Nick Kyrgios never makes winning look easy. In fact, much of the time he makes being a professional tennis player look exceedingly difficult, which is bizarre given that only 16 men on earth are currently more successful at playing the sport.

He struggles against superior opponents, as many athletes do. But the ATP’s 17th-ranked player also collapses against inferior competitors in ways that most supreme talents do not. If one needs a sporting reminder that the mind is part of the body, few methods are more effective than watching a match involving the 22-year-old.

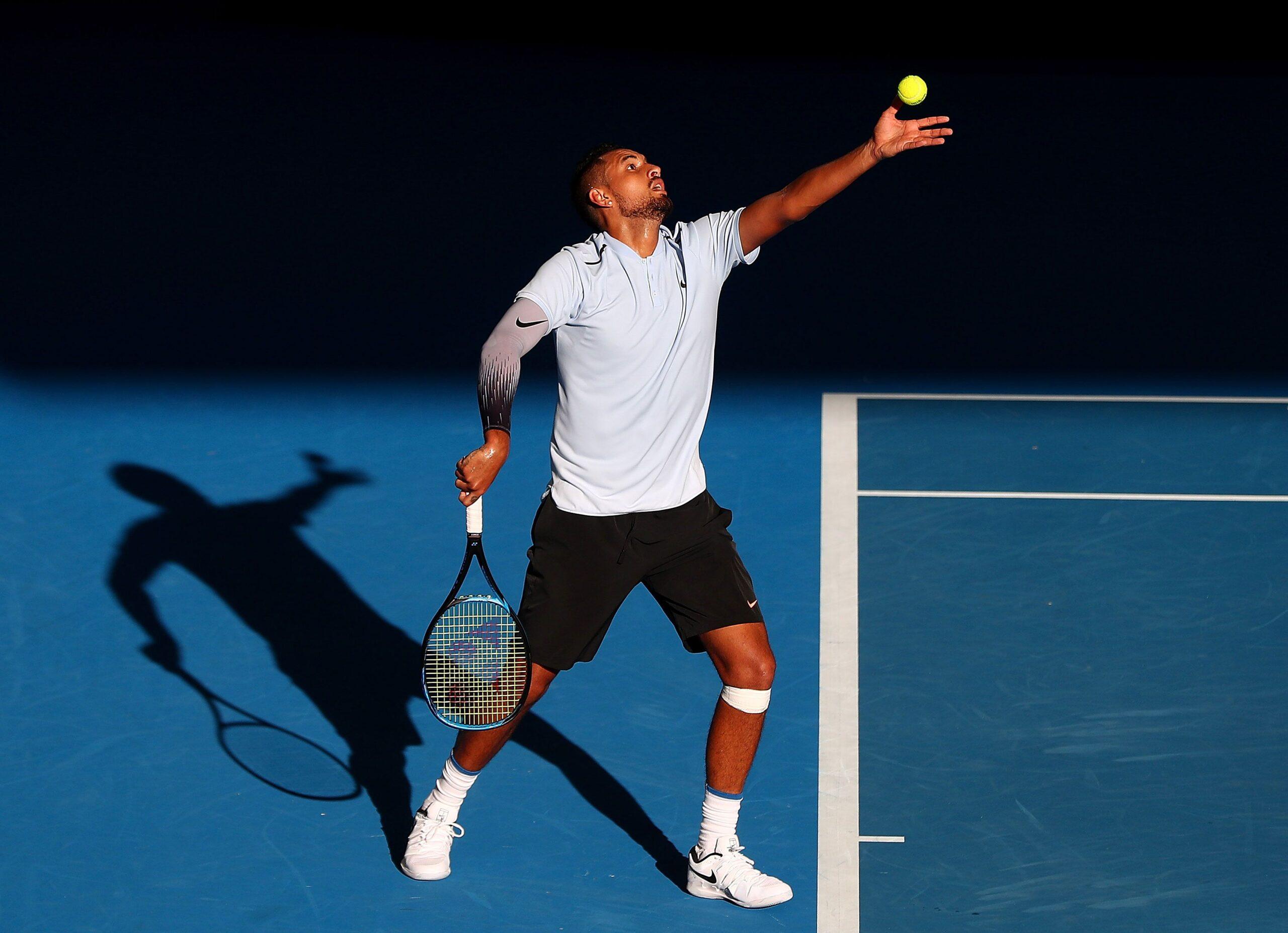

Surely you’ve heard about Kyrgios by now. He’s the Australian who has been marked as an ascendant tennis power since toppling Rafael Nadal during a run to the Wimbledon quarterfinals as a teenaged wild card in 2014. Even then, Kyrgios’s gifts were clear: He was 6-foot-4 with a massive, rocking serve and senses so acute that he could hit trick shots mid-rally for winners. He was such a natural that he could push top players despite having questionable motivation and lazy footwork. His ranking shot to the top 30 in 2015 and to a career-high no. 13 by the end of 2016.

In the years since that run at Wimbledon, though, Kyrgios has been better known for the myriad ways in which he’s upset the tennis world’s precious sense of decorum than for finding much competitive success. He’s lost interest in matches mid-contest and made obscene remarks to opponents. He’s gained a reputation as a disrespectful head case whom those around the game love to hate. He was, and still is, young, and he’s an exceptional player even with his head spinning like a gyroscope. But, unforgivably, Kyrgios has struggled at the majors. He hasn’t made a quarterfinal of a slam since the 2015 Australian Open.

Last year he flamed out in the first or second round of all four majors, most spectacularly in Melbourne after squandering a two-set lead against the then-32-year-old Italian journeyman Andreas Seppi. “Kyrgios dissolved into mess of code violations and unforced errors and in doing so, turned a straightforward match-up into a five-set horror show of scarcely believable proportions,” The Guardian read after the match. That day, the Australian left Hisense Arena to a chorus of boos led by his own countrymen.

