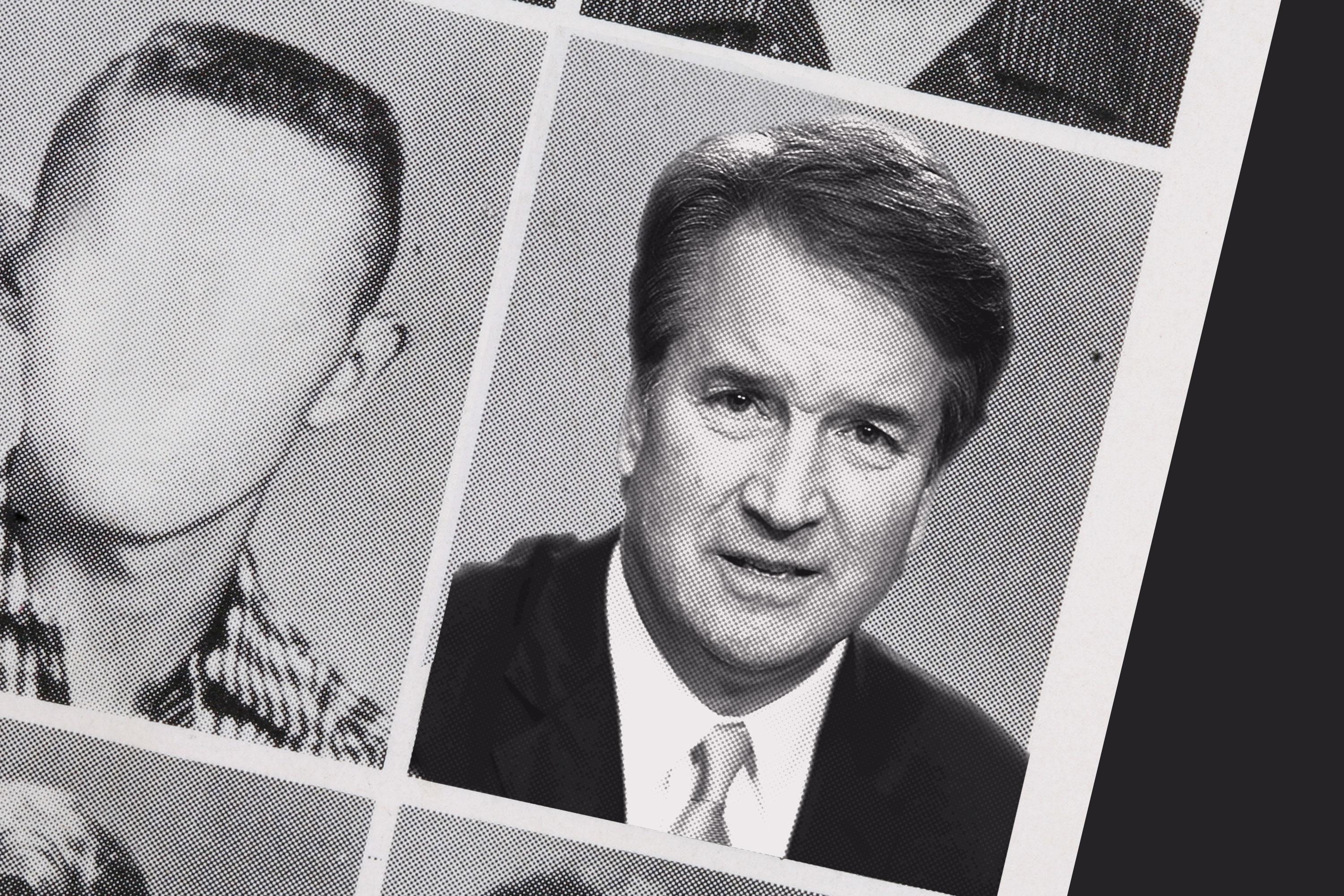

For the past week and a half, sexual assault accounts involving Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh have propelled the country into an odd, collective time warp. Suddenly, we are all teenagers again. It’s been a bit surreal: En masse, American adults have been reliving their first keggers, reflecting on the relative stupidity of their senior yearbook quotes, and, most complicatedly, bringing updated perspective to the power dynamics of their formative sexual experiences. It has been uncomfortable but necessary work.

