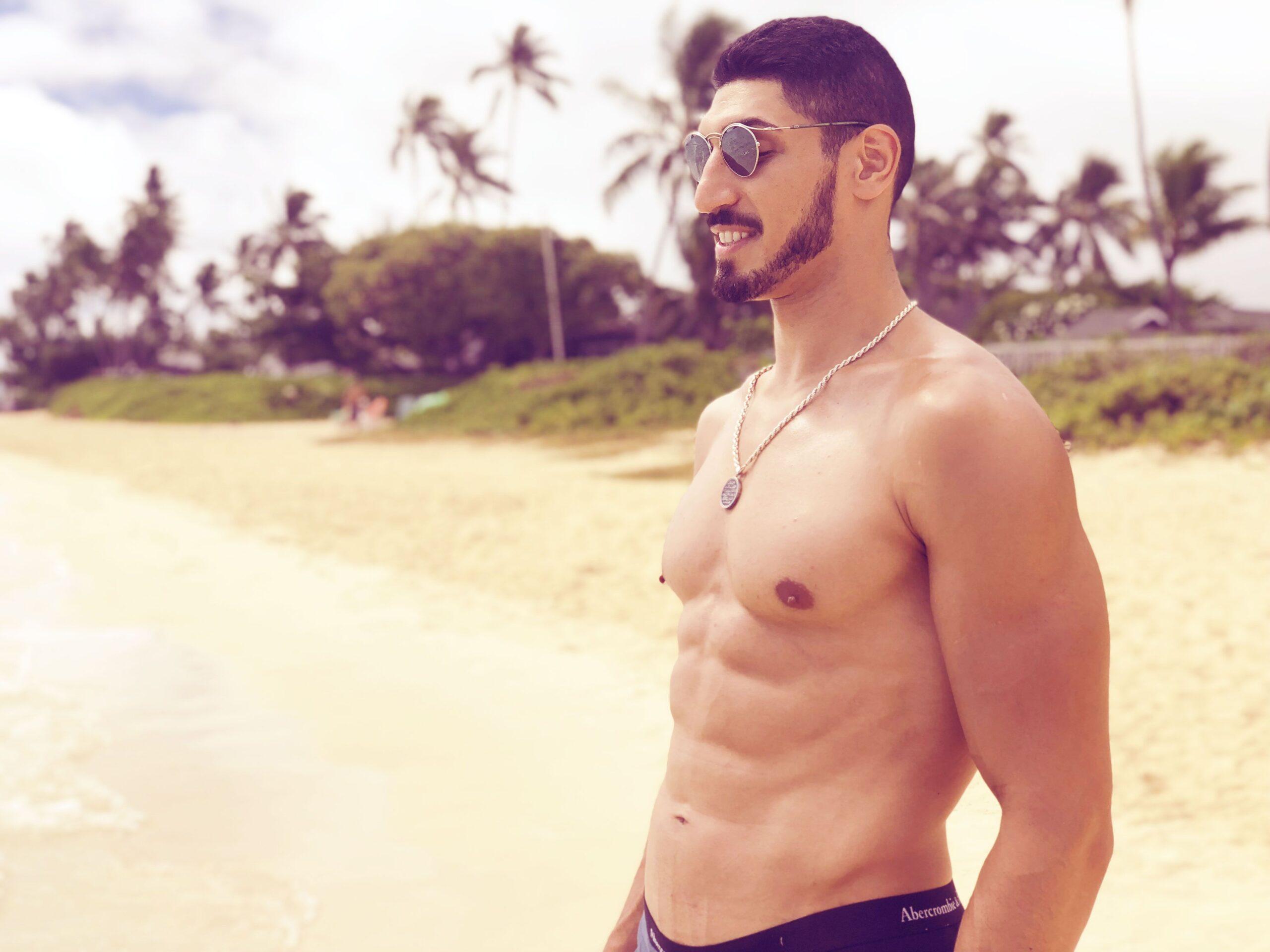

Enes Kanter is standing shirtless with his toes in the sand, surrounded by volcanic mountains and pristine sea as, just a few feet away, a small and swift bonnethead shark circles. Kanter is arguing, at the moment, about his muscles.

“Stop flexing,” says Hank Fetic, Kanter’s manager, phone lifted and camera app open. Kanter’s already-ample pectoral muscles swell. He cuts his eyes toward Fetic. “I don’t need to flex,” he says with a grin. “This is my normal.”

Fetic smiles, rolls his eyes, and starts shooting. Kanter needs a photo for Twitter. He needs it to be perfect. And he needs it right now. He needs it because we’re on Lanikai Beach of Oahu, one of the most gorgeous places on one of the most gorgeous islands on earth, and he needs it because he’s nearly back in preseason shape, which means his body is rippling with muscles in places where, for most humans, muscles will never, ever show.

“Regular mode or portrait?” Fetic asks.

