“What are the balloons for?” asks the guy holding the camera, marveling at a lengthy row of inflatable stars in red, black, and silver as he trails Lady Gaga up a winding staircase in her spartan Malibu mansion. “Uh, Warner Bros. greenlit a movie that, uh, Bradley Cooper’s directing,” Gaga replies. “And Bradley wanted me to be in it. A Star Is Born. And, um. You know. I’m gonna star in the movie.”

This exchange occurs a few minutes into the 2017 Netflix documentary Gaga: Five Foot Two. And it is quite remarkable—given that this is a movie about a famous pop star recording and releasing yet another no. 1 album, and then rehearsing and performing her own Super Bowl halftime show—how preposterous those words sound as Lady Gaga speaks them. Another A Star Is Born? Greenlit? “Bradley”? Is she serious? She can’t be serious. This feeling persists even from the vantage point of October 2018, with Bradley’s A Star Is Born a genuine sensation, and Gaga herself a multi-statue Oscar contender, and the soundtrack netting her yet another no. 1 album. Captured on film in that bygone moment, coolly describing a ludicrous new project that turned out to be 100 percent legit, she still sounds delusional, somehow. But like all great pop stars—and all great pop star documentaries—she details her delusions with such conviction that she can’t help but make them real.

A Star Is Born has reignited age-old arguments about authenticity and rockism, and how a genuine pop star sounds and dresses and acts and should be made by “real” musicians to feel. This conversation is available in think piece form and also meme form. The short version is that Gaga’s character, Ally, comes off in spots like a “bad” pop star, vapid and compromised, in what amounts to a wayward critique of the actual Lady Gaga’s actual pop star career. Our old pal Bradley seems a little confused as to what this music—what this job—entails.

Which makes this a fine time to revisit Five Foot Two and other recent pop documentaries of its ilk, starring Gaga’s various peers and competitors. In August, Apple Music debuted Songwriter, a low-key Ed Sheeran vehicle that might win over even the steeliest Ed Sheeran hater. In October 2017, YouTube premiered the gnarly but charming Demi Lovato: Simply Complicated, an uncomfortable rewatch in light of her ongoing recovery from a reported drug overdose this past July. Other present-tense stars have already entered the canon, including 2013’s HBO premiere Beyoncé: Life Is But a Dream, which followed 2012’s Katy Perry: Part of Me and 2011’s Justin Bieber: Never Say Never, both released in theaters, in 3-D.

None of these quite crack the modern rock-doc pantheon, occupied by the likes of Madonna’s arty 1991 provocation Truth or Dare or Metallica’s spectacularly ill-advised 2004 therapy session Some Kind of Monster. And it’s true that these movies age in dog years at best—just as your new car depreciates the second you drive it off the lot, an intimate look at a superstar can date itself horribly before your very eyes as new real-world triumphs, tragedies, and calamities ensue. And as much as these docs offer backstage access and whispered confessions and an almost invasive sort of vulnerability, they can be as contrived and tightly controlled as any corporate-heavy album rollout. You are never eavesdropping; you are never seeing anything the pop star in question doesn’t want you to see.

But the end products can be revealing and even revelatory, all the same. “This is me with nothing,” Gaga intones deep into Five Foot Two, talking up her stripped-down 2016 album Joanne. “I don’t need to have a million wigs on and all that shit to make a statement.” And soon she’s in a medical paper gown, describing her chronic hip pain to a doctor, turning the examination table into yet another stage requiring yet another fantastical costume. As always, you know it’s a performance because you’re watching it.

The “aging in dog years” aspect is no joke. Justin Bieber: Never Say Never is a mere seven years old, but for current insight into modern pop stardom—hell, for current insight into Justin Bieber himself—you might as well be watching a Charlie Chaplin movie. Directed by Jon M. Chu, the 2011 film, which made just short of $100 million in theaters worldwide, chronicles our boy hero’s rise from pint-sized Canadian YouTube sensation to floppy-haired 16-year-old dreamboat selling out Madison Square Garden; the big climactic number is his preadolescent 2010 smash “Baby.” There is zero conflict or tension, save a slight blip when young Bieber, the lovable little scamp, imperils his arena tour because he just can’t stop taxing his voice by horsing around on the basketball court with his lovable Canadian childhood pals.

