Facebook unveiled on Monday its latest attempt at hardware: the Portal and the Portal+. The hands-free video-calling devices are essentially smart speakers (competing with products like Google Home and the Amazon Echo) with big, interactive screens that are being touted as the best way to feel like you’re in the same room when chatting with long-distance family and friends. Oh, and you can use Portal to order more paper towels, too.

There were rumors that Facebook planned to announce Portal at its annual F8 developer conference in May, but it appeared the company rescheduled following CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony before Congress and the fallout over the scandal related to the political data mining company Cambridge Analytica. The smoke has hardly cleared for Facebook, as privacy failures and “fake news” scandals continue to hound the social network. Perhaps that’s why now, following yet another security breach, Facebook decided it might as well introduce Portal.

But timing aside, Facebook has previously struggled to break through with hardware. Before we assess the new Portal, let’s take a quick tour of the graveyard of Facebook devices.

HTC First (2013)

You’d be forgiven if you don’t recall the device almost universally known as “the Facebook phone.” The HTC First ran a version of Android layered with Facebook’s own mobile software, called Facebook Home. Every function of the phone ultimately tied back to Facebook. Status updates from the social network frequently slid across the lock screen with a full-screen image. A feature called “chat heads” popped up over other in-app functions and connected SMS and Messenger for constant communication. There was an option to “like” things straight from a locked phone. Simply put, it was all too much Facebook, and it also handed over a shockingly large amount of data to the company. Yet in the time before Cambridge Analytica or the EU General Data Protection Regulation were in the news, there were no major outcries.

The phone flopped anyway. Instead of taking cues from the direction smartphones were going, the HTC First decided to go with a smaller screen. The camera was bad; the hardware design was average at best. But what overwhelmingly turned users off was that Facebook Home shoved the social network into every nook and cranny of the mobile experience. It was basically dead on arrival: Within months, the press cycle turned from lauding the experimental device to cataloging why it flopped.

Oculus (2014) and Oculus Go (2017)

Facebook acquired Oculus VR for $2 billion in 2014, at a time when Oculus had already managed to dominate the consumer virtual reality market. That said, the temperature on VR remains lukewarm. And while the Oculus Rift headset (the more affordable, entry-level Oculus Go was launched in 2018) may be Facebook’s best entry into hardware, it isn’t a Facebook original.

Surround 360-degree cameras (2016, 2017)

Facebook first introduced its Surround 360 camera in 2016, and launched a second-generation version of the device in 2017. The 360-degree 3D capture video camera is primarily designed to capture content to be viewed via VR headsets. It’s a highly technical, professional-level device that isn’t geared toward the consumer market, although Facebook did recently partner with RED, one of the biggest names in VR cameras.

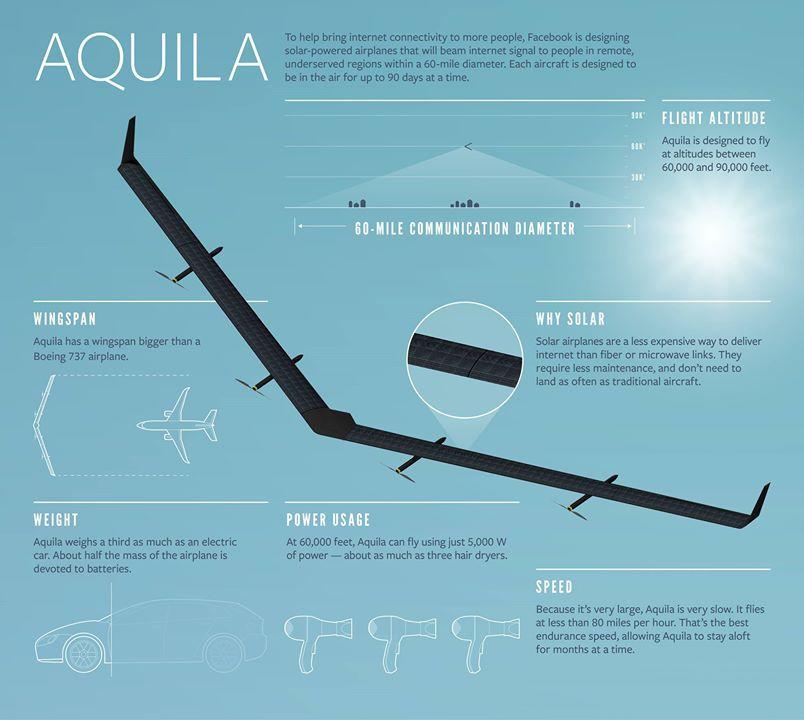

Facebook Aquila (2016)

Aquila wasn’t consumer hardware, but a solar-powered drone with the wingspan of a Boeing 737 (though much lighter). It was pitched as an internet-powering machine meant to beam Facebook’s Internet.org service down to earth and the billions of people who lack reliable connectivity. On July 21, 2016, Aquila took its first flight and was considered mostly a success, despite a wonky landing. A second test flight followed, but in June Facebook announced it would no longer be building its own drones, essentially leaving Aquila to sit idle in a hangar for good.

Portal and Portal+ (2018)

“It’s like having your own cinematographer and sound crew direct your personal video calls,” declares the Facebook release for Portal. The device uses artificial intelligence to follow speakers around during a call, panning around the room and zooming in as needed. Portal and Portal+ use Messenger to make calls, and incorporate Amazon’s Alexa so users can control the device via voice command (“hey Portal”). It integrates with apps like Spotify, Pandora, and the Food Network and also functions as a way to push the platform’s Facebook Watch streaming product, which is off to a slow and confusing start.

The 10-inch Portal ($199) and the 15-inch Portal+ (which, for $349, boasts better resolution and audio capabilities) are the newest entries in what’s quickly becoming a crowded smart speaker market. The twist is that Facebook’s pitching its product as a “video speaker,” focusing on video calls in what feels like an attempt to align it with the company’s core business mission to “bring the world closer together.” But while the social network promises that it won’t listen or look in on Portal users or store their voice commands or calls, faith in Facebook security is shakier than ever. At the moment, it seems like a very hard sell to expect consumers to grant Facebook a physical presence inside their homes.