Two points frequently come up when discussing what makes Claire Foy a great actress: One of them is her range, and the other is her amazingly expressive eyes. In an early scene in Damien Chazelle’s First Man, Neil Armstrong (played by Ryan Gosling) comes home to his wife (played by Foy) after someone dies on the job. When Gosling walks through the door, Foy takes one look at his face and—before he says a single word—asks, “Who was it?” It’s a profound performance of intuition that speaks to both these qualities.

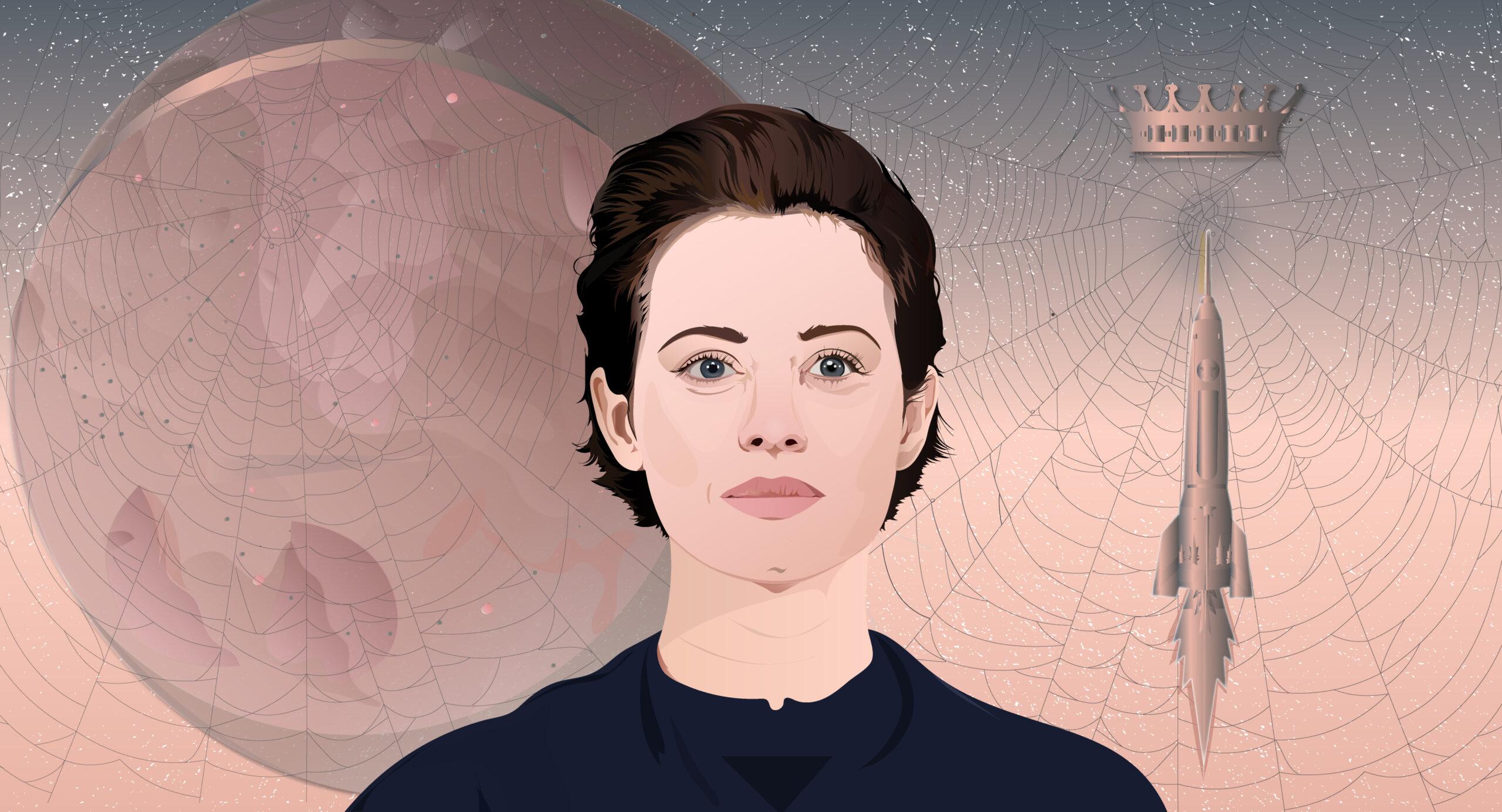

Claire Foy is peaking. Relatively unknown outside England until her 2016 American television debut as Queen Elizabeth on Netflix’s The Crown, Foy has subsequently experienced an undeniable rise. Since 2017, she has consistently won SAG, Emmy, and Golden Globe awards for her performance on The Crown—an arc of prestige that should, in the best-case scenario, catapult her to an Oscar nomination for her recent role in First Man. And indeed, everything this movie season points to a concerted marketing effort in making this happen, from Foy’s multiple American magazine appearances to her follow-up performance as Lisbeth Salander in Fede Alvarez’s The Girl in the Spider’s Web—the second adaptation of Stieg Larsson’s blockbuster Millennium trilogy. There’s even now a Wikipedia page solely dedicated to listing “awards and nominations received by Claire Foy.” No actress, it seems, could be more perfectly primed for Hollywood greatness.

What is more, “The Rise of Claire Foy” coincides with the actress’s transition from a British to an American television and film industry—a transition that, after all, reflects the historical movement of economic world powers. In fact, Foy’s ascension follows the literal movement of empire, from her earlier British period television dramas (Little Dorrit, Wolf Hall, The Crown) to her more recent American genre films (Unsane, First Man, Girl in the Spider’s Web). Even her magazine appearances follow this arc: While Foy was the British Vogue cover girl last November, she currently graces the cover of American Vogue. It’s perhaps unsurprising that Foy is peaking at this present moment of American political uncertainty, given that her performances repeatedly meditate on the precarious decline of previous empires. Part of Foy’s contemporary success is because her roles speak to historical failures. You might call her the actress of the imperial golden age.

