How ‘Fortnite’ Conquered Gaming and Mainstream Cultures Like Few Before It

With an assist from some celebrity players, the online third-person shooter became part of the monoculture in 2018. How does it stack up compared to previous games that reached cultural ubiquity?In 1992, Tim Sweeney knew he needed a new name for the fledgling game-development company he’d founded the year prior, Potomac Computer Systems. He was entering a market controlled by bigger companies, and he wanted his one-person studio to sound like it belonged. He decided on something almost comically grandiose: Epic MegaGames. It was, he said decades later, “kind of a scam to make it look like we were a big company,” instead of a single college kid working out of his parents’ house.

Sweeney’s scam should earn his face a place on the “Fake it till you make it” Mount Rushmore. Thanks to Unreal, Gears of War, and lucrative licensing of (and royalties from) its Unreal Engine, his company prospered, and its headcount swelled to 700. Along the way, it dropped the “MegaGames” from its name; once it actually was one of the giants, it no longer needed a startle display. In retrospect, though, the original name was more of a prophecy than a scam. A quarter-century after that rechristening, Epic released the most mega game of them all: Fortnite, the online third-person shooter that dominated both gaming culture and mainstream culture in 2018 to such an extent that maybe more than any game that came before it, it dissolved the distinction between the two.

Fortnite was years in the making and months in the taking of the cultural crown. Epic announced the game in late 2011 shortly before the company pivoted to a “games as a service” model, driven by the realization that each new installment in the Gears of War series — which made most of its money via the one-time, up-front sticker price players paid to get the game — was costing more to make and turning a smaller profit. Rather than stay on the sequel assembly line, Epic intended to traffic in “ongoing games” that would evolve post-release and make money via microtransactions, in-game purchases of downloadable, cosmetic content.

To that end, it accepted an outside investment — $330 million for a roughly 40 percent share of the company — from Chinese conglomerate Tencent, which already owned a majority stake in Riot Games, a developer that had made that model work with League of Legends. In the wake of the Tencent transaction, Epic’s shift in philosophy prompted several prominent employees to depart. The company completed its rebirth in 2014 by selling the Gears series to Microsoft and announcing that Fortnite would be free to play.

Set back by that exodus of developers, the demands of Epic’s other projects, and routine technological hurdles, Fortnite gestated slowly. Epic began building the game in Unreal Engine 3 but soon realized that the old software wouldn’t have enough horsepower and designed Unreal Engine 4 partly to fulfill its ambitions for Fortnite. The game went from a PC exclusive to a multiplatform title, and Epic spent years fine-tuning its formula for fun based on knowledge gained from limited public prerelease playtesting beginning in late 2014.

A $40 Early Access version of Fortnite finally arrived on Windows, Mac, Xbox, and PlayStation in late July 2017. At the time, there was one way to play: “Save the World,” a cooperative, objective-based survival mode in which four players team up in a postapocalyptic landscape to fight quasi zombies, save survivors, collect resources, build shelters, and repel a devastating storm. By then, though, the success of PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds had popularized a new multiplayer mode: the battle royale, in which many players compete to be the last person standing on an ever-shrinking map. Epic realized it could capitalize on the latest trend by building a battle royale mode for Fortnite, which it completed in just two months. (Early this year, PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds publisher PUBG sued Epic for copyright infringement but subsequently dropped the suit.)

It’s a big enough phenomenon that it’s made it onto sitcoms and talk shows and people are saying, ‘Well, I could either go out with my friends tonight or stay home and play Fortnite.’Steven L. Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games

Rather than bundle “Battle Royale” with the preexisting “Save the World,” Epic made its new mode a standalone game that was accessible for free. Whereas “Save the World” was a modest success, attracting roughly 1 million players in its first month, “Battle Royale” was a smash, drawing 1 million on the day it debuted and 10 million within its first two weeks. Epic soon assigned most of its staff to further Fortnite’s development and shuttered the competing Paragon, a free-to-play game that came out before Fortnite. The game has since been ported to iOS, Switch, and Android, and the stubbornly isolationist Sony capitulated to public pressure and enabled cross-platform play for Fortnite and other games, allowing people on any platform to play against one another. At The Game Awards this month, Fortnite was nominated for Best Mobile Game and Best Esports Game and named Best Multiplayer Game and Best Ongoing Game.