That’s it, in terms of bad behavior. Seriously. This movie is rated G. It is hilarious to revisit this in 2018, given how delightful it would be to convene his various managers and handlers—all of whom sing his wholesome praises onscreen—and show them even a 90-second highlight reel of the next seven years in the Justin Bieber experience, from the bucket to the monkey to the Anne Frank thing and far beyond. Simpler times. Here he is adorably flipping his hair in slow motion.

Beyoncé: Life Is But a Dream, from 2013, also documents far simpler times and struggles with its star attraction’s fundamental disinclination to show weakness or express credible self-doubt or relinquish even an iota of control. For example, it is directed by … Beyoncé Knowles. “I always battle with how much do I reveal about myself,” she concedes, sitting regally on a couch and batting away interview questions that aren’t so much softballs as delicious wads of cotton candy. It’s not much of a battle.

The usual pop-star-documentary staples are here, of course. The cute home movies. The excursions into dimly lit recording studios, boardrooms full of record execs emphatically head-nodding to the new record, and chaotic backstage war zones. It’s important that the pop star get a little pissed off sometimes so that she might politely but firmly reiterate her exacting vision to various wayward subordinates. Lady Gaga, for example, has what she calls “a little baby meltdown” in Five Foot Two on the set of American Horror Story. She is uncertain exactly how to handle her accent while delivering the line “The soldiers blamed me for their tumultuous journey,” and she informs her wishy-washy directors, not unreasonably, that “this is not the only thing I’m doing.” Beyoncé’s voice can take on a similarly sharp tone. “I have, like, a million notes,” she tells the crew staging an upcoming, cozier live show that looks to be going terribly wrong. Her first note: “The set looks really fake.”

