Is the Astros’ Trade for Justin Verlander the Best Deadline Deal in Baseball History?

Last year, he delivered World Series title to Houston just months after arriving from the Detroit Tigers in a shocking deal that required him to clear waivers. Now, with his team down 3-1, he’s about to take the ball in Game 5 of the ALCS and try to save its season.

Last Saturday night, as Astros right-hander Justin Verlander was cruising to a win in Game 1 of the ALCS in Boston, my colleague Robert Mays posed an interesting question:

This is subjective, because how you rank deadline trades depends not only on how you define the trade deadline but what you value: Is it all about in-season impact, or does a team get extra points for bagging a player who sticks around for years to come? If a team signs a free-agent-to-be who re-signs months after the trade, do you credit the trade for the added value in later years? How do you balance regular-season impact versus playoff impact?

All these moving parts make Mays’s question a great spark for bullshitting to pass the time while you’re watching the ALDS with friends, but it’s a little tricky to answer definitively.

Rick Sutcliffe won the NL Cy Young in 1984 after being traded from the Indians to the Cubs in mid-June, but Chicago lost the best-of-five NLCS in five games. CC Sabathia, an Indians ace who moved to the NL in a July trade, delivered one of the most dominant and iconic second halves in baseball history with the Brewers in 2008: 11-2, 1.65 ERA with seven complete games and three shutouts in 17 starts, the last three of them on short rest. Sabathia’s final start of the season was a complete-game 3-1 win over the Cubs to clinch the wild card in Game 162.

Sabathia, who played in Milwaukee for all of four months, still appears in Miller Park highlight montages to this day. But Sabathia lost his only playoff start, the Brewers were bounced from the NLDS in four games, and he signed with the Yankees that offseason. Even if June trades count as “deadline deals,” was the Sabathia deal the best deadline trade ever, particularly considering three-time All-Star Michael Brantley went the other way?

From a value standpoint, the best value in deadline deals probably comes from sellers: the Astros getting Jeff Bagwell from the Red Sox for Larry Andersen, the Braves getting John Smoltz from the Tigers for Doyle Alexander. But that doesn’t really fit the spirit of the question, which is more about contenders improving themselves in the short term.

Considering those trades, and what the Astros gave up, how Verlander performed, how long he’s under team control, and how the team’s postseason fortunes have shaken out, this has to be one of the best deadline trades of all time.

The best comparison for Verlander’s move to Houston is probably the July 2000 trade that sent Curt Schilling from the Phillies to the Diamondbacks. Schilling, like Verlander, was a veteran power right-hander who delivered ace-quality innings at as great a workload as any pitcher in the game. And like Verlander, Schilling was directly responsible for bringing a title to his new team: In 2001, Schilling finished second in the NL to teammate Randy Johnson in bWAR, ERA, strikeouts, and Cy Young voting. They were by far the two best pitchers in the NL that year: Johnson had 10.1 bWAR, Schilling 8.8, with third-place Javier Vázquez at 5.7; Johnson struck out 372 batters, Schilling 293, and third-place Chan Ho Park 218.

Perhaps more famously, Schilling made six starts that postseason, including three in the World Series, and he struck out 56 in 48 1/3 innings en route to winning a title and sharing World Series MVP honors with Johnson.

That’s the kind of impact Verlander had last year. He won all five of his regular-season starts with Houston, then won two more games in each of the first two playoff rounds, earning ALCS MVP honors by allowing one run and striking out 21 in 16 innings against the Yankees. In 2018, his first full year with the Astros, Verlander led the AL in strikeouts, WHIP, and K/BB ratio, while finishing second in innings pitched and third in ERA and bWAR.

If anything, the Verlander trade has worked out even better for the Astros than the Schilling trade did for the Diamondbacks. Verlander brought the team a title within two months of arriving in Houston, while Arizona had to wait a year after Schilling’s arrival for a title. And while the two best prospects in the Verlander trade—outfielder Daz Cameron and pitcher Franklin Perez—might turn into good players someday, both have a long developmental road ahead of them.

The Diamondbacks, however, traded away four big league contributors to get Schilling: first baseman Travis Lee and pitchers Omar Daal, Nelson Figueroa, and Vicente Padilla. The first three were substantial contributors to a 2001 Phillies team that improved by 21 games from the year before, while Padilla, the youngest player in the deal, went on to become an All-Star and throw more than 1,500 league-average innings in his career. All four players, in fact, had big league careers of at least nine years.

So considering the (probably) low price, Verlander’s multiyear commitment to Houston (he’s signed through 2019), and the fact that it resulted in a World Series the season of the trade, is at least one of the best deadline deals ever.

With Houston down 3-1 against Boston and Verlander set to take the ball in Game 5 of the 2018 NLCS and try to save their season, my question is: How the hell did this ever even happen?

