Three months after the 2016 presidential election, a still-bald Chia Pet in the shape of Donald Trump’s noggin stands on a windowsill in a downtown San Francisco office building, basking in the fog. Art books and an issue of Mother Jones lie stacked on a nearby table. Paintings hang adjacent to a “living wall” of cascading leafy green plants. A receptionist offers coffee, tea, or kombucha, apologizing for being all out of mason jars as she pours water into a glass milk bottle instead. And Tom Steyer, the billionaire hedge fund manager turned political mega-influencer—and long-rumored maybe-someday candidate for elected office—sits in a nearby transparent conference room, ready to rant about emails.

“The emails are coming out on Tuesday,” Steyer says almost as soon as I sit down across from him. He is wearing a tweedy blazer and a primary-colored beaded belt and looks and acts more like a quirky professor than a global financier, more like a guy who’d teach The Bonfire of the Vanities than one of the Masters of the Universe described within. On the back of his hand, drawn in pen, is a Jerusalem cross that sort of resembles a tic-tac-toe board and serves as a tiny visual daily devotional that he says reminds him of humility and faith and also of his four kids. He tends to digress into poetry and/or statistics and/or “did you read that article”s when he speaks, and at the moment, he is asking whether I read that article about the court ruling, one day earlier on February 16, 2017, against Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt.

Pruitt, Trump’s nominee to helm the Environmental Protection Agency, had been ordered by a judge to respond within five days to nine long-outstanding open-records requests for correspondence between Pruitt and his various fossil fuel industry contacts. But it’s all too late, says Steyer: Despite an attempt by Democrats to delay proceedings, the Senate is already in the midst of mulling over Pruitt’s nomination. “They clearly are going to schedule the vote if they can before then,” Steyer says. “Because I’m sure these emails, which are between him and the oil companies, are going to say things that are going to be appalling.” Later, when one of Steyer’s aides looks up from his phone and announces that Pruitt, a man known for suing the EPA, has just been confirmed by a 52-46 vote, Steyer looks pained, but not surprised.

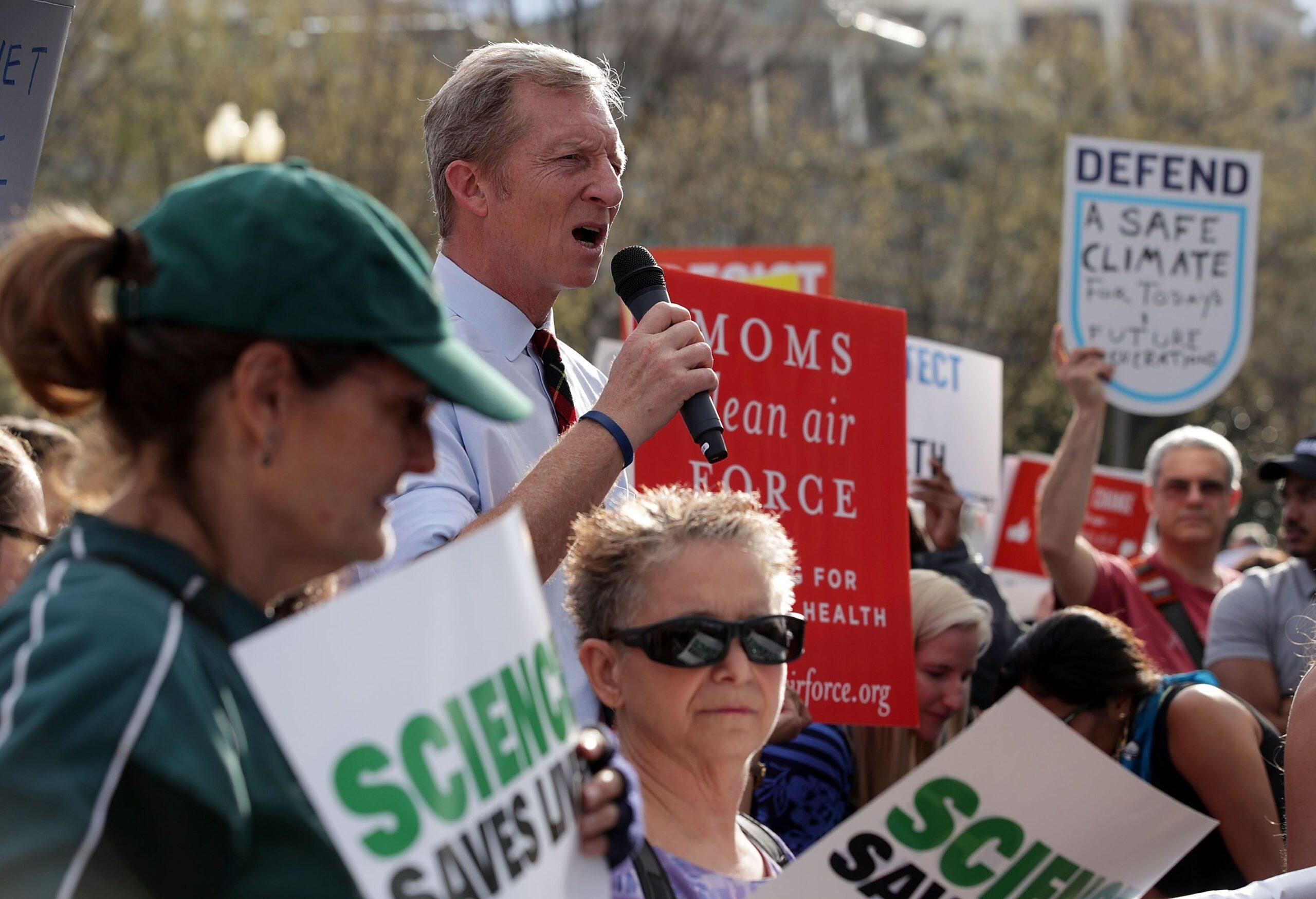

Four years earlier, Steyer stepped down from Farallon Capital Management, the dozens-of-billions-of-dollars-size hedge fund that he had run for more than 20 years, to focus his time and energy on preserving the planet. He launched a nonprofit called NextGen Climate and established an adjacent super-PAC, seeking to target an issue that had been increasingly taking over his thoughts. Steyer carries himself with a sort of paradoxical, headstrong, can-do fatalism, a simultaneous belief that we are basically screwed but also that he can help mitigate the worst-case outcomes. It doesn’t take a hedge fund manager’s gift for data interpretation to be gutted, and even forever changed, by the implications derived from global warming charts. What differentiates Steyer, who is estimated by Forbes to have a net worth of $1.6 billion, is that he also has the monetary and interpersonal means to at least attempt to move the needle, as he has been loudly and relentlessly trying to do for years now.