Even without launching in China, where it and other big games have reportedly recently been banned, Fortnite has grown rapidly, increasing its count of registered users by 60 percent between June and November to a total of 200 million. Epic announced that more than 78 million people played the game in August and, in November, reported a peak of 8.3 million concurrent players, more than double its previously announced peak from February and easily surpassing the peak number of people playing every game on Steam combined. In-game purchases have generated billions of dollars in revenue at an estimated rate of hundreds of millions per month, a record for a free-to-play game. Small wonder, then, that Epic funded a $100 million prize pool for competitive play, dwarfing any other esport, and even smaller that the company raised $1.25 billion in October, the largest non-IPO, gaming-related investment ever. At that time, the company was valued at about $15 billion, up from $4.5 billion in May and $660 million in 2012. Tencent got a good deal.

In terms of sheer number of players, Fortnite is one of the biggest games ever, but probably not the biggest; in 2016, League of Legends boasted 100 million monthly active users, and Pokémon Go was downloaded 130 million times in its first month on the market. Where Fortnite truly separates itself is in cultural prominence and staying power. There, the game may be the biggest, baddest occupant of the Battle Bus.

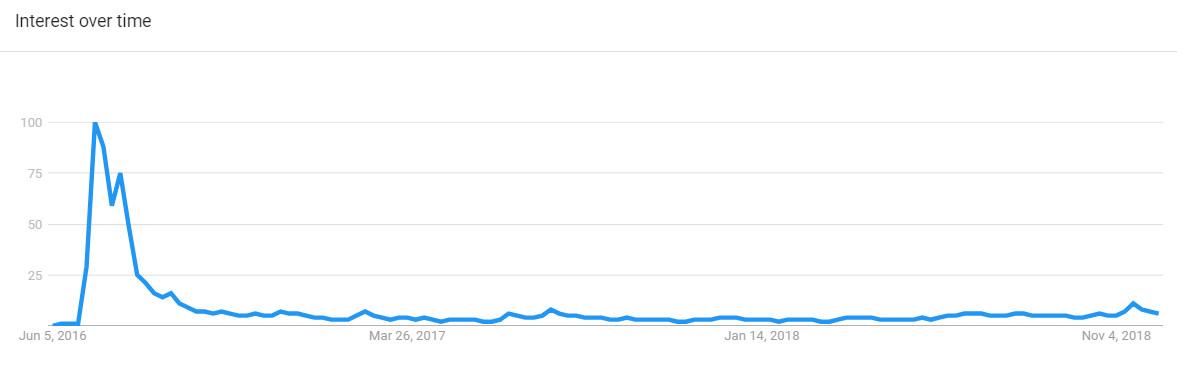

A comparison to Pokémon Go may be helpful here. Although there are still plenty of people playing the game (albeit far fewer than before), its heyday as a cultural phenomenon lasted only a few months, as indicated by worldwide Google Trends search data.

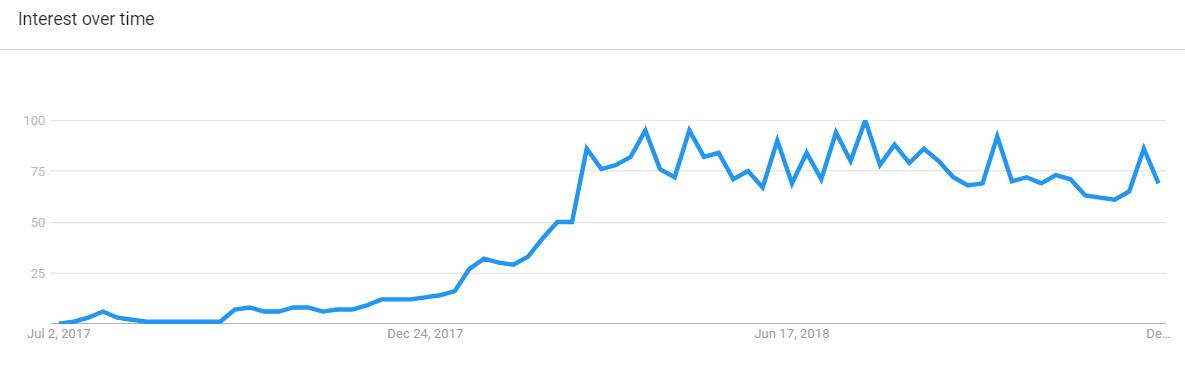

Fortnite, meanwhile, has more or less stayed at the heights it attained in March.

Fortnite’s continued presence in the spotlight is partly attributable to Epic’s efforts to keep plying players with content; the company has found ways to tell a story in a game that ostensibly lacks one, and it’s continued to add content and tinker with the gameplay. Epic “knows their fan base better than just about any developer out there,” says Dustin Hansen, author of the video-game history book Game On! “They engage with the fans with contests to pick new emotes, they promote popular streams, and their quick response time allows them to jump on trends and topics while the joke is still hot.” The game is also sticky to its core, roping in players with a savvy incentives structure based on nabbing loot; snagging limited-time, status-displaying items; and rewarding skill while still mixing in enough randomness to give lesser players hope.