Kanter looks borderline insulted. “Portrait,” he says. “Always portrait.”

A few minutes later he takes the phone from Fetic and prepares to send one of the pictures out into the world. Then he starts walking. We wander down Lanikai Beach’s half-mile stretch of sand, past a number of beachgoers who observe but do not approach the 6-foot-11 man in their midst.

Kanter is many things: New York Knicks center, devout Muslim, star of #NBATwitter, and enemy of the Turkish state. For the moment though, he is like anyone else on this beach—just another person in paradise, awed by all that surrounds him. “This is unbelievable,” he says.

As we walk, staring out at the Pacific in a place that feels something like the edge of the world, Kanter begins talking about other faraway places that he has considered home. At 26 years old, Kanter is no longer connected to his country or his parents, who still live there. His continued criticism of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has landed Kanter’s father in jail and made Kanter a target of harassment and social media threats on his life. “I don’t know if he’ll ever be able to go back to Turkey,” says Fetic. “Ever.” He is rootless, building makeshift communities everywhere his life and NBA career takes him.

He finds belonging in unlikely places. A living room in Pennsylvania. A locker room in Oklahoma. The entire state of Kentucky. All have served, at least temporarily, as a refuge, giving Kanter comfort for anywhere between a few hours and a few years before he inevitably goes searching, once again, for someplace else he might call home.

Right now, home is New York. Kanter got the call that he’d been traded in September of 2017 while standing in a gym, surrounded by kids at one of the basketball camps he hosts. “Don’t look too happy,” he remembers his other manager, Mevlut “Hilmi” Cinar, telling him. The camp, after all, was in Oklahoma City, home of Kanter’s then team. “You’re going to New York.” Kanter suppressed a smile, finished the camp, and packed his bags.

Kanter had been buried on the bench in Oklahoma City as an offensive specialist on a team full of defensive holes. Though he says he loved OKC, New York offered a chance to start and contribute in the biggest market in the league. “It’s New York,” Kanter says with the knowing shrug of one of the city’s natives. “You can’t beat it.” The Knicks were bad in his first season and will probably be bad in his second, but so far, Kanter has responded well to the move. He averaged 14 points and 11 rebounds on 59 percent shooting last year. He won the respect of teammates and fans after showing up for a December game against the Hawks on crutches due to a hip injury, then proceeded to score eight points in 18 minutes. “That guy is unbelievable,” said Knicks star forward Kristaps Porzingis. “He’s a warrior.” New coach David Fizdale has already been effusive in giving Kanter his praise. “I think he’s a top-five back-to-the-basket power player,” Fizdale said recently. “I just don’t see that anymore. Those are a dying breed and we actually have one.”

Later we’re sitting in a sushi shack on the edge of Honolulu, and Kanter is scrolling through Twitter, looking at his mentions. Replies are rolling in to the picture of himself shirtless on the beach, and, well, he’s kind of getting roasted.

Someone calls him ugly. (Fact check, based on the several women I watched vie for his attention over two days and based on my own inability to look away from the aforementioned muscles: false.) A few others insist that the photo has been edited. (True. “Just a second—I have to whiten my teeth,” he said before posting the image.) And one more calls Kanter a “real life Borat.” (False and racist.) He scrolls right past most of them, unbothered, just a little light trolling that comes with being a famous man who is Extremely Online. One reply, though, grabs Kanter’s attention.

“Why your nipples so hard? Excited to not make the playoffs?”

He reads it aloud and he laughs, and then Fetic laughs a little louder, and soon they’re going back and forth.

“Dude,” says Fetic, “you should say something like that.” In addition to being one of Kanter’s two managers, Fetic is also one of his closest friends. Born in Bosnia, Fetic moved to Canada as a refugee at age 6, so he understands Kanter’s rootlessness. An observant Muslim (though far less devout than Kanter), he also appreciates Kanter’s devotion to his own faith. As much as anything, though, he shares Kanter’s goofy sense of humor and delight in the NBA internet’s absurdities. So he eggs his client on.

“When I think about the playoffs,” Kanter says, barely audible through his own laughter, flipping the tweet a little bit, “my nipples get hard.”

“Yes!”

“Yes. That’s it.”

Weeks later he’ll be sitting at the podium in front of reporters at Knicks media day, and he’ll say exactly that. There will be laughs, and then tweets, and then blog posts aggregating the tweets, and soon enough the whole thing will go viral. Kanter ranks among the biggest stars in NBA Twitter, not only for his own tweets but also for his ability to speak and act in ways perfectly suited to the medium that drives so much consumption of today’s league. He talks shit to Kevin Durant. He gets in LeBron James’s face. He sometimes seems to exist as an on-court proxy for fans, acting out the feelings they can only scream from the keyboard or the stands. He is a meeting in Temecula, fully enfleshed.

