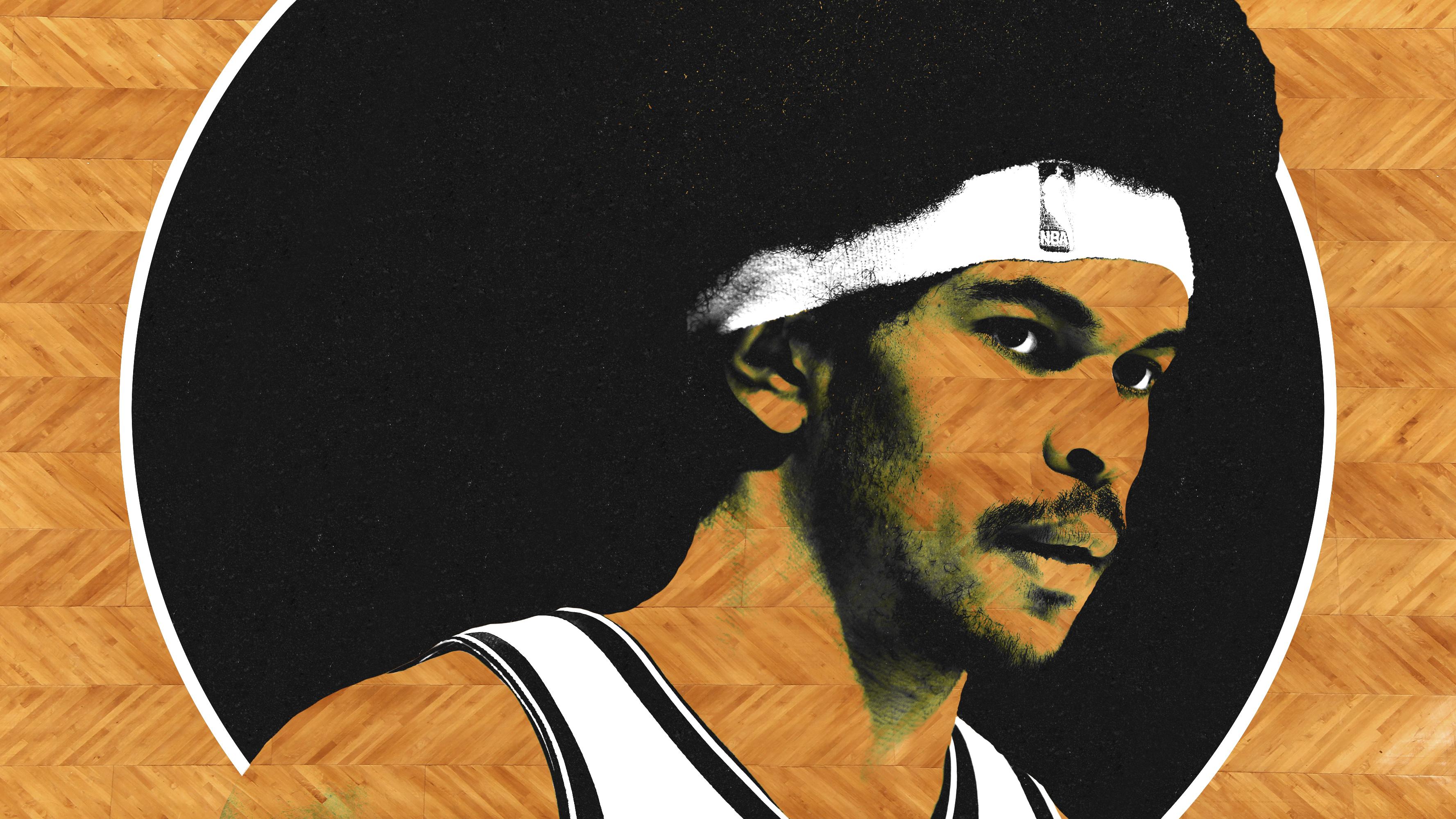

The Center Cannot Hold (the Weight of a Modern Franchise Alone)