During the 2016 election cycle, Steyer gave more money to political causes than anyone else in the country, including the mighty Koch brothers. His $91.1 million — an amount that surpassed the $75.5 million he spent in 2014 — advanced his environmental and progressive agenda, securing advertising spots and mobilizing massive voter-turnout efforts around the U.S., particularly on college campuses. It also supported ballot measures, like one that increased the tobacco tax, both within and outside California. And leading up to next week’s midterm elections, Steyer has spent even more, with a target budget of $120 million to buoy Democratic candidates, build and maintain grassroots operations in 13 influential states, deploy a “gray army,” and carry out his year-long, high-profile effort to agitate for the impeachment of the president.

But don’t call him a mega-donor: Whenever Steyer is introduced or described that way, as he often is by interviewers and panel emcees, he will almost always point out that he finds the term misleading. To him, it carries the implication that he’s simply writing the checks, rather than doing the work: traveling the country, engaging in a grassroots get-out-the-vote effort, listening to what regular folks have to say. He likes to point out that NextGen employees and volunteers aren’t just in states like California and battlegrounds like Nevada and Iowa, but that they’ve been there, organizing, for several election cycles by this point, just like their leader himself. Recently, he was deep in the clipboarding trenches at Cal State Fullerton, pestering students and trying to register them to vote. It was a long way away from a past life spent in boardrooms and on Bloomberg, and it was just the way he liked it.

“You can cry in your beer for about two seconds,” says Steyer’s wife, Kat Taylor, as she recalls the night that she and Steyer sat in Sacramento and watched as Donald Trump won the presidency. “And then it was time to get working again.” In one night, Steyer went from anticipating a Democratic White House that he could work closely with to advance his environmental goals, perhaps even from the inside — “I could imagine he would be the secretary of energy in the Clinton administration,” says John Podesta, the former White House chief of staff who ran Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and is a friend and adviser to Steyer — to facing a president with little regard and lots of contempt for Steyer’s thoughts on climate change.

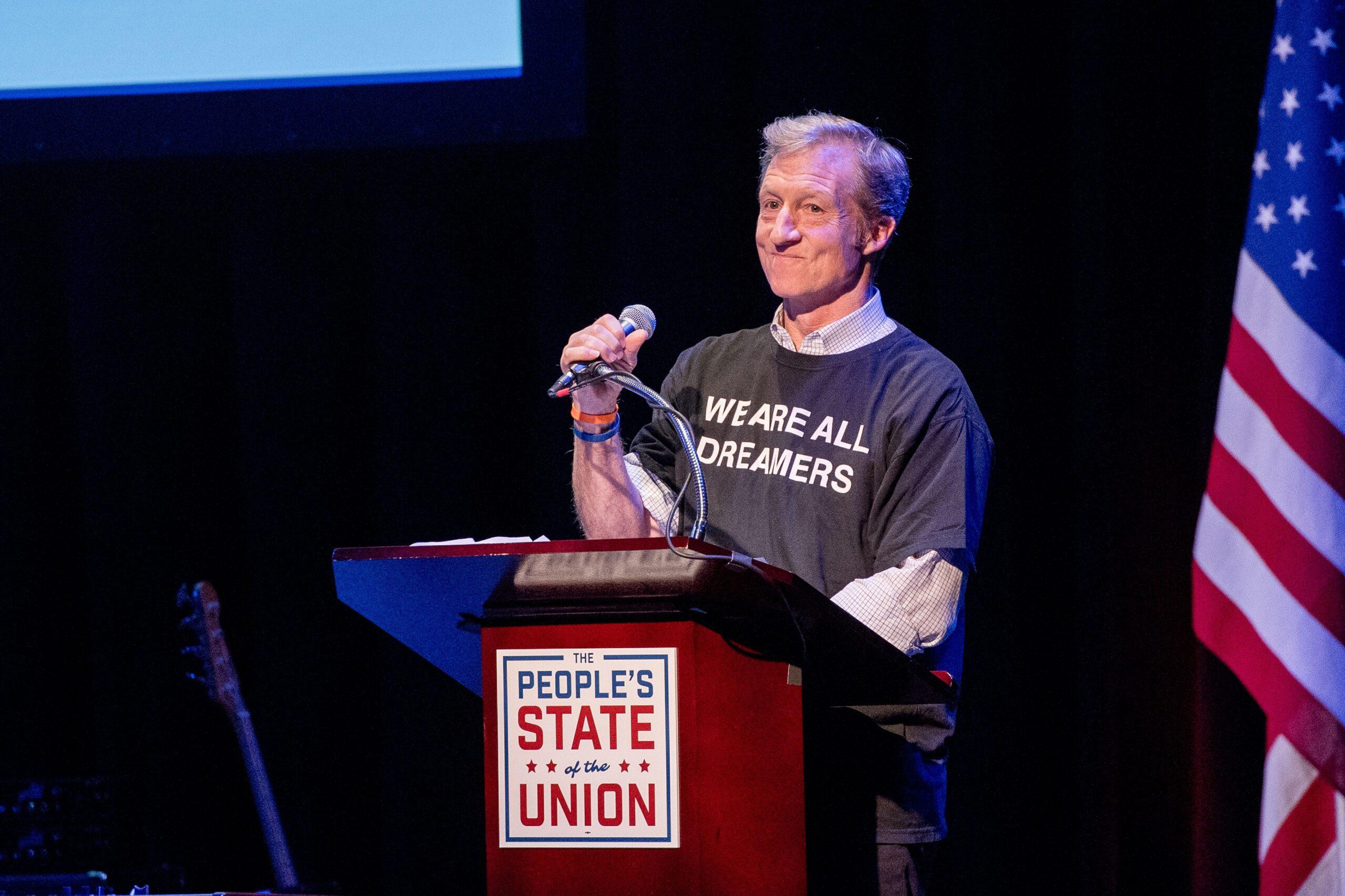

In the months that followed the inauguration, Steyer rebranded NextGen Climate as NextGen America, a tacit acknowledgment of the broadening of the organization’s fight, though he insists that his longtime central mission — not only to battle climate change, but also to promote prosperity and fundamental human rights — has remained unchanged even as words like “impeachment” have crept into his vocabulary. He has kept front-and-center the organization’s mobilization of the youth vote across 419 college campuses. (NextGen’s attention-grabbing tactics have included games of corn hole and extremely good dogs.) So far this midterm election cycle, the organization says it has registered nearly 260,000 people in 13 battleground states to vote. As he had done before, Steyer toyed with the idea of running for major office in California this fall, but determined he’d have more of an impact by using his money and his influence in the coming midterm elections than by engaging in a bitter campaign fight himself. When he’s asked, as he very frequently is, whether he’ll run for president in 2020, his answer is always the same: He’s got his sights set on the midterm elections taking place on November 6, 2018, he tells everyone, and not a day later. (He’ll need to come up with a new response by next week.)

