At some point within the next few months, Bryce Harper will smile for the press as he pulls on a jersey at a ballpark to be determined, flanked by bigwigs from whichever team has made him a few hundred million dollars richer than he is right now. The bigwigs will be smiling, too, but somewhere inside, they’ll be wondering what type of player they’ve committed those millions to.

“Anyone who’s done what Bryce Harper has done at 25, if you’ve done that, you’re almost a lock to be a Hall of Fame player,” Harper’s agent, Scott Boras, said earlier this month. Boras also claimed that his client has “great hair,” which was truer when he said it than it is today. But Boras was exaggerating a little less than usual when he asserted that the free-agent outfielder is likely on a Hall of Fame path.

Harper, who debuted in the big leagues at age 19 and turned 26 last month, has amassed 27.4 career WAR, as calculated by Baseball-Reference. Of the 40 retired position players with at least 27 WAR through their age-25 seasons, only 11 aren’t in the Hall of Fame as players, and three of those—Shoeless Joe Jackson, Barry Bonds, and Alex Rodriguez (who hasn’t yet been on the ballot)—are excluded for non-performance-related reasons. Yes, Harper could be the next Vada Pinson or César Cedeño, to name two other outfielders on the non–Hall of Fame list who broke in at 19 but tailed off quickly after age 30. Even they were highly productive players for a few years after age 25, though, and historically speaking, they’re close to the worst-case scenario. In other words, Harper is probably going to be good.

How good is a matter of considerable uncertainty. Over the past five seasons, a span that includes his 2015 MVP year (as well as two first-place finishes in ESPN player polls about baseball’s most overrated players), Harper ranks only 34th among position players in WAR, with 18.6. His recent year-to-year totals suggest that the range of possible outcomes over the course of his next contract is very wide indeed:

2014: 1.1

2015: 10.0

2016: 1.5

2017: 4.7

2018: 1.3

Compare those with the year-to-year totals for the Cardinals’ Matt Carpenter, who ranks next on the list of total 2014-18 WAR with an almost-identical 18.5:

2014: 3.1

2015: 4.0

2016: 3.5

2017: 2.9

2018: 4.9

Harper has been a one-to-10-win player. Carpenter has been a three-to-five-win player. They’ve ended up in essentially the same place, but Harper’s has been a bumpier ride, with a higher high but much lower lows. That’s enough to make any owner nervous (or as nervous as someone can be about one player for a franchise valued in the billions).

The primary culprit behind Harper’s fluctuating WAR has been his offense, which peaked at a 197 wRC+ in 2015—the best in baseball—and bottomed out at 111 (only 11 percent better than the league average) the very next year. Over the past five years, Harper’s wRC+ has risen or fallen by a cumulative total of 150 points. The average cumulative change over all player spans of five years in MLB history—excluding seasons of fewer than 350 plate appearances—is 52, with a median of 45. Harper’s total over the past five years places him in the 98th percentile in terms of offensive inconsistency.

Although Harper’s .330/.460/.649 2015 MVP campaign, which was the most productive per-plate-appearance performance by a qualified hitter since Barry Bonds, may have been a bit deceptive: He overachieved significantly, given where and how hard he hit the ball. Harper has never been a bad hitter; even in a 2018 season that was widely perceived to be underwhelming, he was 35 percent better than the average MLB batter. So it’s somewhat surprising to see him with the same 2018 WAR total as Charlie Culberson and Brock Holt, and a tenth of a win behind 37-year-old José Bautista, who was unemployed until mid-April and cast off by the Braves in May before staving off obsolescence with the Mets and Phillies. Of the 37 players who made at least 650 plate appearances last season, only Rhys Hoskins and Charlie Blackmon finished with lower WARs than Harper.

The cause of Harper’s woeful WAR is the same as it was for Blackmon and Hoskins: a horrific rating on defense. Harper’s minus-26 defensive runs saved—the Sports Info Solutions stat that forms the basis of Baseball-Reference’s flavor of WAR—ties him with Hoskins (and 2011 Logan Morrison) for the 12th-worst total of all time. Other defensive stats have Harper costing the Nationals fewer runs, but he doesn’t fare much better in their ordinal rankings. Harper also brought up the rear among outfielders in UZR and Total Zone and ranked second-worst behind Blackmon in Baseball Prospectus’s FRAA.

Statcast-based metrics were only marginally more kind: SIS’s Statcast DRS, which takes positioning into account, had Harper fourth worst among outfielders, behind Hoskins, Blackmon, and Adam Jones. And MLB Advanced Media’s Statcast-based outs above average (OOA)—which considers range but not throwing—ranked Harper sixth worst among 174 players with at least 50 outfield opportunities.

