There’s a scene in The West Wing in which President Bartlet declares to his wife that he’d have been a great astronaut. She tells him he’s wrong, because: “You’re afraid of heights, speed, fire, and small places.” For those reasons, I also never really dreamed of becoming an astronaut myself, but I’ve been fascinated by space as far back as I can remember. I was born a year after the Challenger disaster, just as the novelty of the space shuttle was wearing off and Americans were looking for that next great spacefaring innovation, one which, with all due respect to the International Space Station, never really came.

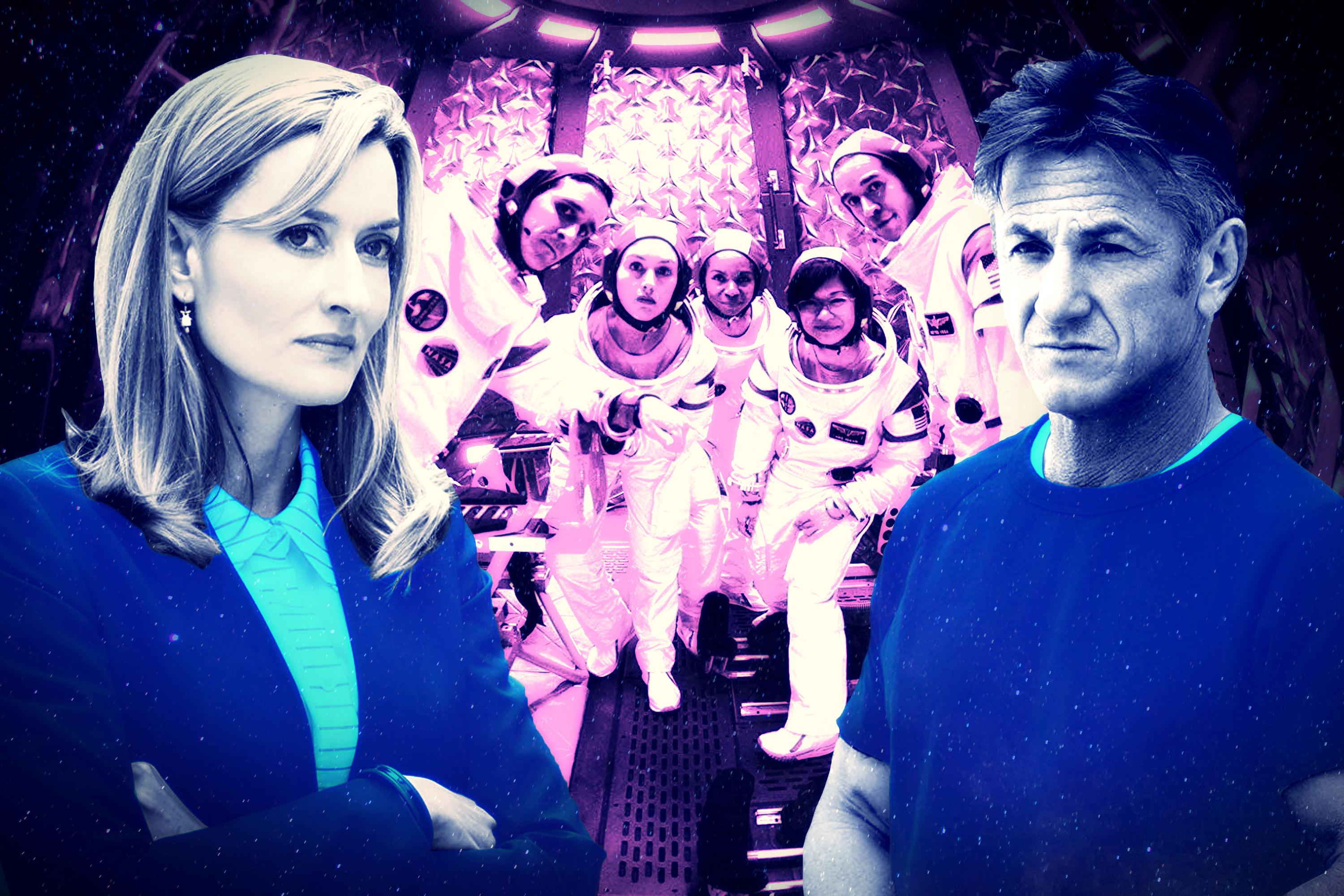

Ever since I could read I had books that predicted that we were 15 years away from putting an astronaut on Mars, and for the past 30 years, Mars has remained about 15 years away. Hulu’s new series The First is set 15 years from now, in a world in which the first mission to Mars is about to launch. The premise was so alluring I couldn’t help myself from watching The First, even though the showrunner (House of Cards’ Beau Willimon) and two lead characters, astronaut Tom Hagerty (Sean Penn) and commercial launch magnate Laz Ingram (Natascha McElhone), made me almost certain that I’d find the show repulsive.

Great NASA dramas have two kinds of heroes: astronauts and the flight controllers and engineers who make sure they get to and from their destination safely. True to form, The First’s two leads are an astronaut, Hagerty, and an engineer, Ingram. But each of them, as well as Willimon, gave me a reason to doubt the show, and elements of that fear turned out to be justified.

Hagerty is a pretty straightforward astronaut character, more or less the same as Tom Hanks played in Apollo 13, or Jessica Chastain in The Martian, or, one imagines, Ryan Gosling in First Man—a charming but serious and determined military officer. Because we spend so much more time with Hagerty than most NASA drama mission commanders, we get to know him better, and while he’s straightforward, he’s not a stock character. Hagerty has his own fears and demons, and Penn plays him with at least as much range as Hanks demonstrated playing Jim Lovell.

The problem with Hagerty as a character is that, like every astronaut worth making a movie about, he has a complicated home life. In The Right Stuff, a complicated home life meant an astronaut neglecting or cheating on his wife, while in From the Earth to the Moon, Apollo 13, and—judging by how much time the trailer spends on characters who ultimately die—First Man, it meant the fear that the heroic astronaut might die on his mission. But these are problems based on family dynamics of the 1960s—Hagerty’s family drama is much more modern.