As the midterms near, some of Steyer’s 2018 efforts have already paid off in a big way. One race that Steyer became particularly engaged with was the Florida gubernatorial campaign of progressive, 39-year-old Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, who posted a surprise victory in the Democratic primary in August, which was aided in part by Steyer’s endorsement and by a NextGen voter mobilization effort that included knocks on a reported 81,000 doors across the state. (Gillum thanked both Steyer and George Soros, another hedge funder and Democratic patron whose net worth is an estimated $8 billion, on Meet the Press after his primary win; all told, Steyer has allocated close to $10 million toward the Florida governor’s race.) On September 10, Steyer saw one of his biggest goals come to fruition when California Governor Jerry Brown, a longtime ally, signed a bill and issued an executive order establishing aggressive clean energy and carbon neutrality targets for 2045. As Brown signed the document, Steyer stood just a couple of feet away, wearing one of his trademark red tartan ties.

But other endeavors have proved tougher rows to hoe. An attempt by Steyer to get a clean energy initiative called Proposition 127 on the Arizona ballot was met with ruthless, litigious opposition from Arizona utilities that included accusations of petition shenanigans. (Recently, a judge ruled that the ballot measure would be allowed to proceed.) “Steyer will spare no expense in his shameless bid to buy this election and force his costly, California-style energy regulations down the throats of Arizona families,” said Matthew Benson, a spokesman for a group fighting the measure who frequently refers to Steyer with great derision as “the California billionaire.” This is a common epithet: Jon Thompson, a spokesman for the Republican Governors Association and supporter of Ron DeSantis, the candidate running against Gillum in Florida, said in late September that “by embracing California billionaire Tom Steyer and his unpopular obsession with impeachment, Andrew Gillum is once again demonstrating to Florida voters that his radical campaign is too extreme and too out of touch.”

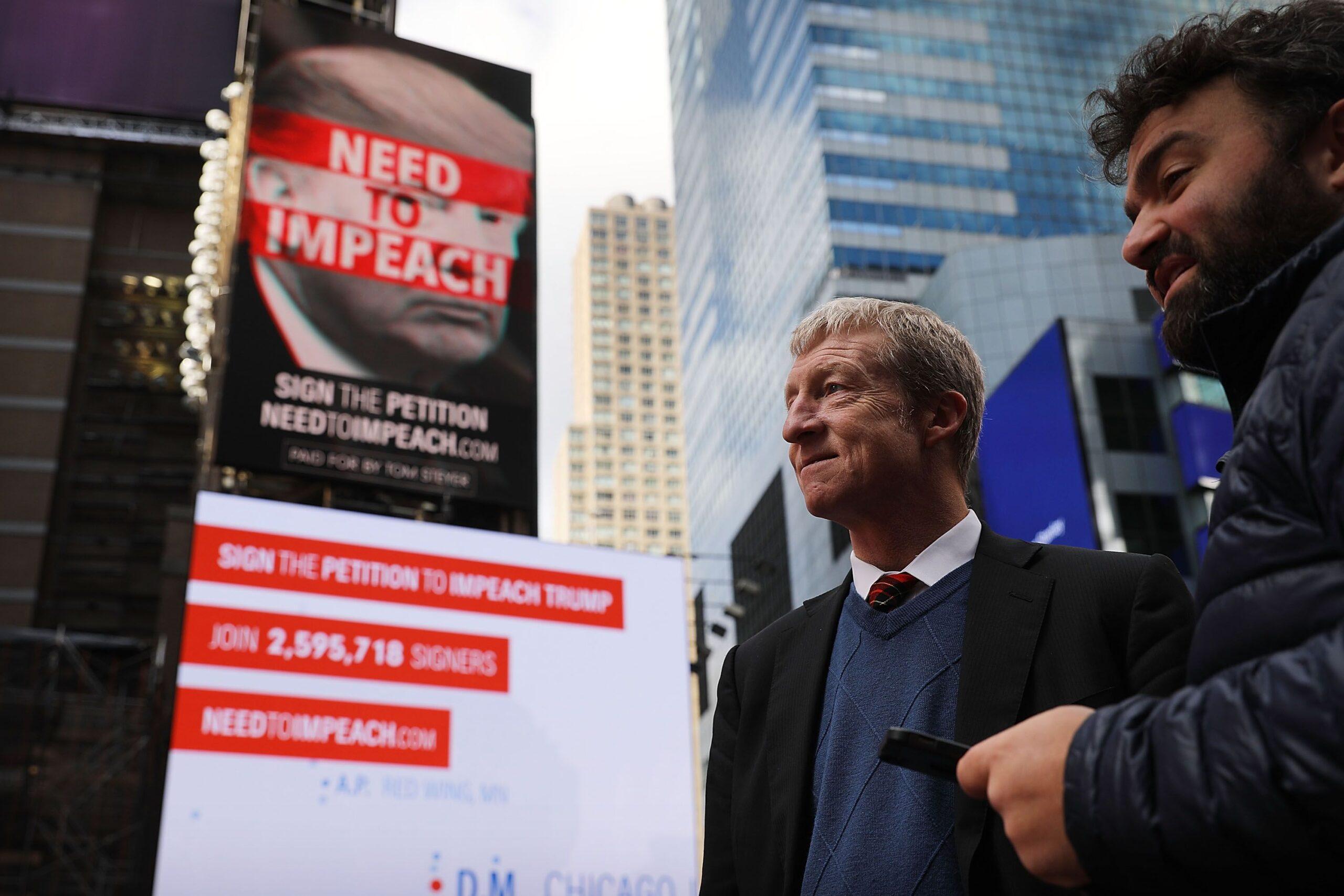

There isn’t much that the DeSantis campaign and the Democratic establishment agrees upon, but Thompson’s characterization of Steyer’s impeachment campaign might be a rare point of union. Looming over just about everything else Steyer has been doing in advance of the midterms has been his straightforwardly named Need to Impeach campaign, Steyer’s most stubborn and solitary initiative yet.

Last October, Steyer spent several million to unroll a series of dour commercials, web videos, and billboards, most of which featured himself laying out the case for such a drastic measure. In the year since, amid the various indictments and convictions and resignations of Trump’s close friends and associates, he has poured a total of $50 million into advertising and voter outreach for the cause. Earlier this summer, when Pruitt became the latest member of the Trump administration to step down from his job in the wake of personal and professional scandal, it was welcome news for Steyer, who had been disgusted by Pruitt’s appointment from day one. But it was also a little bit like the old rude joke about what you call a hundred lawyers at the bottom of the sea — just a good start. As Steyer pursues his zealous mission to reel in the true big fish that is the president of the United States, however, there are a lot of people, even and especially within his own party, who really wish he would stop.

