Age is an extremely important factor in predicting future performance for all players, from prospects to veterans. Minor leaguers who beat up on older competition tend to become better major leaguers than older prospects who put up similar stats, while a 26-year-old free agent can command more money and a longer contract on the open market than a 32-year-old free agent, because the team will be paying for less of his decline phase.

This combination of youth and performance is a good reason to be extremely positive on Nationals outfielder Juan Soto, who hit .292/.406/.517 as a 19-year-old rookie, as well as the reason that Manny Machado and Bryce Harper, both 26 years old, are in line to not only receive enormous contracts, but also return good value for that money. Decades of baseball history back up those claims, and yet they’re counterbalanced by what happened to Jason Heyward.

As a 20-year-old rookie in 2010, Heyward hit .277/.393/.456 for the Atlanta Braves, an impressive slash line in any era, but more prime Jayson Werth than prime Barry Bonds. But for a player his age, Heyward’s performance was historic. Among qualified hitters age 20 or younger, in their first season, Heyward’s .393 OBP was the second highest all time. Here are the six such hitters who posted even a .350 OBP.

OBP Age 25 and Under

Apart from Heyward, that list includes three inner-circle Hall of Famers (Williams, Robinson, and Mays), one Hall of Famer who’d be remembered as an all-time great if he hadn’t retired at 31 because he couldn’t get along with Leo Durocher (Vaughan, and honestly, it’s hard to blame him), plus somebody named Butch Wynegar.

Hayward hasn’t posted an offensive season that good since, but when he hit free agency at age 26—the same age Harper and Machado are now—his career numbers still augured a Hall of Fame future. With 29.8 bWAR and 19.2 wins above average through age 25, Heyward was one of 41 players since 1901 to put up at least 25 bWAR and 15 WAA through six seasons at age 25 or younger. On that list, he was 24th in total bWAR, which doesn’t sound that good, but the 23 players ahead of him included 17 Hall of Famers, two borderline Hall of Fame cases (Andruw Jones and Vada Pinson), Bonds, and three active players (Mike Trout, Albert Pujols, and Mookie Betts).

In November 2014, after five seasons in Atlanta, the Braves shipped him to St. Louis for right-handers Shelby Miller and Tyrell Jenkins. Heyward spent one season with the Cardinals before signing an eight-year, $184 million contract with the Chicago Cubs, which was the largest deal signed by a free-agent position player in the 2015-16 offseason and is tied for the 14th-largest in baseball history. Though the Cubs won the World Series in Heyward’s first year with the club and have been very successful since, that’s as much in spite of him as because of him.

In three years since moving to Chicago, Heyward’s hit just .252/.322/.367. He hit more home runs in 2012 alone (27) than he has total since signing with the Cubs (26). As Heyward entered free agency, his defense, on-base ability, and base-stealing efficiency were always bigger selling points than his power, but even such a well-rounded right fielder doesn’t provide much value without a league-average bat.

As Harper and Machado seek even more lucrative contracts this offseason, it’s worth looking back at the last star their age to reach the open market. Any historical comparison between Harper and Machado on one hand and young free-agent position players of the past, like Bonds and Alex Rodriguez, will dredge up Heyward as a precedent.

So what the hell happened to him? Is there an explanation for how Heyward went from outperforming Frank Robinson as a 20-year-old to hitting like a utility infielder, and does his precedent give us reason to doubt Machado and Harper going forward? There are several possible factors that, taken in combination, begin to explain Heyward’s disappointing performance.

1. Injuries

The two worst seasons of Heyward’s career, relative to expectations, were 2011 and 2016. In 2011, coming off that incredible rookie campaign, Heyward was supposed to take his next great leap forward and become one of the great power hitters of his generation—this was, after all, just after the Marlins promoted Giancarlo Stanton and just before the Nationals promoted Bryce Harper. Heyward was supposed to fit in as the third great young corner outfielder in the NL East.

But in 2011, Heyward hit just .227/.319/.389, and unlike his struggles with the Cubs, there’s an easy and obvious explanation for his sophomore slump: a nagging shoulder injury. Heyward experienced numbness and inflammation in his right shoulder beginning in spring training, and by May 21, with his batting line down to .214/.317/.407, Heyward went on the DL and resolved not to come back until he felt right. But on June 9, his teammate, Chipper Jones, urged Heyward—gently, but directly and publicly—to come back and play through the discomfort. A week later, Heyward returned to action and hit .234/.321/.379 for the rest of the season.