Hagerty was the commander of the first mission to return to the moon since Apollo 17, and was slated to lead Providence 1, the first mission to Mars, until his wife drowned and his teenage daughter became addicted to heroin and ran away from home. As Hagerty, Penn plays the role of widower and single father with depth and empathy, but at the end of the day, the women in Hagerty’s life aren’t fully realized people. We see Hagerty’s late wife through flashbacks, and his daughter, Denise (Anna Jacoby-Heron), develops as a character over the first half of the season as she enters recovery. But then she relapses, suddenly, for no character-driven reason that seems as compelling as the timing being useful for the plot. These women don’t even really get fridged—they’re just obstacles for Hagerty to overcome.

But none of that is as problematic as the involvement of Penn himself. Perhaps this show doesn’t get made without the imprimatur of a two-time Oscar winner, but I kept watching Penn and trying to imagine this show with a more likable 50ish dadlike white guy in the lead role—Patrick Dempsey, maybe, or they could have popped over to First Man and borrowed Jason Clarke or Kyle Chandler.

At this point in Penn’s life, it’s tough to forget who you’re looking at. It’s tough to forget the weird seriousness, and serious weirdness, that’s followed Penn throughout his forays into diplomacy and amateur gonzo journalism over the past decade. It’s also tough to forget Penn’s propensity for physical violence as a young man, including allegations that Penn physically abused his ex-wife, Madonna—particularly during a scene in which Hagerty, in the midst of an argument with Denise, backs her up against a wall and breaks a picture frame hanging by her head. Penn, gifted actor though he may be, is not the only person who could have played this role, and his involvement complicates the production.

McElhone’s Laz Ingram is the opposite—an inoffensive actress playing a deeply problematic character. Great NASA dramas foreground the heroism not only of the astronauts who go to space but the engineers who keep them alive once they’re there. After all, the most memorable performance in Apollo 13 is Ed Harris’s Oscar-nominated turn as flight director Gene Kranz. But the real-life Kranz is an aerospace engineer and career civil servant, while Ingram is the founder of a tech startup, Vista, the commercial launch company behind the Providence program.