On a hot day in the middle of this most recent June, the 61-year-old Steyer is in Reno, Nevada, sitting inside a hotel that backs up against the Lake Tahoe–fed Truckee River. He woke up in Seattle this morning and will visit Sacramento in a few days, all part of a traveling town hall series pegged to his quest for impeachment. He’s been holding these events on and off since March, with stops ranging from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to Columbia, South Carolina. Between these events and a more recent series of town halls focusing on getting out the vote, Steyer has made 38 appearances this year.

These town halls, combined with televised and digital ads, have positioned Steyer as the face of the movement to run Trump out of office. (Steyer bought ad time on Fox News, but a few days after Trump ostensibly saw the spot and tweeted about “wacky & totally unhinged Tom Steyer,” the network ceased airing the advertisement, citing “a strong negative reaction to their ad by our viewers.”) They have also made him a target: One of the pipe bombs mailed to prominent Democrats last week was addressed to Steyer, which didn’t stop Trump from tweeting about him again, this time calling him “a crazed & stumbling lunatic.” But the Need to Impeach campaign has yielded a powerful tool for Steyer going forward: a still-growing list of more than 6 million signatures supporting impeachment, each a puzzle piece of civic data to be stacked and tracked and pondered by Steyer and his team of number munchers. (It’s also a big, juicy list of people to spam for support should Steyer finally choose to run for office one day.) Steyer says that what makes this list so special is its composition: lots of the people who have signed are not regular voters.

“We have it broken down by congressional district,” he says. “And we know whether they’ve voted. … And 62 percent of them traditionally haven’t voted, because they don’t like the system.” He starts sounding like a hedge funder, rattling off stats and polling numbers and returns on investment, explaining that his team will be able to see “if, in fact, we can convince a reasonable proportion of those people to vote. … That would be super exciting, obviously.” But Steyer is aware that this excitement is not widely shared by the Democrats in Washington. “It’s never been a competition for who wants to lead an impeachment campaign against a lawless president,” he says with a thin smile. “People are fighting not to do it, as far as I can tell.”

This includes Nancy Pelosi, the House minority leader, who also happens to be Steyer’s representative, and who back in April described her pesky constituent’s new campaign as “a gift to the Republicans,” the idea being that a spotlight on such a drastic, pie-in-the-sky measure would do more to mobilize Republican turnout than to boost Democratic engagement. (In 1998, Democrats made gains in the midterm elections as House Republicans began their effort to impeach Bill Clinton.) In addition to the cranky calls coming from inside the House were the ones emanating from Senate leadership: Dick Durbin, the second-ranking Democrat in the Senate, dismissed any talk of impeachment as “not politically viable.” And then there’s David Axelrod, the former Obama adviser who has called Steyer’s initiative “a vanity project” — twice. While there are others in politics, like Gillum, California Representative Maxine Waters, and Texas Representative (and Senate candidate) Beto O’Rourke, who have been more open and amenable to broaching impeachment, Steyer says that “no one else was dumb enough” to put the issue front and center the way he has. His sentiment sounds jokey, but the tone of his voice does not. “Someone had to do it.”

My thesis has always been, Americans can handle impeachment, and [also] the idea that there’s something else that they should be thinking about politically. I think we can talk about two things in the same nine-month period.Tom Steyer

The usual argument against what Steyer is trying to do involves the dismal odds of successful removal from office, which would require a two-thirds majority vote in the Senate, which the Democrats are not widely expected to control. Focusing on such a pipe dream, critics argue, is a self-indulgent waste of time and money that froths up the right while distracting the left, a combination that could cause a double-whammy at the polls. Steyer bristles at all of this, pointing out that the mainstream Democratic unwillingness to say the I-word only further alienates the type of people — his 62 percent — who feel unrepresented by either party and traditionally don’t vote as a result.

“My thesis,” he says, “has always been, Americans can handle impeachment, and [also] the idea that there’s something else that they should be thinking about politically. I think we can talk about two things in the same nine-month period.”

Steyer almost always has a thesis to share; it’s an old habit left over from his former job, when so many investment ideas pitched in so many meetings began with the declaration of a baseline provable premise. Having earned Yale and Stanford degrees and paychecks from Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, where he worked on the once-legendary risk arbitrage desk and earned the esteem of fearsome GS bigwig Robert Rubin, Steyer differentiated himself even further when he left the firm in the mid-’80s to return to the distant shores of California, both to see about a girl (he and Taylor, whom he met while at Stanford, married on the school’s campus in 1986) and to build the business that would make him a billionaire. “Tom was just passionate about California,” Taylor says. “I think it’s his muse, in a way. … I think it captured his imagination and was more of an open field than the protocols and expectations of New York society.”

Having raised about $15 million of capital, Steyer launched what would become Farallon Capital Management in 1986. Named after the rugged, shark-encircled islands off the Northern California coast that for years obscured San Francisco Bay from explorers, Farallon would at one point in 2008 swell to some $37 billion-with-a-B under management, according to The New York Times. Over time, the consistency of Steyer’s returns became the stuff of trading-floor legend; that he operated several thousand miles away from traditional Greenwich Hedge Fund Time and wore denim shirts and flaxen jackets and those red tartan ties only enhanced his anti-slicked-back mystique. According to Institutional Investor, Steyer’s assistant in the mid-’90s once encased his go-to tie in Lucite as a gag; he reacted by going out and buying “several dozen more just like it.”

The youngest of three boys growing up in Manhattan in the 1960s, Steyer was the one who routinely won all the academic and athletic (and the academic-athletic) awards, first at Buckley then at Exeter, as his older brother Jim, a former NAACP lawyer who is now the founder and CEO of the nonprofit children’s advocacy organization Common Sense Media, tells me over the phone with a self-deprecating grumble. (The oldest Steyer brother, Hume, is a New York lawyer.) In college, Steyer made Yale’s varsity soccer team as a defender his junior season and was named captain the following year. He spent summers hiking in the Adirondacks; “picking apples in Alaska one time; that was ridiculous,” Jim says (it was actually Oregon); and working on a cattle ranch in Gardnerville, Nevada, where he took note of what companies made the lion’s share of the equipment so that he could look into buying their stocks when he got home. His father, Roy, was a Sullivan & Cromwell partner who had been involved as a prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials earlier in his career; his mother, Marnie Fahr Steyer, was an educator known to ride her bike up to Harlem to teach literacy to inmates. Steyer describes his mother as “a very American person” who never stood for people getting pushed around; he compares this quality with the early revolutionaries who bristled at living under the heel of the king. Left unsaid is the extent to which he is currently bristling.