That winter, Heyward said pain from his shoulder injury caused him to pick up bad habits at the plate, and in addition to strengthening the shoulder and improving his overall conditioning, Heyward went to work on rebuilding his swing, and bounced back to hit .269/.335/.479 with a career-high 27 home runs in 2012.

This pattern repeated itself during Heyward’s tenure in Chicago. During the opening week of the 2016 season, Heyward injured his wrist but played through it, and in May he lost a head-on collision with the right-field wall at AT&T Park and suffered an abdominal injury. Neither injury forced him out of the lineup for more than a couple of games, but once again, Heyward suffered through the lingering effects, this time hitting just .230/.306/.325. And once again, Heyward blamed his down year on bad habits developed through injury and tweaked his swing to correct the issues. In 2017, he hit .259/.326/.389, which was still bad for a corner outfielder, but more tolerable than his 2016 performance, particularly considering his Gold Glove-quality defense.

Twice, Heyward has spent most of the season playing through injuries that he says caused him to change his swing. Bad habits developed through injury are nearly as big a threat to a ballplayer as the physical symptoms themselves, the most famous example coming in 1937, when Dizzy Dean suffered a broken toe on a comebacker, changed his mechanics to soften his landing on the injured foot, and blew out his arm. The lasting symptoms of Heyward’s injuries aren’t that severe, but twice now we’ve seen him alter his swing mechanics while playing through nagging ailments, and never quite regain his previous standard upon returning to full health. After the shoulder injury in 2011, he was never again as good as he was in 2010, and after the wrist and abdominal injuries in 2016, he was never again as good as he was in 2015 and before. But Heyward’s physical issues don’t entirely explain his decline.

2. Contact Quality

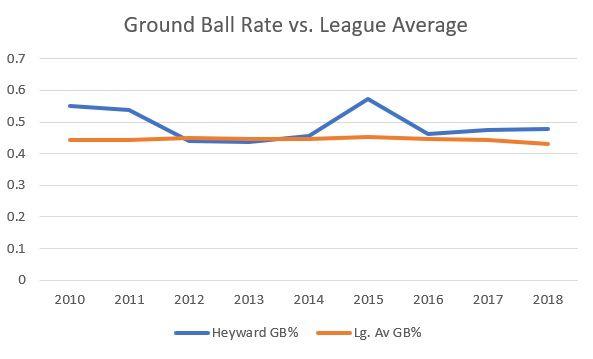

Given Heyward’s size (at 6-foot-5 and 240 pounds, he’s the same size as Ben Roethlisberger) and plate discipline as a young player, it’s frustrating that the raw power he demonstrated then only infrequently translated into games. Specifically, it’s frustrating that Heyward hits the ball on the ground so often. Of 214 players with at least 400 plate appearances last year, Heyward had the 44th-highest ground ball rate. One hypothesis is that Heyward’s ground ball tendencies are the result of that 2011 shoulder injury: that he started hacking down at the ball that year and never got his swing all the way back. The numbers, unfortunately, don’t bear that out. In fact, during Heyward’s best offensive season, his rookie year in 2010, he posted his second-highest ground ball rate.

It also bears repeating that ground balls aren’t necessarily bad—Christian Yelich had the ninth-highest ground ball to fly ball ratio among qualified hitters this year, and he won the NL MVP because when he hit the ball on the ground, he hit it really hard. Statcast-based metrics—exit velocity, barrels, xwOBA, and so on—don’t date back to Heyward’s rookie season, but FanGraphs does have numbers on contact quality for Heyward’s entire career, based on data from Baseball Info Solutions.