It’s not unusual for the rise of an actress to follow the transition from a British to an American film market. It is far less common, however, for that actress to also consistently take on roles that engage the deep historical ambivalences underlying that geopolitical transition. Unlike Keira Knightley, who seems viable in British period pieces about only the posher side of life, Foy’s characters range from the worker (Little Dorrit) to the middle-class (Unsane, First Man) up to, of course, royalty. While Foy’s best performances place her at the center of some kind of power—whether she’s portraying the willful Anne Boleyn in the BBC Wolf Hall or a restrained Queen Elizabeth in The Crown—it’s power always represented as coming with a cost.

The costs are, on the one hand, historic on a mass scale: How many people suffered, for instance, at the hands of Anne Boleyn, not to mention over the course of Henry VIII’s reign? But they’re also made palpably individual through the immediate screen presence of Foy’s own person, which, at 5-foot-4, might arguably be described as diminutive. That is, at least, partly what got her cast as the titular recessive character in the 2008 BBC adaptation of Little Dorrit. And though Foy’s later roles place her in much more assertive—indeed, imperial—positions, the wavering character we find in her early performance as little Amy Dorrit quietly persists. It is this register of her acting range—the one that engages hesitation, reservation, uncertainty—that lends so much depth to her performances of characters who are otherwise known for their sovereign decisiveness.

Foy’s complex performances unsettle the sheen of the classic British period piece, which often present an over-aestheticized view of English history. Instead of glossing over England’s past as one of easy nostalgia, Foy consistently picks roles that remind viewers of how vexed this history truly was. As Anne Boleyn, she is both calculating and determined—a steely portrayal of a woman who’s largely remembered for her ruthlessness. But when the tables begin to turn toward Wolf Hall’s end, Foy lets us see how Boleyn begins to falter, to slacken. The scene of Boleyn’s final execution—during which Foy tremors between proud resolution and utter terror—seems as real and relatable as anything else on contemporary television.