Steyer’s early political dabblings were just that: standard-issue, relatively passive campaign contributions to the Bill Bradleys and John Kerrys of the world. But it was about 15 years ago that a Farallon colleague of his named Margaret Sullivan, who had worked in the Clinton administration before joining Farallon as the director of political risk analysis, introduced him to political operatives like Podesta and Chris Lehane, a former lawyer in the Clinton White House, political consultant, and crisis communications specialist. “People think it’s really calculating, that he sort of kept a card file on his Cub Scout troop when he was a kid so that he could run for president someday,” says Podesta, looking incognito in jogging clothes as he sits across from me this summer at a Starbucks not far from his vacation home near Lake Tahoe, where Steyer also has a place. (The two men have spent lots of time wandering together through the nearby national forest, sometimes on snowshoes and sometimes on foot.) “I don’t think it’s calculating at all,” Podesta says, “and I don’t think it’s linear. I think it’s like he goes from place to place, from fight to fight.”

Taylor says that for both her and her husband, the reelection of George W. Bush in 2004 was “a punch in the gut” that left the two of them motivated to find new ways to engage. One of Steyer’s early educations in a more cutthroat flavor of political involvement than attending fundraisers and signing checks came in 2007, when he worked with Lehane to fight a proposed California ballot initiative that would have broken up the state’s monolith of 55 electoral votes. “It’s really hard for the Democratic math to work if you’re not getting 55 electoral votes in California,” says Lehane, who is now the head of global policy at Airbnb, in a phone conversation. “Tom actually got really, really outraged by this. There was money coming in from the other side, and no real coordinated effort in California to address and deal with it. … He came at it almost from a perspective of, like, a moral perspective. Like, ‘This is just fundamentally unfair!’ Like, ‘You’re trying to rig the system!’”

There is an oh-you-sweet-summer-child tone to this memory, but it is also a telling part of Steyer’s activist origin story. Fights like that one, or like his 2010 battle to oppose a proposition that would have rolled back some of California’s air pollution laws (Steyer spent a successful $5 million on advertising and voter outreach to defeat that measure) were what convinced Steyer he needed a more organized and systematic way to counteract the massive sums of shadowy money being deployed by his ideological opponents — a mission that has grown even more urgent, he says, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that lifted restrictions on corporate money in politics. All the while, Steyer was growing more interested in, and alarmed by, both the consequences of global warming and the seeming inability of politicians to address it. “My original thesis was that there was a failure in the American political system,” Steyer says to me, explaining that the whole apparatus has been “hacked” by nefarious special interests. “And then it really — I think that’s turned out to be true.”

On the night of Steyer’s town hall in Reno, near the entrance to the outdoor mall where the event is being held, a small but vocal group of people, some in red hats and most with TRUMP/PENCE signs, mills around on a sidewalk. The chairman of the Washoe County Republican Party is present. One woman holds a hand-written sign that says: “Keep Tom Steyer’s DIRTY money out of NEVADA!” Some of the cars driving by honk in solidarity. “It’s heartening to see that the people who agree with us here today are beeping their horns,” says a Reno woman with short blond hair named Kim Bacchus who says she was “not invited” to Steyer’s town hall. (The event is public, but attendees are asked to provide a name and email to RSVP.) “And it’s amusing to see the old ladies who flip us the bird,” she says. Another man at the gathering, Anthony Magnotta from Minden, Nevada, says that he opposes any talk of impeachment. “Our president is doing an unbelievable job,” he says. “He’s accomplished more in less than a year than anybody in history, going back to Reagan.”

Bacchus says that what upsets her most is the way that Californians — “California billionaires” in particular — routinely think they can meddle in Nevada politics. (Among Steyer’s current causes is a clean energy bill in the state.) “We really are not looking to be California,” she says. “If I wanted to be highly taxed and walk past the homeless that are in record numbers and live in dangerous cities, I’d live there. It gets so bad in San Francisco that kids are stepping on needles and the kids are getting sick from it. It just goes on and on. At one point, four billion in debt. California will never recover.” She laughs. “We were thinking we’ll build a wall between the states.” When Steyer and Karla Hudson, head of community outreach for Need to Impeach, suddenly materialize bearing cups of water, no one makes any real attempt to engage him in debate; everyone eyes one another silently like a bunch of tweens sipping punch at a middle school dance.

California is an effective bogeyman for the right: a high-tax, self-satisfied state that is heavily populated by immigrants, beset by astronomical income inequality and a related urban housing crisis, and often literally up in flames. But it’s also the fifth-largest economy in the world, and to Steyer, it’s a place that “has got to be the positive vision” for the United States, he tells me. One irony of the 2016 election night, he says with a rueful laugh, was that, other than the minor detail of Trump’s election, things went pretty darn well: He and NextGen had been involved in 22 local ballot measures across California, and 13 statewide ones, and the majority of them broke his way at the voting booths that day.

“This has to be the place where we’re going to prosper doing clean energy,” he says. “This is going to be where we prosper with a high minimum wage. This is going to be a place where we succeed in the 21st century, and not try to go back to the 20th century or the 19th century and hope that we can build a wall around ourselves to protect ourselves from the world.” Steyer’s brother Jim, whose Common Sense Media also focuses heavily on doing lobbying and advocacy work within the state, puts it more bluntly: “It’s a functioning democracy,” Jim says. “Whereas Washington is not.”

It’s a functioning democracy. Whereas Washington is not.Jim Steyer

Two of the endeavors most near and dear to Steyer are based in-state: TomKat Ranch, the 1,800-acre experiment in sustainable cattle farming that he and Taylor bought in 2002, and Beneficial State Bank, the Oakland-based progressive community bank he and Taylor launched in 2007 that is now run by Taylor and has 20 branches in California, Oregon, and Washington state. (Hers is a unique leadership: She is a tattooed CEO known to, among other things, spontaneously burst into song, as she did during a keynote at a conference on socially responsible business practices.) Both places speak to the way Steyer and Taylor seek to have an impact: by taking deep dives into areas that relate both indirectly and directly to the climate and have the potential to create systemic change — if they can just figure out how to get everything to work as well in the real world as it does in their minds.

“I guess it depends on how you measure it,” Steyer jokes when I ask how the ranch is doing, his tone suggesting that it has been more labor of love than thriving commercial enterprise. “If there’s a business that’s worse than the cattle business, I want to be introduced to it. But it’s really a giant science experiment about: can we raise cattle in a way that actually reduces the carbon footprint overall. … We think the answer is yes, but that’s a nice theory. Now we would like to see whether it’s true.” Similarly, Taylor says that the genesis of Beneficial State Bank also began with a thesis. “We wanted to run a bank in the system,” she says, “and understand our hunch that something was not going right in the banking system.” Now, she is committed to being a model for socially responsible lending in hopes of changing that status quo. Beneficial State Bank does not provide financing to any fossil-fuel-related projects, she says, adding that the bank pays its employees 150 percent of the living wage. “We had a negative network effect for a long time where everybody thought ‘my bank deposit doesn’t matter and my vote doesn’t matter,’” Taylor says. “And we have to turn both those things around.”