A few days after media day, Kanter posts another tweet that garners relatively little attention. He posts a photo, showing him alongside his Knicks teammates, gathered together on a plane, with a single word that speaks to the way Kanter approaches both his basketball career and the wandering he does in his life away from the court: “Family.”

He has lived away from his actual family ever since he was 16. Basketball took him from Ankara to Istanbul, where he played for Fenerbahce in the EuroLeague, the second-best basketball league in the world. He moved from there to the United States at age 17, hoping to play a year at prep school before going to college. He spent time at Findlay Prep in Nevada and Mountain State Academy in West Virginia, but both decided not to let him play because, he says, he’d signed a shoe contract in Turkey. Oak Hill Academy coach Steve Smith, who runs perhaps the top high school basketball program in the country, said his team would not play against any school that accepted Kanter, because the center was already a professional. Schools found it not worth the hassle to keep him on their roster, even though he ranked among the top prospects in the country. “I knew nothing about the eligibility rules,” he says. “I thought it would be no problem for me to play.” He finally found a program willing to take him, Stoneridge Preparatory School in California, where he played a season before going to Kentucky with plans to spend a year playing for the Wildcats in Lexington.

He never got the chance. The general manager of Fenerbahce, Nedim Karakas, told The New York Times it had paid Kanter and his family more than $100,000 in salary and expenses, making him a professional. (Kanter said then and now that the figure was significantly lower.) The NCAA launched a probe into Kanter’s European career, and he sat through multiple hours-long interviews about how and when he’d been compensated for his labor. Before one of his interviews, Kanter says, “One of the lawyers told me to show up in Kentucky sweats instead of nice clothes so that I would look poor.” It didn’t work. The NCAA declared Kanter permanently ineligible. After the news broke, Kentucky head coach John Calipari called Kanter into his office. Kanter says Calipari had always known the facts of his shoe deal and his contract with Fenerbahce—“Calipari always knows everything,” he says—but had remained hopeful that Kanter would be eligible to play. Kanter was devastated, but he remembers Calipari immediately telling him, “You’re still a part of our family. If you want to stay here, you should stay. If you want to go back to Europe, then go ahead.”

I was really sad. I was lonely. I said to myself, ‘Maybe America doesn’t want me.’Enes Kanter

Kanter didn’t hesitate. “I’m staying,” he said. He couldn’t bear the thought of returning to Turkey before reaching his dream of playing in the NBA. Back home, coaches had told him that the best path to the league was to spend several years as a pro in Turkey instead of trying to navigate the American amateur system. “If I went back,” he says, “then everyone there would say I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t let that happen.” So instead he stayed in Lexington, where NCAA rules prohibited him from practicing with the team. “Sometimes,” he says, “I would be in the weight room with them, but they weren’t allowed to talk to me. But they had written instructions on how to do all of the exercises—how many sets, all of that—so I would just follow them around the room and do what was written on the paper.” He laughs, still disbelieving the absurdity of it all. “Man,” he says, “I hate the NCAA.”

It had been nearly two years since Kanter left Istanbul and the EuroLeague, and all he had to show was two semesters of college classes and a single season of mediocre prep school basketball. “I was really sad,” he says. “I was lonely. I said to myself, ‘Maybe America doesn’t want me.’”

The NBA still did. Utah took Kanter third overall in the 2011 draft. “I didn’t want to go to Utah,” he says. “They already had so many bigs.” For years, Kanter sat on the bench behind the likes of Paul Millsap and Al Jefferson, struggling to adapt to the NBA. He developed into a solid contributor in his third year and was traded to Oklahoma City in his fourth, where he began to blossom. After the trade, Kanter averaged 19 points and 11 rebounds on 57 percent shooting, beginning to live up to his massive potential. The Thunder rewarded him with a max contract. That season, he says, was the most fun he’s ever had playing basketball. He bought a house in Oklahoma. He built deeper relationships with teammates than he had anywhere else. He began to carve out a life for himself in this country, a locker room and fan favorite on one of the NBA’s best teams—someone OKC fans would give a standing ovation upon his return as a Knick. “He’s a great teammate and [a] competitive guy,” Thunder coach Billy Donovan later said of Kanter. “He really buys into his teammates. … I don’t know if Kanter was in a leadership role with us at the time, but he was a great connector.”

America did, in fact, want him. But by the time Kanter was traded last September from Oklahoma City to New York, Turkey no longer wanted him back.

While Kanter built his career in the NBA, he watched from afar as Turkey devolved from a relatively stable democracy into an increasingly authoritarian state. First came the Turkish government’s 2013 corruption scandal, in which dozens of members of Turkey’s elite, including some at the highest levels of government, were arrested for involvement in a money-laundering scheme intended to bypass American sanctions against Iran.