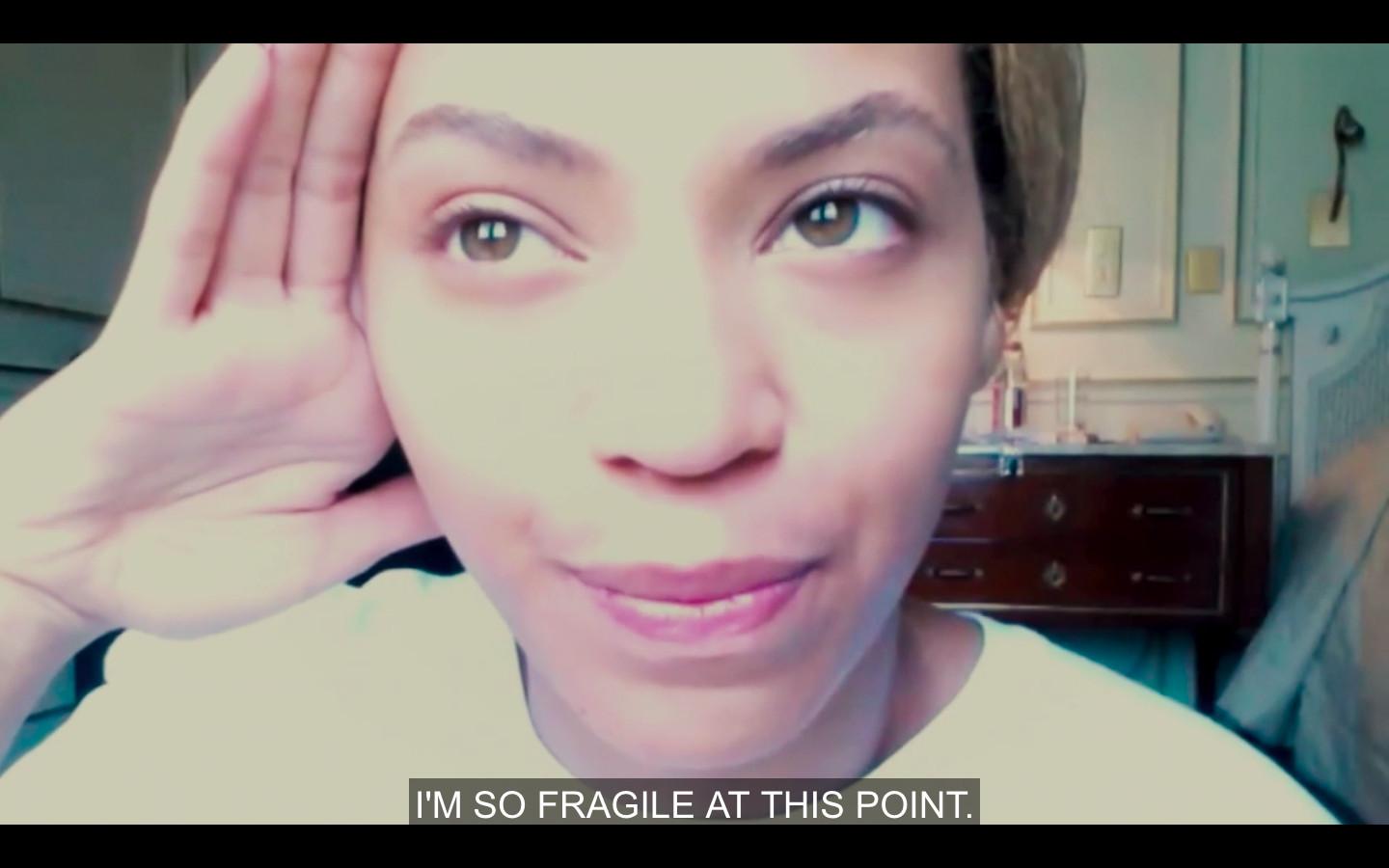

The problem is that the show in question is not really going terribly wrong: Beyoncé is too perfect, at least onstage, to ever let that happen. Life Is But a Dream at least toys with the idea of suspense. She plays up her decision to fire her manager—a.k.a her father, Mathew Knowles—as a cataclysmic event and insists that a splendid but fairly routine performance of “Run the World (Girls)” at the Billboard Music Awards constitutes “a huge artistic gamble.” A major conceit here is that Beyoncé apparently just loves to talk directly into her laptop during stressful or unguarded moments, but these, too, often feel like masterful performances disguised as lo-fi diary dumps. There are exceptions—when she gets pregnant with daughter Blue Ivy and feels the baby kick for the first time, her joy is infectious, her face ferociously radiant. But mostly, no matter how close to her laptop camera she gets, you’re somehow still held at several bodyguards’ arms’ length.

There is also plenty of utopian “on vacation with Jay-Z” footage, and yeah, wow, yikes. A movie about how she managed the surprise drop of her late-2013 album Beyoncé would be five times as interesting; a movie about the events leading up to the release of 2016’s Lemonade would be, oh, let’s say 200 times as interesting. Life Is But a Dream best serves its director’s agenda by ending before the real battle starts.

Not so with 2012’s Katy Perry: Part of Me, in which directors Dan Cutforth and Jane Lipsitz chronicle the blockbuster tour for her record-setting 2010 album Teenage Dream but also lean hard into the dissolution of her marriage to Russell Brand. Perry is, by leaps and bounds, the most convincingly regular, degular, shmegular girl in pop’s upper echelon, to quote someone who is definitely getting her own movie like this very soon. Even in full makeup and swathed in a massive softcore–Alice in Wonderland wardrobe, Perry is aggressively, winsomely human: Her voice is not exactly celestial, and the big screen (to say nothing of the 3-D) does her dancing no favors. But this only makes her will to power more impressive. You can’t help but like her, and not just because her team of managers and handlers keeps harping on how hard-working and likable she is. (You can take all these people at their word and still remember that they’re on the payroll.) Which in turn makes this late scene—and the best moment, by far, in any of these movies—all the more heartbreaking.

Perry starts every show by rising, via hydraulic lift, through the stage floor, microphone raised, the candy-cane pinwheels on her dress spinning, a wry smile plastered on her face. Some 200-plus days into the tour, however, when she is beyond exhausted and her marriage has collapsed entirely, she is sobbing in her dressing room before a show in São Paulo, Brazil, hardly able to rouse herself for the meet-and-greet. The managers and handlers look stricken; crew members on walkie-talkies brace for a last-second cancellation. But no, here she comes, her face still crumpling as she takes her position on the lift and raises her mic and the pinwheels start spinning, the smile only emerging at the last possible second. That’s show business. Reminder: Every moment in every movie like this, even if captured by accident, is painstakingly massaged and fully approved, and the more poignant the scene, the more likely it’s not quite on the level. But you come to appreciate the artifice in all this effort to convince you there’s no artifice at all.