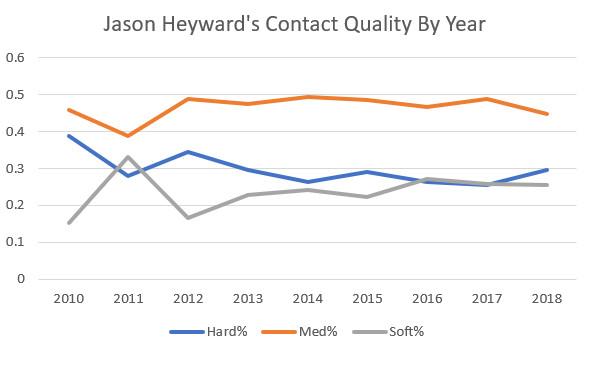

As a rookie, Heyward’s batted ball profile looked a lot like Yelich’s in 2016 and 2017, and you can see the effect of the shoulder injury in 2011 and the bounceback in 2012 before his hard contact rate dropped below 30 percent again from 2013 on. Regardless of launch angle, harder-hit balls tend to become hits more often, and unsurprisingly, Heyward’s BABIP tracks with his hard contact rate.

Heyward’s Hard% and BABIP

The injury-plagued 2011 season stands out, but apart from that, it just seems like Heyward isn’t hitting the ball as hard now as he was in the first and third years of his career. It’s worth trying to figure out why.

3. A Change in Approach

In the same 2017 article in which Heyward told ESPN’s Jesse Rogers about the effect of his wrist injury the year before, Heyward mentioned that he struggled to adjust to hitting leadoff during his later years in Atlanta.

“The more times I led off, the less aggressive I got,” Heyward said. “As a hitter, I wasn’t groomed to be a leadoff hitter, then you’re asked to do it. It was in my head. It kind of never gets out of your head. Passivity comes creeping in.”

It’s difficult to know what Heyward meant by “aggressive” and “passive,” and those definitions matter. Passive, in this case, can’t be a synonym for selective, because Heyward posted his highest walk rate (14.6 percent, sixth among qualified hitters) and lowest swing rate (38.7 percent, 12th-lowest among qualified hitters) in 2010, when he also had his highest BABIP, OBP, and wRC+. Nor is Heyward’s overall swing rate directly tied to his production—he was good with a low swing rate in 2010 and bad with a low swing rate in 2016, and good with a high swing rate in 2012 and bad with a high swing rate in 2017.

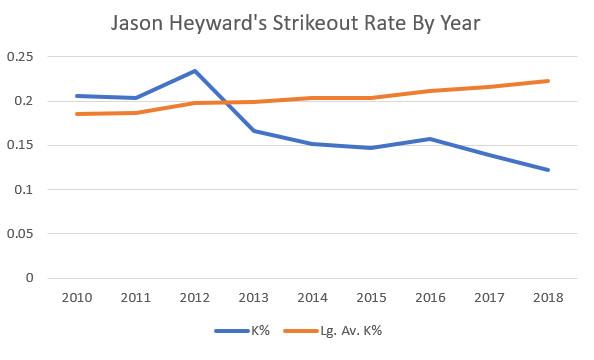

What is interesting, however, is Heyward’s contact rate. The past three years are three of Heyward’s four worst by wOBA, and the fourth was his injury-plagued 2011 season. In the past three years, Heyward’s posted three of the four lowest strikeout rates of his career and the three highest contact rates of his career. As league-wide strikeout rates are skyrocketing, Heyward’s cut his strikeout rate almost in half from his rookie year.

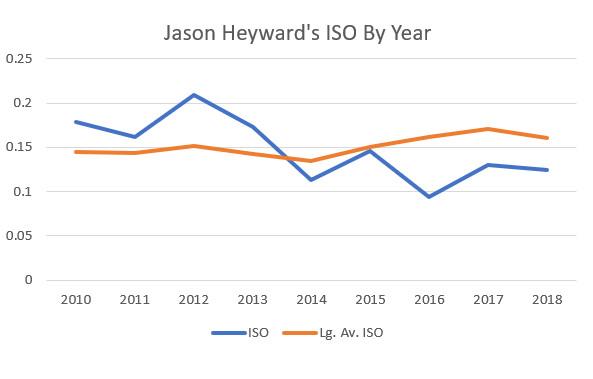

Heyward’s two best offensive seasons, 2010 and 2012, coincided with the seasons during which he struck out the most frequently. They’re also the two seasons in which Heyward posted his highest hard-contact rates, and his two highest isolated power (slugging minus batting average) marks of his career.