Sabermetric writers have warned readers about the vagaries of single-season defensive stats for as long as they’ve existed. But when every stat points to a fielder as one of the worst—including stats based on different data sources, some of which (Statcast) are more sensitive and, in theory, more dependable in small samples—there’s probably some signal in the often-noisy numbers.

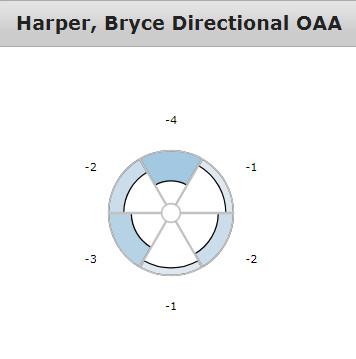

It’s difficult to pinpoint precisely why Harper struggled so much. According to MLBAM’s directional outs above average, Harper rated seven outs below average going back on balls and five outs below average coming in. In every direction, his range was a net negative.

Harper’s problem wasn’t just failing to make the extraordinary plays; he also flubbed an inordinate number of routine plays. Statcast says that Harper converted only 78.3 percent (18 of 23) of his easiest, or one-star, opportunities—plays that are typically made 91 to 95 percent of the time. Only two other regular outfielders completed those plays at a lower rate. Harper’s easiest non-plays, as determined by MLBAM and SIS, give us some sense of how he struggled.

In September, Harper played a zero-star opportunity—a type of play so automatic that it’s not even displayed on a public leaderboard—into a double by Matt Carpenter:

In May, Harper ran into trouble while drifting toward the wall on a Christian Villanueva fly ball:

In July, he had trouble tracking another ball on the warning track, this time off the bat of Starlin Castro:

That problem repeated itself in September against Dominic Smith:

In an August game against the Marlins, he took an indirect route on a liner to center …

... and then let another liner clank off his glove.

He also hung back on catchable balls, including one hit by Amed Rosario ...

… as well as one hit by Jay Bruce ...

... and another hit by Danny Valencia:

In past seasons, Harper’s “Good Fielding Plays” nearly canceled out his errors plus “Defensive Misplays,” as categorized by SIS. In 2015, his misplays-plus-errors outnumbered his good plays by eight; in 2016, six; and in 2017, only one. In 2018, his misplays-plus-errors dwarfed his good plays by 26. Three times, a ball bounced off his glove; three times, he was deemed to have taken a bad route; four times, he was docked for “mishandling ball after safe hit”; and four other times, he was penalized for “failing to anticipate the wall.”

Nor were range and careless mistakes Harper’s only issues. Six times, SIS flagged him for “wasted throws” that allowed a runner to advance, which points to another problem. FRAA and UZR both ranked Harper last in outfield arm runs, and DRS and Total Zone placed him near the bottom of their respective throwing leaderboards. Harper held a career-low 44.8 percent of runners in right field, below the 46 percent average rate for non-Harper right fielders with at least 75 opportunities. In center, Harper’s hold rate—35.1 percent of runners, compared to the 43.7 percent standard among regulars—ranked sixth-worst among 39 center fielders with at least 50 opportunities.

What makes all of this more perplexing is that Harper’s range and arm have historically rated in or close to positive territory. Harper hasn’t been a defensive standout since his rookie year, but from 2013 to 2017, he posted positive DRS marks in three of five seasons, rating 14 runs above average over that span at all outfield positions combined. His arm graded out as an asset in all of those years.

Statcast suggests that Harper’s arm strength regressed in 2018 after a strong showing the previous season. The numbers below, provided by MLBAM, show Harper’s annual ranks in average arm strength among right fielders with at least 10 tracked, competitive throws, with his hardest tracked throw in parentheses.

2016: 24th (96.6 mph)

2017: 4th (99.7 mph)

2018: 16th (96.8 mph)

Late in 2016, Harper played shallower in right field, perhaps compensating for a decrease in arm strength stemming from a reported neck or shoulder injury (which the Nationals repeatedly denied that he’d ever incurred). His full-season average outfield depth dropped from 293 feet from home plate in 2015 to 286 feet in 2016. In 2017, he played deeper (292 feet), which may have reflected a recovery in his health. In 2018, he played even deeper than that (298 feet), suggesting that his arm felt fine, but for whatever reason, his throws didn’t have the same oomph. Despite playing the fourth-most defensive innings of any outfielder, he recorded only one assist, nowhere near his previous low of five in 2016. Of the 70 outfielders who played at least 800 innings, only three others failed to record more than one assist, and none of them played as many innings as Harper.