Part of Me and Five Foot Two, despite the five-year span between them, are in intriguing feminist dialogue with one another, in that they both argue that professional success and artistic fulfillment on this scale will inevitably leave a female pop star’s personal life in shambles. Gaga reduces her plight to a brutal math equation regarding her past partners: “When I sold 10 million records, I lost Matt. I sell 30 million, I lose Luc. You know? I get the movie, I lose Taylor. It’s like a turnover.”

It will not surprise you to learn that Gaga has the deftest touch in this realm, effortlessly mingling high and low culture, impossible glamor and total exposure. She knows how to make her movie at least feel illicit, dancing in her Malibu kitchen and then giving the camera a coy don’t-film-this-OK-fine-film-this glance. Early on, she lounges on a sidewalk and reels off a sizable monologue about her love-hate relationship with one of her biggest pop star inspirations (“I just want Madonna to push me up against the wall and kiss me and tell me I’m a piece of shit”) and then tells the guy holding the camera, “You can use none of that footage.” Directed by Chris Moukarbel, Five Foot Two attempts a Katy Perry–style emotional climax, when Gaga receives flowers from her ex-fiancée on the day of her Super Bowl coronation. The various friends gathered in her Malibu mansion look on anxiously and brace for disaster. But she underplays the moment nicely—you respect her for respecting the viewer enough not to smash the vase against the wall.

Like Beyoncé, Demi Lovato spends part of her documentary fielding questions while lounging on a couch; unlike Beyoncé, the first thing out of her mouth is, “I actually had anxiety around this interview, because the last time I did an interview this long, I was on cocaine.” Directed by Hannah Lux Davis, Simply Complicated tracks Lovato’s meteoric rise from Disney princess to pop provocateur extolling the virtues of jujitsu and casual sex, and she, too, seems like a regular, degular, shmegular girl who just happens to have an antiaircraft-caliber voice. But the movie’s unblinking focus is on Lovato’s demons, from the early struggles that informed the song “Daddy Issues” to her substance abuse to her eating disorder. Her various managers and handlers insist that she’s super lovable but allow that in the throes of her addictions, she used to be horrible. Take those people at their word, too.

It’s quite the gut punch now when Lovato mentions that she’s been clean and sober for five and a half years, given that in June she released a song called “Sober” as a means of processing the fact that she’d broken her sobriety. Her jujitsu instructor chokes up on camera while expressing her desire to one day present Lovato with a black belt, and this is now officially the first time I have ever emotionally invested in someone’s journey in the martial arts. At their darkest, and/or at their best, these movies can make you genuinely care about someone you never cared about, or even like someone you used to enjoy performatively despising.

Which brings us to Ed Sheeran’s Songwriter, which despite the occasional burst of home-movie footage has few of the usual pop-doc trappings and tension-stoking indulgences. The director, Ed’s cousin Murray Cummings, is instead content to lurk in various corners while Sheeran finishes off his 2017 album, Divide, and cements his reputation as a flagrantly glamor-averse human. He’s not much for charisma unless delivering a line like, “I don’t like being around people,” and so instead he schlumps around random studios and writing camps, plying his craft in a way that makes you actually appreciate the craft.

Very little media of any sort has managed to capture exactly how modern pop music is written and recorded, with its interminable hours of hummed half-melodies and mumbled nonsense syllables. It’s a universe Bradley’s A Star Is Born doesn’t even pretend to respect or understand, but really, who understands other than the stars themselves? And so it’s bizarrely clarifying and uplifting to behold the god Ed Sheeran, swaddled in cargo shorts and a Hooters T-shirt, surrounded by ebullient Irish musicians and basically writing “Galway Girl” in real time. It’s not quite a “Shallow”-level revelation, no. But it increased my affection for Ed Sheeran by roughly 300 percent, an only slightly contrived slice of humble truth with the thrilling impact of pure, delusional fiction.