King Football Still Reigns. But for How Long?

On the eve of the NFL’s 99th season, the league is plagued by political panic, CTE anxiety, a war with the president, and shrinking ratings. But it’s still the most popular sport in the country, by a wide margin. Is football holding steady or destined for a slow, ignominious death?I suppose if the doomsayers and cultural critics are right, and football’s long period of primacy is finally starting to wane, we may all look back a few decades from now and decide that the absolute apex of the National Football League’s cultural hegemony was Sunday, February 4, 2007.

A little after 8 p.m. that evening in Miami, Prince concluded his halftime concert at Super Bowl XLI with a glorious version of “Purple Rain,” performed in a driving rainstorm. On the biggest stage in American entertainment, one of the coolest people in the world delivered a transcendent performance, aided by a timely assist from Mother Nature. Then we all settled in to watch the second half of the biggest football game of the season.

But it wasn’t merely those 12 minutes of Prince-powered pop cultural bliss. The game itself—Colts vs. Bears, outdoors on natural grass—was compelling, even historic. Peyton Manning won his first championship, and, in the first Super Bowl between two African American coaches, the Colts’ Tony Dungy triumphed. The backdrop of the game was a weeklong testament to pro football’s place in the American zeitgeist.

It wasn’t as if the NFL could do no wrong in 2007. But its preeminence was accepted as a matter of course. It was difficult to be a culturally literate American without at least casually following the game. Condoleezza Rice, president George W. Bush’s national security adviser, famously said her dream job was to be commissioner of the NFL. Football was everywhere, not only on ESPN and the pages of Sports Illustrated, but throughout culture. In the fall of 2006, reviewing Justin Timberlake’s FutureSex/Love Sounds in The New Yorker, Sasha Frere-Jones pondered the single “SexyBack” and mused, “Does anything need bringing back less than sexy? It’s like proposing to bring back petroleum, or the N.F.L.”

That was little more than a decade ago, but it seems longer now. Since then, the NFL has weathered “Spygate”; Michael Vick’s dog-fighting conviction; “Bountygate”; Jovan Belcher’s murder-suicide; the interminable “Deflategate”; the documentary League of Denial; Aaron Hernandez’s arrest and murder conviction (he, too, later died by suicide); the movie Concussion; a series of poorly handled league investigations of domestic violence involving players, followed by backpedaling and damage control after more information was made public.

And that was all before Colin Kaepernick took a knee.

Now, as the NFL begins its 99th season—and the third season of what may become known as the Anthem Controversy Era—there is a vexed uncertainty in the air. In talking to owners, general managers, and coaches, as well as executives at both the club and league levels (all of whom spoke to me on the condition of anonymity), one gets a sense of the unease around the game. Even TV ratings, that most reliable indicator of NFL dominance, were down 9.7 percent last year, after falling 8 percent in 2016.

There is also a feeling among many people in the game that the NFL can’t seem to manage a narrative anymore and too often finds itself behind the curve of public opinion.

“The league is always playing this eternal game of defense,” said one coach. “Everything feels slow, defensive, reactive.”

And then there is the larger existential threat: the growing, inexorable realization that head injuries in the NFL are far worse than many football fans suspected even a decade ago, and that the NFL has been, at best, slow to recognize and address this problem. One could argue that the image of the league itself has never been worse.

I don’t think we should be a business based on maximizing return on investment. We should be a business based on maximizing the enjoyment of the game, making it the best game it can be.NFL executive

Of course, there’s another way to look at this: In terms of revenue and ratings, the NFL’s “sick” still looks a lot better than anyone else’s “healthy.” Pro football is, by any measure, still America’s most popular sport, by a more than 3-to-1 margin in the most recent Gallup survey. Most NFL stadiums are filled nearly to capacity, no mean feat these days. While TV ratings for the NFL may be down, TV ratings for everything are down; the NFL still accounted for four of the top five most-watched television shows in 2017, and 37 of the top 50. It seems likely that the next round of television contracts will be even more gargantuan than the last. Few things have ever been as consistently lucrative in any context as pro football is on TV.

There is validity in that perspective. But what’s undeniable is that something in the air is changing around football, and if you buy tipping points and broad social trends, you might wonder whether, even as the numbers and the TV contracts continue to grow, the game’s popularity has already crested.

King Football still reigns. But for how long?

