The Art of the Sidle: The Slickest Move in NBA Media

Sidling has become the great skill of the NBA beat, as fundamental to reporting as the corner 3 is to the sport itself. But not everybody can get a star player to talk when they want. Here’s how the best do it.Last week, Yahoo reporter Chris Haynes walked into the Lakers locker room and spotted LeBron James sitting alone. “LeBron is a different cat …” Haynes said later. “He’s got his headphones on. He’s playing music. He comes off like he doesn’t want to be bothered.”

“Man, I don’t care about that shit,” Haynes continued. “I walk over there. He takes his headphones off. We start chopping it up, talking in front of everybody.”

Any reporter who has been in an NBA locker room has seen this kind of flex. A writer snags a private interview with a superstar while envious reporters look on. Until now, the move didn’t have a widely agreed-upon name. It has been called the “side interview” and the “sidebar” and, when employed as the player leaves the court, the “tunnel walk.” But I prefer the term ESPN’s Brian Windhorst uses: sidling. As in, you sidle up to the players.

“If there’s something I don’t want everybody else to eat off of—if I’ve got a set of questions I know is going to elicit a pretty damn good response—I’m going to wait to get the players to the side,” Haynes said.

Every superstar player has a few [reporters] they’ll give time to. That’s because you have a relationship with them, and they know the reporters are not there trying to get clickbait or start something.Chris Haynes

“Not everybody can get ’em. That’s just simply what it is. Every superstar player has a few [reporters] they’ll give time to. That’s because you have a relationship with them, and they know the reporters are not there trying to get clickbait or start something.”

Sidling has become the great skill on the NBA beat, as fundamental to reporting as the corner 3 is to the sport itself. If you made a list of the NBA’s best sidlers, the list would be virtually identical to the list of the league’s most famous reporters. Haynes sidles. Ramona Shelburne sidles. Marc J. Spears sidles. Adrian Wojnarowski and Sam Amick and Howard Beck sidle.

Does Zach Lowe sidle? I asked one NBA writer.

“Everybody sidles,” the writer said.

Talking about “casual conversations” and “one-on-ones” can make NBA reporters sound like Bachelorette contestants. But for many writers, scoring the private conversation is as much a part of their identity as dashing off a snappy lede. “I don’t want the stuff that everybody gets,” said Athletic columnist Marcus Thompson II. “If I don’t get the side stuff, I don’t have a story yet.”