Then came the darkest night in Turkey’s recent history: July 15, 2016. That night began with two major bridges in Istanbul closing, as the Turkish army deployed tanks and troops in its own city’s streets. Soon fighter jets were spotted flying above Istanbul and Ankara, and Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim (elected after Erdogan became president) made an announcement: These were not sanctioned military activities. This was an attempted coup d’état.

An anonymous cabal from within the military issued a statement saying they were retaking the country, reinstating human rights and constitutional order. In the meantime, though, bombs dropped over the Parliament building in Ankara and explosions were reported throughout both the capital and Istanbul.

In the midst of the violence, Erdogan gave a FaceTime interview to CNN Türk in which an anchor held up her phone to the camera to show Erdogan, speaking before drab curtains in an undisclosed location, vowing that the efforts would not succeed. He encouraged Turks to take to the streets in resistance to their own army. He made vague references to the coup’s plotters taking direction from abroad. “Turkey,” he said, “will not be run from a house in Pennsylvania.”

All the while, Kanter was sitting in front of a television half a world away, watching, fully rapt, from a house in Pennsylvania.

The house belonged to Fethullah Gulen, a Muslim cleric and public intellectual who has long served as the leader of the “Hizmet” movement (Turkish for “service”), of which Kanter is one of the most famous members. Gulen is a mysterious, complicated figure. The New York Times has described his movement as a “moderate, pro-Western brand of Sunni Islam that appeals to many well-educated and professional Turks.”

Kanter grew up attending one of the Hizmet movement’s schools, of which there were once about 300 in Turkey and 1,000 worldwide. The schools are known for their academic rigor and emphasis on the sciences, reflecting Gulen’s core belief in the interreligious dialogue and the compatibility between religious and scientific truth. To ease his transition to the United States, Kanter connected with other Turkish nationals connected to the Hizmet movement, and soon he began making regular trips to Gulen’s home in Pennsylvania, a large and leafy compound often filled with staffers, friends, and volunteers. There, Gulen often gives private lectures to visitors on topics ranging from Islamic scripture to German philosophy to theoretical physics. “I love going there,” says Kanter. “He’s a brilliant, amazing man.” Adds Fetic: “I think as much as anything, Enes loves going there because he can find a level of comfort that’s hard to get anywhere else. People speak Turkish. They eat Turkish food. They talk about places and ideas that are familiar to him.”

Gulen has long been a controversial figure in Turkey. Despite his passion for promoting an Islam that is conversant and compatible with Western culture, many in Turkey have long been suspicious of his motives, seeing his influence as antithetical to the country’s tradition as a secularist state. Some call Hizmet a cult. “I would consider the Gulen movement a high-pressure religious group bordering on a cult-like organization,” says Aykan Erdemir, a former member of the Turkish parliament, where he represented the secularist Republican People’s Party, and currently a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. “Gulen-affiliated schools in Turkey have historically had a heavy emphasis on math, sciences, and English-language skills, alongside behind-the-scenes indoctrination into Gulen’s teachings. This came with the expectation that you would be loyal to the Gulen network for the rest of your life.”

Kanter seems unbothered when I mention the characterization of Hizmet as a cult, but also eager to push back. “I don’t really understand that,” he says. “I know this man, and the biggest thing he cares about is education. Not just religious education, but education—period. Why is that a bad thing? How is that a cult?” Kanter also points to the fact he’s known of people to leave the movement without facing any sense of retribution or animosity. Steven Cook, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who recently interviewed Kanter for Salon, says of Gulen: “He’s very good at presenting the face of this oppressed progressive religious group. And I believe those things are truly very important to the movement—Islamic principles, science, interreligious dialogue. But they’re also hardcore nationalists.”

Hundreds of people died, a lot of them in terrible, awful ways. Your family is still there. You don’t know what’s going to happen to them. You don’t know what’s going to happen next. It was the worst feeling in the world.Enes Kanter

For years, Gulen and Erdogan had been allies. While Erdogan wielded power in government, Gulen wielded influence over the attitudes and priorities of many members of Turkey’s middle and upper classes, each man seeming to work toward a Turkey that was devoutly Islamic but open to Western ideas and institutions. Their relationship began to fray early this decade. “A behind-the-scenes power struggle between former allies erupted into an all-out war in 2013,” says Erdemir. That year, officials widely believed to be part of the Hizmet movement led much of the investigation into corruption in Erdogan’s government. “It was a question of, ‘Now who’s going to be the big boss?’” Against the backdrop of this dynamic, Erdogan took little time to assign blame on the night of the coup attempt. This, he believed, was Gulen’s fault.