More than that, though, Fortnite is also a crossover success whose organic promotion by prominent figures makes the hoi polloi want to play. Google searches for the game spiked in March, and while that was likely related to its arrival on iOS, it also stemmed from a massive celebrity boost. In the early East Coast hours of the Ides of March, high-profile Fortnite streamer Ninja hosted a stream that featured rappers Drake and Travis Scott, Pittsburgh Steelers wide receiver JuJu Smith-Schuster, and Megaupload founder Kim Dotcom. That confluence of figures from the gaming, internet, music, and sports worlds set a record for most concurrent viewers on a single Twitch stream and also established who Fortnite was for: everyone. Jocks and nerds; artists and tech entrepreneurs; 20-somethings and 40-somethings; black people and white people; Americans and non-Americans. All were welcome.

Although Fortnite is a preoccupation among kids, it’s not the kind that excludes olds; in some cases (including Ringer boss Bill Simmons and his son), it can be a multigenerational bonding experience. And the mainstream-culture crossovers have kept coming. Fortnite is big with basketball players, baseball players, hockey players, and football players, not to mention the NFL, which partnered with Epic to sell custom skins. Athletes aren’t just playing — and getting caught on stream complaining about their bosses — when they’re out of uniform; they’re bringing Fortnite to the field via celebrations in various soccer leagues and World Cup competition; end zone dances; Astros and Red Sox celebrations and All-Star Game promo videos; and basketball shoes. They’re streaming it and tweeting about it, as are actors and musicians from Finn Wolfhard to Joe Jonas to Chance the Rapper. When YouTube produced a year-in-review video to present to its advertisers, it went with a Fortnite theme. Thanos briefly became a playable character, and Wreck-It Ralph made a cameo.

Weaving together these disparate strands makes Fortnite feel like the nexus of culture. It’s unclear whether Roseanne Barr and Norm MacDonald actually play or just joked that they did because everyone else was, but that’s the point; the game is ubiquitous enough that we’re all aware of its popularity, whether we play it or not. “It’s a big enough phenomenon that it’s made it onto sitcoms and talk shows and people are saying, ‘Well, I could either go out with my friends tonight or stay home and play Fortnite,’” says Steven L. Kent, author of The Ultimate History of Video Games.

As with any cultural craze, there has been a backlash. In one bit of fallout from the game’s bid to participate in the milieu of the moment, actors, rappers, and Instagram stars alike have filed suit against Epic (or at least complained), alleging that the company stole their signature dances for use as Fortnite emotes, which have been ambassadors for the game. “These dance moves spread, meme-like, into school playgrounds, along with their memorable names, such as ‘Floss’ and ‘Hype,’ and acted as a kind of guerrilla marketing,” says Simon Parkin, author of Death by Video Game and An Illustrated History of 151 Video Games. “Children would learn the dances, then want to play the game from which they ‘originated.’”

That desire, in turn, brought Fortnite to the attention of inquisitive caretakers who wondered whether the game (which the ESRB rates as suitable for teens) was safe for kids’ consumption. No new form of electronic entertainment can ascend to the top of the cultural totem pole without prompting paternalistic alarmists to stoke largely unsubstantiated fears about addiction, bad attitudes, and even violence — the last of which feels particularly flimsy in Fortnite’s case, given its brightly colored, cartoonish visuals, lack of blood, and mostly playful, nonviolent weekly challenges that turn the game into more of a social space than a “murder simulator.”

“In a world where we’ve now had Kingpin and Manhunt and a million other different games that frankly have been on the horrific side … [Fortnite] is nothing,” Kent says. “There’s been a race to try and see who could be the most violent the last 20-some-odd years. … And Fortnite really is not trying to do that. Fortnite is really, truly just trying to entertain.” Because it’s less likely to offend delicate sensibilities, Fortnite won’t create the controversy of Mortal Kombat or Grand Theft Auto’s “Hot Coffee” mod, which led to lawmakers’ involvement. That prevents it from shaping the cultural conversation in the way that those games did, but it also removes a reason for protective parents to keep it from their kids. Instead, some parents are paying for Fortnite tutors.