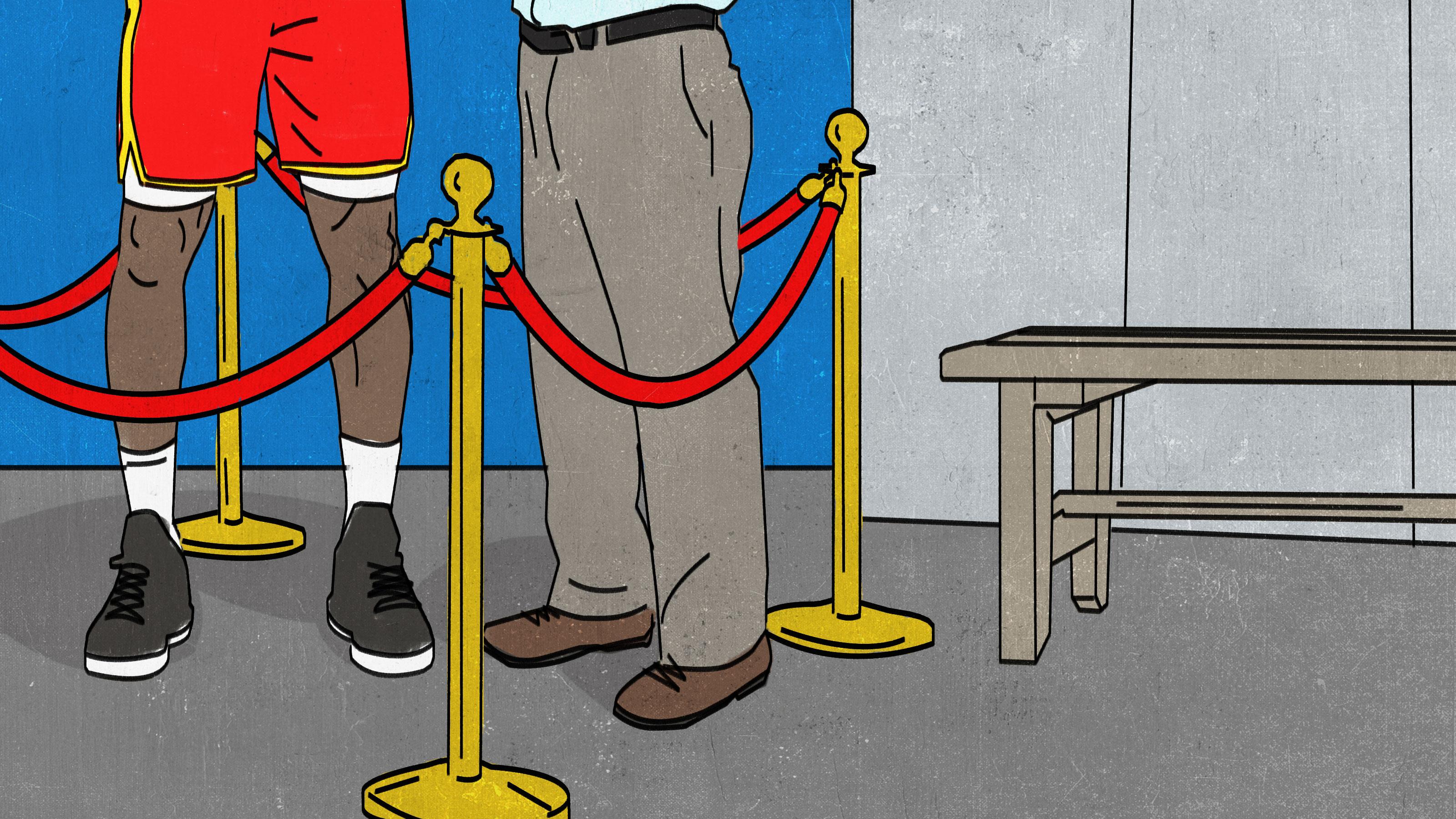

Sidling is also how NBA writers measure each other’s power. “You know when you get to the airport gate and you see the premium people line up and you’re jealous of that?” said Bleacher Report’s Tom Haberstroh. “That’s how you feel with Howard Beck and Stephen A. Smith and Brian Windhorst. Man, I wish I could get to that status—premium first class.” Getting there, writers like Haynes will tell you, requires a certain touch. For if sidling is a status in the NBA, it is also an art form.

In pro basketball, sidling is relatively new. “The concept you describe is completely a modern phenomenon,” said Bob Ryan, who started covering the league in the ’60s. “It didn’t exist in ‘my day.’”

Sidling became a rite of NBA reporting around the time of the Lakers’ back-to-back titles in 2009 and 2010. The sports media was ripe for it. Wojnarowski had come to Yahoo determined to replicate the reporting-based columns he’d admired in New York newspapers. “In my mind, if someone was flying me around and I’m traveling and they’re paying me, I got to get something nobody else has,” he said. “That was the pressure I always felt.”

At the same time, Kobe Bryant had become such a polarizing figure that his name could land a story on the Yahoo homepage. So after Lakers games, Wojnarowski and Bryant would walk from the locker room to the loading dock at Staples Center. There, Bryant would hold forth on everything from what critics were saying about him to the motivation of teammates like Pau Gasol. Before Bryant was on social media, Wojnarowski was delivering his in-the-moment spiel to the masses. As Wojnarowski told me: “I remember in my mind going, I hope he never gets on Twitter.”

To the untrained eye, sidling looks deceptively simple. As a player sets out for the team parking lot (at home games) or the bus (on the road), a reporter pulls alongside him like a car merging onto the freeway.