Gulen has denied any involvement. “If there was one little piece of evidence that the Gulen movement was involved,” Kanter says, “the United States would deport him.” No public evidence has emerged to link Gulen to the effort. Kanter was with Gulen—whose home he visits often—on the day of the coup attempt, he says. “I was with him,” Kanter says of the man accused by Erdogan of masterminding the entire operation. “I was with him the whole time, and do you know what he was doing? He was sitting there watching on television and praying for his country. That’s it.” Kanter says that everyone in the room was horrified by what they saw. Even among a crowd of people who vehemently opposed Erdogan’s rule, no one wanted to see him removed from power like this. “It was a nightmare,” Kanter says. “Even if there was a chance Erdogan might go down, you never want to see that happen to your country or your people. Hundreds of people died, a lot of them in terrible, awful ways. Your family is still there. You don’t know what’s going to happen to them. You don’t know what’s going to happen next. It was the worst feeling in the world.”

The coup attempt failed. Erdogan’s message to supporters to take to the streets worked—thousands flooded the country’s major cities, and their resistance was enough to slow the military segment’s rogue efforts. Military factions loyal to Erdogan overtook those who’d initiated the coup, and by a little after midnight in Istanbul, soldiers had surrendered to police units loyal to the government, and the country’s interior minister announced that the effort had been “neutralized.”

Newly emboldened, Erdogan cracked down on his enemies harder than ever in the days and months that followed. All Hizmet schools across the country were shut down. Many thousands of government employees—from police to bureaucrats to academics—were fired from their jobs, according to TurkeyPurge.com, a site run by Turkish journalists. More than 80,000 people, many with Gulenist sympathies, have been arrested, according to both the same site and to Cook. “These people are essentially political prisoners,” says Cook. “The evidence against them is extremely thin.” Once seen as a democratic reformer, Erdogan is now regarded by many in diplomatic and human rights circles as, essentially, a dictator-lite. “He’s a ruthless authoritarian,” says Cook, who also acknowledges that Erdogan is a masterful politician who enjoys wide support, even as he terrorizes the many Gulenists and secularists who oppose him. “What you have,” says Cook, “is this modern-day reign of terror—without the blood.” While Erdogan has accused Gulen of masterminding the coup attempt, Kanter and others have suggested that Erdogan planned it himself. Says Cook: “I don’t think we’ll ever know what really happened. But I think what happened is somewhat less important than the political effects of the event. Not to suggest that I think it was put on by the government, but what I do know is that the coup attempt has benefited Erdogan greatly to accelerate a purge that was already underway.”

TurkeyPurge reports that 189 media outlets have been shut down and 319 journalists arrested. With the media now almost entirely under government control, Erdogan ramped up his anti-Gulen rhetoric, and anti-Hizmet sentiment spread further than ever before. “The secular crowd has been skeptical of Gulen since the very beginning,” says Erdemir. “Now you have the pro-Erdogan crowd denouncing Gulen even more loudly. He has come to alienate the entire political spectrum in Turkey.”

Kanter’s support never wavered, and in fact, only grew more public. After the Turkish government declared Hizmet a terrorist group, it reportedly issued a warrant for Kanter’s arrest, along with many other members of the group. He responded to an article about the warrant from pro-Erdogan newspaper Daily Sabah, writing on Twitter, “You can’t catch me. Don’t waste your breath. I will come on my own will anyway, to spit on your ugly, hateful faces.” Within three weeks of the coup attempt, his father issued a statement disowning him. “With a feeling of shame, I apologize to our president and the Turkish people for having such a son.” People close to Kanter suspect that his father’s statement came from a mix of genuine frustration and government pressure. Kanter hasn’t spoken with his parents since. He suspects that their phones are tapped, and that they’ll risk imprisonment or worse if they communicate with him in any way. “Enes is an incredibly brave young man,” says Y. Alp Aslandogan, executive director of the Hizmet movement’s Alliance for Shared Values and Gulen’s adviser and spokesman. “He could have sat under the radar and just played basketball and refused to say anything about human rights abuses under President Erdogan. He chose to speak up. His conscience won’t let him stay silent.”

Last summer, Kanter left for an international tour, conducting basketball camps and volunteering for charities across the world. The previous summer, Kanter had visited several countries across Africa, and this time, he wanted to visit others across Asia and Eastern Europe. Alongside his friend and other manager Hilmi Cinar, Kanter conducted camps in Hong Kong and Japan, typically staying overnight in the schools, all without incident. Next, he flew south to Indonesia.

“I was a little nervous about Indonesia,” says Cinar, a fellow Turkish national who has known Enes since he first moved to the United States. The country’s Islamist government has built a strong alliance with Turkey and Erdogan, who has shown a willingness to target enemies of the state on foreign soil. Cinar had local police support throughout their time in the country, and they decided to stay in a hotel rather than at the school. At 1:30 a.m., Cinar’s cellphone rang. It was his local fixer.

Cinar remembers him saying that a couple of men, claiming to work for the federal government, had come by the school and asked about Kanter, wondering if he was staying overnight at the school. It probably wasn’t a big deal, Cinar remembers his fixer saying. He just thought Cinar should know.