The purpose of a sports league, beyond earning money, is to conduct itself in a way that promotes the sport, increases interest in and enthusiasm about it, and generates a feedback loop of positive publicity. Great players, attractive teams, exciting games, sensible rules, compelling playoff races, good deeds on and off the field, cooperation at the bargaining table. The NBA is the prime contemporary example of this. Through its promotions, through its charity work, through its canny media relations and its mostly cooperative relationship with the players association, the NBA has used its soft power well.

But the NBA didn’t invent soft power for sports leagues. The NFL did, more than 50 years ago.

That’s when commissioner Pete Rozelle announced the formation of NFL Films. Under Ed and later Steve Sabol, NFL Films burnished the league’s reputation, appealed on an aesthetic level, and added an inestimable degree of prestige to the game and its players. It changed the way people wrote about and thought about pro football. As a business enterprise, the division didn’t always justify itself on the bottom line, but that was OK with Rozelle. He knew NFL Films enhanced the league’s perception in varied and ineffable ways.

Rozelle, generally regarded as the best commissioner in sports history, had an uncanny knack for knowing not just where the game needed to be but also where it was going. In the summer of 1969, at a time when the league had just decided how to align for the post-merger years, into two 13-team conferences, Rozelle was asked about the future of the league. He said that sometime later on, the NFL would have 32 teams, in two 16-team conferences, each divided into four four-team divisions. Thirty-three years later, that exact structure came to pass.

Rozelle often spoke to his staff about the importance of conducting the league’s affairs in such a way that fans could focus on the game itself. The football news that drew fans away from actual football—player discipline, union vs. management squabbling, strikes, lockouts, drug use, steroids, lawsuits—served only to come between the fans and the reason they watched: the love of the game.

This is, to put it mildly, something the NFL has struggled with as of late, nowhere more spectacularly than in the ongoing debate over the handful of players who have chosen to take a knee during the playing of the national anthem to protest racial and social injustice.