Monday night—while Kavanaugh gave an interview to Fox News asserting the judiciously dubious logic that he couldn’t possibly be guilty of sexual assault because he was a virgin in high school and for “many years after”—The New York Times published a story digging into some of the more questionable aspects of his senior yearbook page. Along with eight of his high school football teammates at Georgetown Prep, Kavanaugh’s yearbook caption cryptically indicated that he was a “Renate Alumnius.” This turned out to be a suggestively crude reference to Renate Schroeder, an acquaintance at a nearby Catholic girls’ school. Renate Schroeder Dolphin was reached for comment about the 36-year-old reference, and, though so many of Kavanaugh’s supporters have tried to argue that things that long passed should have no bearing on the present, her anger was hot and fresh. “I can’t begin to comprehend what goes through the minds of 17-year-old boys who write such things,” Dolphin told the Times, “but the insinuation is horrible, hurtful, and simply untrue. I pray their daughters are never treated this way. I will have no further comment.”

Unless you’ve been living under a rock (and if so, I am jealous), you know the Kavanaugh story: Earlier this summer Christine Blasey Ford, a professor living in Palo Alto, California, shared with her legislators a letter stating that the Supreme Court nominee assaulted her at a party in the summer of 1982, when she was a 15-year-old student at the all-girls Holton-Arms School and Kavanaugh was a 17-year-old student at Georgetown Prep. Ford says that, while Kavanaugh was intoxicated, he and an acquaintance, Mark Judge (the author of, among other things, an elegantly titled memoir Wasted: Tales of a Gen X Drunk), pushed Ford into an upstairs bedroom, where Kavanaugh began groping her and trying to remove her clothes. When she screamed in protest, Ford says that Kavanaugh put his hand over her mouth and “they locked the door and played loud music.” She was able to escape, but as she told The Washington Post, the traumatizing incident “derailed [her] substantially for four or five years” and rendered her “very ill-equipped” to form healthy relationships with men. When Kavanaugh’s name was first rumored to be on the short list of possible replacements for retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy, Ford says she thought of fleeing the country. Since going public, she and her family have had to move out of their house. Ford is slated to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday, while the nation does its best to emotionally prepare for whatever a Twitter-era update of Anita Hill’s testimony will look like. 2018 keeps outdoing itself.

One byproduct of the #MeToo movement is that sexual assault—a topic that for so long has been couched in repression, silence, and shame—has quite suddenly become the fodder for public conversation. This has been a profound change in the national discourse, followed by some understandable whiplash. The stories about men like Kavanaugh, Harvey Weinstein, and Les Moonves are now the kind of thing that, on any given day, you might observe strangers talking about openly in coffee shops and restaurants, or on an acquaintance’s Facebook page. For millions of survivors of such incidents (according to RAINN, one out of every six American women will experience an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime), as well as members of marginalized communities that are more prone to harassment and assault, just paying attention to the news these days can leave one feeling exhausted and raw. People who lack the vocabulary, awareness, or basic facts about these issues (for example, our president) feel the need to weigh in, which can be incredibly difficult for survivors to bear. At the end of last week, a friend said that she had not known what it meant to feel triggered until the Kavanaugh news broke. (Long before the word “trigger” was distorted into connoting a political stance, you will remember that it was a bipartisan psychological phenomenon.) When President Donald Trump took office, I started joking that once we elect a female president, she will owe every woman in America a government-mandated spa week for the stress we have endured. I started saying this again last week, but I don’t think I’m joking anymore.

Plenty of Republican lawmakers have seemed disturbingly content to sweep the stories about Kavanaugh under the rug, even hoping to expedite the voting process after a second woman, Deborah Ramirez, came forward with an account of sexual misconduct, describing the circuit judge exposing his penis to her at a Yale party. “I’ll listen to the lady,” Senator Lindsey Graham said of Ford, “but we’re going to bring this to a close.” (To be so confident in the speediness of Kavanaugh’s confirmation seems incompatible with actually “listening to the lady,” but, well, nevermind.) Trump wondered, on Twitter, why then-15-year-old Ford did not immediately report her assault to the authorities, prompting one news outlet to report, not inaccurately, “The president of the United States is attacking the behavior of a traumatized teenager 36 years ago.” (This tweet ignited the firestorm #WhyIDidntReport.) “Even if true,” tweeted the Minnesota state Senator Scott Newman after Ford’s story broke, “teenagers!”

Although Kavanaugh continues to deny the women’s accounts, this controversy has forced people to think through whether a person who, say, commits a crime at age 17, or, perhaps more generally, participates in a culture of toxic masculinity, can rehabilitate himself thoroughly enough to sit on the highest court in the land. (Since it somehow bears repeating: Kavanaugh is not actually on trial; he is in the process of a rigorous employment interview for one of the most prestigious jobs in the country. Applicants to plenty of positions have been turned away for much less.) Even if true, insist those disproportionately loud supporters, teenagers! But this collective American time warp and the visceral force with which it has brought so many of us back to our pasts suggest that we are never entirely separate from the teenagers we used to be.

