanglement that the collegiate-athletic complex created—then the mistreatment and, in some cases, death of the black athlete will continue. Kids like McNair will die in the hot sun. And it will continue to seem as if too few believe they should rush to save them—or that they’re even worthy of rescue.

For many, there will always be an allure in watching college football. For me, it was difficult to enjoy the showmanship this season without thinking about Jordan McNair. He will never be able to enjoy such minor pleasures as hoisting a championship trophy while confetti dots his face, as Clemson players did on Monday night. And so we have a duty not to allow his death to be reduced to being a symptom of how gruesome the game has become. None of these deaths should have occurred, and so each must be regarded as exceptional, novel, worth remembering and honoring. The people who allow these boys to die, the bystanders who do nothing despite seeing their pain, need to be remembered, too: remembered for their parts in tragedies the affected families can never forget.

I cannot forget, either. Not McNair or his ebullient beam. I cannot scrub my memory of Tonya Wilson shedding tears in front of American audiences on autumn mornings. No parent should experience this immeasurable agony, and yet black parents who send their sons to play this sport face it disproportionately. How can we love a sport where players die every year? It does not feel like anything can change. Not because change isn’t possible, but because the people keeping college football profitable for everyone except the labor would prefer to maintain the status quo rather than protest it. This doesn’t engender faith. And it doesn’t feel virtuous to opt back in. Yet many do. It is a constant struggle. Knowing all of this, how can you watch? The lack of systemic concern for the health of students laboring on collegiate gridirons is an unbearable sight that should not be met with consumership, yet our marriage to football is too strong. We will watch championship bouts, like Monday’s, with glee. It is an annual sacrament that feels eternal.

This annual struggle feels eternal, too: A sport, a culture, should not equate death or pain with strength. These boys can live. The game cannot subsist on coaches smiling at family kitchen tables, promising the allure of sparkling campuses and freedoms unknown, while, in reality, boys are being recruited to die.