It didn’t help Harper’s defensive ratings that Opening Day center fielder Michael A. Taylor cratered offensively and rookie Juan Soto cemented himself in left field, which gave manager Dave Martinez more incentive to stick Harper in center. After not setting foot in center field from 2016 to 2017, Harper played 477 1/3 innings there in 2018, by far his highest total since his rookie season. DRS judges fielders relative to the typical player at their position, and in center, Harper had to contend with a more competitive class. The team that wins the Harper sweepstakes probably won’t ask him to play center as often as the Nats did last season, so if his only issue was being unfit for center, his defensive downturn wouldn’t be a big deal. But Harper rated 16 runs below average in right field alone, so the extra time in center doesn’t excuse his stats.

Boras, of course, has an explanation prepared. The agent told The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal that Harper was still feeling the aftereffects of the hyperextended knee that sidelined him for 44 days in August and September 2017. “His legs were flat-out tired,” Boras said, adding, “The rehab time in one offseason sometimes is not enough.” If that were true, one would expect to see a significant decline in Harper’s sprint speed on the bases, but it barely budged, from an average of 27.7 ft/s in 2017 to an average of 27.5 ft/s in 2018. Additional data from MLBAM shows that Harper’s average sprint speed in the outfield—based on the fastest 5 percent of his runs—was also almost unchanged, from 26.8 ft/s in 2017 (29th out of 44 qualifying right fielders) to 26.7 ft/s in 2018 (30th out of 46). It’s possible that Harper was running slower on the typical play, but his top speed was essentially the same, which is probably a positive sign.

Unsurprisingly, Boras projected a return to fielding form for Harper in 2019, telling Rosenthal, “These plus-minus things, when it’s plus-plus-plus all the way through, and then you have a leg injury and it’s minus the next year, it always goes back to the plus.” As FanGraphs writer Jeff Sullivan showed earlier this month, players in recent seasons who’ve suffered big declines in DRS, UZR, and OOA from one year to the next have tended to recover about one-third of their lost value in the season after that. They bounce back, but not nearly all, or even most, of the way. Harper, for instance, declined from a plus-4 DRS in 2017 to a minus-26 DRS in 2018, a 30-run deficit. If he follows that typical trajectory, he’d regain 10 runs next year—which would still leave him at a lowly minus-16.

If every team believed that Harper would be that big a liability in the field at age 26, he might have a hard time finding anyone willing to lock him up well into his 30s, knowing that he’d have to move to DH or first base before long, which would sap some value from his already variable bat. (Boras also indicated that Harper would be comfortable at first.) Yet the Nationals reportedly offered Harper $300 million over 10 years to stay in D.C., so at least one team—the team that watched him all of last season, no less—wasn’t strongly deterred by his defense. Harper, who reportedly declined that deal, is clearly after an even more massive score. And there’s a good reason to think he’ll get it—or that if he doesn’t, it won’t be because of his fielding.

If Harper had lost his top gear, teams would be wary, but when he sprinted last season, he was as speedy as ever. It’s plausible, then, that with free agency approaching and the Nationals (who finished eight games out of a playoff spot) not firing on most cylinders, Harper went a little less than all-out in the outfield this year, gambling that a healthy season would make him more money than a bad defensive season would cost him.

Here’s the most convincing piece of corroborating evidence for the theory that Harper eased off the gas. In 764 opportunities in right field from 2016 to 2017, Harper dove 11 times and slid 17 times, per SIS. In 506 combined opportunities in right and center in 2018, Harper dove one time and slid four times. Among the 21 outfielders with at least 460 opportunities, Harper and Nick Castellanos were the only outfielders not to dive more than once. The other 19 averaged one dive per 60 opportunities. Behold, Harper’s lone dive of 2018:

After that play, Harper appeared to be cradling his hand, a reminder that diving is dangerous. Avoiding that risk may have helped Harper stay on the field. According to Baseball Injury Consultants, 2018 was his first pro season—not counting his nine post-draft games in the minors in 2010—without a single day lost to a reported injury. Harper isn’t hurting for income—he’s already made more than $50 million in MLB salaries, signing bonuses, and incentives alone—but he’s about to be far richer. His impending payday may have been on his mind when he opted not to dive, slide, or crash into the fence in pursuit of balls like this one, which he once might have face-planted to catch.

In 2013, a year when he twice collided with outfield fences—which led to a DL stint and an offseason surgery—Harper defiantly declared that he’d never ease up.

That year, Harper dove 10 times in 314 opportunities, the sixth-highest rate among the 42 outfielders with at least 300 chances. As I later wrote, it seemed then that Harper’s “almost dangerous drive was the only thing that could sabotage his exceptional talent.” By the next spring, though, he admitted, “You gotta be a little smarter. Maybe I shouldn’t have done some of the things I did.”

This year, he didn’t do those things. For Harper, discretion was the better part of defense. We could call that lollygagging, or we could call it putting personal gain before the team. But it might be more accurate to call it being 25 instead of 20 and looking forward to a future beyond the next fly ball.

Thanks to Tom Tango and Mike Petriello of MLBAM for research assistance.