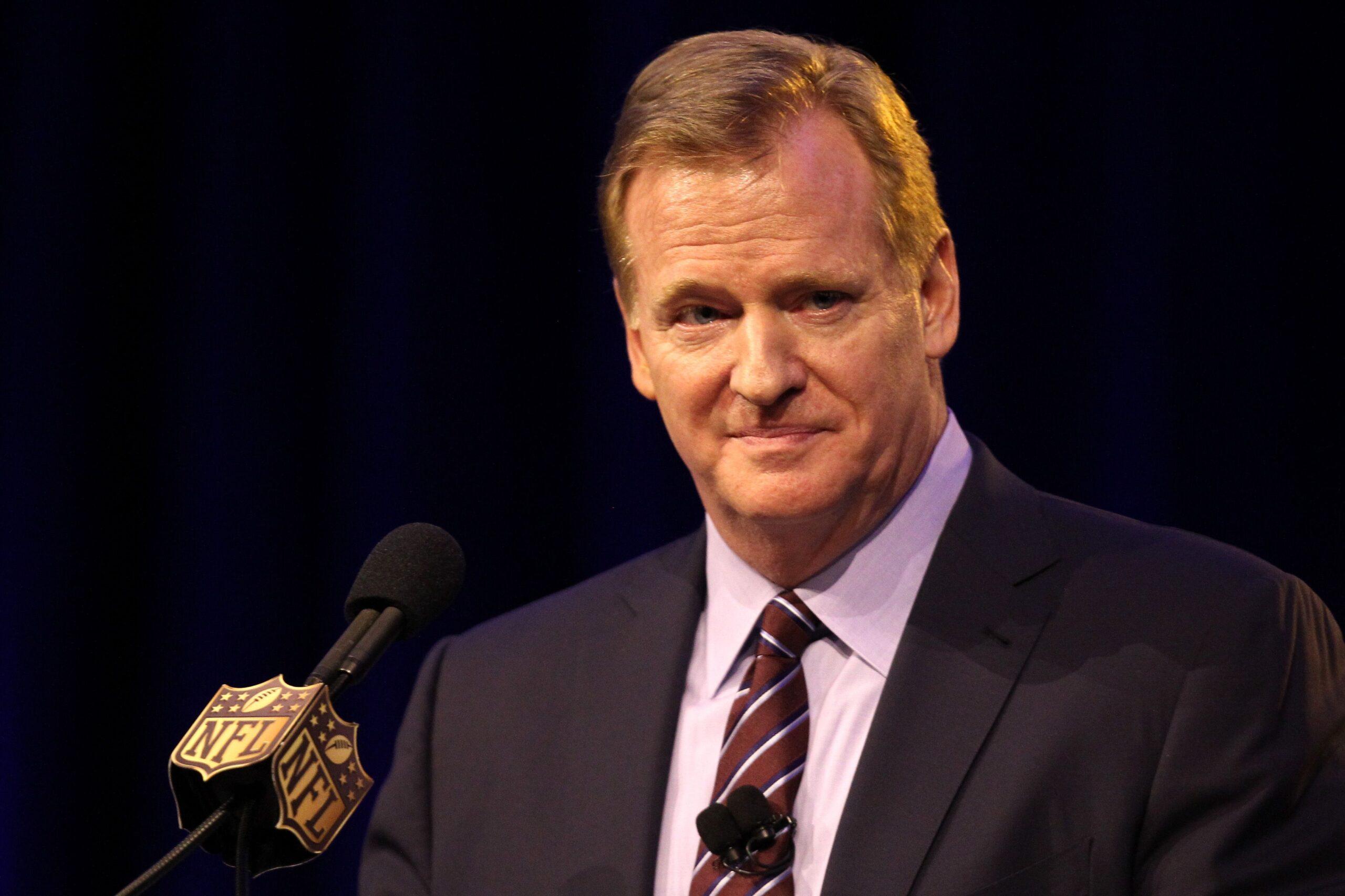

Fine margins in public perception matter. In the NBA, 100 percent of players stand for the anthem, and Adam Silver is credited with being the most effective commissioner in pro sports. In the NFL, a vast majority of players stand for the national anthem, and Roger Goodell can’t seem to go anywhere in public without getting vociferously booed like a heel in a wrestling show.

For the NFL, that small percentage has become the bloody hill on which a bitter and protracted—perhaps unwinnable—cultural war is being fought. The league and its owners held a meeting in May and hammered out a compromise that would allow players to stay in the locker room during the anthem. Then they seemed surprised—and even a little taken aback—when the compromise was instantly and widely criticized, not least because they hadn’t bothered to even consult the players they were supposed to be compromising with. The league soon backtracked from its new policy, and is doing what it needed to do in the first place—trying to come up with a solution that the players can live with as well. This wasn’t the NFL’s first misstep in the controversy.

“We botched this from day one,” said one retired club executive. “Everything we do, we keep making it worse.”

There are a lot of reasons for this, and most have been well-documented. You can blame the modern media universe, you can blame the owners, you can blame the president (a few in the league are convinced that the main reason Donald Trump has been so critical of the NFL is because he’s still mad that the owners wouldn’t let him join their ranks when he owned the USFL’s New Jersey Generals in the ’80s).

It’s significant that after two years, the league still seems unsure about what to say or how to publicly handle this controversy. The only thing everyone agrees on is that they’re tired of the problem.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve heard, ‘Why do we always have to deal with this?’” said one club executive. “You know, ‘Why doesn’t the NBA have any of these problems?’”

The short answer is that the NBA’s rule book includes a requirement that players stand for the anthem. But there’s more to it than that. As reported by the Washington Post, the NBA chose to be proactive about the potential problem and in September 2017 sent out a joint statement to its players, co-signed by Adam Silver and NBPA executive director Michele Roberts, reminding players that “Critical issues that affect our society also impact you directly… you have real power to make a difference in the world, and we want you to know that the Players Association and the League are always available to help you figure out the most meaningful way to make that difference.”

Suffice it to say that a similar show of unity between NFLPA chief DeMaurice Smith and Goodell has proved elusive.

So the protests during the anthem have gone into the rhetorical meat grinder of 21st-century America, when partisans define themselves largely by what they despise and take exaggerated umbrage over any perceived slights. Or, as the scholar Gerald Early wrote last year, “To make a black person on his knees symbolize defiance is perhaps one of the singularly stunning feats in recent American racial history!”

The divisiveness in the country over the protests shows no signs of abating, and the disagreement within the NFL could have serious repercussions. In a league in which two-thirds of players are African American, it is becoming conventional wisdom that the largely white owners and executives don’t understand their players or share their concerns.

This may not be the reality, but it is the perception, and in this instance the perception is at least as important, because these are the assumptions that the Players Association will bring into negotiations with the league when the current collective bargaining agreement ends after the 2020 season.