The factual glimpses into Kavanaugh’s teenage life suggest that he was, at best, a fratty dude who did not have the most respectful view of women and who drank heavily, or at least exaggerated how much he drank to fit in (in his class yearbook, he calls himself the treasurer of the “100 Kegs or Bust” club). Boasting about being a “Renate Alumnius” in his yearbook, of course, does not prove Ford’s or Ramirez’s accounts—but it does suggest that he was kind of an immature jerk who viewed women as conquests, just like the guys he associated with. What I would want from a prospective Supreme Court justice is the moral acumen to at least admit that, if only to discuss in honest terms how he’s matured. “This is hardly disqualifying for Kavanaugh, even in the context of other allegations,” New York Times writer Robert Draper tweeted of the yearbook. “But one would like to think that such awful adolescent male behavior would merit an apology & assurance that he’d grown from this (which is not a given).” Kavanaugh’s po-faced denials strike a stark contrast with Texas Democratic Senate hopeful Beto O’Rourke, who has thwarted his opponents’ attempts to dredge up his past misdeeds (which include a DWI and a burglary charge) by owning up to them and talking about them with candor and adult perspective. Kavanaugh seems unwilling to do the same.

The events of the past few weeks have reminded us that selective separation from the unfortunate parts of one’s past is a privilege afforded to only certain people. Women are rarely among them. Perhaps this explains why, since the Kavanaugh news first broke, almost every woman I know has been experiencing what it does not feel an exaggeration to call communal psychic pain, reliving both their own past traumas of sexual harassment and violence alongside all of the instances that others have privately confided in them about over the years.

Over the weekend, loved ones told me harrowing stories I hadn’t heard before, some of which took place decades ago but were recounted in vivid detail. I told close friends things I’d not previously shared with them, and felt a little lighter for it. While many GOP lawmakers have been in panicked denial, scanning such trivial evidence as Kavanaugh’s calendar from the summer of 1982, many female constituents have been doing much more difficult and vital work: We’ve been experiencing no less than a mass public-consciousness-raising.

Any elected official would be wise to pay attention to this rising wave. To ignore it, diminish it, or deny that it is happening is to be out of touch with the rapidly changing mood of the American electorate.

Last Thursday, 17-year-old Parkland survivor and gun control activist Sarah Chadwick retweeted a story published that day in the Yale Daily News, detailing the “hijinks” common to the fraternity to which Kavanaugh once belonged. (That same fraternity was temporarily banned from Yale in 2011 for chanting, outside the university’s Women’s Center, “no means yes, yes means anal.”) That same week, her 18-year-old classmate Emma Gonzalez wrote a tweet encouraging campus Greek life to prioritize voter registration in time for the midterms (“How many sororities and fraternities can get Voter Registration set up for September 25th? Let’s get this November 6th PACKED,” she wrote in a tweet that has been favorited 39,000 times.) Monday, during the national walkout to support sexual violence survivors and protest Kavanaugh’s nomination, Parkland activist David Hogg retweeted a picture of several teenage boys with the caption, “We walked out today because NOT all high school boys are rapists like #Kavanaugh and because, unlike the top senate, we #BelieveSurvivors.”) The younger generation is rebelling against its elders. Thank God.

And so while the elders of our government have been defending a rich white boy’s good ol’ American right to experiment with sexual assault, the teens have been assuming the vacant role of the adults in the room. It is particularly surreal that this high-profile inquiry into Kavanaugh’s youth is happening the same year as the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and the subsequent teen-organized March for Our Lives. Kavanaugh may have been able to live out a prolonged adolescence well into his time at Yale, but we see more and more examples of kids growing up faster and taking responsibility for their actions at a more precocious age, perhaps because our lawmakers continue to pass the sort of lax gun legislation that makes them fear that they will be shot at school.

But, suffice to say, the kids are watching. The New York Times asked some high school students what they thought of the Kavanaugh news, and they were predictably wise. Said one 17-year-old girl, “The language being used by a lot of Republicans is eerily similar to the way boys sound in high school.”

The Supreme Court is a lifetime appointment; Judge Anthony Kennedy, who Kavanaugh hopes to replace, served for 30 years. If Kavanaugh’s tenure is roughly as long, that means that these will be the adults he’s governing: When today’s 17-year-olds are in their mid-40s, he will still be making decisions about how they live their lives, who they are allowed to love, and the control they have over their bodies. We owe it to them to get this one right. The world is changing, and in the coming decades the population that Kavanaugh would be serving will not look and think like it has in the past. We should welcome this shift. We should listen to the massive outpouring of trauma that these accounts have let loose. We should teach our sons that just because boys have been boys in the past doesn’t have to mean they will be in the future. Unless, of course, they insist on being the old-fashioned kind that refuse to grow up.