The struggling Brooklyn Nets are searching for a true focal point after Caris LeVert’s serious injury, and Jarrett Allen’s steady ascent makes him a viable candidate. It hasn’t happened, and that’s by design.Jarrett Allen is ahead of schedule. Most centers taken outside the lottery are late bloomers who need years to establish themselves in the NBA. Clint Capela and Rudy Gobert each averaged fewer than 3.0 points per game as rookies. Allen, the no. 22 overall pick in the 2017 draft, hit the ground running in Brooklyn. He became the starting center halfway through his rookie season, and he’s been one of the best young big men in the league in Year 2. What the Nets need to figure out is how valuable a player like that even is in 2018.

Allen, who is averaging 12.2 points on 59.8 percent shooting, 8.3 rebounds, and 1.6 blocks in 28 minutes per game this season, is playing like a top-10 pick. There’s not much difference between him and the five big men taken in this year’s top 10 when you translate their stats over 36 minutes of playing time. He leads in some categories and trails in others, but he’s not an outlier either way:

Allen vs. Rookie Bigs

While Allen has a year of NBA experience on the rookies, the more important metric when comparing player development is age. Marvin Bagley III, Jaren Jackson Jr., and Wendell Carter Jr., who were all born in 1999, are significantly younger than Allen, Deandre Ayton, and Mohamed Bamba, who were born in 1998. Allen will turn 21 in April, which makes him one month older than Bamba and three months older than Ayton. He was pushed ahead in school instead of being held back, allowing him to get a head start on his NBA career.

Allen was a McDonald’s All American who was highly regarded in his own right coming out of high school. He just didn’t fit the typical mold of an elite recruit. He avoided the AAU scene almost entirely, and has a wide variety of interests outside of basketball, which led to predictable whispers about his love for the game in the pre-draft process. The off-court concerns might not have mattered had he dominated in his only season of college, but he had an up-and-down year on an underachieving Texas team that won only 11 games. It’s a moot point now that he is settled in Brooklyn, where he is widely praised for his intelligence and work ethic.

“He’s well-adjusted,” said Spencer Dinwiddie after a 119-113 loss to Dallas on November 21. “He’s super talented. He uses both hands effectively. He’s grown as a rim protector big-time, and he’s a phenomenal finisher. He makes it easy on me.”

At 6-foot-11 and 237 pounds with a 7-foot-5 wingspan, Allen looks the part of a rim-running center. He has the size and athleticism to catch lobs on one end of the floor and anchor the defense on the other. Part of his issue in college was the way he was used. Texas head coach Shaka Smart tried to turn Allen into an old-school bruiser, with 27.8 percent of his offensive possessions coming out of the post. He’s posted up 35 times total (which led to 10 shot attempts) in two seasons in Brooklyn.

“Back-to-the-basket moves are what all big men grew up doing. It’s something I trained for almost all my life, and now I’m having to learn a different style,” Allen told me in a phone interview last week. “Of course, now kids my height are dribbling the ball up the court, bringing it up, and crossing people over.”

Allen grew up at the very end of a generational shift in the game. There aren’t many high school big men trying to play in the post anymore. The irony is that he was training for something he wasn’t well suited for, and his success in the NBA is a perfect example of why the shift happened in the first place. Allen doesn’t have the bulk to wrestle for position down low. He’s a fluid athlete who is more suited to playing in space like he does with the Nets. Brooklyn doesn’t run many plays for its young big man, but he is involved in almost every play it runs. The spread pick-and-roll is the foundation of its offense, with Allen setting screens at the top of the key and then rolling hard to the rim, sucking in the defense, and creating openings for its ball handlers and spot-up shooters.

“Other teams definitely know I can be a threat when rolling,” Allen said. “So some teams have a guy tag me, or they are playing a more conservative style of defense, knowing where I’m at all the time. Just keeping a body on me.”