Yet Kyrgios’s 2017 wasn’t solely defined by disappointment. Shortly after the Australian Open, he notched two wins against then-world-no. 2 Novak Djokovic and back-to-back victories over now-fourth-ranked Alexander Zverev. At the Miami Masters in April, Kyrgios faced off against Roger Federer in a rollicking, sometimes unsettling competition that was also an unrivaled display of shotmaking. Federer won in three sets—6-7 (9-11), 7-6 (11-9), and 6-7 (7-5)—but not before Kyrgios had a chance to unravel. As the final set rolled to a close, a heavily pro-Federer crowd jeered, yawped, and interfered with line calls; Kyrgios, justifiably this time, lost his shit. After leading in the final tiebreak, the Australian dropped a handful of bang-bang points, and with them, the match. His post-match trip to the net was delayed by a racket-smashing detour.

If Federer’s curt handshake was any indication, he felt similarly about Kyrgios’s tantrum as most onlookers probably did: The kid was immature, entitled, disrespectful. A brat, like the headlines had said. But Kyrgios was something else in that moment. He was vulnerable— conflicted, confused, and angry in a way that most athletes refuse to be.

That’s what makes Kyrgios such a compelling story heading into this year’s Australian Open. His potential is seemingly unbound, yet it’s unknowable whether his mind and immense physical talents will ever align on the court. He is a contradiction, an enigma, and in a uniquely open field, he has as good an opportunity as ever to win a slam.

“When I’m in that frame of mind— when motivation levels are high— I feel like I can beat anyone who steps out on the court. The match is on my racquet and the ultimate result is up to me. … It’s against the lower-ranked guys on the back courts where I can’t get it together and tank,” Kyrgios wrote in PlayersVoice last September, just weeks after falling in the first round of the U.S. Open to an opponent who had spent much of the year playing Challenger events.

This admission amounted to a mortal sin for a player who, as far as most fans are concerned, exists solely to pursue trophies and records and the honing of perfect strokes. The best athletes are supposed wake up in the morning and piss excellence, with a single-minded focus on achieving greatness. It’s only upon retirement that they’re apparently allowed to concern themselves with other stuff. If being great comes at personal expense, what does it matter? The expectation for these superstars is that their craft should take precedence above all else: Anybody can have relationships or a family; a select few can leave a sporting legacy.