Cinar bolted out of bed. He banged on Kanter’s door. “We have to leave the country,” he said. “Now.”

Kanter was unmoved. “Let’s stay!” he said. “It’ll be fine. Let’s get some sleep.”

Cinar insisted. He looked online for the next available flight out of the country—he didn’t care where. He saw one at 5:30 a.m. headed for Singapore and booked two tickets. They rode to the airport, made it through security, and Cinar relaxed the moment the plane left the ground. He never heard exactly why the men had come looking for Kanter but felt confident they’d done the right thing by rushing away. Soon enough he and Kanter were in the air once again, flying from Singapore to Germany, where they would connect to Romania, another close ally of the Turkish government, where Kanter was scheduled to work another basketball camp.

Romanian immigration and customs officials wouldn’t let Kanter in the country. For hours, he sat in the airport, unsure of what might happen next. Cinar says officials told them that they’d received a letter from the Turkish government saying that Kanter’s passport had been revoked. “It was the craziest day,” Kanter says. “But right away, I knew exactly why this was happening.”

Erdogan. Kanter took out his phone and recorded and tweeted a video of himself in detention, in which he said, as he often has, that the Turkish president was “the Hitler of our century.” (Cook throws some cold water on this comparison. “You can understand the anger and the depths of the despair,” he says. “But I think there’s a certain category that’s maybe Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, and no one else. The Hitler thing is way over the top.”) While Kanter was detained, Cinar called the NBA, the National Basketball Players Association, and a team of lawyers in the United States. Cinar was afraid that the Romanians would send Kanter to Turkey. “If I went back there,” Kanter says, “you might not hear from me again.”

He could have sat under the radar and just played basketball and refused to say anything. ... He chose to speak up. His conscience won’t let him stay silent.Y. Alp Aslandogan

Finally, the Romanian officials had enough. “We tried to play it tough with the Romanian police,” says Cinar. “We were saying, ‘This is unlawful. You can’t do this. We’re going to court.’ Finally, they said, ‘We don’t care about what’s going on between you and the Turkish government. Just get out of our country.’” They booked a flight to London, where they stayed in an airport hotel before flying back to the States. Kanter had no problem clearing customs on American soil. He scheduled a press conference and went on CBS This Morning to tell the story of his experience. Just over a week later, his father, Mehmet, whom Kanter still hadn’t spoke to since he’d been disowned, was arrested.

“They thought they would shut me up,” he says. “But no. Because this is what they do. This is who they are. I’m famous, and they’re doing this to me and my family, but they’re doing so much worse to so many more people who don’t have the platform that I have. So I can’t shut up. It’s my responsibility.” Days after his arrest, Mehmet Kanter was released. In June, he was charged by a Turkish court for being a “member of a terrorist organization.”

As Turkish public opinion has turned against Gulen, so it has against Kanter, perhaps Gulen’s most famous acolyte. Soon after the coup attempt, Kanter began receiving death threats, primarily on social media. “Every time I go out,” Kanter says, “I make sure I have someone with me. Or if I’m alone, I make sure I’m talking to someone on the phone. You never know. It only takes one crazy person.” He now avoids Turkish restaurants or sends friends to pick up orders to go because he never knows whether he’ll be met with warmth or venom. He has fallen out with other Turkish basketball players, including NBA veteran Hedo Turkoglu—who has served as an adviser to Erdogan and has called Kanter a “traitor,” saying, “I hope God never gives anyone a son like him”—and former Jazz teammate Mehmet Okur. “I still text him,” Kanter says of Okur. “Text, Instagram, Twitter—he doesn’t respond at all. I was cool with him. I was cool with all those guys. And I still respect them. But now they’re scared to text me.”

There are still only a few places in America where he can find well-seasoned köfte or a proper baklava, where he can hear his native language and find himself pulled back into the sensory experience of a life he long ago left behind. Gulen’s house is one of them. Cinar’s is another. Mostly, though, Kanter finds himself in search of new experiences in new settings, basketball serving as his portal to other worlds.