Allen, who is in the 71st percentile of roll men leaguewide and the 78th percentile when finishing around the rim, has already made a name for himself as a dunker. There aren’t many guys his size with his ability to elevate quickly:

Allen isn’t just a one-dimensional dunker. He has the hands to grab balls in traffic, the basketball IQ to time his cuts perfectly, the touch to finish from a variety of release points, and the vision to make the extra pass if the defense sends help. His assist-to-turnover ratio has gone from negative in Year 1 (0.64:1) to positive in Year 2 (1.23:1). He’s also one of the few rim runners who can knock down free throws (career 74.1 percent on 2.5 attempts per game) when he’s sent to the line.

“I think the sky’s the limit for him. He’s one of those young players where every game you see something new,” said Nets head coach Kenny Atkinson before their game in Dallas last month.

Allen has taken an even bigger step forward on defense this season. He’s increased his total rebounding percentage by 1.6 points and has become one of the best rim protectors in the league. There are 14 players who have defended at least seven field goal attempts per game within 6 feet of the rim this season. Allen is fifth among them in defensive field goal percentage allowed (54.0 percent) on those shots, ahead of guys like Gobert, Capela, and Anthony Davis.

It’s all part of the natural progression of a young big man. Allen is bigger and stronger than he was last season, and he has a better understanding of what his coaches want from him.

“You don’t really know what to expect as a rookie. You don’t know who you are playing against and how they like to play,” said Allen. “You have to know what certain guards want to do when defending the pick-and-roll: do they like to shoot a certain way, or pass that way, and their tendencies [will tell you] about how to block their shots.”

Allen has excelled in everything the Nets have asked him to do. The problem is they don’t ask him to do all that much. He rarely creates his own shot on offense, and he doesn’t venture outside the paint on defense. Brooklyn is one of the most analytically inclined organizations in the league, and its system puts its centers into a narrowly defined role. The Nets generate a higher percentage of their offense (7.6) from the roll man in pick-and-roll situations than all but three teams, and they are dead last (1.2 percent) in post-ups.

The Nets are the ultimate system team, but their system has collapsed without Caris LeVert, who went down with a dislocated ankle November 21. LeVert was in the midst of a breakout season, averaging 18.4 points on 47.5 percent shooting, 4.3 rebounds, and 3.7 assists per game. Brooklyn was 6-7 before his injury, but has lost nine of the 11 games since and effectively fell out of the Eastern Conference playoff picture. Allen is now their best two-way player, but he can do only so much to impact the game in his current role.

Allen still spends most of his time on offense setting screens. He’s just doing it for Dinwiddie, D’Angelo Russell, and Shabazz Napier instead of LeVert, and they are trying to make up with volume what the team lost in efficiency. He’s a release valve whose production is dictated by the decisions of the defense. He has the second-lowest usage rate (16.5) of any player in their rotation, ahead of only backup center Ed Davis, and the highest true shooting percentage (63.8). His points come mostly off his own activity level: rolling to the rim, cutting off the ball, crashing the offensive glass, and getting out in transition.

“I always tell [Allen] to stay aggressive. I don’t like when he gets the offensive rebound and he kicks it out. As a big in that situation, you have to be a little selfish, especially how our offense is set up,” Davis, a nine-year NBA veteran who has become a mentor to Allen in his first season in Brooklyn, told me in the locker room before their game in Dallas. “The bigs don’t get a lot of touches. When he gets the ball in the paint, I tell him, fuck kicking it out. Throw it back up. You might take a couple bad shots, but what is coach going to do? He ain’t going to take you out.”

That same efficiency-minded approach extends to the Nets defense. They have Allen drop back on the pick-and-roll to protect the rim and ask their guards to chase ball handlers over screens and prevent them from getting open 3s. The idea is to dare opposing teams to take as many long 2s as possible since the numbers should work in their favor over the course of a game. They are no. 2 in the league in opponent field goal attempts (11.3) from 16-24 feet out and dead last in the number of shots they allow from outside of 24-plus feet (25.0).

