The NFL is experiencing a tie outbreak. Maybe you think that ties are outdated, a rarity that will never happen to your team. But as I’m about to show you, ties are making a comeback—and we all must remain vigilant.

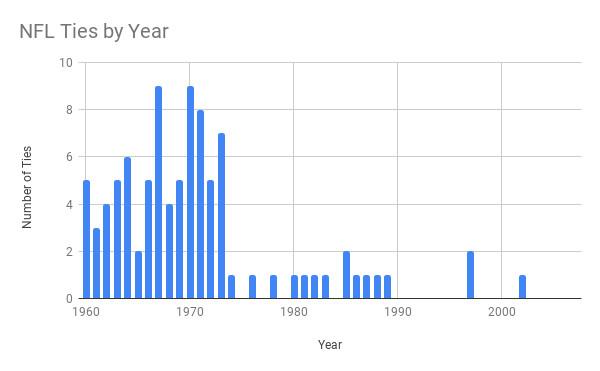

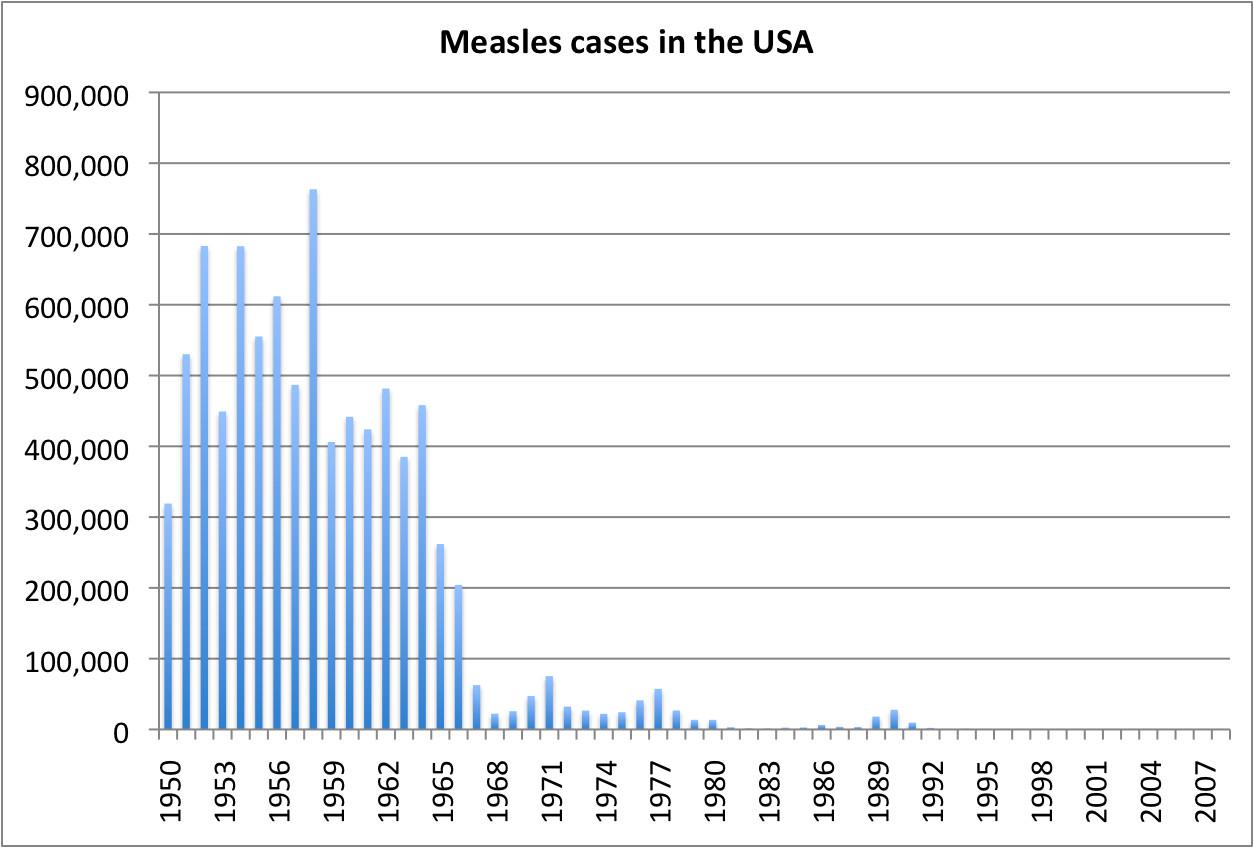

Here is a chart of ties in the NFL from 1960 to 2007. Below that, I have embedded a chart produced by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention immunologist Dr. Ian York detailing the number of measles cases in the United States from 1950 to 2007.

Measles used to be a common disease in this country, with hundreds of thousands of cases per year. But in the 1960s work began on a treatment, culminating in the development of the MMR vaccine in 1971. As you can see from the chart, widespread vaccination essentially ended the disease. In 2000, the CDC declared that measles had been eliminated.