Epic’s Knickers-sized cash cow is the latest in a long line of games that developed a sizable cultural footprint, from the precedent-setting Pong to arcade classics like Space Invaders and Pac-Man, to the late-’80s sensations of Tetris and Super Mario Bros., to the ’90s splashes of Sonic the Hedgehog, Doom, and Pokémon, to 2000s juggernauts GTA, Call of Duty, Halo, and World of WarCraft, to more recent landmarks like Minecraft and casual, mobile milestones like Angry Birds, Candy Crush, and Pokémon Go. In the years since most of those games debuted, though, the world has evolved in ways that made it more feasible for Fortnite to seep into every orifice of American culture in 2018.

There’s been a race to try and see who could be the most violent the last 20-some-odd years. … And Fortnite really is not trying to do that. Fortnite is really, truly just trying to entertain.Steven L. Kent

“Arguably, those who love games are more vocal online and on social media — and appreciate those media more — because games aren’t reviewed in old media generally,” says Harold Goldberg, author of All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture. Thus, the migration of culture to spaces like Twitch and YouTube, where games — specifically Fortnite — reign supreme, has permitted a greater degree of mainstream permeation. Fortnite is especially well suited to take advantage of the rise of streaming and the ascendance of esports. “Fortnite is one of those rare games that is just as much fun to watch as it is to play,” Parkin says. “Each game lasts around 20 minutes, has a clear start, middle, and end, and compellingly ratchets up the tension as it progresses.”

The closest comp for Fortnite’s creeping omnipresence may be the golden age of arcades in the late 1970s and early 1980s. “For most existing generations, when you said ‘arcades,’ they were thinking about something you went to at Coney Island,” Kent says. “And then the next thing you know, Americans are dropping 20 billion quarters in a single year [1981]. They spent 75,000 hours playing arcade games.” In 1982, Space Invaders and Pac-Man made the cover of Mad Magazine, and Pac-Man inspired a cover of Time. Martin Amis wrote a book about arcade games — with a foreword by an openly arcade-loving Steven Spielberg — and arcades became a common social space and cinematic setting.

Even so, the arcade craze was the product of more than one game, and arcade enthusiasts still had to leave the house and spend money to play, two big barriers that time and technology have torn down. As Hansen says, “[Fortnite] is free, plays on just about every device you can get your hands on, and from the get-go it’s super easy to play,” while also allowing for deeper mastery over time. It’s difficult for a game from any previous era to compete with the most prominent title from a period when every other pocket contains a full-fledged gaming machine.

Fortnite is a much more complex “gamer’s game” than some of the previous mobile blockbusters, but that hasn’t held it back. Mark Wolf, a communications professor at Concordia University, observes that Fortnite combines “the social online competitive gameplay of MMORPGs with the noncommittal nature of casual games, resulting in something which is social and competitive but has game sessions which are over quickly and can be picked up quickly and played by anyone.” Epic’s genre-melding alchemy makes Fortnite a fit for quick bursts as well as for more marathon sessions.

Parkin opines that it’s “possible to argue that Fortnite is the most impactful cultural phenomenon in games so far,” noting that “Minecraft has undoubtedly been the holder of that accolade up to now. That game is so deeply rooted in the public imagination, and so tenacious in its appeal to young people, parents and even teachers.” Epic is attempting to siphon some of Minecraft’s appeal by doubling down on Fortnite’s construction mechanics in a newly announced third mode, “Fortnite Creative.” That’s one component of Epic’s campaign to retain its massive audience’s interest and expand its online empire. The company also launched its own digital vendor, the Epic Games Store, in an effort to undercut Steam, and a Fortnite World Cup is coming in 2019.

Hansen says, “We might be looking back in a decade at Fortnite and saying it really is the game that knocked Minecraft off the block as the most beloved, all-players-welcome game ever created.” Or, well, we might not. “What’s tricky with Fortnite is that it’s still early days,” says Tristan Donovan, author of Replay: The History of Video Games. “Is it a fad or not? Will it still endure in five years’ time, or will it be the Tamagotchi, Guitar Hero, or Skylanders of 2018?”

It’s almost impossible to predict Fortnite’s future with any accuracy, just as it was tough to foresee last September that Fortnite would so quickly eclipse PUBG. Fortnite has already inspired its own copycats. Maybe one will someday supplant it, or perhaps players will tire of battle royales.

When Fortnite fades one day, we won’t remember it the way we do series associated with one star. “There was a poll taken in the 1990s saying that Mario was more recognizable [among American kids] than Mickey Mouse,” Goldberg says. “I think Fortnite needs to have a lasting character, one that everyone knows, for it to be considered for a place in the pantheon of legendary gaming phenomena.” It’s true that Fortnite lacks a face that could carry a movie, but maybe its missing mascot is another reflection of the many ways in which gaming has grown up. Fortnite is a vessel, a place where we play. Its players, and the rest of the culture, supply all of the character it could need.