One veteran club executive described Goodell and Smith as “like fire and gasoline together” and speculated that the coming negotiation is “going to be a battle royale.”

“We have a horrible relationship with the players,” said one longtime league executive.

It’s been 31 years since the NFL has had a work stoppage that caused it to lose any regular-season games. But you may be able to hold your fantasy draft a good deal later than usual in 2021.

Next year, the NFL will celebrate its 100th season with myriad centennial programs, books, and features. And there will be inevitable think pieces about what football “means” in America in the 21st century. Many of these will blame Goodell for the league’s present problems.

This is both inevitable and probably unfair. Goodell has taken the criticism on behalf of the owners of the 32 teams who pay his salary. “I think the owners are just fine with this,” said one coach. “They’re comfortable having Goodell as the fall guy.”

Some of the criticism Goodell brings on himself. On the first night of the 2018 draft, answering a question about whether the Competition Committee finally got the definition of a legal catch right, Goodell blandly stated, “Fans want more catches,” as though the question was one of supply-and-demand, of legislating quarterback accuracy, rather than the more complicated challenge of how to make replay reviews quick, transparent, and consistently accurate.

As a public speaker, Goodell is a little like Hillary Clinton: He has trouble accessing and conveying his conviction. He could be talking about something he feels passionately about, something that is precious and essential to him, and his speaking style will still come off as stilted, calculated, sterile.

But it’s hard to argue with the bottom-line results. Goodell got the job in 2006 because he knew the league—the NFL is the only employer he’s ever had—and because enough big-market and small-market owners, old and new, believed he could be a consensus builder.

His job is exceedingly difficult, as he is perpetually trying to bridge the gap between hypercompetitive capitalists like the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones, who would, if he could, sell naming rights to clouds passing over AT&T Stadium, and hypercompetitive purists like the Bengals’ Mike Brown, who turned down millions so he could name the team’s stadium after his legendary father.

The league has continued to prosper by generating enough money to appease the Jerry Joneses of the world while maintaining enough revenue-sharing to allow the Mike Browns to remain competitive.

But at times it seems like the league’s solution to almost everything is to generate more revenue. “It’s way out of control,” said one club executive. “They generate every dollar they can at the expense of the game.”

This has, in fact, become something of a collective mind-set.

I can vividly remember my first meeting with Goodell. It was the summer of 2002, and I was in my third year of reporting for my book, America’s Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured a Nation, which would be published two years later. I was having lunch with Goodell, at the time a rising figure in league circles, and the NFL’s canny veteran PR man Joe Browne, trying to get some sense of how the people at the league office viewed the game.

I mentioned my idea that there was perhaps a market for making the All-22 “coaches’ tape” available to the general public, because there was a small but attentive subset of fans eager to better understand the game and their favorite teams’ strategy and tactics. They both seemed skeptical of that idea. Then I mentioned that it would be nice if the Sunday Ticket package was more widely available, so that millions of dislocated football fans would have a choice besides sitting in the corner of a sports bar, watching an out-of-market game on a small screen with no sound.

This issue Goodell took up with more interest. “We’re not doing enough there,” he said. “We need to do more to monetize Sunday Ticket.”

I may have winced. I had never heard the word “monetize” before, but I knew exactly what he meant. In 2014, DirecTV renewed its exclusive distribution deal with the NFL for Sunday Ticket—at $12 billion for eight years—so history would show that Goodell was right about further monetizing the service.

These days, of course, the NFL monetizes everything.

But there is a point when “monetization” becomes a parody of itself. Everyone has their own outrage, the moment when, as one club executive put it, “all the advertising, sponsorship, and clutter” begins to get in the way of the game itself, in distracting and ludicrous ways. Mine occurred the first night of the 2018 NFL draft, as Fox and the NFL Network and ESPN were broadcasting the league’s 83rd annual selection meeting. During the first round, we got glimpses into the “war rooms” of several NFL teams. The league had sold sponsorship for even these discrete shots to a Japanese automaker. Standard practice in this era.

But that was not enough for the New York Jets, who went a step further. In virtually every draft room, the elements were the same: a wall-sized big board with tiny names of hundreds of prospects; lots of brawny men in team polos (coaches) and less-brawny men in suits (executives), along with plenty of rolling desk chairs, stacks of thick binders, and cans of diet Coke.