There are limitations to that approach, which you can see in Allen’s defensive metrics. He’s in the 17th percentile of players when defending ball handlers in the pick-and-roll. The Nets guards don’t get over screens well, and Allen is dropping so far back that he can’t contest the open shots that opposing guards are walking into. They give him fairly rigid rules to follow rather than trusting his instincts. He has been the primary defender in 248 pick-and-rolls that have ended in either a shot or a turnover this season, and the overwhelming majority of those plays have come from the ball handler (237) instead of the roll man (11). There’s nothing Allen can do to help his teammates on plays like this:

One possible solution would be for Allen to extend out on the perimeter and pick up the ball handler himself. While the Nets switch screens only in emergencies, Allen has held up when he’s been caught on an island this season. He’s in the 85th percentile of players when defending isolations in 36 possessions.

“I feel comfortable doing it. I know I’m athletic enough to guard a guard out there. I’m not calling myself the Defensive Player of the Year or anything, but I can hold my own,” said Allen.

Atkinson and GM Sean Marks have to make a decision with Allen. Getting more out of him would mean making changes to their system, which won’t be easy to do halfway through the season. They may not want to, either.

Featuring Allen would change the structure of the Nets offense. He’s not a good enough shooter at this stage in his career to force defenders to guard him outside the paint, which prevents him from using his quickness to face them up and go around them. The only way for him to create his own shot is to back people down in the post, which is one of the most difficult ways to score in the NBA. Joel Embiid is having an MVP-caliber season while generating 1.054 points per possession in the post. That number would put him in the 74th percentile of post scorers around the league and the 41st percentile of roll men.

Brooklyn would rather Allen work on his 3-point shot than his post game. Atkinson has given his center the green light to shoot from behind the arc even though there’s little evidence that he can be effective from that range. He was 0-for-7 from 3 in college and is 8-for-32 (25.0 percent) in his two seasons in the NBA.

“He’s shown he can shoot the corner 3, not as much this year, but I think he’s very capable. At 7 feet with his athleticism, he’s a modern-day center and I think he can even expand that position because I think he can play on the perimeter, too,” Atkinson said. “We run him to the corner sometimes. We believe in space and sometimes we’re running spread pick-and-roll and we don’t want him in the dunker role. Having that space, especially at the end of the game, is valuable.”

The NBA has become a league defined by space, with offenses trying to create it and defenses trying to take it away. Most NBA coaches keep at least four 3-point shooters in the game to force the defense to cover the entire floor, which means there’s an opportunity cost to playing a non-shooter like Allen. Playing him big minutes makes it almost impossible to have another non-shooter in the rotation.

The Nets are a perfect example of how this lineup dynamic plays out. Their most commonly used five-man unit this season featured two guards who could play on or off the ball (Russell and LeVert), one roll man (Allen), and two one-dimensional shooters at the wings (Jared Dudley and Joe Harris). Brooklyn hasn’t found a group that clicks without LeVert. His absence has exposed the limitations of Dudley and Harris, but taking the best shooters out eliminates the spacing that Allen needs to be effective. While they need to lean on their defense without LeVert, their best perimeter defender (Rondae Hollis-Jefferson) is a poor outside shooter who doesn’t mesh with Allen.

Building a defense around Allen is tricky, too. His agility for a big man is intriguing, and he might be unleashed in a switch-happy scheme like the one Rockets use with Capela. The problem is that his quickness comes at a cost inside. There are still a few big men in the NBA who can bully smaller players, and Allen has to deal with them, too. He doesn’t have the bulk of a guy like Embiid, who is listed conservatively at 7 feet and 250 pounds. The 76ers star dominated Allen in a 127-125 victory on November 25, and scored 32 points on 11-of-19 shooting.

“It’s not even that I want to get bigger. I have to to really succeed in this league when playing against bigger guys,” said Allen. “I have to bulk up.”