Note the date on the trade: August 31. The non-waiver deadline is July 31, which means every team in baseball had the opportunity to just pluck Verlander and his contract off the Tigers’ roster and nobody bit.

Verlander burst onto the scene in 2006, when he was named AL Rookie of the Year and had the best ERA among starters on a Tigers team that went to the World Series, and ever since then Verlander’s been a constant in the AL Cy Young conversation. In 13 full seasons in the majors, he’s made 30 or more starts 12 times, thrown 200 or more innings 11 times, had an ERA+ of 120 or better 10 times, and struck out 200 or more batters eight times.

In 2011, Verlander posted a 172 ERA+ in 251 innings and won not only the Cy Young but the MVP award, and he probably should’ve won a second Cy Young in 2012, when he lost one of the closest races in history to future teammate David Price. Verlander has combined excellence with volume to an extent no contemporary pitcher apart from Clayton Kershaw can match, and he’s almost certainly going to end up in the Hall of Fame on the first ballot.

But there was a brief time when it looked like he was washed. In 2014, Verlander cratered. His ERA jumped by more than a run, from 3.46 to 4.54, and his strikeout rate dropped by two per nine innings. Verlander allowed more earned runs than anyone else in the American League, and out of 88 qualified starting pitchers, he finished 76th in ERA+ and 75th in wins above average. In 2015, Verlander started the season on the disabled list—the first such stint of his career—and failed to make 30 starts or qualify for the ERA title for the first time since 2005. But while Verlander’s K/9 rebounded to only 7.6 and his DRA (Baseball Prospectus’s ERA estimator) still rated him as below-average, Verlander’s ERA dropped back down to 3.38.

That two-season run was the first time Verlander had shown any signs of vulnerability since 2008, his third full season in the majors, and the timing was far from ideal. From 2006 to 2013, Verlander threw 1,760 2/3 innings in the majors, second-most behind Sabathia in that time, and 2014 and 2015 were Verlander’s age-31 and age-32 seasons. It seemed like a reasonable assumption at the time that Verlander was simply wearing down, like so many of his contemporaries. Félix Hernández was one of the best, most durable pitchers in baseball for a decade, then fell off a cliff after his age-30 season. At age 30, Kershaw is still one of the best pitchers out there, but he’s dealing with nagging back injuries and lost velocity far beyond anything he experienced in his mid-20s.

Worse, Verlander signed a 10-year, $219.5 million contract extension with the Tigers that kicked in before the 2010 season. Because the contract ate up some free-agency years, Verlander’s salary rose incrementally over time, from $6.75 million in 2010 to $12.75 million in 2011 to $20 million from 2012 to 2014. And in 2015, when Verlander was making his first trip to the DL and coming off the worst season of his career, his salary rose to $28 million.

It’s also important to remember that 2015 was the height of asset fetishization in baseball, the year the Cubs and Astros both emerged from tanking projects to return to the playoffs, the year the Cubs nakedly futzed with Kris Bryant’s service time to start the season. Between those two teams, and the Nationals and Giants rolling to October every year behind homegrown cores, it was becoming clear that young, cost-controlled players would be the championship centerpieces of the 2010s, just as high-priced veteran free agents had been in the 1990s.

So heading into 2016, Verlander turned 33, and, with two shaky seasons in his immediate past, his value was at its nadir. Then he went right back out and put it all back together. The injury that sent Verlander to the DL in 2015 was originally diagnosed as a triceps strain. After further investigation, the diagnosis was changed to a lat strain, then a bilateral sports hernia.