This may explain why many high-profile athletes can feel so unrelatable. Traveling around the world while fixating on how to perfectly swat a yellow ball often comes at the expense of schooling and other developmentally formative experiences. The best athletes are able to be exceptional not only because of their gifts, but also because of the tunnel vision through which they pursue sporting success.

In the same way that UCLA quarterback Josh Rosen has been criticized as “too smart” for his own good and may turn off NFL franchises because he doesn’t love football enough to make for the optimal franchise quarterback, Kyrgios is upsetting to the tennis world because he—like most humans—is a ball of contradictions. Sometimes he takes the court with holy, animating fire in his eyes. Sometimes he wonders if his career choice is sustainable.

“Some days, I’m really good,” he told The New Yorker last July. “I like going out on the practice court and training with my mates. But I don’t know about fully engaging and giving everything to it. It’s just a game. It’s just a sport. It’s such a small part of my life.”

This is what makes Nick Kyrgios more interesting than any myth. He is able to crack a serve that strikes like lightning, see the ball and redirect it almost too easily, move about the court almost too quickly, and swing a tennis racket in a manner that would induce injuries in a weaker specimen. And yet he knows that on-court greatness is not the end-all, be-all. If he wins a major, he’ll still go on searching for meaning. “I can honestly say winning a grand slam would not make me the happiest person on earth,” Kyrgios wrote in PlayersVoice. “I just love being a normal guy.”

Whereas Federer is captivating chiefly because he appears to want to play tennis until his limbs fall off—his ability to stretch an all-time-great career into eternity befitting of folklore as much as reality—Kyrgios is fascinating primarily because he’s distinctly human. The idea of Nick Kyrgios and the actual Nick Kyrgios are the same: promising, infuriating, and indigestible, just like anything worth caring about.

That doesn’t mean Kyrgios isn’t eager to break through. Last September, after losing a 16-minute match tiebreak to Federer in the final rubber of the Laver Cup (the inaugural version of the tennis world’s spin on golf’s Ryder Cup), Kyrgios, representing Team World, dropped to his knees, inconsolable. It seems that he does care about tennis, sometimes.

“People around the game have trouble believing Kyrgios is really as down on tennis as he claims; they figure the ambivalence is just his way of deflecting pressure,” Michael Steinberger wrote for The New York Times in 2016. “The expectations for him are huge, and not just because he is so talented. Tennis is approaching a period of transition.”

Tennis has been anticipating this changing of the guard for years, and somehow it still hasn’t come. The sport enters 2018 with Federer and Nadal as the defending men’s singles finalists in Melbourne and the reigning champions at all four majors. The men’s singles draw at the year’s first slam is wide open, begging for a new champion of note. Andy Murray has already withdrawn from the tournament. Stan Wawrinka’s health is questionable. Novak Djokovic is seeded 14th and hasn’t played in a professional match since last July. Meanwhile, Kyrgios finally made winning a tournament look routine. He was the champion of last week’s Brisbane International, beating world no. 3 Grigor Dimitrov in the semifinals.

“Every time I stepped out here you gave me such great support. I love playing in front of you guys even though sometimes it may not seem that way,” he said to his home crowd. “But I do. I really appreciate it.”

In Melbourne, Kyrgios has been slotted into Dimitrov’s quarter of the draw. He’s a dark horse in a field full of steady, proven opponents, but there is no longer a Big Four–shaped roadblock in his path to the semifinals as there’s been in years past. At long last, Kyrgios has momentum, and it comes at a time when the field is looking weaker than at any point in recent memory.

Winning turns agnostics into believers, traditionalists into trailblazers. It can even turn so-called head cases into icons. Kyrgios enters the Australian Open looking to disrupt the state of tennis in more ways than one. He can usher in a long-awaited new era. He can also prove that being a paradox and a champion aren’t mutually exclusive.