Jarring as that shift is, it does reflect the realities of spaceflight in 2018. After decades of owning and operating its own crewed spacecraft, NASA has begun to hire subcontractors to ferry supplies, and soon, astronauts, to the International Space Station. This represents a marked change in NASA policy, though not a total privatization of spaceflight. Rather, it’s a cost-cutting measure that NASA can take now that orbital spaceflight has become, to a large extent, routine. NASA, should it ever undertake crewed planetary spaceflight in the future, plans to own and operate its own vehicles, as it did in the Apollo program.

When we see Providence 1 lift off in the pilot episode, it resembles NASA’s planned Orion capsule and SLS rocket, but it’s festooned with Vista branding, and Ingram, not a NASA administrator, is in charge of program operations. The astronauts wear NASA-branded golf shirts, and Hagerty testifies before Congress in a U.S. Navy uniform, but it’s made clear that Ingram personally recruited both the mission commander and the program’s chief engineer from NASA to work for her. She’s not a contractor; she’s in charge.

Maybe it’s a concession to reality that the lead ground-crew character is a businesswoman first and foremost, and not a 2030s version of Chris Kraft. Truth be told, if an American spacecraft gets anywhere near Mars in the next generation, it will be because some private company does a ton of lobbying and a ton of the legwork, because the political will simply doesn’t exist to press the U.S. government to explore space now the way it did in the 1960s. (While NASA hasn’t sent anyone to the moon in 45 years, three days after The First premiered, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced that he’d be sending Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa, essentially a tourist, to space to become the 25th man to orbit the moon, and God willing, come home alive.) In Willimon’s show, that means not only an increased privatization of space exploration, but a blurring of the lines between corporation and government, to the point where it’s difficult to tell where Vista ends and NASA, or what’s left of it, begins.

Now, just because this is the world Willimon predicts doesn’t mean it’s fair to paint it as his ideal—indeed, in the world of The First, many of the crises that plague American society in 2018 have either gone unsolved or only gotten worse by 2033. But it’s clear from the way Ingram is portrayed that she’s supposed to be right, and that she isn’t supposed to represent the kind of flawed space entrepreneur we see today. In fact, in many ways, she’s a rebuke of Musk.

The show’s sixth episode, “Collisions,” is centered on Ingram’s interview with a skeptical New York Times reporter, who says she’s publicity-averse, unlike some of her competitors, which could not be a clearer subtweet of Musk. And crucially, Ingram’s primary goal appears not to be building a cult of personality or generating internet LOLs, but actually sending people to Mars—and in the first season, she at least gets far enough to begin a credible attempt.

Furthermore, Ingram gets two episodes in which to explain why she’s right, one centered on a congressional hearing, the other on an interview with a New York Times reporter, like the history and moral philosophy class in the novel Starship Troopers. At one point, a hostile senator puts it to Ingram that the $70 billion spent on the Providence program might be better spent on social welfare programs. But while Ingram makes her case for a mission to Mars on humanitarian grounds, it never occurs to any of the characters that the government might raise $70 billion for social programs by other means; say, by reducing military spending or taxing the Laz Ingrams of the world more. Some things are harder to imagine than going to Mars.

The inelegant execution of the argument is just as frustrating as its unimaginative political foundation. That brings us to Willimon, a screenwriter I’ve found frustrating ever since his first credit, the 2011 film The Ides of March, which is based on Willimon’s play Farragut North, which is in turn informed by Willimon’s previous career as a Democratic political operative. Willimon was nominated for an Academy Award for The Ides of March, but he made his bones as the creator of House of Cards, a show that showed promise early on but quickly descended into self-parody.

Joe Klein is another author who used his real-world political experience to write the source material for a screenplay about a creepy conservative Southern Democratic presidential hopeful, in his case Primary Colors. In his afterword to Primary Colors, Klein tossed off a line that’s stuck with me since I first read it a decade ago: “[C]ynicism is what passes for insight among the mediocre.”

I’ve had a complicated relationship with that quote, because in many cases, cynicism is a useful tool for screenwriters and journalists alike—to say nothing of moviegoers and voters. Some people’s motivations are worth examining, and some institutions deserve to be instinctively trusted. But that quote also reminds me of Willimon’s work, which frequently clothes itself in the trappings of profundity without saying anything interesting itself. And sometimes, the dim lighting, weighty monologues, and sinister antiheroes are enough of a distraction that you don’t ask yourself what’s underneath. But frequently, it comes off as a shallow and uncanny facsimile of good TV.