The room where the Jets conducted their draft was an auditorium-style conference room with rows of long desktops. And on the first night of the 2018 draft, each row of desks was wrapped in signage for the $1 video vending machine Redbox.

Someone had to do it, I suppose. Let it be known that while the Jets may still be chasing their first playoff berth since 2010, they did become the first team to sell corporate signage on their draft-day desktops.

This is the National Football League in 2018.

For those who thought it was impossible for the league to be overexposed, Thursday Night Football has become the problematic test case, where the innate appeal of the NFL on TV faces its most obvious contradictions and complications. TNF is the stepchild of the league’s prime-time programming moves to Fox this season after splitting time between NBC and CBS (with the NFL Network simulcasting). It was both an unloved ratings disappointment in 2017 and also—because it’s the NFL—one of the five top-rated shows on TV.

Even passionate football fans are rarely passionate about the Thursday Night package. It seems like one piece of cake too many. The league already effectively shows three national games a week—the late-Sunday-afternoon doubleheader broadcast that goes out to most of the country on Fox or CBS, Sunday Night Football on NBC, and Monday Night Football on ESPN. It’s difficult to find a slate of consistently attractive matchups for a fourth national game.

We have a horrible relationship with the players.NFL executive

It was in 2012 that the Thursday Night schedule began running nearly every week of the season. By 2015, with players and fans alike grumbling about the quality of play, the league resorted, infamously, to Nike’s “color rush” uniforms. The concept’s debut, in the Bills-Jets game in 2015—Buffalo in red-on-red versus New York in green-on-green—wreaked havoc for color-blind viewers and looked like Christmas on acid to the rest of us. (If, a year earlier, you’d have seen such clashing, garish color schemes in a movie, you’d say the filmmakers didn’t know anything about pro football.)

But the dodgy uniforms are less important than the consensus among serious sports fans that the quality of the game suffers in these often tepid matchups. That’s an opinion shared by players, who straight-up hate the Thursday games, for the understandable reason that playing a football game on a Thursday after you’ve just played a football game on Sunday is ludicrous. Richard Sherman put it more bluntly in his Players’ Tribune column in 2016: “Thursday Night Football is just another example of the NFL’s hypocrisy: The league will continue a practice that diminishes the on-field product and endangers its players, but as long as the dollars keep rolling in, it couldn’t care less.” Ad Age’s NFL TV expert Anthony Crupi described it as “crummy, dangerous football.”

In the face of this pushback, Goodell has persistently suggested—and the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones reiterated last week—that the league’s regular season should expand to 18 games, often under the guise of reducing the number of preseason contests from four to two. Jones went so far as to argue that playing two more regular-season games at full-speed would be “safer,” the sort of statement that could be made only in a postfactual world.

As a volley into the marketplace of ideas, this is oblivious. The public isn’t clamoring for an 18-game regular season, and the players won’t go for it. With the league trying to reassure fans and players alike about the safety of this dangerous and at times brutal sport, the answer cannot be more games. A league that was aware of its self-image, or had connected its desire for player safety to the larger marketing of the game, would come up with a different solution.

What would make far more sense, if the NFL wanted to emphasize player safety and also better showcase its Thursday lineup, is to add a second bye week to each team’s 16-game schedule and stipulate that one of those byes fall before each team’s Thursday-night game. Then you would never have a team playing a game on three days’ rest, and the quality of the games themselves could only improve. For those preoccupied with monetization, this would also spread the 16-game schedule over 18 weekends, giving the NFL an extra week of programming “inventory”—i.e. games—to sell.

In his 2016 book But What If We’re Wrong: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past, Chuck Klosterman asked Malcolm Gladwell and me whether football would still be a culturally relevant enterprise in 100 years. Gladwell spoke with certitude that the game would perish within 25 years. (“This is a sport that is living in the past, that has no connection to the realities of the game right now and no connection to the rest of society.”) I argued that the game would survive by becoming significantly safer, just as it did in the early 1900s, when president Teddy Roosevelt attempted to reform the sport.

I don’t relish being on the opposite side of Gladwell in an argument and I share his alarm at much of the latest research on concussions among present players and the incidence of CTE and Alzheimer’s among former players. His dire prognosis could be right. But I’m still putting my money on the game’s durable popularity, as well as science, equipment, safety, and the fanatical devotion of football people to the game they love.