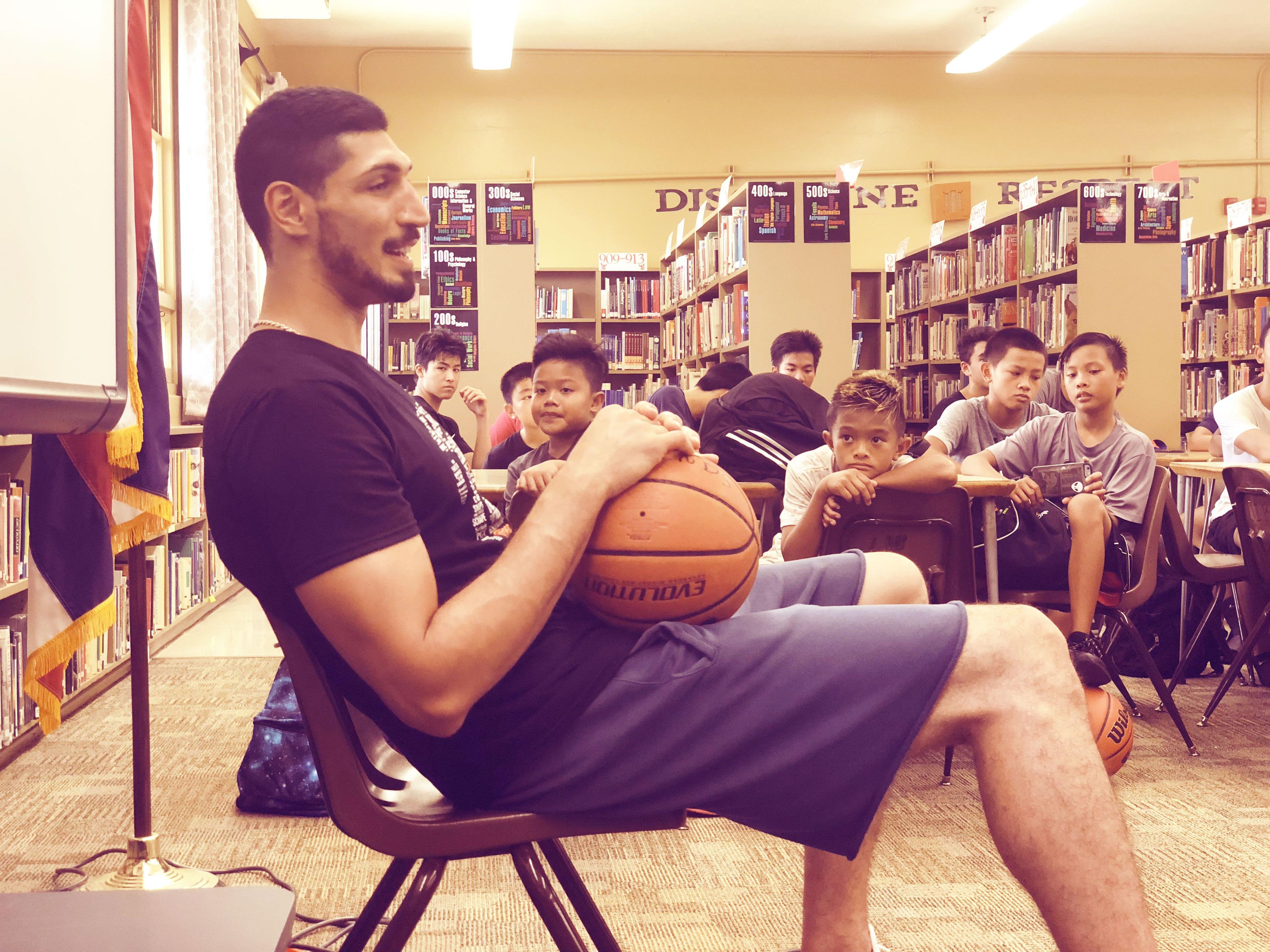

He’s in a new place now, on his first trip to Hawaii. And now, after a morning riding around Oahu and walking along the beach, he’s found himself sitting at the front of a library, surrounded by a few dozen children, many with hands raised. He’s at a high school on the outskirts of Honolulu, working at a basketball camp, where he’s just spent the past hour floating around the gym and helping kids with drills. Now, it’s time for a question-and-answer session.

What’s your diet?

“Very strict,” he says. “I don’t eat a lot of carbs, and I don’t eat much meat.” (Though fish is an exception.)

Who’s the GOAT?

“I would say Michael Jordan. I think if you ask around the league, 95 percent of players would say the same thing.”

Who’s been your best teammate?

“Oof,” he says. “You have to love all your teammates, but if I had to pick one, I would pick two. Russell Westbrook and Steven Adams.” (These two, he later tells me, both immediately texted him when they heard he’d been detained in Romania. “I’ll always be grateful to them for that,” he says.)

Are you still close with Kevin Durant?

Kanter smiles, a little deviously, and all around the room the children laugh.

“Next question, please,” he says.

Kanter’s history with Durant seems to follow him wherever he goes. They were, of course, teammates in Oklahoma City, part of a team that went up 3-1 on Golden State in the Western Conference finals before eventually falling in seven games. Durant left in free agency that offseason, joining the team that had defeated his own. And, well, Kanter and the Thunder were displeased.

Earlier this summer, Kanter posted a video of himself telling a kid to burn his Durant T-shirt. Durant fired back on an Instagram post of the video, writing “Gomd.” While remembering the whole thing that afternoon, after leaving the camp, Kanter asks me, with a big smile on his face, “Do you know what that stands for?” (It stands for “Get off my dick.”) Kanter laughs, clearly not offended, finding the entire back-and-forth appropriately entertaining.