Willimon’s made a career of putting out things that look enough like good film or television to fool people into thinking they’re actually good television, and I was worried that, in combination with Penn’s brand of pretentious weirdness, the explosion of Providence 1 in the premiere would end up as a microcosm of the whole.

And while there’s some of that—much of the show is dark and blue, and there are lots of shots of Captain Hagerty working out with his shirt off, his creepy, veiny Old Man Muscles bared to the elements, and there are persistent interstitial shots of a dude putting together an old-timey telephone for reasons passing understanding—it doesn’t derail the show.

I went into The First expecting, almost hoping, to hate it, and I came out liking it, because it captures the magic of the NASA drama.

When my colleague Miles Surrey wrote about The First earlier this week, he bemoaned the fact most of the action takes place on the ground, even going so far as to say the program’s earthbound nature “should be a fatal catch.”

The thing about contemporary or near-future semi-plausible NASA dramas like Interstellar, The Martian, or even Armageddon, is that the drama ends up taking place in space precisely because they’re works of fiction. In reality, astronauts have very little room to improvise once they leave Earth. Their every movement is choreographed months or years in advance, every contingency accounted for, every potential pitfall anticipated. The limited freedom astronauts work with is what made The Martian such an interesting story to begin with—the greater the constraints, the more impressive the improvisation. In reality, most of the drama involved in spaceflight takes place on the ground, and when something does go wrong in space, so does most of the problem-solving.

The First does a great job of making the legwork of spaceflight interesting and dramatic, with the help of an exceptional supporting cast that’s one delightful “Hey, it’s that guy from that thing!” after another, including James Ransone (The Wire) and Keiko Agena (Gilmore Girls) as astronauts and Oded Fehr (The Mummy) as the program’s chief engineer. In this respect, it resembles more than anything else From the Earth to the Moon, the 1998 HBO dramatization of the Apollo program, and in fact lifts several story lines straight from the older program. In both shows, the second episode is devoted to congressional hearings to save the program after the first mission’s crew is killed. Later in the series, an astronaut is scrubbed from a mission due to an issue with his ear, another astronaut has to work out a professional rivalry with the mission commander, and still another astronaut struggles with leaving his troubled family behind—all of these are also story lines in From the Earth to the Moon.

But I don’t care, because they’re good story lines, and The First has no shortage of compelling earthbound human drama, including my favorite story line. When Hagerty’s reassigned to command Providence 2, it has the knock-on effect of bumping the mission’s previous commander, Kayla Price (LisaGay Hamilton), out of the big chair, and scientist Sadie Hewitt (Hannah Ware), off the mission altogether. Price, who’s as much a buttoned-down military pilot as any astronaut in TV or movie history, must deal with her own feelings about being demoted when they come into conflict with her respect for the chain of command—a struggle that’s all the more complicated when she considers that she, a queer black woman, has been asked to make room for a white man.

Price had previously recruited Hewitt for Providence 2, and Hewitt, once uncertain of her qualification for or desire to become an astronaut, is heartbroken when she’s not only left off the mission roster, but asked to help train her replacement. Meanwhile, her desire to go to space is so great that she’s unable to consider whether she wants to have children, which is something her husband, who put his career on hold while she trained to fly to Mars, wants badly enough that it strains their relationship.

Few people can truly identify with the thrill and adventure of space travel, but almost any viewer can put themselves in Kayla’s or Sadie’s shoes, because just about everyone faces similar doubts or anxieties about their career or their relationship. That shared humanity is the strength of The First, and that’s why the show benefits from spending so much time on the ground—space travel is just a hook, a reason to care about characters who turn out to be the emotional core of the show.

The First is at its best when it strays away from its two leads and plays up the juxtaposition of the relatability of its supporting characters and the enormousness of the goal they aim to accomplish, which is going to Mars. That’s why spaceflight is so inspirational in the first place; talented and driven people, but people nonetheless, can come together to do difficult and important things. The First, for all its faults, understands that perfectly.