Foy’s next role has her portraying the queen again—this time of a present-day England that is no longer at its imperial height. Though creator Peter Morgan carefully presents the monarchy as a fragile entity, Foy’s performance is key to pulling it off, especially as she plays a young Queen Elizabeth during Britain’s volatile postwar years. The waning of the British empire is embodied through Foy—how she has to manage toggling between the illusion of having power and eschewing it, of being a wife and being the queen. Foy brings all this ambivalence to the level of her face, through her clenched jaw, her darting eyes (OK, so Claire Foy does have amazing eyes). To represent not just a living monarch—but generations of monarchial history—is a tall task. But Foy pulls it off, not by transforming herself into an untouchable walking symbol, but by maintaining the contradictions of what it means to assume power at a moment when that power is also being tested. Claire Foy is the actress of our imperial golden age not because she exudes uncomplicated power, but because her performances carefully walk the contemporary paradox of soft imperialism in our present moment of political unease and rising fascism.

It is perhaps no surprise then that Foy’s current Hollywood peak is exemplified in her performance as the wife of Neil Armstrong in First Man—a movie literally about the myth of American imperialism in the form of the first moon landing. Chazelle critiques the space film genre, the standard narrative of heroic exploration and American ingenuity epitomized in Ron Howard’s Apollo 13. This reassessment of American masculinist conquering is, of course, already signaled in Chazelle’s ironized title: First Man. Of what? While the film is nominally centered on the first man who walked the moon, its larger critique is voiced by that man’s wife—Janet Armstrong, played by Foy. Chazelle draws out every stage at which America’s space race might have failed to remind us that Apollo 11 wasn’t a sure victory so much as a series of contingencies—and no one knows this better than the wives, the mothers, waiting nervously at home. The night before Armstrong leaves for, well, the moon, Foy’s character confronts him and demands that he stop avoiding his children. “What are the chances you’re not coming back?” she asks. “You’re gonna sit the boys down and prepare them for the fact that you might never come home!”

Rather than frame space travel as a transcendent telos about American exceptionalism, Chazelle instead constantly juxtaposes the planetary scale against the more minor registers of the familial. He does this not just by cross-cutting between scenes at the NASA office and scenes at home with Janet and the children, but also through extreme close-ups. If the fantasy of space travel is about scaling up, then First Man undercuts this by quite literally zooming in—and more often than not on the micro-movements lining Foy’s face. Watching Chazelle’s film, you’d believe Foy was cast purely on the amazing blueness of her eyes. It’s a watery blue that acts as a domestic counterpart to the endlessness of the sky. Whereas Gosling’s Armstrong often seems unreachable—both mentally and literally out in space—Foy’s performance grounds the film.

Shot partly on 16mm, First Man exhibits a graininess that helps to index its period piecey–ness as a movie about the American ’60s. Unlike Foy’s other American roles, First Man is more her usual turf because it’s a film about world-historical events as well as the historical hindsight they bring. The graininess of Chazelle’s film, however, also ends up emphasizing the freckles and creases on Foy’s face. They’re the lines of a new kind of contemporary heroine, but also, in a strange way, the lines of a historic face: a face that’s seen the corruption of the English Reformation, the poverty of Dickens’s London, and the waning of the British empire. It’s a face that’s bringing all this history to the surface.

Foy’s other American film roles are similarly pessimistic, though they lack the same degree of critical edge as her period pieces. Both Unsane and Girl in the Spider’s Web are, for instance, about the twinned relationship between misogyny and surveillance—themes that are, in many ways, more urgent issues threatening contemporary American social order. At the same time, these action films give Foy fewer opportunities to showcase what she does best: which is to reflect ambivalently upon the progress of history through performances grounded in restraint. In Unsane and Spider’s Web, Foy almost overacts in comparison to her other roles. In doing so, some ambivalence—some tension—is lost there.

Claire Foy is peaking, and regardless of whether she’ll be able to sustain the hype until the Oscars roll around, let’s hope the stories about her taking a break from acting after Spider’s Web aren’t true. If Foy doesn’t take home an Oscar this season, however, it might be just as well. What could be more appropriate for an actress whose roles are all about uncertainty, loss, and, indeed, even failure?