Allen will get stronger as he moves into his 20s, but he has to be careful about changing his body too much. Like a lot of young big men who come into the league these days, he has to maintain a difficult balance between adding strength without losing speed. There are more defensive demands on the center position than ever before because they have to guard so many different types of players.

“If you can’t shoot the 3 on a consistent basis, or have a seriously elite handle as a big man, you are definitely a 5 in this NBA,” Davis said with a smile. “I wish I could be a 4.”

The list of players Allen has guarded this season features guys of all shapes, sizes, and skill sets. Some of his most frequent opponents are old-school behemoths like Hassan Whiteside, Marc Gasol, and Andre Drummond. Yet he’s also had matchups with small-ball 5s like Jeff Green and stretch 5s like Mike Muscala, as well as guards like Steph Curry, Chris Paul, and John Wall. It’s almost too much to ask of any one player.

The best teams in the NBA aren’t built around one dominant center. The Warriors won the past two titles with Draymond Green and Kevin Durant moonlighting at the 5 in the playoffs and a platoon of bigger bodies absorbing the physical pounding that comes with the position in the regular season. The top two teams in the East this season have waves of players they can rotate through at center: Brook Lopez, Ersan Ilyasova, and Thon Maker for the Bucks; Serge Ibaka, Jonas Valanciunas, and Pascal Siakam for the Raptors. Both teams could even go smaller with four wings around Giannis Antetokounmpo or Kawhi Leonard, respectively, in a theoretical Finals matchup with Golden State.

There might be a ceiling on Allen’s game even if he becomes as dominant defensively as Gobert or Capela. Gobert was the Defensive Player of the Year last season and he struggled to defend Paul and James Harden at the 3-point line in the second round of the playoffs. Capela is more mobile than Gobert, but his offensive limitations were exposed in the Western Conference finals against the Warriors. Houston was more effective in that series with P.J. Tucker at the 5.

Gobert and Capela haven’t raised the games of their teammates this season. Utah hasn’t made enough 3s to create room for Gobert to roll to the rim, and the Jazz have slipped to the bottom of the West. Capela is more a creation of Harden and Paul than the reverse. There’s not much he can do to slow down the aging process for CP3. Houston doesn’t change its offense to get him the ball more when Paul struggles anymore than Brooklyn has featured Allen without LeVert.

A center in the NBA has become like a running back in the NFL. Teams don’t have to build their offenses around those positions because their production is a function of a modern offense. A good quarterback, set of wide receivers, and offensive line will stress a defense so much that any decent running back can put up big numbers. The Steelers replaced Le’Veon Bell with James Conner and haven’t missed a beat. Similarly, an NBA team that can put three 3-point shooters around a quality point guard will create enough space in the half court that any decent center can put up huge numbers when rolling to the rim.

Allen may not be as gifted as Ayton, but the Nets are using him in a system that allows him to rack up similar per-36-minute averages to the no. 1 overall pick. While it would be nice to get more production from their center, that isn’t the position that is holding them back. They began the season with a starting lineup of LeVert, Russell, Allen, and two placeholders at the wings in Dudley and Harris. Imagine if they could insert into their lineup a player like Jayson Tatum, one of the first-round picks they sent to the Celtics as part of their disastrous 2013 trade to land Kevin Garnett and Paul Pierce.

There’s no way to replace wings with 3-point shooting ability and the size to defend multiple positions. The only way to get those players is at the top of the draft. This is the first season in which the Nets have had their own lottery pick since Atkinson and Marks took over in 2016. They knew it would be a long haul, so they installed a system that would create the most efficient shots possible, regardless of personnel. Changing it to build around a center would defeat the whole point. Allen, for as good as he has been the past two seasons, is not a cornerstone—at least not on a franchise that views the production at the center position as a replaceable commodity. His job is not to lift Brooklyn out of the lottery, it’s to complement the players who can.