Another evening, he looks through several pairs of sneakers at an event in a Christian Louboutin store on Waikiki Beach. Most of the shoes are a little too expensive, a little too flashy, for Kanter’s typical style, but he’s trying to branch out. At one point, Fetic says he likes a pair in blue and gold. “Are you crazy?” Kanter says. “Those are Golden State colors.”

Later, there is a moment, sitting at a sushi restaurant just a couple hours before Kanter’s flight, when he and Fetic reminisce about one of Kanter’s greatest social media hits, posted to Twitter just after DeMarcus Cousins signed with the Warriors:

“I was gonna tweet one more thing,” Kanter says, chopsticks in hand, smile spreading across his face. He looks at Fetic. “Should we tell him?”

“If you want,” Fetic says.

“Let’s tell him.”

Now Fetic goes searching through a notes app on his phone, searching for a draft of the tweet Kanter nearly posted. “OK,” he says. “Here it is.” Across the table, Kanter takes a bite of sushi and his smile grows. Fetic reads the proposed tweet: “Breaking News: My sources tell me that next year all Warriors games will be televised on Animal Planet, due to the amount of snakes on the team.” Now Kanter is cracking up. “We had to save that one,” he says.

“So,” I say, after a few moments of laughter. “I feel like I still don’t know the answer to this: Do you like KD?”

“I really like KD!” he says. “I really, really do. I actually think he’s a very nice guy, a very cool guy.”

When Oklahoma City first faced Durant after signing with Golden State, Kanter could be seen jawing at him from the bench. “That game—man, that game,” Kanter says. “That game was crazy. I have never experienced anything like it. I mean, I played in the Western Conference finals against that team. Seven games. And I promise you, it was never like it was that night.”

The memory of the months immediately before and after Durant’s departure from Oklahoma City still hurts. At the camp, one of the children asks Kanter for the best moment of his career. “My best memory is when we were up 3-1 in the playoffs against Golden State,” he says. “I don’t remember what happened after that, but that was my best memory.”

After some laughter, he continues, acknowledging that he does, in fact, remember. “You know, we kind of relaxed. We thought, ‘We’ve got it. We’re going to the Finals. If we get one more game, and then we can beat Cleveland.’ But they came back, and it was just so heartbreaking. I remember almost everybody in that locker room was crying. It was tough.”

They are, he insists, more than teammates. “I really do see them like brothers,” he says, riding to the Honolulu airport a couple hours after the camp. “Every team I play for, that’s how I feel.” I share something I’ve been thinking: That the personal stakes are a little higher for him than for most, that while some players can think of basketball as a business, even as their professional passion, he finds himself looking for something even more.

“It seems like everywhere you go, you’re working so hard to connect with the players, the city, the fans. It’s like you’re trying to make everywhere you go feel like— ”

He interjects. “Home.”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah.”

He’s quiet for a minute. Fetic is driving a Mustang convertible through the hills outside downtown Honolulu. “Everywhere I go,” he says, “I’m cool with everybody. I mean everybody. Teammates, coaches, the organization, the media, the fans. Because to me it’s not just basketball. To me, that’s my family.”

“But in some ways it’s not,” I say. “Because the business side gets in the middle of it.”

“Yeah,” he says. “They trade you, and it’s like, ‘OK, bye family. I guess I’ll go start again.’”

I ask if it would be nice to have one place where he could relax, with a community he knows is stable, with a sense that he belongs to a family that he knows will last.

“I don’t think that’s gonna happen, man,” he says. “Even if I stay with one team for four or five years, everything ends eventually.”

I ask whether he thinks most players in the NBA see their teammates as family like he does.

“No. Some do. But not most.”

To me it’s not just basketball. To me, that’s my family.Enes Kanter

I ask whether he thinks he’ll ever see his parents again.

“I think I will,” he says, voice soft. “I don’t know when, but I think I will. Maybe in Turkey. Maybe in America. I have no idea. But I think I will.”

He goes quiet. As the car rolls toward the airport, wind whips past us and Kanter sticks his right arm in the air. He’s headed back to New York to see friends he’ll soon call his family, and then he’ll start training camp with the Knicks and he’ll call those teammates his family too. Sometime soon there may be a trip to Chicago to see Fetic and Cinar, both of whom are like his brothers, and perhaps a visit to Gulen’s compound in Pennsylvania, where Kanter can still capture a sense of life in the country he left so long ago.

No, he doesn’t know when he’ll see his family or return to his homeland, but as he leaves America’s paradise for its most electric city, traveling both to and away from people he loves, he seems momentarily unbothered by the tortuous path that has brought him to this place in his life. “Basketball,” he told me earlier in the day, “makes all of the stress disappear.” The air is warm but the breeze is cool, and he lets his arm sway back and forth above his head for a few seconds until we reach the airport and he goes inside to fly away.