But the ability to approach a superstar is usually built on a relationship developed over a period of years. When Thompson sidles with Steph Curry, few people know that the two of them spent much of Curry’s early seasons in the NBA arguing about whether Denzel Washington’s character in the movie The Book of Eli was really blind. (Curry said he was; Thompson insisted he was not.)

To sidle, NBA reporters become geographers, learning the route a player takes to his car. They learn whether players shower before or after their postgame media scrum, whether they soak their feet after a game. In 2013, ESPN’s J.A. Adande was at a vending machine near the players’ parking lot at Staples Center when he saw Bryant fuming after a game. Adande knew that no matter what Bryant said publicly, he wasn’t getting along with Dwight Howard.

Though both reporter and player are hip to the ritual, sidling maintains the air of a chance encounter. Why Karl-Anthony, I had no idea you’d be in the bowels of the stadium right after a game!

“You don’t want to look like you’re standing there planted and waiting,” said Bleacher Report’s Jonathan Abrams. “At least, I don’t.” When he wants to sidle with a player who’s about to leave a locker room, Abrams will strike up a second conversation that can be ended quickly when his quarry makes for the door.

The standard question that opens a sidle is: “Got a minute?” Once, Bryant turned to Adande and said, “No, I don’t have a minute, J.A.”—a line that Tony Kornheiser and Michael Wilbon (mis)quoted on TV for years.

If the player does have a minute, what he tells a reporter falls into the gray zone between on and off the record. “Typically, the default is off the record,” said Windhorst. “But you may ask a player, ‘Can I use that?’” Thompson said players rarely demarcate what is and isn’t on the record, and a reporter’s ability to anticipate a player’s desires is part of what entitles him to sidle in the first place.

“I haven’t found a situation where it’s worth it to write it,” Thompson said of the forbidden, “off the record” stuff. “Once you write it, you better get a Pulitzer, because that’s all you’re getting.”

At its most basic level, a sidle is a player’s safe space. Last season, The Athletic’s Jason Quick noticed that Damian Lillard was putting his arm around center Jusuf Nurkic during timeouts and dead balls. “I waited until everyone left after a game and I asked him about it,” Quick said. “That’s when he revealed, ‘Yeah, I’m doing what I was wish LaMarcus Aldridge had done with me.’ Which was gold.”

Lillard probably wouldn’t have revealed his motives to a bunch of reporters in a scrum, but he trusted Quick to write the piece.

Quick’s was an ideal sidle, because he used it to work a specific angle or check out a bit of gossip. Experienced sidlers roll their eyes when they see reporters repeat fluffy questions they could just as easily ask in a press conference. “I feel if you’re getting a player in a one-on-one, a star player, I should be reading your story the next day,” Haynes said.

Sometimes there’s a little Trojan Horse action. ‘Yeah, I’d like to talk to you about your charity event and donating all that money.’ You drop in three questions about that and then say, ‘Hey, I hear you’re beefing with Paul George.’Tom Haberstroh

“I don’t think I do this,” Haberstroh told me, “but sometimes there’s a little Trojan Horse action. ‘Yeah, I’d like to talk to you about your charity event and donating all that money.’ You drop in three questions about that and then say, ‘Hey, I hear you’re beefing with Paul George.’”

Local NBA writers tend to look at national insiders with suspicion. Sidling makes this even worse. Almost nothing annoys beat reporters more, as they rush to fill a hole in the print newspaper, than seeing an insider with a far-off deadline moseying out of the locker room with a player. The beat writer thinks, Christ, what are they getting that I don’t have?

But occasionally, sidling serves everyone’s interests. When he was playing for New Orleans, Boogie Cousins gave multiple interviews to The Undefeated’s Marc Spears. Scott Kushner, who covers the Pelicans for the Baton Rouge, Louisiana–based Advocate, said the Cousins material was invaluable. “He said stuff he would not have said in a group setting,” Kushner said, “and would not have said to me, and I understood him better because he went to Spears.”