We like to laugh at the excesses of football types, because at times they can be monomaniacal and competitive to a fault. Early in the ’00s, when Jon Gruden was becoming famous for setting his alarm for 3:17 a.m., someone asked Brian Billick, then coaching the Ravens, what time he got up in the morning. “An hour before whenever Jon Gruden lies about waking up,” Billick said.

Football people are always the first to spring to the sport’s defense, but most of the people at the league and club levels recognize concussions and CTE as the league’s most crucial issue.

“I think it’s certainly the elephant in the room,” said one league executive. “And they’re alarmed by it. But it’s also true that we’ve been working to make things safer for decades. Everybody’s just paying more attention to it now.”

Safety was the clear priority in the Competition Committee’s rule changes for 2018. With no running starts for the kick coverage team and no wedges for the return team, kickoffs will be duller but also safer. The bigger rule change will penalize players who lead with the helmet when initiating contact. Officiating crews are struggling to interpret the rule correctly, and, over the course of the regular season, will penalize your own team far too often and other teams not nearly enough. There’s already grumbling about the new rule among football purists (“they’re fucking with the fabric,” said one fan I know).

One coach worried that if the league continues to make rule changes to try to make the game safer, a portion of its fan base will peel off to more unabashedly violent sports.

The league is always playing this eternal game of defense. Everything feels slow, defensive, reactive.NFL coach

That may be, but I also know people who are growing disenchanted partly because they feel the game is already too violent. My friend, the writer Joe Posnanski, is one of many former true believers who’s fallen out of love with pro football. (Being from Cleveland, Posnanski uncoupled himself from the NFL last year in the most painful way possible—watching only the 16 Browns games, all losses.) Others have stopped watching football as devotedly or, in some cases, entirely. You may run in different circles, but in my experience, this has less to do with protests during the national anthem than it does with an increasing ambivalence about the game and what it connotes, as well as the belief that the matchups are overlong, over-officiated, dangerously violent and, for all these reasons, not as much fun to watch.

And yet for all of the NFL’s missteps and challenges, pro football remains a nearly incomparable spectacle, eminently watchable both in person and at home. Competitiveness is at an all-time high, and the last two Super Bowls have been certifiable epics. With the exception of the annual bingo free space that the Patriots enjoy in the AFC East, every division has had multiple champions over the past three years.

It’s hard to come up with any sporting event in the near future that could plausibly challenge pro football’s popularity. The NBA is a wonderfully played, smartly marketed game, but even Game 7 of the Finals doesn’t approach the audience that the Super Bowl or a conference championship game enjoys. And nothing else is even close. Soccer in America, while growing, can’t begin to approach the gravity and long tradition of the NFL. Baseball’s audience, increasingly, is a homogenous, aging demographic.

At the end of America’s Game, Bill James makes an insightful point about baseball’s decline in popularity in the second half of the 20th century. “Baseball in 1960 was run by people who loved baseball,” he said, “but it was run by people who, because they loved baseball so much, assumed that there was something ‘special’ about baseball which had propelled it to its predominant position in the American sports world. And because they made this assumption, they allowed the game to drift. They didn’t really think about the game, as a commercial product.”

The NFL has had no qualms thinking about its game as a commercial product. But at times, the league’s greatest strength has also been a weakness.

In thinking business first, the people who run the NFL have it backward. The league’s salvation does not rest with the successful marketing of the desks in the New York Jets’ war room. Instead, the truth that existed for decades remains true today: The things that are good for the game of football—to make it safer, more watchable, more absorbing—will also, eventually, be good for the business of football.

Football will always be a dangerous sport. But it’s also a great game. The challenge for the people who are running the NFL is how to make it a safer sport while ensuring it remains a great game. In the process, the league has to find a better way to cut through its own clutter, make a case for itself, and try to get a new generation of people to fall in love with football.

“I don’t think we should be a business based on maximizing return on investment,” said one veteran executive. “We should be a business based on maximizing the enjoyment of the game, making it the best game it can be.”

Easier said than done. But if the NFL can accomplish that, it will continue to prosper as the biggest and most commercially reliable game on the American sports landscape.

If it fails, then its popularity will surely diminish and, at some point, the league will be reminded that its present position as America’s Game is only a fact, not a birthright.

Michael MacCambridge is the author of America’s Game: How Pro Football Captured a Nation and other books. He lives in Austin.