The NFL could have declared ties eliminated in 2000, too. The tie used to be a common result for NFL games, peaking in 1967, when the league had a whopping nine ties during a regular season consisting of just 112 games. Then, in 1974, the league introduced a ties vaccine—overtime, ensuring that if regulation ended with the score even, the teams would keep playing. As you can see from the chart, widespread vaccination essentially ended the tie. From 1990 to 2007, there were only three ties, despite the number of NFL games increasing to more than 250 per season.

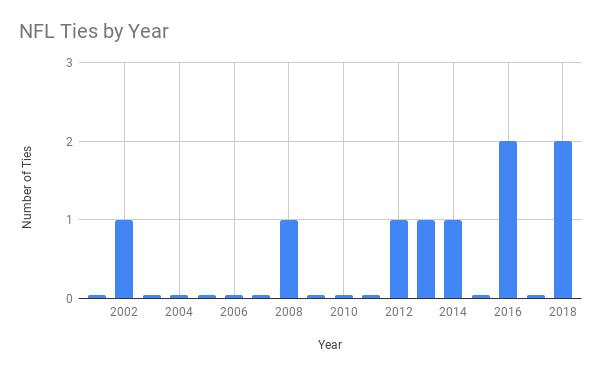

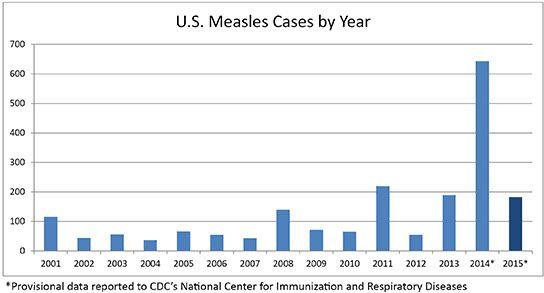

But something weird has happened in the past decade. Measles and ties are both on the rise. Here is a chart of NFL ties from 2001 to 2018, as well as a CDC chart of measles cases in the United States since 2001.

The chart undersells the current tie outbreak. Two weeks into the 2018 season, there have already been two ties: The Browns and Steelers played to a 21-21 stalemate in Week 1, and the Vikings and Packers played to a 29-29 draw in Week 2. I expect there to be at least one more tie over the final 15 weeks of the season; if that happens, this will mark the NFL’s first three-tie season since the tie vaccine known as overtime was introduced.

The uptick in measles cases is partly the result of belief spreading that the more-or-less nonexistent risks of vaccination outweigh the benefits, which are proved by decades of evidence showing that widespread vaccination leads to virtual eradication of the disease. The uptick in NFL ties also stems from a strange and sudden reevaluation of previously successful tactics.

In 2012, the league introduced a “modified sudden-death” overtime; although NFL overtime had long ended after the first score, a made field goal on an overtime-opening drive would no longer immediately decide a game. Unless the team that opened the overtime period with the ball scored a touchdown on that initial possession, the opposing team would get the chance to respond. This change led to more ties, since there was newfound potential for both teams to hit overtime field goals. It also inherently made the average overtime longer, since field goals no longer automatically ended the game. But the league decided it didn’t like longer overtimes, so in 2017 it cut the length of OT from 15 minutes to 10. The league now has the most prolonged method of determining an overtime winner and the shortest overtime session in history. It’s the perfect recipe for ties.

There is, of course, a rather large difference between measles and football ties. One is an infectious disease that still kills tens of thousands of people per year in areas of the world where immunization is not widely available; the other is a disappointing result for a sports game. I would also like to point out that this is one of the ultimate examples of how correlation does not imply causation. Despite the similarity of the charts, I do not believe there is a link between measles outbreaks in America and NFL ties. The only connection is that both were seemingly eliminated from this country by effective prevention methods, and both have, by the choices of a few, been brought back to life.

After decades of immunization, we’re not quite sure how to handle ties. In fact, some professional football players aren’t even aware that games can end in ties. The most famous example is Donovan McNabb, who admitted in 2008 that he didn’t know tying was possible after participating in the league’s first tie in six years. (A large swath of his Philadelphia teammates also had no idea ties were a thing.) But years after McNabb was mocked for this, others still didn’t know about ties. Washington head coach Jay Gruden said in 2016 that he didn’t know about ties until shortly before his team was involved in one, and last week Minnesota running back Dalvin Cook acknowledged that he was confused by his team’s tie.

It’s easy to be horrified by the return of the tie. Ties, as the adage goes, are like kissing your sister—a true dilemma, because we all love smooching but hate incest. Who wants that?

But I want to come to the defense of the football tie. I’d hate to be a fan of a team involved in a tie, but as an impartial observer I appreciate the football disasters that lead to the sport’s rarest result. And apparently I’m not alone: On Monday, I asked my Twitter followers if they thought ties were awful or a potentially intriguing outcome. There was only one possible result:

The most controversial American sports tie of the 21st century was the 2002 MLB All-Star Game. After 11 innings, both the American and National League teams had used up all of the pitchers on their rosters, and by rule those pitchers weren’t allowed to re-enter the game. So then-commissioner Bud Selig announced that the contest would end in a 7-7 tie. Everybody hated it. If the game could end in a tie, didn’t that make it meaningless? MLB attempted to fix the problem by awarding the league that won the All-Star Game home-field advantage for the World Series in subsequent seasons—this time, it counts—but that assigned too much importance to the game. With the insignificance of the event exposed to all, the MLB All-Star Game has swiftly declined in popularity. One of the most beloved events on the American sports calendar was driven into irrelevance by the fact fans couldn’t handle even an exhibition ending in a tie.