Considering Heyward’s marked improvement in contact rate, decreasing strikeout rate, and precipitous decline in power, one obvious conclusion presents itself: Heyward isn’t swinging as hard as he used to. In fact, it’s so obvious it sounds preposterous, but he’s definitely making more contact than ever, to the apparent immense (and paradoxical) detriment of his overall offensive production.

4. Perception

Heyward has always been underrated, somewhat strangely, because of his size. At his peak, Heyward was a great percentage player—a good on-base guy, an extremely efficient base-stealer—and the best defensive right fielder in the game. But because he’s so big, he’s been expected to hit for power, and 2012 notwithstanding, he’s maxed out with home run totals in the teens and a slugging percentage in the low-to-mid .400s. Yelich, who’s tall and broad-shouldered but lean, was viewed as a promising young talent when he was putting up similar numbers, even winning a Silver Slugger in 2016; he didn’t garner serious MVP consideration until his power surge this past year, though. But while those stats worked for Yelich, they were always a bit disappointing for a player with Heyward’s crew cab body type.

But whatever the expectation, Heyward was a reliable five-win player, or better, thanks to his glove and his OBP, and even over the past two seasons, despite taking a step back in both of those skills and hitting for no power, Heyward’s been a two-win player, and roughly league average according to bWAR. A league-average, glove-first right fielder is probably not what the Cubs want from a player who’s made $28 million a season, but considering how little they’re paying Kris Bryant, Anthony Rizzo, and Javy Báez relative to their production, Heyward’s contract isn’t exactly going to bring down the franchise.

The big worry is that while Heyward is still only 29, he’s a big guy with a history of nagging injuries who’s now only an average runner at best. Heyward stole 43 bases in 50 attempts over 2014 and 2015, but he’s never been a burner. Smart players can steal a couple of dozen bases a year without much straight-ahead speed just by picking their spots wisely. (Even Albert Pujols, who runs more slowly than the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice, stole 16 bases in 18 attempts in 2005.) But Heyward’s just 16-for-25 on the basepaths over three seasons in Chicago, and in 2018 he ranked 231st in sprint speed out of 549 players with at least 10 running opportunities measured by Statcast.

What happens if his defense declines to the point where it’s no longer enough to justify playing a below-average hitter in a corner outfield spot? According to defensive runs saved, at Baseball-Reference, Heyward was just six runs above average last year, the worst performance of his career and 20 runs (about two wins) off his career high in 2014. Baseball Prospectus’s fielding runs above average isn’t as down on Heyward’s defense, rating him as an 8.8-run defender, down 18.4 runs off his 2014 career high. One-year defensive metrics are volatile, so maybe Heyward will bounce back, but if he’s a plus-five-run defender now instead of a plus-20-run defender, that’s a problem. And considering that he’s got five years left on his contract, it’s likely that Heyward’s defense will decline further, in which case he’ll be completely unplayable if he doesn’t figure out how to generate some offense again.

Even if Heyward’s defense-forward profile made this outcome more likely, it’s still a shocking offensive drop-off from someone who, even at his worst, was a competent hitter before arriving in Chicago. And it’s all the more saddening because of how much Heyward’s tinkered with his approach and mechanics, and how little good it’s done him.

One might expect that watching the Cubs stare down the last five years and $106 million of Heyward’s contract would give teams pause when considering giving a similar deal to another hotshot 26-year-old. But even though Heyward’s contract, and the age at which he signed it, are in line with Machado’s and Harper’s situations, this year’s top free agents are different enough players that they represent different risks than Heyward did.

Heyward’s struggles, severe as they are, are a stark historical outlier. Throughout baseball history almost nobody that good and that young got this bad this quickly without suffering an injury far more disastrous than what Heyward has played through. It’s also worth remembering that both Harper and Machado are better hitters than Heyward ever was, even as a rookie. His career high OPS+ is 131 and he hasn’t reached 120 in any other season; Harper and Machado have both posted OPS+ marks of 130 or better three times in the past four seasons. That high offensive ceiling should insulate those two from the kind of late-20s drop-off that Heyward’s suffered. Heyward’s contract has turned out to be a once-in-a-lifetime disappointment, and for the sake of Harper, Machado, and the teams that sign them, one would hope it stays that way.