Inside the Need to Impeach town hall event about a half-hour later, the reception of Steyer is unsurprisingly warmer than the one out on the sidewalk. “First, I’d like to say: It’s wonderful to have someone with the money and the balls to do what you’re doing,” says a concerned citizen who stands up and identifies himself as Dave. Dave doesn’t specify precisely what he means by “what you’re doing” — whether he is referring to the Need to Impeach tour, or to the stressful TV ads, or to Steyer’s more general life trajectory from quiet hedge fund titan to outspoken political activist. But like most of the other 200-plus people in attendance, Dave appears to be hoping that Steyer can give him some of the answers for which he has spent the better part of the last two years searching.

“It’s very difficult to stream into a few words this reservoir of hatred,” he says, taking a deep breath and drawing sympathetic chuckles and hoots, before getting to his question: “If we do not achieve the proper majorities to impeach,” he asks Steyer, “is there a legal recourse after that? Or are we screwed?” He sounds righteous but bewildered, like a wrongly accused man conferring with his lawyer, pleading that surely something, anything can undo this unnecessary mess.

Steyer’s response is accurate, but like so much of the conversation around impeachment, it’s also obvious and a little uninspiring. The solutions in that case, he says, would mostly revolve around getting out the vote, electing like-minded representatives, and trusting in the courts — basically, just politics as usual. For all the Democratic worry that the subject of impeachment is too hot to handle, in reality it’s not exactly a topic that brings out the hype: the words “we asked 58 constitutional scholars to identify the high crimes and misdemeanors and posted it on our website” is not the stuff of bumper-sticker slogans. Still, the audience seems thankful to be discussing it at all.

An older woman stands up to speak as well. “I appreciate this,” she says, her voice cracking almost immediately, “because I feel so exasperated!” She takes a shaky breath. “I didn’t think I’d cry!” she says. “There are some things we need to do now, that can’t wait until the election! I’ve made phone calls and written letters until I’m blue in the face, and I can’t get anybody to listen to me!” Steyer nods. “We have a hole in our heart,” he says. “We have 5 million people”—now 6 million—“who signed our petition, people who feel the same way: the same patriotism, the same compassion toward human beings.” He makes namaste hands, and talks about the arc of history bending toward justice.

I think there’s nobody more zealous than the recently converted.Kat Taylor

“There’s an almost religious-like element,” says Jim Steyer. “There’s definitely a missionary element to my brother now.” When Steyer had kids he began going to church more often “to introduce them to the idea of the almighty,” he told Rolling Stone. While he was there, he found himself interrogating his own concepts of morality, service, and higher purpose. (He remains a regular worshiper at Grace Cathedral.) “I think there’s nobody more zealous than the recently converted,” Taylor says about her husband. She is actually talking specifically about Steyer’s love for California when she says it, but she could easily be speaking more broadly about the way he has lived his life of late.

Andrea Johnson hadn’t heard the name Tom Steyer in about a decade. Then she started getting calls from political reporters. As a grad student at the Yale School of Forestry in the early aughts, Johnson had been one of the leaders of a movement, called UnFarallon, that sought a greater level of disclosure and transparency around the underlying investments held by the university’s best-in-breed, then–$12 billion endowment. Overseen by industry legend David Swensen, one of Steyer’s dear friends, the Yale Investments Office doled out its funds to a number of outside money managers, private equity firms, and hedge funds, including Farallon. A labor union dispute between Yale and university workers a few years earlier had kicked up an opposition research campaign that uncovered Yale’s involvement alongside Farallon in the controversial purchase of Baca Ranch, a plot of Colorado land sitting atop an aquifer that the investors sought to tap into in order to divert and sell water to the Denver suburbs. Johnson wasn’t part of the union, but as an environmentalist she was dismayed to hear about Baca Ranch and the damage the plan might do to the local landscape. How many other similar deals were taking place all the time that no one knew about? She wasn’t alone: Students from other institutions with opaque endowments, including Stanford, Duke, and Penn, would eventually join in the UnFarallon cause.

Johnson was slightly skeptical to learn, years later, that the man behind Farallon was suddenly a mover and shaker in the environmentalist world. But she was pleasantly surprised to read that the UnFarallon movement had registered in some way with Steyer. (Taylor told Men’s Journal that the whole situation was “a little flare going off in our minds” and that it led the couple to strive to one day become “totally aligned” between their personal politics and their professional actions, although it didn’t happen right away.) Yale and Farallon ultimately abandoned the project and sold the land, and in 2005, Steyer admitted to Institutional Investor that “eventually, we got it through our thick skulls that we were not going to convince anyone” of the logic behind some of their investments. Johnson, who now lives in Costa Rica, laughs when she thinks about how her youthful activism manifested then and endures now. “There’s students standing outside the endowment office, like, smashing a papier-mâché globe,” she says, sounding how anyone might if asked to re-live their ol’ collegiate exploits. “I’m dressed up as the ‘UnFarallon fairy.’ It was ridiculous activism. And now you’re like, wow … talk about the butterfly effect, right? You never know.”

The UnFarallon episode is illustrative of a bigger, and more existential, question that continues to dog Steyer: Can he ever really shed his reputation as just another privileged progressive, a limousine liberal, a member of the coastal elite, a California billionaire nosing around in other people’s lives? No one would bat an eye if Steyer were the kind of hedge fund billionaire whose political passions included tax cuts or regulatory loosening; there’s no hypocrisy to be mined in that. But a wildly rich guy who sends his four kids to Stanford, Harvard, and Yale, inhabits an enormous manse on a cliff overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, and talks a big game about helping the little guy and saving the environment? That’s catnip for the opposition.

“You know,” Lehane says, comparing Steyer to another rich New Yorker who had big ideas, “they called FDR a traitor to his class.” He says that for a long time, Steyer and Taylor have thrown a big birthday party every summer at their TomKat cattle ranch. Lehane first started attending around 2004. “And at that time,” he says, “it was probably larger than the economy of France, just in terms of the net worth of the people who were there.” Over the years, though, as Steyer’s interests have evolved, so too has the cast of characters at the parties. “As he’s gotten more involved in the political process,” Lehane says, “you’ve seen the whole mix shift. Now it’s like a modern-day Village People. It’s like a Woodstock out there. It’s a blast.”