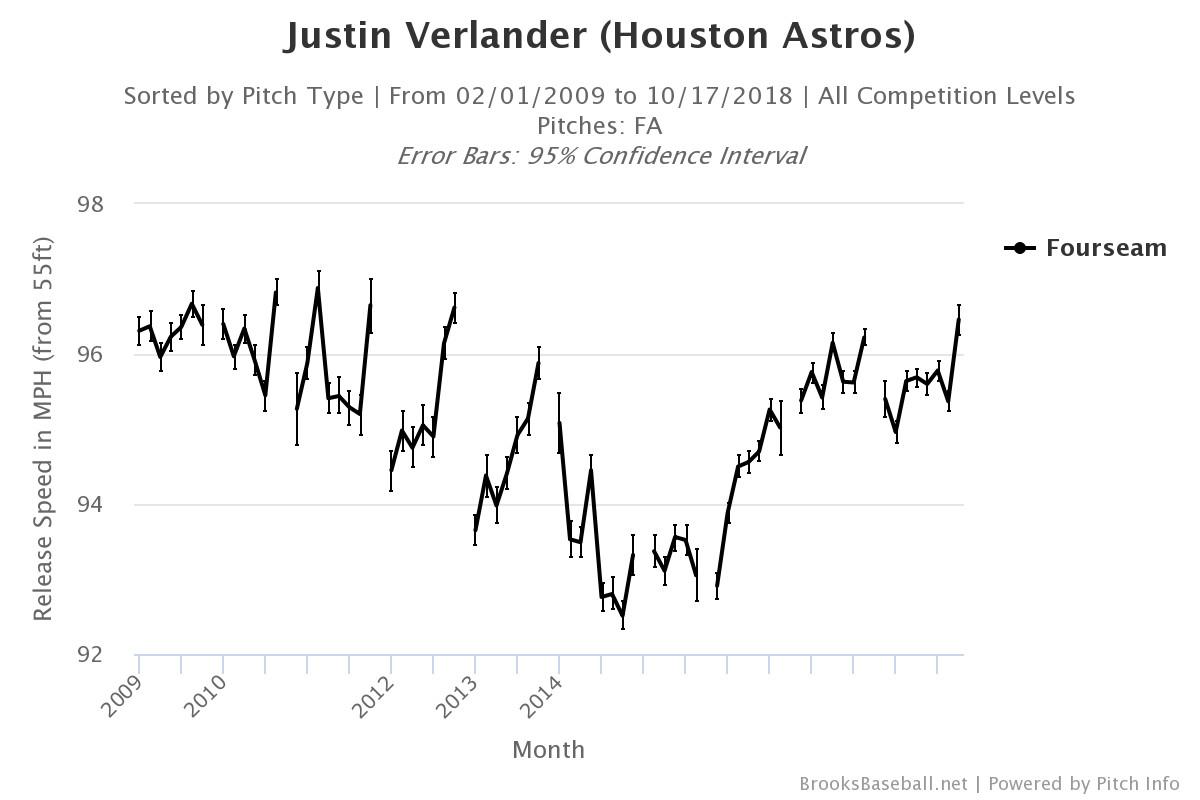

You’re not going to believe this, but a serious core muscle injury really does a number on a pitcher’s fastball velocity. Verlander’s fastball averaged 95 to 96 miles per hour through his late 20s, including his MVP campaign, then dropped to 92 to 93 in 2014 and 2015. Here’s a graph, courtesy of Brooks Baseball, showing Verlander’s average four-seamer velocity month by month since 2009. See if you can spot the period when he was pitching through a hernia.

By 2016, Verlander had finally been diagnosed correctly and healed. He made 34 starts, threw 227 2/3 innings, and once again led the AL in strikeouts. By pretty much any measure it was his best season since 2012, and just as in 2012 he finished a close second in Cy Young voting. The race in 2016 was a little weird, due to a lack of any real standout performances. Rick Porcello won, thanks to his 22 wins, despite Verlander earning 14 first-place votes to Porcello’s eight. By the time Verlander was traded in August 2017, he was pitching very well, if not quite up to his old standards: a 117 ERA+ in 172 innings over 28 starts while striking out a little better than a batter per inning. Taken in concert with his 2016 season, Verlander had been himself again for almost two full seasons.

Here’s where I get tripped up. If Verlander were obviously on the decline, or if the Tigers had decided to trade him in mid-2016, before he’d built up a track record of impressive post-hernia performance, I could see the two-plus years on his contract at $28 million a year being an obstacle. I could see not wanting to commit that amount of money to a pitcher on the decline, but by mid-2017, it was clear that Verlander’s rough two-year stretch was an injury-related dip, not a decline. By then everyone knew the cause of his struggles and had about 400 innings’ worth of evidence to support the idea that his injury was a thing of the past.

Here’s the thing about $20 million-a-year ballplayers: They’re not going to win you any awards for wringing every last cent of value out of a team. And sometimes, you guess wrong about how a player’s going to age, and you end up with Albert Pujols. But most of the time, players get paid this much because they’re … well, good. How much better off are the Red Sox for signing J.D. Martinez this past offseason, rather than giving in to concerns about his age and position? There’s something to be said for just paying sticker price for a good ballplayer.

The Astros, of course, didn’t even do that. They gave the Tigers less for Verlander than the Cubs did for José Quintana two months before, and perhaps about the same as the Dodgers gave the Rangers for three months of Yu Darvish, or the Yankees gave the A’s for Sonny Gray. Not only that, but they got the Tigers to retain some of Verlander’s salary, so they’re paying him only $20 million a year this year and next, and not $28 million. All because they pounced during a very specific time in baseball history, when the pendulum had swing too far in the direction of efficiency over quality, and before everyone seemed to realize that Verlander was himself again. Whatever happens in Game 5, history will remember this trade as a steal.