Sidling doesn’t have a formal code of ethics. The only real rule is that once a player and reporter are engaged, no one should crash the conversation. “It would be in incredibly poor taste,” said Quick. “Which isn’t to say it doesn’t happen.”

A national NBA writer told me: “It’s really annoying when you have a sidle—and it’s absolutely your sidle—and some local reporter comes in like that.” The writer pretended to thrust a microphone in my face.

Wincing in annoyance, the writer added: “You should respect the sidle as if it was your own.”

Got a minute to hear why NBA reporters sidle? One reason is that reporters don’t like revealing their hole cards. “In Portland media scrums, only one or two of us ask questions,” said Quick. “After a while, you get sick of feeding everyone information.”

Social media has made this problem worse. In the innocent, pre-digital age, a visiting national writer could wait for the beat writers to do their daily chores and then ask a player a question clearly intended for a feature. Say, Giannis, how much sleep do you get on the road versus at home?

Unless the player’s answer was really newsworthy, the beats would ignore it. But then writers like The Athletic’s Anthony Slater pioneered the video scrum. National writers began to fear their story ideas would be broadcast to the world. Short of an arranged one-on-one, sidling is the only alternative.

Sidling can be a safeguard against printing bogus information. In a 2002 playoff series against the Spurs, Shaquille O’Neal cut his finger and left a game to get stitches. Afterward, O’Neal told reporters that his dad had called him in the training room and ordered him back out onto the court. Adande thought the tale was suspicious and confronted O’Neal in the hallway. O’Neal smiled and said, “Marketing, baby.” Adande wrote that story instead.

If sidling is about reporting, it’s also about power. Wojnarowski’s walk-outs with Kobe tracked with his growth into the dominant NBA insider. Occasionally, reporters will flaunt a sidle in their copy. ESPN articles from a game site sometimes include the telltale phrase “told ESPN.com”—which roughly translates to, “told me while the rest of you suckers watched.”

The NBA postseason is a mass sidle-off. After a Finals game, a half-dozen or more writers will fake-casually stake out the same players—a scene Adande compared to “jockeying sailboats at the start of a regatta.”

“In big games people are paying attention to, it’s almost cringeworthy knowing I have a quote that’s in every other story,” said Thompson. To get something fresh, Thompson executes a pre-sidle. He grabs Curry or Kevin Durant after a game but before they walk into the media room to address the masses. When reporters are waiting for a Warriors player to show up at the podium, they’re often waiting for Thompson to run out of questions.

The postseason is also when you can see one of NBA reporting’s sneakiest moves. Let’s say a player like James Harden is talking to reporters in a scrum and, across the locker room, a reporter is sidling with Carmelo Anthony. A second reporter will sometimes stand at the outer edge of the Harden scrum, close enough to hear Harden but also close enough so he can eavesdrop on Anthony’s private conversation. As Haberstroh noted, the reporter looks like he’s playing help defense.

Players like Draymond Green are aware of this trick. To fend off prying ears, Thompson said, they start speaking in code. Sometimes they drop the subject from their sentences—e.g., “Needs to play better D. Needs to get his head out of his ass.” The reporter in the sidle knows who the player’s talking about, while the eavesdropper is left in the lurch.

NBA insiders dream of the ecstatic postseason sidle, where they can smite the competition like Michael Jordan shooting over Bryon Russell. At the Finals two years ago, Haynes got a tip that James and Durant had recorded a hip-hop track together. It was just the kind of human-interest story the media was salivating for. After talking to his sources, Haynes decided to check it out with James and Durant.

Haynes remembered: “I went to LeBron before I published it and said, ‘Hey, I’m hearing about this song.’ He laughed and said, ‘Aw, man, I don’t want to comment on that, Chris. But, yeah, you’re right.’”

Next, Haynes went to Durant: “He said, ‘Man, don’t be writing that bullshit!’” Durant, who was trying to win his first title, didn’t want to talk about his musical sideline. But he did confirm that the track existed.

Satisfied, Haynes went with the story. He had sidled his way into a scoop.