Every major American sports league has gone to great lengths to eliminate ties. Basketball games can go on indefinitely, with the NBA tacking on five additional minutes of play until one team has more points than the other. Baseball games can continue on forever as well—even though ties would prevent teams from routinely depleting their bullpens. MLB teams play 162 games per year! A team that wins 81 games has a winning percentage of .500; if a team went 81-80-1, it would have a winning percentage of .50308. Y’all are really out there having your backup catchers pitch to potentially gain .003 in the standings? The NHL got rid of ties in 2006, installing a brief overtime session with fewer skaters to encourage goals, and then a shootout, although teams still receive a point in the standings for losing in overtime. MLS, like other major soccer leagues in the world, has ties, but even that league worried about American distaste for the draw—early MLS games had hockey-style shootouts, which, quite frankly, were awesome.

Eventually MLS embraced the tie, because as soccer fans will tell you, draws aren’t meaningless. Some are stunning results for minnows against massive favorites; some go against the run of play, with the team that looked worse somehow coming out even against a team that clearly deserved to win. Some are games in which both teams are so damn good that it has to end in a tie. My favorite match of this year’s World Cup: Spain 3, Portugal 3.

This is a mind-set soccer fans had to adopt, because ties in that sport are too common to avoid. They happen in somewhere between 15 and 30 percent of matches in top-flight leagues. That’s far from the case in football, where ties are still rare enough that some players aren’t entirely sure they exist.

And that’s why I think football fans can come to love the tie. Even under the most tie-friendly rules in decades, we won’t see ties every week. They’ll come around only every once in a while, when both teams put on performances that deserve to unlock a new column in the standings. Browns-Steelers and Packers-Vikings were both spectacularly unfortunate games, in which the teams should have been aggravated by their inability to win. They featured multiple missed would-be game-winning field goals—in fact, Browns kicker Zane Gonzalez and Vikings kicker Daniel Carlson have both since been cut. Cleveland somehow managed to tally six takeaways without coming away with a victory, putting it among an incredibly small group of teams capable of squandering such a magnificent defensive performance. The Browns experienced the joy of avoiding a loss after going 0-16 last season, but also the frustration of not securing a win after playing so well. Pittsburgh blew a 14-point fourth-quarter lead, and had an overtime fumble in addition to its missed field goal. And, well, there’s no positive spin that comes with failing to beat a team fresh off an 0-16 campaign.

The Vikings rallied from a 13-point deficit to notch a tie last week thanks to a play of the year candidate, this Kirk Cousins pass to Adam Thielen:

Minnesota successfully iced Green Bay kicker Mason Crosby before he attempted a potential game-winning field goal, but then watched as Carlson duffed two kicks in overtime, including one from 35 yards right down the middle of the field.

Both games were combinations of unusual football events that culminated in the ultimate unusual football event: a split decision. All parties involved were at least somewhat disappointed—and for fans of the other 28 teams in the league, that’s basically ideal.

There is a better option. The other levels of football in the Americas—in the college and high school ranks—have eliminated ties by adopting a form of overtime that was pioneered by Kansas high schools. It is superior to the NFL’s overtime system in virtually every way. An overtime period consists of each team getting one drive that starts at the opposing 25-yard line. The overtime periods continue until one concludes with one of the teams having more points than the other.

This is easy to explain and understand. Meanwhile, we’re now seven seasons into the NFL’s modified sudden-death system, and each overtime period still begins with an official reading the team captains a novella about the rules so nobody messes up. College and high school overtimes typically wrap up within a few minutes of real time, and they’re designed to produce dramatic moments. Take last season’s College Football Playoff national championship game.

Pro overtime is ugly. Exhausted offenses try to drive the length of the field while simultaneously burning enough clock to prevent the other team from mounting a scoring drive in the newly condensed period. College overtime has a sense of urgency; pro overtime is mostly fatigue and risk mitigation.

I suspect that the NFL is too haughty to ever adopt the college overtime rules, because it’s more mini-game than real football. Heaven forbid that overtime takes the most exciting parts of a football game and emphasizes them. Instead, we get to watch real football—real, sloggy, ugly football. (The overtime drive chart from that Steelers-Browns matchup: punt, punt, punt, missed field goal, punt, fumble, missed field goal, end of game.)

The NFL has chosen to have ties. Nobody asked the league to do this; heck, the powers that be probably didn’t intend for it to happen. But that’s the choice the league made. Remember this every time you see a tie—and I promise you, if the rules stay the same over the next few years, you will see more ties than you have seen in your entire life.

That leaves us with one choice: love the tie, or hate it. I suggest we choose the former. We have seen most football wins and losses before, but every tie is unique because of how disastrously things have to go to get there. We can appreciate the rarity and misfortune of these games, so long as our team isn’t in them.