Steyer says there was no one epiphany that altered his worldview, but he identifies a few smaller influential moments. He credits a “very inspirational” friend who is an Episcopal priest with helping him to “take a much broader view of life” as he began attending church more in the early aughts. In 2007, when he was named to the Board of Trustees at Stanford, he did some thinking about what a modern university could address in order to make a difference in the world and realized the answer was climate. Before the last election, it was almost unfairly easy to denigrate his work and question his sincerity in one fell swoop simply by pointing out that some of his riches could be linked to old Farallon investments in fossil fuels. “You made a whole lot of money in oil, gas, and fossil fuels before you decided you didn’t like oil, gas, and fossil fuels,” remarked the host of Marketplace in a 2015 interview. “Sure, I changed my mind,” Steyer responded, “because the facts became clear that we had a big problem, we weren’t dealing with it, and it was up to citizens to change their mind and take action.” Steyer seems to understand that the only way out is through; he doesn’t try to hide from his past as he seeks to influence everyone’s future. “I think you rarely meet anybody who changes their mind in life,” says Taylor. “Like, most people kind of dig in, and Tom’s the most remarkable human being to me because he just started changing his mind on a lot of fundamental things and taking action on it.”

Steyer’s focus is broader now; he speaks about things like stagnant wages and public health in addition to oil pipelines and clean water. When he does, he is careful to acknowledge his own privilege and make clear his desire to effect change that can give others access to the kind of opportunities in life that he’s had. This isn’t a brand-new tactic on his part, either — it’s something he’s considered for a while. In September 2008, during the early days of the recession, Steyer made comments to Fortune that were a preview of his developing ethos toward what he considered to be the myopia of many of his fellow successful, wealthy-beyond-belief investors.

“There is definitely a strain in American capitalism,” he said then, “where people believe that they have made the money on their own, basically working single-handedly as an individual to create wealth for themselves. I completely disagree. … I mean, they are the beneficiaries of literally over a thousand years of people creating a system and sacrificing.”

“The Lucky Sperm Club” is what Warren Buffett, who has long been a hero of Steyer’s, likes to call it: that great genetic and celestial crapshoot that distributes privilege and opportunity wildly unevenly and enables some people to amass $85 billion, as Buffett has, while ensuring that others may never catch any break. (In a nod toward equality, Buffett sometimes calls it the “Ovarian Lottery” too.) Acknowledging the role of randomness in his success is something of a departure from the more social-Darwinist spirit of past titans of industry like Andrew Carnegie, the steel baron who wrote a treatise called The Gospel of Wealth and who, in a speech in Pittsburgh, explained why it was better for him to use his money to build public cultural and research institutions rather than pay his workers more. “Trifling sums given to each every week or month,” Carnegie said, “would be frittered away, nine times out of ten, in things which pertain to the body and not to the spirit.”

But in some ways, the net result of both men’s philosophies are the same: both agree on the importance of significant, thoughtful philanthropy. It’s just that while Carnegie believed that it was his duty to give back because he was special, Buffett at least makes it sound as though it’s his duty to do so precisely because he knows he is not. In 2010, Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates launched an initiative called The Giving Pledge in which, essentially, a whole lot of rich people wrote IOUs backed by a sort of moral honor code, agreeing to enthusiastically give away the lion’s share of their personal wealth over their lifetimes. Steyer and Taylor signed the pledge that year; so, too, did others with orders of magnitude more money than even they have. And so, having long ago achieved what-do-you-get-for-the-man-who-has-everything status in life, Steyer continued to fixate on a different question: When you’re the man who has everything, what do you give?

A couple of years later, Steyer found one of the clearest answers to the question yet. “Did you read it?” he asks me, referring to the 2012 polemic that the longtime environmental activist Bill McKibben wrote for Rolling Stone about the doomed math underlying climate change broadly and the Keystone Pipeline specifically. (Steyer loves McKibben: “He cuts through all the chaff,” he says. “You read his stuff and it’s like, wow. Did you read his thing on Justin Trudeau? You should read it. It’s sort of like, OK, that’s the end of Justin Trudeau! I’m never going to take him seriously again, that’s for damn sure. Just like, boom! Done!”) McKibben’s 2012 Rolling Stone piece methodically calculated the threshold of carbon output that would keep the planet’s temperature from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius — and then made the case that the amount of fossil fuel reserves held by large corporations and oil-rich nations, if utilized, would release five times that amount. “It was a seminal article,” Steyer says. “So I just called him up and I said, ‘Look, you don’t know me …’”

One thing led to another, and soon the two men were on a hike in the Adirondacks, not far from McKibben’s home in Middlebury, Vermont, an area that Steyer knew from trips growing up. They parked McKibben’s car at one end of the trail and Steyer’s at the other, and climbed up and down two little mountain peaks. At the top of one, they chatted with a father and daughter from D.C. who were about to cut their planned hike short in order to have time to double back to where they had parked; by the end of the conversation, McKibben had insisted upon giving them his keys so they could complete their trek and drive back to their car.

“I’m like, OK, this is a different kind of guy,” Steyer says about McKibben. “Because, working in investments, the last thing in the world that is ever going to strike you is, you know, here’s a couple thousand bucks, and I’ve never met you, but I think there’s a hell of a chance you’re going to give it back to me.” Steyer was extremely touched by the gesture. “You know, he teaches seventh-grade Sunday school,” he says of McKibben. “He’s a really smart guy, but he’s a really good person. And I really enjoyed both parts of him. His big brain and his very warm heart.”

In an email, McKibben tells me that he is currently on the Greenland ice shelf with no cellphone service and only intermittent Wi-Fi, though he confirms the details of Steyer’s fond memory. (He isn’t the only one to respond this way: Matthew Barger, one of Steyer’s Yale soccer teammates and later business partners, emails me back to say that he is in Mongolia with limited access to the internet.) “I’m prepared to dislike billionaires,” McKibben adds. “So I was surprised to find out he was a stand-up genuine good guy.”

This was a life-defining hike for Steyer, who, after communing with McKibben, came away with both a deeper concern for the planet and some specific ideas for what to do about it. He stepped down from Farallon in January 2013; demanded in March of that year that a Massachusetts senatorial candidate denounce the Keystone XL pipeline “by high noon on Friday” or else he’d donate to his opponent; hosted a Democratic fundraiser at his home that April in which he hectored the newly reelected President Obama about the pipeline as well; and launched NextGen Climate later that year. He also spent a reported $8 million opposing a climate-denier gubernatorial candidate in Virginia, money that included hiring a plane to fly a “Cuccinelli Says Go BYU” banner over a UVA-BYU football game.

“He’s apocalyptic about climate change,” says Podesta, adding that Steyer’s recent focus on impeachment is less of a pivot than it is an entrenchment. “I don’t think he’s moved on from climate; I think he’s concluded you can’t fix climate unless you fix politics. All the bipartisan ideas about a carbon tax in the world don’t matter unless you can fundamentally put people into office who understand.”

I think he truly believes that we can lose the country.John Podesta

And when it’s framed that way, Steyer’s uncompromising stance on impeachment starts to make more sense too. If one believes, as Steyer does, that Trump has met the standard for impeachment — that he’s unfit for office, a liability, a threat not only to the country he supposedly leads, but to the stability of the whole damn planet — it’s not really an option to kick the can down the road. “I think he truly believes that we can lose the country,” Podesta says. Last fall, during a trip to Germany for a climate conference, Steyer and his daughter visited Nuremberg, where his father had once worked. He came back more certain than ever that he could not afford to give up on impeachment, says Lehane. “[He] talked about what his dad had talked about having learned being a prosecutor: that you have to stand up on issues that you care about, that are profoundly important.”

If Steyer’s stance on impeachment feels like just a dramatic diversion based on a procedural near impossibility, it’s nothing compared with the changes he wants to make to the Bill of Rights. Earlier this year, at California’s state Democratic Convention, Steyer delivered a speech in which, among other things, he floated the idea of establishing a new set of constitutional rights, including the right to affordable health care, the right to clean air and clean water, and the right to free public education and technical training. “The way he’s looking at things is: current system establishment does not work,” says Lehane. “Current political process is corrupted. … As opposed to thinking that you’re going to win by playing small ball, why not go big and add rights to the Constitution? Those constitutional rights then by definition create a different accountability and responsibility framework.”

Lehane sounds exasperated over the phone when I mention Axelrod’s repeated assertions that what Steyer is doing is a “vanity project.” (Axelrod did not respond to an email asking him to elaborate further on his views, but in May he told New York that “if we begin to use impeachment as a political tool to erase public officials — presidents — we dislike, or whose policies we dislike, then once you go down that road, you can’t put the genie back in the bottle. It becomes the norm, that’s my concern.”) A vanity project for a billionaire, Lehane says, would be going out and buying a sports team. “Right? What I’d do,” he says; indeed, it is what another hedge fund tycoon, David Tepper of Appaloosa, recently did when he spent $2.275 billion on the Carolina Panthers. “Deciding to spend a bunch of money trying to organize typically underrepresented people to vote?” Lehane says. “This is the first-ever time that would be described as vanity.”

He’s like a lightning rod of hope. He’s giving us a voice. We’re just a drop of water. He’s a bucket.Cindy Norris

Following the town hall, Steyer mingles with attendees, nodding indulgently and making eye contact as they burden him with the details of their lives. The woman who had started crying earlier has stuck around to meet him. “I signed the petition and so I got an invite to this in the email,” the woman, Cindy Norris, tells me. “He’s like a lightning rod of hope. He’s giving us a voice. We’re just a drop of water. He’s a bucket.” Steyer meets with a small group of Nevada-based NextGen organizers, posing for photos and thanking them for their work. As one girl leaves the building, she makes a call on her cell. “Mom,” she says, “I just met Tom Steyer!”

It has the feeling of a campaign rally, and maybe one day these sorts of appearances will be. Sometimes it’s difficult to imagine Steyer making true headway as a national candidate; he’s unpolished and can be dry; he’s a California billionaire who used to profit from fossil fuels; he’s that guy from the impeachment commercials and is currently not exactly a beloved figure by many Democrats as a result. “My attitude,” Steyer tells me at the Renaissance hotel earlier that day, “is I’m trying to do something I deeply believe in, and I’m aware that it’s going to threaten the interests of powerful, nasty people. And they’re going to respond in powerful and nasty ways. It’s like Australian rules football. If you walk by, and you give them a chance, they’re going to elbow you in the nose.”

When I ask whether he’s been elbowed in the nose lately by people who should ostensibly be his allies, he says: “You know, if the Mercers don’t like me, it’s sort of like, yeah, I didn’t think you were going to really like me, because by the way, I don’t like you either. I think bullets in the back are always more painful. But I think at this point, it’s a question of defining who it is you’re trying to have a relationship with, and be clear about what you’re trying to get done.” Steyer has long made his priorities known and supported the people who are on the same page; in the upcoming California senatorial race he has endorsed state Senator Kevin De León, with whom he has worked closely on establishing cap-and-trade policies in California, over longtime stalwart Dianne Feinstein. (De León has ripped the senator for being “someone who has lived in a mansion surrounded by walls all her life.”) In 2015, when Podesta castigated Steyer in a profanity-laced, hacked email for implicitly calling on then-presidential candidate Clinton to commit to eliminating greenhouse gases by 2050, Steyer coolly responded with polling numbers supporting his case.

I’m trying to do something I deeply believe in, and I’m aware that it’s going to threaten the interests of powerful, nasty people. And they’re going to respond in powerful and nasty ways. It’s like Australian rules football. If you walk by, and you give them a chance, they’re going to elbow you in the nose.Tom Steyer

I linger to ask Steyer a question that’s been on my mind for a while: Is there a significance to his colorful beaded belt? And of course there is: The short answer is that it was made by Maasai women, and Steyer acquired it while visiting Kenya to look at a school supported by a friend of his. The long answer involves a book recommendation (Drawdown, by Paul Hawken, with foreword by Tom Steyer); a gloomy attempt to make sure I grok the severity of the title (“drawdown, like we’re going to actually have to remove carbon from the atmosphere,” Steyer says, looking me in the eye); an affable but mildly gaffe-y aside that would probably get chewed up and spit out on any campaign trail (“I’m 99 percent a parochial American,” Steyer says, proudly, “but 1 percent I believe that educating girls around the world is an unbelievably powerful important moral thing to have happen”); and a mini sermon that sounds a lot like a thesis.

In Drawdown, Steyer explains, there are a hundred different solutions outlined that can help reduce global warming. “And I think, like, numbers 3 and 7 out of 100 are about the education of girls, and about birth control,” he says. “It’s like, boom! If you combine the two of them, it’s the most important thing for climate. But it’s also about justice, and treating people fairly.” Listening to him go on about this, his hands flailing wildly and his voice gaining speed, it’s hard to subscribe to the “vanity project” theory, or to ascribe ulterior motivations for the work Steyer does. He may be an extreme annoyance to Beltway Democrats, and he may be despised by President Trump, but in person, Steyer is just an earnest nerd, a passionate eccentric, a tireless competitor. An aide gives him a head nod; it’s time to go. Steyer turns back to me. “So, I wear a nice belt,” he says, and heads off into the hot night toward his next stop.